ABP has bought the 50% shareholding in Slaney Foods, as revealed by farmersjournal.ie. The deal is subject to approval by the relevant regulatory and competition authorities. The stake in Slaney was previously owned by the Allen family. The remaining 50% remains in the ownership of the Linden Food Group, which is majority controlled by the Co Armagh-based farmers co-op Fane Valley.

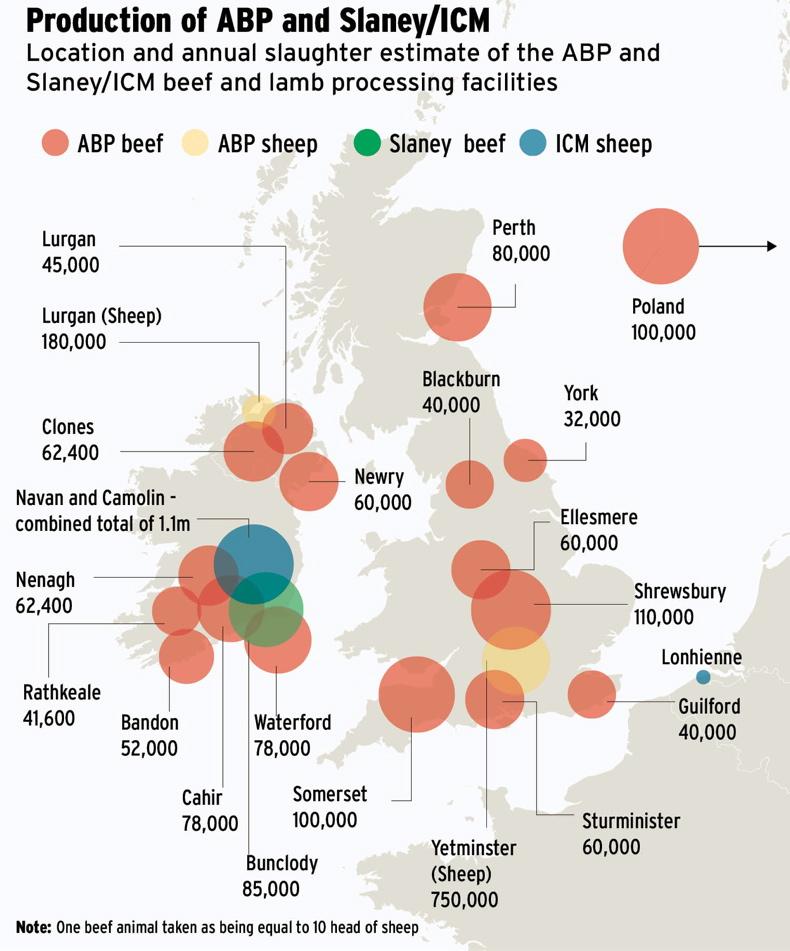

Slaney Foods has a cattle processing abattoir in Enniscorthy, Co Wexford, and lamb processing facilities in Navan, Co Meath, Bunclody, Co Wexford, and Bruges in Belgium.

The company was established by the Allen family at the Enniscorthy site in the early 1970s with lamb processing the main focus. In the era before Ireland joined the then EEC, the company benefited from the free trade agreement on lambs secured by the Irish Government with France.

Along with Dublin Meat Packers, the company shipped huge numbers to France, with the Rungis market in Paris the main destination. When Ireland joined the EEC in 1973, beef processing took off, with cattle bought, processed and stored in Intervention.

This was an EEC market support that bought beef when the market fell below a certain level and sold it when markets were stronger. There was also an Aid to Private Storage Scheme (APS), under which companies were financially supported to store product at times of peak cattle supply.

Linden Foods

The nature of the Slaney business remained similar up to the end of the century. However, after the McSharry CAP reforms of 1992 when the EU market support switched to direct payments to farmers and away from intervening in the beef market, the beef processing business also had to change. The beef export ban on the UK imposed in 1996 meant Northern Ireland companies could no longer service lucrative markets developed successfully in mainland Europe, foremost of which was the branded Greenfields beef into Albert Heijn in Holland. Linden Foods was among the leading beef exporters from Northern Ireland, with 70% of their total sales exported.

The company had lots of good business that it couldn’t supply due the export ban. A link-up with Slaney Meats, a company that was looking to develop commercial markets to replace the dwindling Intervention and APS business, made sense. This perfect fit meant Slaney could focus on servicing mainland European markets while Linden switched its focus to developing the UK market, with Marks & Spencer becoming its flagship customer alongside OSI, manufacturer of McDonald’s burgers.

Listen to a discussion of the ABP-Slaney deal in our podcast below:

The new north-south venture between Linden and Slaney acquired Irish Country Meats (ICM) lamb processing facilities in Navan and Camolin from Glanbia in 2000 and Slaney Meats rebranded as Slaney Foods. A further lamb processing, packing and distribution business, Lonhienne in, Liege, Belgium, was acquired in 2011. The individual businesses retained their identity within the umbrella Linden Food Group. Linden Foods continued in Northern Ireland, owned by Fane Valley with the Waugh family retaining a minority shareholding. Slaney Foods was owned 50:50 by Linden and the Allen family. Slaney Foods owned 92% of ICM and Lonhienne, with Joe Hyland the other 8%. The company invested heavily in upgrading its facilities over the past decade and is now considered to have among the best in the industry.

Reasons for sale

Slaney Foods has been a family-owned business, with the Allen family continuing to retain 50% ownership. Bert Allen has been the public face of the company for almost five decades, and the decision to retire from the meat business isn’t without logic. He is part of the generation that created the modern Irish meat processing industry but among the wider public his sons Bertram and Harry have a bigger profile thanks to their show jumping successes. They are German-based where Bert Allen is known to have considerable interests in renewable energy and property.

Surprising twist

While his decision to sell may not be that great a surprise, the customer is. Ordinarily we might expect that the Fane Valley co-op might, through Linden Food Group, acquire the Allen-owned share of the company. That it chose not to do so indicates that it is comfortable working with an outside company and a major competitor on both sides of the border.

This decision tells us much about the ongoing development of the meat processing industry and its markets. The original Linden-Slaney venture came about to exploit the then lucrative mainland European beef markets. However, in the past few years they have ceased being lucrative, with the British retail and fast food market being the main show in Europe. Slaney Foods no longer has the lucrative beef customers and, while Linden have Marks & Spencer, it doesn’t provide the volume that the major UK retailers do.

ABP, on the other hand, supplies the major UK-based retailers including the discounters, and has a global portfolio of customers that is among the best in the industry. Added to this is the company’s utilisation of offal and by-products, again considered among the best. Also, its recycling business interests have made ABP a carbon-neutral company. This knowledge and expertise combined with the excellent Slaney facilities create an opportunity that would have been difficult for Linden to exploit alone.

Linden choosing not to go solo also tells us much about the modern meat processing business and how difficult it is for a medium-sized company to prosper in this low-margin, high turnover industry. It also highlights how difficult it is to operate outside the UK retail business. A decade ago it was possible to work with a spread of French, Dutch and Italian customers as an alternative.

There is a sort of similarity with the UK motor industry and the example of Rover, a flagship company until it folded over a decade ago. It was described as too small to compete with the global giants yet too big to be a niche player. The Irish and UK meat industry is now dominated by large groups such as ABP, Dawn, Dunbia, Kepak, with Foyle and Liffey also acquiring multiple sites in recent years.

What each side brings

It is clear that the new joint venture is in many ways a second marriage of convenience. Originally it was Linden’s customer portfolio for beef that met the perfect match in Slaney’s production facilities. This time Linden needs its customer portfolio strengthened, which ABP will do in spades. The Slaney facilities are top notch and any potential supermarket customer will be impressed.

Then there is the sheep side of the business. Slaney Foods’ Irish Country Meats plants have long been regarded as being at the forefront of adding value to lambs in Ireland and have been one of the dominant players in the Irish market; and Lonhienne is the leading lamb processing business in Belgium. Also, ICM has a superb production and distribution network in Ireland, Britain and northern Europe for lamb. This is an area where ABP will gain from Slaney as while it has its own lamb businesses, beef is regarded as its dominant product.

Implications for Irish farmers

Concerns have been expressed by Irish farmer representatives about the loss of competition that consolidation brings.

Yet a factory at every crossroads doesn’t guarantee competition – it can in fact cause a depression of farmgate prices if a large factory isn’t operating to full capacity.

A strong consolidated processing sector has potential to deliver a better deal for farmers. The greatest curse of recent years has been price volatility, with the farmer buying stores to finish or selling weanlings at the mercy of where the market is on the day that he is buying and selling.

If processors are consolidated, they are in a stronger position to negotiate with the major British retailers and less likely to be attacked at the selling end by independent companies looking to undercut them.

If processor power is properly used, it can create more market stability. The problem is lack of farmer confidence in meat factories doing business with them and this confidence is something processors have to earn.

What will happen next?

It will be interesting to see if the Linden-ABP marriage is a long-term mutually beneficial relationship like the previous one was for the past 15 years. Linden has demonstrated its ability to operate a partnership and ABP has also built strategic alliances with external partners. Yet there is a nagging question – will ABP want to take the Linden share of the business as well at some point?

There is also the question of the future direction of meat processing. Since the horsemeat incident, product integrity has become paramount in the industry. At the time, blue chip plc retailers and food companies were badly exposed by how little they knew about the supply chain of their meat offerings. Much work has been done since to put that right and retailers are now favouring more integrated processing businesses. The Slaney-ABP venture will reduce ABP’s need to source outside its own companies, and it is easy to visualise further mergers and acquisitions.

Even the large groups aren’t beyond being targeted by the major global players. Earlier this year, JBS, the world’s biggest meat processor, acquired the Moy Park poultry business in Northern Ireland in a €1.3bn deal. Until this its European presence was restricted to a single beef business in Italy. JBS has several businesses in the Americas and has been on the acquisition train for several years now, spending over €6bn. With talk of global trade deals with the US and Mercosur countries in the offing, don’t be shocked if some of the larger groups are targeted as well.

SHARING OPTIONS