LOYALTY CODE:

The paper code cannot be redeemed when browsing in private/incognito mode. Please go to a normal browser window and enter the code there

LOYALTY CODE:

The paper code cannot be redeemed when browsing in private/incognito mode. Please go to a normal browser window and enter the code there

This content is copyright protected!

However, if you would like to share the information in this article, you may use the headline, summary and link below:

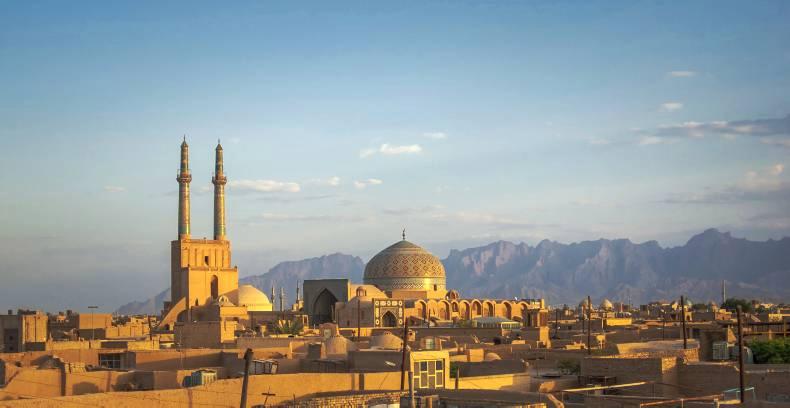

Title: Iran - the land of opportunity?

The lifting of international sanctions on Iran paves the way for Irish food exporters to explore opportunities, but challenges remain. Eoin Lowry reports from the Middle East

https://www.farmersjournal.ie/iran-the-land-of-opportunity-207474

ENTER YOUR LOYALTY CODE:

The reader loyalty code gives you full access to the site from when you enter it until the following Wednesday at 9pm. Find your unique code on the back page of Irish Country Living every week.

CODE ACCEPTED

You have full access to farmersjournal.ie on this browser until 9pm next Wednesday. Thank you for buying the paper and using the code.

CODE NOT VALID

Please try again or contact us.

For assistance, call 01 4199525

or email subs@farmersjournal.ie

Sign in

Incorrect details

Please try again or reset password

If would like to speak to a member of

our team, please call us on 01-4199525

Reset

password

Please enter your email address and we

will send you a link to reset your password

If would like to speak to a member of

our team, please call us on 01-4199525

Link sent to

your email

address

![]()

We have sent an email to your address.

Please click on the link in this email to reset

your password. If you can't find it in your inbox,

please check your spam folder. If you can't

find the email, please call us on 01-4199525.

![]()

Email address

not recognised

There is no subscription associated with this email

address. To read our subscriber-only content.

please subscribe or use the reader loyalty code.

If would like to speak to a member of

our team, please call us on 01-4199525

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

Update Success !

Following decades of political and economic disruption, Iran is reasserting its position in the world, strengthening its trade with exporters like Ireland.

As the second-largest economy in the Middle East, with a population of 80m people, the recent lifting of sanctions should offer opportunities for Irish dairy processors. Last year, Irish food and drinks exports to Iran reached €3.6m.

But we must not be fooled by the large population; Iran is not an easy place to do business. The World Bank ranks it at 130 in its ease of doing business ranking compared to the UAE at 22.

As the economy grows and demand for premium food products outstrips domestic supply, Iran is looking to countries like Ireland to supply high quality, safe and sustainably produced food.

More than 100 Iranian food buyers met Irish food companies including dairy processors last week on a trade mission to Iran, organised by Bord Bia and the Department of Agriculture. Interestingly, Ireland at one stage exported almost 120,000t of beef annually to Iran, almost a fifth of our annual beef production.

Ireland therefore has strong historic trading relationships with Iran, but because of political tensions with the UN and the United States, trade with the EU and therefore Ireland was effectively reduced to zero in recent years. Now with the relaxation of UN and EU sanctions, it is hoped that trade will open up again.

Iran is an interesting economy. While it is a large producer of oil, unlike other oil countries in the Gulf, such as Saudi Arabia, it has a real economy outside of oil.

Even though it is a member of OPEC, it was unable to sell its oil to many countries in recent years. It therefore had to sell its oil at a discount to a small number of countries so was relatively insulated from the collapse of oil prices.

Its economy is expected to grow over the coming years, as trade opens up and it can trade oil in more international markets.

With a well-educated population and 40% under the age of 25 along with an economy anticipated to expand 2% annually in the coming years, the lifting of sanctions can only drive trade and the economy even more.

BSE has often been blamed for the elimination of Irish beef exports to Iran. However this is not entirely true and was mainly down to Irish beef becoming uncompetitive due to the elimination of export refunds along with cheap beef arriving from Brazil more than a decade or so ago.

In fact today, 190,000t of beef comes from Brazil. Therefore as other international markets are offering better returns for Irish beef, the focus and opportunity for Ireland is in dairy exports.

Some of the dairy companies taking part on this trade mission included Arrabawn, Carbery, Dairygold, Glanbia, Kerry Group, Lakeland, LacPatrick, and Ornua.

Iran has for millennia had its roots firmly planted in farming. Over 2,000 years ago, this was the first place in the world to have a settlement similar to a farm.

This is a country with 10 times the agricultural land of Ireland, more than 10 times our population, yet imports 7.5m tonnes of feed to produce its milk.

It’s milk pool is 8bn litres, compared with our 6bn litres and expected to reach 14bn litres by 2025.

Inside an Iranian dairy farm

Iranian farms are for the most part privately owned and organised into regional co-ops. Annual supply contracts are usually agreed with processors and milk is delivered daily. Almost half of the dairy farms have more than 200 cows.

Ahmad Espinas runs Tehrah Laban dairy farm, which was established in 1977 and much like the cars on the roads, has not changed much since. Asking him what he expects milk price to be this year, he tells me that it depends on what the government decides, as it heavily subsidises milk and right now he recieves 41c/litre for his milk.

He is running one of the largest dairy farms in Iran, milking 2,600 cows three times a day. The mainly Holstein herd is housed indoors and fed imported alfalfa and maize from South America. The farm has seen minimal investment over the last 40 years, running the same 50-unit parlour it installed in the 1980s.

Annual milk yields are 9,000 litres per cow, and after three lactations cows are culled. The average fat content is 3.35%, with average protein content sitting at 3.11% – low compared with Irish standards, a direct result of not paying on protein.

One hundred and eighty people work on the farm with old but fit for purpose machinery.

Many say that Iran was always modern. But just spending a few days here begs the question – was it more modern in the past than it is today? Judging by this farm, it would appear that is the case.

Inside an Iranian dairy processor

Iran Dairy Industries was established in 1958 and is the largest dairy company in the Middle East, processing 1.2bn litres per annum. This makes it similar in size to Dairygold. It has 30% of the market, with a range of over 600 consumer products.

Speaking with Dr. Ahmad Jayram managing director, he says his company has benefited from the ban on western products in Russia. Despite the investment in up-to-date modern packing facilities, the company employs 8,000 people, with over 900 in production on their main site.

According to Farid Taymouri from the Dairy Association of Iran, Iranians consume 3.5m tonnes of dairy products ever year. He says this is growing at a rate of 4% per annum, or 140,000t per year. They certainly like their milk, consuming 160kg per head every year and forecast to grow by 50% by 2025. Last year the country spent US$7bn on dairy products.

Although raw milk price is set by the government, the market price is set by supply and demand. While 10 companies control 75% of dairy processing, five brands hold 50% of the market.

Liquid milk is by far the largest category in the dairy aisles, accounting for 25% of the market, followed by UHT (13%) and Cheese (10%). Dough, a traditional flavoured yogurt drink, accounts for 12%, cream 4% and butter a very small 0.5%.

Born out of a need to historically make rather than import its finished food products, Iran has a burgeoning food manufacturing sector, that uses 230,000t of dairy ingredients. After, all this is country that has been shut off for the most part from the rest of world due to sanctions imposed originally in 1979 and in various forms ever since.

The array of food products available in supermarkets today is impressive. While not familiar brands they are similar to anything on offer in Europe.

One hundred and eighty thousand tonnes of cheese is used in food manufacturing, along with 40,000t of butter and around 10,000t of dairy powders. Butter as an ingredient is expected to grow 10% per annum over the next 5 years.

Iran uses all the cream from its milk to make cream cheeses. However this creates the problem where it has no cream to make butter. It therefore, imports butter mainly from New Zealand, Australia and Europe.

Financial sanctions

One of the key challenges of exporting to Iran has been the imposition of sanctions. With the lifting of some of these it should ease trade. However, while sanctions have been in place in many cases since 1979, they did not directly relate to food imports. In effect, they were financial sanctions that made it difficult for Irish food exporters to receive payment for goods shipped. The Iranian banking system is a little chaotic, with many international banks not wanting to be seen to facilitate trade at the expense of other nations’ financial business. Their policies may loosen in the near future.

Fragmented retail sector

The retail sector is fragmented, with independent small grocers by far dominating the grocery retail channel. Modern supermarkets such as those in Ireland account for less than 1% of the grocery market, but this is changing rapidly. In the supermarket, a litre of milk costs 60c/litre, with a litre of UHT milk as low as 25c/l.

Distribution

Given that much of the country’s population lives a long way from the main milk producing regions in the north, improving the milk collection infrastructure has been one of the key issues facing the industry.

In summary, there appears to be a real and immediate opportunity to supply dairy ingredient powders and as butter imports are expected to double by 2020 there is a real opportunity to supply butter into this unique country.

As some of the big brand names, including Nestlé are already present, building a brand is not going to be easy. However with first mover advantage, it may be possible.

The sustainability of their dairy chain has to be questioned. It is the polar opposite of Ireland. It will have to come under pressure on environmental and carbon footprint grounds into the future. It is only when you travel do you really see the unique and sustainable production system Ireland has to offer.

While high, the factory standards within Iran are at a much different level to Ireland. The fact that Russian authorities were happy to approve Iranian dairy processors ahead of Irish sites begs the question – do Russians approve on political grounds rather that on food safety and quality agendas?

SHARING OPTIONS: