Danish dairy farmers are technically among the best in the world. They have the highest milk yields per cow in Europe, at just over 10,000kg per cow, along with the largest average farm size in Europe at 154 cows per farm.

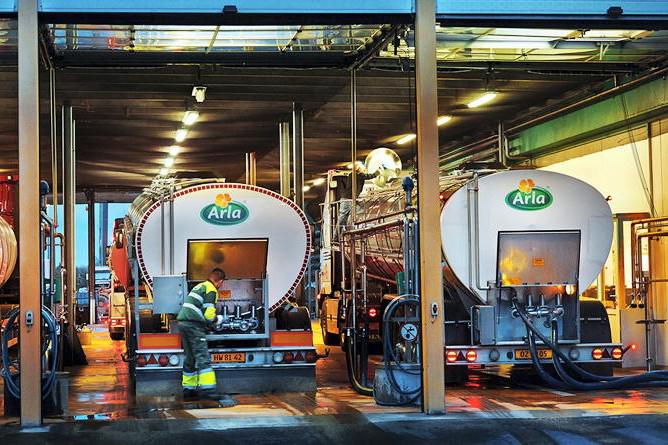

They have a good dairy breeding programme, being one of the first countries in the world to recognise the importance of health and fertility in dairy breeding. They also have a good farmer-owned independent advisory service and Arla as the co-operatively owned milk processor which has strong brands and a global footprint.

Despite all of these positives, Danish dairy farmers are struggling. Most of the 3,000 or so dairy farmers there are under considerable financial pressure. For some of these farmers, the recent increases in milk prices will come too late and 2016 will be the last year they will milk cows.

The Irish Farmers Journal travelled to Denmark to get a sense of the scale of the issue, and its source.

High costs

Denmark is a high-cost country in which to produce milk. The winters are long and cold, so the grass-growing season only lasts about seven months.

The vast majority of farmers have abandoned grazing altogether and have their cows housed full-time, feeding them grass and maize silage and lots of meal. Up to half of the diet could be concentrates and oftentimes this is from grain grown on the farm.

As a well-developed economy in northern Europe, living expenses and labour costs are high. A general farm operative can expect to earn about €18/hour, while a farm manager can expect to earn over €25/hour.

So the cost of producing milk in Denmark is high. However, generally speaking, technical performance is good and while the system of milk production is high-input, it is also high-output.

Like Ireland, Denmark is a food exporting nation, so farmers are paid on fat and protein. Average milk solids production per cow is 740kg over a 305-day lactation.

The biggest issue is the debt level. Along with everything else, the Danes are the most indebted farmers in Europe, with average debt levels of €20,000 per cow, which is about €3.1m of debt per farm. In comparison, the average debt level on Irish dairy farms is less than €90,000.

High-cost production systems, combined with high debt levels, are crippling Danish farmers. Like in Ireland, Danish farmers are exposed to the world market and milk price volatility.

Milk price was at its lowest in June and July this year at 25c/l. It is now back up to 32.2c/l, based on protein of 3.4% and fat of 4.2%. Milk price in Denmark peaked in 2014 at 42c/l.

The situation on the ground is perilous. The milk price is failing to cover the cost of production and debt levels are rising further.

34c/l breakeven

A respected adviser I spoke to said, the average farmer needs a milk price of 34c/l to break even, while the very top farmers need a milk price of 28c/l to break even. These figures include own labour, interest and depreciation, but not capital repayments.

With such a high breakeven price, one wonders how Danish farmers managed to secure any credit, let alone multi-million euro loans to buy farms, expand existing farms and in the process build the best of infrastructure and install the most up-to-date technology and machinery.

The reality is that the credit bubble, under which Danish farmers have been operating for decades, has come to an end. The system of where debt is serviced by the current generation and added to and passed on to the next generation of farmers hasn’t served the industry well.

The system was built on the presumption of land prices continuously increasing in value. The current realignment is causing considerable hardship.

According to the adviser, the big winners were farmers who retired up to 2011. They got the full benefit of the massive increase in land prices that occurred up to then.

When they sold their farms, they became millionaires because their farms were worth much more than their debt. Many now drive top-end cars and some even bought small farms in other countries to move their tax liabilities to different jurisdictions.

But now that land prices have almost halved from their peak of €19,000/acre to €7,000/acre today, most farmers are in severe negative equity.

Farmers in Denmark can borrow money in two ways. Up to 60% of the market value of land and fixed assets (buildings) can be borrowed from a credit union or building society-type lender. These are long-term loans offered at very low interest rates (0%), plus an annual administration fee of between 1% and 3%.

But these low-cost loans will only lend up to 60% of the market value. The rest of the money needed to buy land or build a new shed comes from conventional banks, with interest rates ranging from 4% to 8% (some farmers behind in payments are paying up to 12% interest).

Because the value of land has fallen, the banks no longer have security over their debt and, because milk prices have fallen, farmers cannot afford to pay back the loans. Most banks have already written off a large proportion of the farm debt on their own loan books.

Debt writedowns are also a feature at farm level. The farmers in the top left category of Figure 1 are most exposed. They have debt levels and their technical performance is on the lower end of the scale, meaning their costs of production are higher. They are a problem to the banks because they are unlikely to ever be able to pay back their debts.

Alongside operating on borrowed money, these farmers are also operating on borrowed time. The sad reality is that the banks are operating many of these farms.

Anecdotally, they are employing some of their good clients, or their sons and daughters, to oversee and run these farms and then offering them the option to buy the farm at current market prices, writing off a high proportion of the existing debt.

These sort of under-the-counter deals are enabled by the fact that some of the credit unions or building societies are also owned by the banks. Actual bankruptcy figures are still relatively low at just under 2%.

The carrot for the farmer taking on the new farm is that, in some cases, the new debt is capped at the level of the credit union debt, which is at a very low interest rate. However, they are still taking on large borrowings and these farmers need to be really efficient to make it work.

There are no winners from the Danish system. The banks are heavily exposed and have lost money. Some farmers are losing their farms. Where deals are being done with the banks they are avoiding the ignominy of the bankruptcy courts. Younger farmers are taking on more debt and risk.

So what are the lessons for Irish farmers? For me, you can be a high-cost farmer or you can be a farmer with high debts but you cannot be the two together. We see this is Denmark and New Zealand, two countries with traditionally high debt levels. Successful farmers there have managed to keep on top of their debt by running low-cost farms.

We see the same in Ireland. For some farmers, running low-cost operations isn’t a lifestyle choice, it’s a necessity because if they have expanded or bought land they have debt to repay. Of course, the sweet spot is to be low cost and low debt – this is where more Irish farmers should aim to be because they will best withstand the fluctuations of global milk price. Despite the negativity, Danish farmers have shown resilience in the past and with Arla’s support many will pull through the current crisis

SHARING OPTIONS