The warning from Brussels this week that member states need to step up preparations for a no-deal Brexit is the most honest assessment to date as to the extent to which the negotiations between the EU and Britain have failed to reach agreement on the key issues.

With the end of the road down which the can has been kicked now on the horizon, the rhetoric we have listened to of the past 18 months is now being replaced by reality: the reality that a withdrawal agreement, due to be concluded by October, is becoming less certain.

Without such an agreement, the UK would simply crash out of the EU next March, resulting in a hardest of hard Brexits. There are a litany of reports and assessments showing the severe economic impact this would have on the Irish economy and our agricultural sector in particular.

Perhaps the clearest example of how our exposure to a hard Brexit is over-amplified compared to the rest of the EU is that Ireland – a member state with less than 1% of the EU population – would be exposed to almost 20% of all WTO tariffs imposed on future EU trade with the UK.

Based on these figures, the warnings coming from Brussels this week to prepare for a hard Brexit are effectively telling farmers to prepare for a disaster scenario.

The warnings coming from Brussels to prepare for a hard Brexit are effectively telling farmers to prepare for a disaster scenario

The Government is likely to downplay the significance of the warnings from Brussels and the risk of the UK crashing out of the EU next March. However, in May, An Taoiseach Leo Varadkar was clear that unless there was meaningful progress in negotiations ahead of the EU leaders’ summit in June, particularly in relation to a backstop agreement on the border, it was difficult to see how any agreement would be reached by the October deadline.

With the leaders’ summit taking place next week, there is widespread acceptance on both sides that negotiations have effectively stalled in recent months with the British focused on internal political negotiations rather negotiations with the EU.

There is no doubt that negotiations will continue after next week’s summit concludes and that there is a long tradition of the EU coming back from the brink and reaching an agreement at the 11th hour. However, this should be of little comfort to the Government. At a special Brexit conference organised by the IIEA recently, former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern warned of the risks to Ireland of last-minute negotiations – painting a scenario where in order to get a deal over the line, Leo Varadkar would be forced into an early morning compromise by political heavyweights such as France and Germany. In such a scenario, it is easy to see how bargaining chips such as corporation tax could come on to the table in forcing Ireland to accept a Brexit compromise deal that does little to protect Irish interests.

Michel Barnier, Leo Varadkar and Simon Coveney.

Regardless of how negotiations play out over the next four months, we now know that a hard Brexit, which would devastate Irish agriculture, is becoming increasingly likely. It is therefore not acceptable for the Government or EU to effectively leave our largest indigenous sector – accounting for 10% of national employment – exposed to the whims of a UK government that is clearly in disarray.

Given the risks, it is time for the Government and the various organisations representing both the agri-food sector and farmers to turn up the political heat. The stakes are simply too high to continue to hope for the best. IFA president Joe Healy has correctly identified Brexit as one of the biggest threats to our industry in over a generation, yet our political response has been extremely measured when we compare it to how farmers took to the streets of Dublin to turn up the political pressure needed to protect Irish interests in global trade negotiations, including WTO, Mercosur and GATT.

The impact a hard Brexit would have on Irish agriculture far exceeds the combined impact of all of the above. It is clearly time for the sector to respond accordingly to ensure the EU puts in the necessary safety net to ensure the livelihoods of Irish farmers and those employed in the agri-food sector are protected.

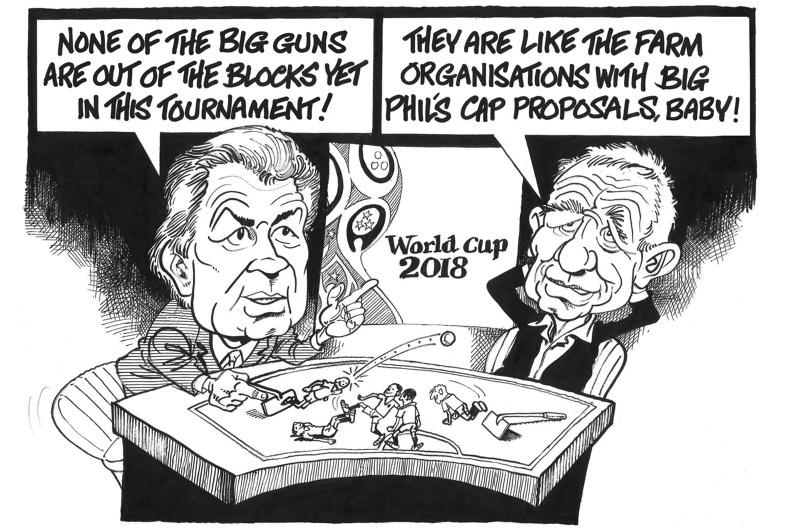

With European Commission President Jean Claude Junker, Commissioner Phil Hogan and chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier all in Dublin today (Thursday), there is an opportunity for them to allay the fears of Irish farmers by outlining plan B on Brexit. In the absence of plan B, farmers and the wider industry need to quickly reconsider how they can turn up the pressure to secure the necessary safeguards.

Grassland: managing grassland the key to realising a farm’s potential

The advantages that Irish grassland production provides – whether for meat or milk – were presented clearly and concisely at a well organised European Grassland Federation congress in Cork this week.

Yes, Irish farmers – particularly in the east – are experiencing the extremes of grassland management this year with snow covering farms in March while this week parts of Wexford and the east are heading for six weeks of no rain.

Many farmers are having to feed first-cut silage only ensiled a number of weeks ago. These are exactly the challenges of a grazing system as you simply cannot reduce all the variations and risks.

On a wider view, it is clear the area under grassland is decreasing in Europe as the trend of increasing intensification on a reduced, more urbanised area continues. Some work displayed in Cork shows that the area under permanent grassland has reduced on average by 11% across five of the major European countries – Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany and the Netherlands – between 1970 and 2013. That is hugely significant and shows how our grass-based systems could and will become more valuable and unique.

Climate change and predicted changes in grazing season length are often used by those selling intensive systems against grazing systems. However, the statistics show for the last 100 years (1900 to 2000), the average difference in temperature was only plus 0.4 of a degree Celsius. That allowed the researchers in Cork this week to predict that by 2070 there will be little or no discernible difference in grazing season length.

In terms of efficiency of the grass-based meat and milk systems, often the monogastric (pigs and poultry) are seen to be more efficient. The most recent research shows that to produce 1kg of boneless meat required 2.8kg of human-edible feed in ruminants systems and 3.3kg in monogastric systems.

With this piece of information, it is clear grass-based systems of ruminant production can play a significant role in meeting the increasing global demand for food by converting non-human-edible forages into high-quality human-edible protein.

For farmers, the key message is to stay ahead of the curve on technology and use the best grass and animal genetics to manage the land area available to them.

BEEF 2018: Teagasc to showcase its latest beef research at Grange

Teagasc's beef open day takes place every two years and has become a key event for those involved in the sector.

Next Tuesday 26 June, Beef 2018 takes place in Teagasc Grange. It should be an important event in the calendar of all those involved in the sector.

Our special Focus supplement this week details what will be covered over the course of the day. The biennial event gives Teagasc the opportunity to present to farmers and industry stakeholders the latest findings from beef research that has taken place at the Grange facility over the past two years. Given the challenges facing the beef sector, it has never been more important to ensure that facilities such as Teagasc Grange are driving forward the research agenda and continually presenting new technologies that can help farmers become more efficient.

We are in the fortunate position that, through Government support, our industry continues to have access to independent research.

Read more

What’s new at Teagasc BEEF 2018

The warning from Brussels this week that member states need to step up preparations for a no-deal Brexit is the most honest assessment to date as to the extent to which the negotiations between the EU and Britain have failed to reach agreement on the key issues.

With the end of the road down which the can has been kicked now on the horizon, the rhetoric we have listened to of the past 18 months is now being replaced by reality: the reality that a withdrawal agreement, due to be concluded by October, is becoming less certain.

Without such an agreement, the UK would simply crash out of the EU next March, resulting in a hardest of hard Brexits. There are a litany of reports and assessments showing the severe economic impact this would have on the Irish economy and our agricultural sector in particular.

Perhaps the clearest example of how our exposure to a hard Brexit is over-amplified compared to the rest of the EU is that Ireland – a member state with less than 1% of the EU population – would be exposed to almost 20% of all WTO tariffs imposed on future EU trade with the UK.

Based on these figures, the warnings coming from Brussels this week to prepare for a hard Brexit are effectively telling farmers to prepare for a disaster scenario.

The warnings coming from Brussels to prepare for a hard Brexit are effectively telling farmers to prepare for a disaster scenario

The Government is likely to downplay the significance of the warnings from Brussels and the risk of the UK crashing out of the EU next March. However, in May, An Taoiseach Leo Varadkar was clear that unless there was meaningful progress in negotiations ahead of the EU leaders’ summit in June, particularly in relation to a backstop agreement on the border, it was difficult to see how any agreement would be reached by the October deadline.

With the leaders’ summit taking place next week, there is widespread acceptance on both sides that negotiations have effectively stalled in recent months with the British focused on internal political negotiations rather negotiations with the EU.

There is no doubt that negotiations will continue after next week’s summit concludes and that there is a long tradition of the EU coming back from the brink and reaching an agreement at the 11th hour. However, this should be of little comfort to the Government. At a special Brexit conference organised by the IIEA recently, former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern warned of the risks to Ireland of last-minute negotiations – painting a scenario where in order to get a deal over the line, Leo Varadkar would be forced into an early morning compromise by political heavyweights such as France and Germany. In such a scenario, it is easy to see how bargaining chips such as corporation tax could come on to the table in forcing Ireland to accept a Brexit compromise deal that does little to protect Irish interests.

Michel Barnier, Leo Varadkar and Simon Coveney.

Regardless of how negotiations play out over the next four months, we now know that a hard Brexit, which would devastate Irish agriculture, is becoming increasingly likely. It is therefore not acceptable for the Government or EU to effectively leave our largest indigenous sector – accounting for 10% of national employment – exposed to the whims of a UK government that is clearly in disarray.

Given the risks, it is time for the Government and the various organisations representing both the agri-food sector and farmers to turn up the political heat. The stakes are simply too high to continue to hope for the best. IFA president Joe Healy has correctly identified Brexit as one of the biggest threats to our industry in over a generation, yet our political response has been extremely measured when we compare it to how farmers took to the streets of Dublin to turn up the political pressure needed to protect Irish interests in global trade negotiations, including WTO, Mercosur and GATT.

The impact a hard Brexit would have on Irish agriculture far exceeds the combined impact of all of the above. It is clearly time for the sector to respond accordingly to ensure the EU puts in the necessary safety net to ensure the livelihoods of Irish farmers and those employed in the agri-food sector are protected.

With European Commission President Jean Claude Junker, Commissioner Phil Hogan and chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier all in Dublin today (Thursday), there is an opportunity for them to allay the fears of Irish farmers by outlining plan B on Brexit. In the absence of plan B, farmers and the wider industry need to quickly reconsider how they can turn up the pressure to secure the necessary safeguards.

Grassland: managing grassland the key to realising a farm’s potential

The advantages that Irish grassland production provides – whether for meat or milk – were presented clearly and concisely at a well organised European Grassland Federation congress in Cork this week.

Yes, Irish farmers – particularly in the east – are experiencing the extremes of grassland management this year with snow covering farms in March while this week parts of Wexford and the east are heading for six weeks of no rain.

Many farmers are having to feed first-cut silage only ensiled a number of weeks ago. These are exactly the challenges of a grazing system as you simply cannot reduce all the variations and risks.

On a wider view, it is clear the area under grassland is decreasing in Europe as the trend of increasing intensification on a reduced, more urbanised area continues. Some work displayed in Cork shows that the area under permanent grassland has reduced on average by 11% across five of the major European countries – Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany and the Netherlands – between 1970 and 2013. That is hugely significant and shows how our grass-based systems could and will become more valuable and unique.

Climate change and predicted changes in grazing season length are often used by those selling intensive systems against grazing systems. However, the statistics show for the last 100 years (1900 to 2000), the average difference in temperature was only plus 0.4 of a degree Celsius. That allowed the researchers in Cork this week to predict that by 2070 there will be little or no discernible difference in grazing season length.

In terms of efficiency of the grass-based meat and milk systems, often the monogastric (pigs and poultry) are seen to be more efficient. The most recent research shows that to produce 1kg of boneless meat required 2.8kg of human-edible feed in ruminants systems and 3.3kg in monogastric systems.

With this piece of information, it is clear grass-based systems of ruminant production can play a significant role in meeting the increasing global demand for food by converting non-human-edible forages into high-quality human-edible protein.

For farmers, the key message is to stay ahead of the curve on technology and use the best grass and animal genetics to manage the land area available to them.

BEEF 2018: Teagasc to showcase its latest beef research at Grange

Teagasc's beef open day takes place every two years and has become a key event for those involved in the sector.

Next Tuesday 26 June, Beef 2018 takes place in Teagasc Grange. It should be an important event in the calendar of all those involved in the sector.

Our special Focus supplement this week details what will be covered over the course of the day. The biennial event gives Teagasc the opportunity to present to farmers and industry stakeholders the latest findings from beef research that has taken place at the Grange facility over the past two years. Given the challenges facing the beef sector, it has never been more important to ensure that facilities such as Teagasc Grange are driving forward the research agenda and continually presenting new technologies that can help farmers become more efficient.

We are in the fortunate position that, through Government support, our industry continues to have access to independent research.

Read more

What’s new at Teagasc BEEF 2018

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: