Leading global consultancy firm McKinsey has published a Reducing agriculture emissions through improved farming practices report.

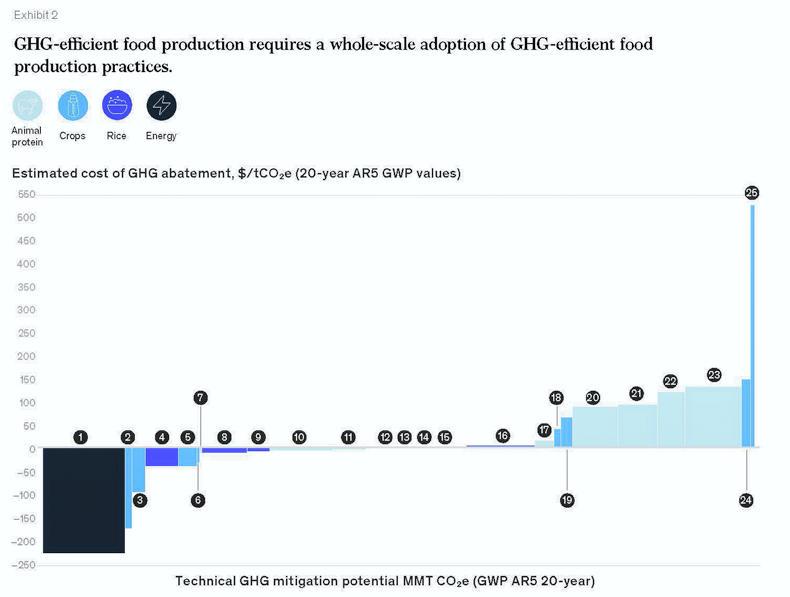

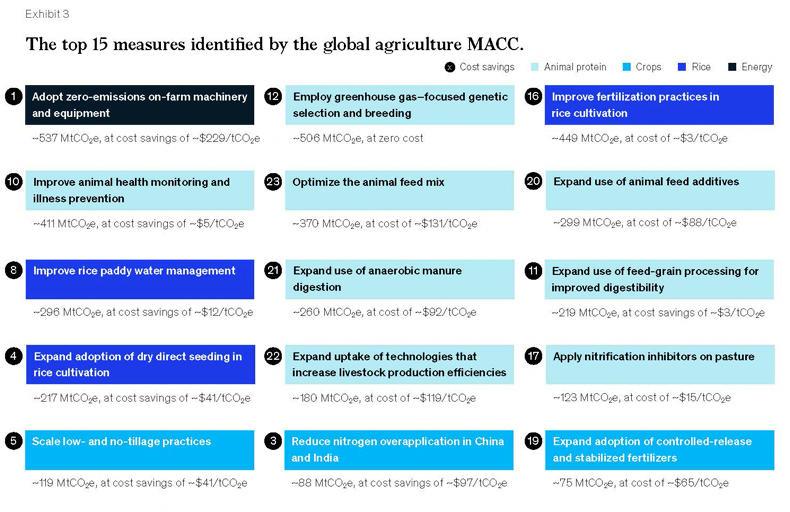

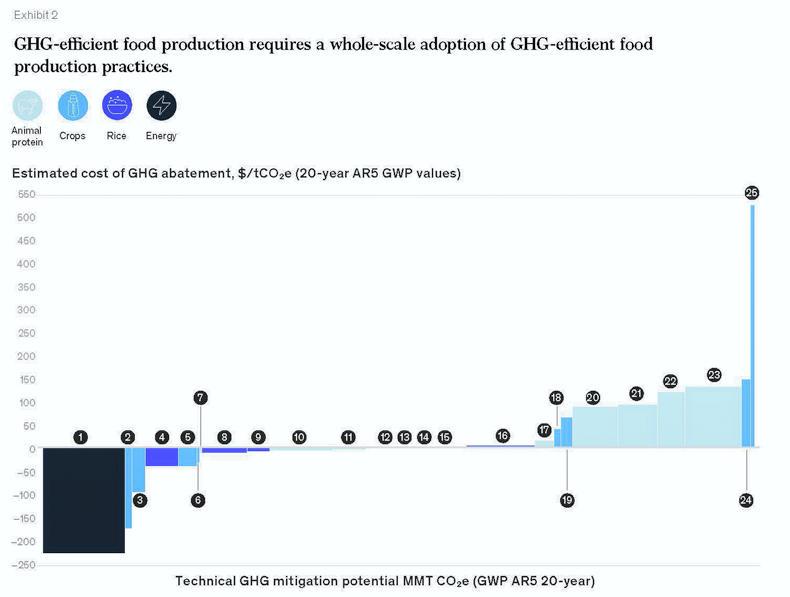

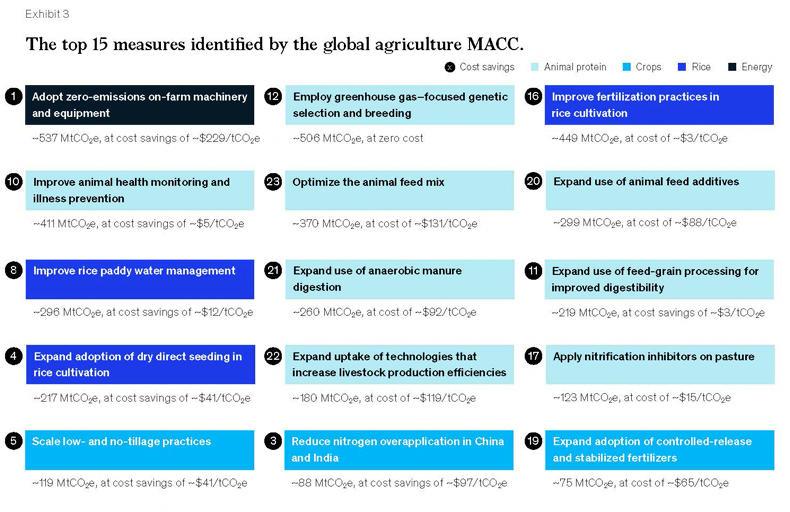

It says it has used a decade of analysis of GHG abatement to identify the top 25 measures to reduce on-farm emissions and organised them into a marginal abatement cost curve (MACC).

It claims these measures have the potential to achieve a reduction of 20% of emissions from agriculture, forestry and land use change.

Fifteen of the changes identified are cost-neutral, with the biggest potential for reduction emissions coming from having farm machinery and equipment with zero emissions. Also, the top 15 changes deliver 80% of the gains.

Global variation

As it is working on a global basis, McKinsey recognises that its use of average values won’t reflect global variations. It also presents the study against the background of a global population in 2050 that will have an increased per-capita food demand between 8% and 12%.

With the growing global demand for food into the future and even with the adoption of best practices, emissions from agriculture are considered extremely high.

The report recognises the difficulty of developing best practice in a sector where two billion people are involved and where one-third of global food production is on farms of 2ha or less.

These farms account for three-quarters of all farms in the world and given their number makes global policy change difficult.

Behavioural change

The report identifies the difficulties with changing production to achieve a further decrease in emissions and goes on to look at lifestyle issues.

It highlights that one-third of all food produced, and having incurred the emissions in doing so, is wasted. A severe cut in food waste is an obvious staring point in the issue with emissions from agriculture and food.

The other point that will be controversial with farmers is the identification of ruminant livestock (cattle and sheep) as the main perpetrators in farming.

It recommends a switch to poultry and pigmeat as alternative proteins to beef and lamb, given that their emissions are estimated by the report using the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (UNFAO) data.

It shows that beef, including dairy cows, generates 46.2kg CO2e/kg of protein, lamb 35.8kg CO2e/kg of protein, pigmeat 5.8kg CO2e/kg of protein and poultry is 5.2kg CO2e/kg of protein.

The report suggests that beef and lamb per-capita consumption should be halved. Interestingly, dairy has a very low 2.8kg CO2e/kg of protein - this is because the role of the cow in dairy production is accounted for in the beef category.

There is nothing particularly new in the McKinsey report, although such is their standing globally with governments and international organisations that they are key influencers of decision-makers.

Proteins such as pigmeat and poultry are in the ascendancy anyway for commercial reasons more than emissions content in satisfying the global demand for protein.

Beef and lamb are more expensive, luxury products and increasing demand for these is from developing countries that consume more as the wealth of their citizens increases.

Nowhere demonstrated this more than China, which imported negligible quantities of beef in the first decade of this century to becoming the biggest importer in the world during the second decade.

Beef, and to a lesser extent lamb, has endured an extremely negative press for several years, yet the global demand continues to grow, even if it is static in Europe and the USA.

There is going to be a global demand for beef, so it is a case of meeting that demand in the way that does least damage to the environment.

This is achieved by targeting production to areas of the world that have tracts of marginal grassland, unsuitable for other productive agriculture and immediate access to water.

That means beef and lamb production to service global demand should be encouraged in the marginal lands of Ireland, Britain, western France, Belgium and northwestern Spain, plus areas of Scandinavia and the Netherlands.

Grassland areas with water supply in North and South America, New Zealand and some parts of Australia are also suitable.

What isn’t sensible is deep-well irrigation and import of concentrated feed into arid areas of the world to produce livestock.

Read more

Colm McCarthy: common sense needed

Environmental opportunity for NI agriculture

Fossil fuels v agriculture emissions - a skewed debate

Leading global consultancy firm McKinsey has published a Reducing agriculture emissions through improved farming practices report.

It says it has used a decade of analysis of GHG abatement to identify the top 25 measures to reduce on-farm emissions and organised them into a marginal abatement cost curve (MACC).

It claims these measures have the potential to achieve a reduction of 20% of emissions from agriculture, forestry and land use change.

Fifteen of the changes identified are cost-neutral, with the biggest potential for reduction emissions coming from having farm machinery and equipment with zero emissions. Also, the top 15 changes deliver 80% of the gains.

Global variation

As it is working on a global basis, McKinsey recognises that its use of average values won’t reflect global variations. It also presents the study against the background of a global population in 2050 that will have an increased per-capita food demand between 8% and 12%.

With the growing global demand for food into the future and even with the adoption of best practices, emissions from agriculture are considered extremely high.

The report recognises the difficulty of developing best practice in a sector where two billion people are involved and where one-third of global food production is on farms of 2ha or less.

These farms account for three-quarters of all farms in the world and given their number makes global policy change difficult.

Behavioural change

The report identifies the difficulties with changing production to achieve a further decrease in emissions and goes on to look at lifestyle issues.

It highlights that one-third of all food produced, and having incurred the emissions in doing so, is wasted. A severe cut in food waste is an obvious staring point in the issue with emissions from agriculture and food.

The other point that will be controversial with farmers is the identification of ruminant livestock (cattle and sheep) as the main perpetrators in farming.

It recommends a switch to poultry and pigmeat as alternative proteins to beef and lamb, given that their emissions are estimated by the report using the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (UNFAO) data.

It shows that beef, including dairy cows, generates 46.2kg CO2e/kg of protein, lamb 35.8kg CO2e/kg of protein, pigmeat 5.8kg CO2e/kg of protein and poultry is 5.2kg CO2e/kg of protein.

The report suggests that beef and lamb per-capita consumption should be halved. Interestingly, dairy has a very low 2.8kg CO2e/kg of protein - this is because the role of the cow in dairy production is accounted for in the beef category.

There is nothing particularly new in the McKinsey report, although such is their standing globally with governments and international organisations that they are key influencers of decision-makers.

Proteins such as pigmeat and poultry are in the ascendancy anyway for commercial reasons more than emissions content in satisfying the global demand for protein.

Beef and lamb are more expensive, luxury products and increasing demand for these is from developing countries that consume more as the wealth of their citizens increases.

Nowhere demonstrated this more than China, which imported negligible quantities of beef in the first decade of this century to becoming the biggest importer in the world during the second decade.

Beef, and to a lesser extent lamb, has endured an extremely negative press for several years, yet the global demand continues to grow, even if it is static in Europe and the USA.

There is going to be a global demand for beef, so it is a case of meeting that demand in the way that does least damage to the environment.

This is achieved by targeting production to areas of the world that have tracts of marginal grassland, unsuitable for other productive agriculture and immediate access to water.

That means beef and lamb production to service global demand should be encouraged in the marginal lands of Ireland, Britain, western France, Belgium and northwestern Spain, plus areas of Scandinavia and the Netherlands.

Grassland areas with water supply in North and South America, New Zealand and some parts of Australia are also suitable.

What isn’t sensible is deep-well irrigation and import of concentrated feed into arid areas of the world to produce livestock.

Read more

Colm McCarthy: common sense needed

Environmental opportunity for NI agriculture

Fossil fuels v agriculture emissions - a skewed debate

SHARING OPTIONS