Bradley Heins is a professor at the University of Minnesota. His research interests include genetics and organic milk production and he supervises the dairy herds at the state university farm. The Irish Farmers Journal

asked Bradley some questions about dairy breeding in the US, the direction of travel and sire selection practices at the University of Minnesota. Q. Of the main breeds on US farms, how do they compare in terms of economic breeding value?

Bradley Heins is a professor at the University of Minnesota. His research interests include genetics and organic milk production and he supervises the dairy herds at the state university farm. The Irish Farmers Journal

asked Bradley some questions about dairy breeding in the US, the direction of travel and sire selection practices at the University of Minnesota.

Q. Of the main breeds on US farms, how do they compare in terms of economic breeding value?

A. All of the breeds in the US have been making genetic progress for our Lifetime Net Merit index. It is difficult to compare breeds based on economic breeding value in the USA because the Net Merits for each breed are on their own scale, and therefore difficult to compare across breeds. However, we do know that all breeds, even the minor ones, have been making genetic progress.

Q. What are the expected benefits, if any, of high genetic merit crossbreeding over and above high genetic merit within-breed selection?

A. There are many benefits to crossbreeding compared to within-breed selection. We have just completed a 10-year study of crossbreeding with bulls from two European breeds (Montbéliarde and Viking Red) compared with Holsteins in large commercial dairies in the US.

Here are some of the benefits that we found for crossbred cows versus Holsteins:

Higher daily fat plus protein during the lifetime of cows.Lower stillbirth rates.12 to 17 fewer days open.Health treatment costs were 17% to 23% lower for crossbreds compared with Holsteins.Crossbreds had on average 150 more days in the herd.Daily profit was 9% to 13% higher for crossbreds compared with Holsteins.Q. What percentage of inseminations are to genomic sires as opposed to daughter-proven sires?

A. In the US, genomic sires are about 70% of inseminations. This is the average across the industry. However, this can be very herd specific. There are some herds that continue to only use daughter-proven sires. I am supervisor of the University of Minnesota 300-cow dairy herd. I will only use daughter-proven sires, and do not use any genomic sires for our cows and heifers. We are not the only ones doing this.

Q. Why not only use genomic sires to advance the pace of selection?

A. The adoption of genomic sires may increase the pace of selection for certain traits, especially for the production traits. However, there are consequences to this increase in genomic sire usage. The biggest consequence is the rapid increase in average inbreeding in both the Holstein and Jersey breed because of the advancement of genomics. Average inbreeding of Holstein females born in the US is 8.1%. The annual increase in inbreeding is about +0.40% right now, which is alarming.

With high inbreeding levels, we see consequences of early embryotic loss, reduced fertility, increased stillbirth, reduce health of animals and lower survival.

Q. Is this why the University of Minnesota is not using genomic bulls?

A. I use proven bulls in the University herd because I believe their genetic proofs. Many times, we see young genomic bulls at the top of the index list, and the next genetic evaluation they are not there. Many of the young bulls drop significantly in genetic value from evaluation to evaluation. That does not happen as much with the proven bulls. Their genetic proofs are much more stable. Yes, proven bulls drop as well, but the drop in genetic value is not as great as the genomic bulls. Also, inbreeding is also a factor in using proven bulls in our herd. Trying to maintain low levels of inbreeding is not easy with proven bulls either, but I think I can better manage inbreeding with the proven bulls.

Inbreeding was increasing at about +0.12% per year prior to genomics. With the introduction of genomics, we have seen inbreeding levels increase much faster. They are currently increasing at +0.40% per year. I use three to five proven bulls per year for each breed that we have. That way, I do not have to worry about the drop in genetic merit that you so often see with using a lot of genomic bulls.

Our farm is about 40% purebred Holstein and 60% crossbred. The breeds we use for crossbreeding are Jersey, Normande, Viking Red, Montbéliarde, and Holstein. We use all proven bulls for the crossbred animals as well.

The Holstein genetics are the same for the purebred and the crossbred cows. For selecting bulls, I use the Net Merit index for Holstein and Jersey. I select the highest bulls from the Net Merit index for use. I also consider pedigree with those bulls to try and minimise inbreeding for the Holsteins. For the European breeds, I use the TMI (Nordic countries) for Viking Red and ISU (France) for Normande and Montbéliarde. I select the top bulls from the list that are available in the US and that are proven bulls. I also do give consideration for A2 status of milk.

In Ireland, over 75% of all dairy inseminations are to genomically selected bulls. Considering that genomics was first introduced just over 10 years ago, its widespread adoption has been remarkable. The primary reason for this is that genomically selected bulls have a higher EBI than daughter-proven bulls. So if farmers want to increase the EBI of their herd quickly, using genomic bulls will be the way to achieve that.

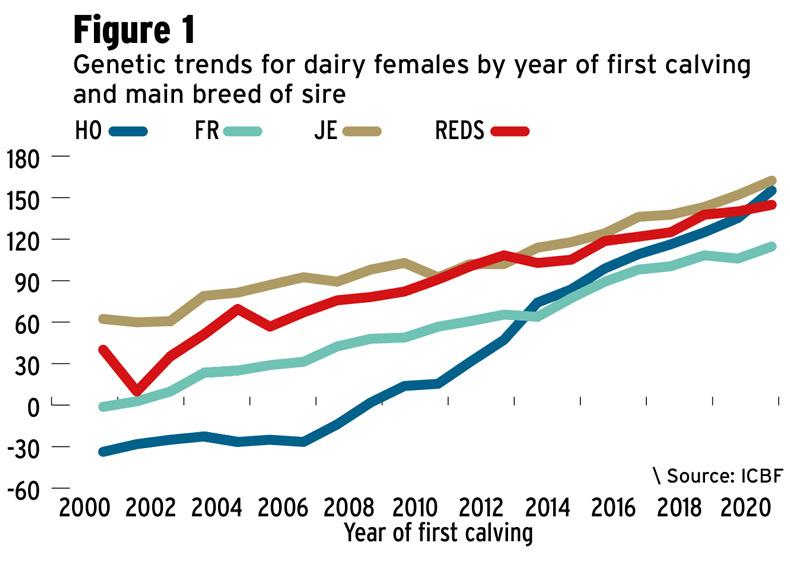

Figure 1 shows the average EBI of all first-lactation cows in the year they enter the herd for each breed.

Since 2007, the EBI of the Holstein breed has been rising at a much faster pace than the other breeds, including Friesian. Over the last 20 years, first-lactation cows with Holstein as their main breed have gone from having an EBI of -€30, meaning they are €30 per lactation less profitable than the base cow, to having an EBI of almost €160, meaning they are €160 more profitable per lactation than the base cow – a remarkable turnaround in such a short space of time.

first-calvers are now delivering an additional €252 in profit per lactation

Nationally, the EBI of first-lactation animals is increasing by almost €13 per year. According to the ICBF, this rate of genetic gain means that compared to 10 years ago, first-calvers are now delivering an additional €252 in profit per lactation. So, all other things being equal, a farmer with 100 cows should be making an extra €25,000 more per year now, compared to 10 years ago.

Issues with proof

Questions over the accuracy of genomic predictions have been asked since genomics was introduced. Some believe genomics is over-predicting genetic values. Genomically selected bulls have a blended EBI based on their parent average EBI and their genomic evaluation, the percentage of which varies between bulls depending on how much genomic data is available. As the amount of genomic data (the reference population) for animals increases, the proportion of a young bull’s EBI that is based on genomics increases also. So if a bull has multiple ancestors that have been genotyped, the proportion of genomics in that bull’s EBI will be greater than say if only the bull’s sire was genotyped.

A third dimension is added to the blend after the bull’s daughters start milking – the daughter proof. Because information on daughter fertility is slow, a bull with daughters milking will be getting his EBI from a blend of parent average, daughter proof and genomics.

Ultimately, a daughter proof is the best determinant of a bull’s performance but as we know

The Irish Farmers Journal understands a re-evaluation of the way the ICBF blends EBIs is under way. If genomics is over- or under-predicting performance, animals with a high proportion of genomics in their proof and the longer that genomic proof is used then the more inaccurate that animal’s EBI is.

Ultimately, a daughter proof is the best determinant of a bull’s performance but as we know, a daughter proof for calving interval and survival takes years to generate. Therefore, a blend of the other available information is necessary to determine predicted performance for that bull. Depending on what is agreed, if the genomic proportion of a bull’s proof is capped at a certain percentage, that could end up reducing the EBI of some of Ireland’s highest EBI bulls calves.

Over 70% of inseminations in the US are to genomic sires, but not everyone thinks genomics is good.Prof Bradley Heins only uses daugher-proven bulls at the University of Minnesota.In Ireland, 75% of all inseminations are to genomic sires.The EBI for a bull is a blend of genomics, parent average and daughter proof (if available). Read more

Dairy breeding: an international perspective

Genetic gain: is crossbreeding redundant?

SHARING OPTIONS: