Brexit returned to the news this week, but the latest round of negotiations has been overshadowed by a UK plan for domestic legislation that could overwrite parts of the Irish protocol in the withdrawal agreement. This was seen as an attempt by the UK government to bypass the obligations in the withdrawal agreement if a

deal on future trade couldn’t be reached.

With just 112 days left until the UK will no longer participate in the EU single market, trade with the UK will be on one of these three structures, all of which are more difficult to work under than the present arrangement:

1 Comprehensive agreement with UK aligned to EU

This would be the preferred outcome for Irish farmers and exporters to Britain as the UK market would remain similar to what it is at present. There would still be the administrative cost of customs documentation and health certificates but if the value of the market was preserved, these would be tolerable. It would also mean that levels of physical inspection would be minimal. However, it is virtually certain that this will not happen as the UK is determined to establish a trade policy completely independent of the EU.

This will involve the making of new trade deals and, while the US may be the most talked about partner for an early deal, it is more likely to be with Australia and New Zealand that the first deal is made. The UK government published its strategic approach for these negotiations in June and they are already under way.

2 Basic free-trade deal

This seems the best that can be realistically hoped for at this stage. It would involve the EU and UK agreeing to no tariffs and no quotas on trade between them from 1 January next year. However, that will effectively mean a return to the pre-single-market trading arrangement, with customs and health certification being inspected at the point of entry and an increased level of physical checking of product.

It does, however, leave the UK free to make its own trade deals and a deal with Australia and New Zealand is likely to be concluded early. These are the top two sheepmeat exporting countries in the world, accounting for 70% of globally traded sheepmeat between them. Australia is the third-largest exporter of beef and New Zealand the sixth largest, and if a trade deal is concluded between them and the UK, we can expect them to quickly become established in the UK market.

While Australian cattle price is strong at present, at the equivalent of €3.95/kg, it is much lower in New Zealand at around the equivalent of €3.10/kg. This would be a serious threat to Irish exports and as the UK government’s strategic approach for the negotiations highlighted, likely to cause contraction in UK agriculture as well.

3 No deal

While no future trading relationship with the UK will be as attractive as it being part of the single market, the worst outcome is if no deal is reached. In that case, the UK would apply a tariff of 12% of the product value plus £2.53/kg (€2.82/kg) on chilled boneless beef from Ireland. It may create a tariff-free or reduced-tariff quota but if it did, it would be open to all countries that export beef. On bone-in carcase beef, the UK tariff would be 12% of value plus £1.47/kg (€1.64/kg) which would have a devastating impact on Irish beef prices given the dependency of the sector on the UK market.

If there is no deal, the UK will legislate for the application of the Irish protocol in a way that is unlikely to meet with EU approval. Any enforcement procedures on an international treaty are slow and cumbersome, so trade is likely to remain frustrated for a prolonged period. Additionally, if there is no deal, the operation of trade on the island of Ireland would quickly become frustrated.

What’s in the EU’s toolbox?

If the worst case happens and there is no deal, then Irish agri-food exports to the UK will collapse. While all sectors are exposed, dairy, sheepmeat and pigmeat do have access to alternative markets.

Poultry meat is a relatively small sector but extremely exposed with over 70% of exports going to the UK in 2019.

In terms of value to Ireland, beef is the most exposed of all, with half of all exports sent to the UK. If this market wasn’t viable, the EU would have a market emergency to deal with.

The EU has created an emergency €5bn fund to compensate sectors damaged by Brexit

The EU has emergency market support measures such as paying processors to store product for a period through private storage aid. This isn’t of much benefit for beef as freezing the higher-value cuts seriously reduces their market value. The EU can also take beef off the market by purchasing it but the price would have to be around €2.00/kg before this would be triggered so it is of no practical benefit either.

The EU has created an emergency €5bn fund to compensate sectors damaged by Brexit and while details are not yet available on how this might be operated, Irish farmers have had recent experience of access to a scheme to offset the losses caused by the pandemic and we might expect that future Brexit support schemes would operate in a similar way.

Finally the EU could decide, with an oversupply of Irish product on the EU 27 market, to trigger a closure to imports. This is something the EU would be very reluctant to do, but it did put controls in place in 2017 for rice at the request of Italy and again this year to address an oversupply of steel.

If there was an abundance of Irish beef circulating in the EU 27, it would also have to reconsider implementation of the Mercosur deal which grants access for 99,000t of South American beef and there would be no headroom to negotiate further with New Zealand and Australia for additional market access for beef, whatever about other agri products.

Dependence of the island of Ireland on

the UK market

The farming and food industry on the island of Ireland is particularly dependent on Britain as its largest customer across all sectors, but particularly dependent for beef.

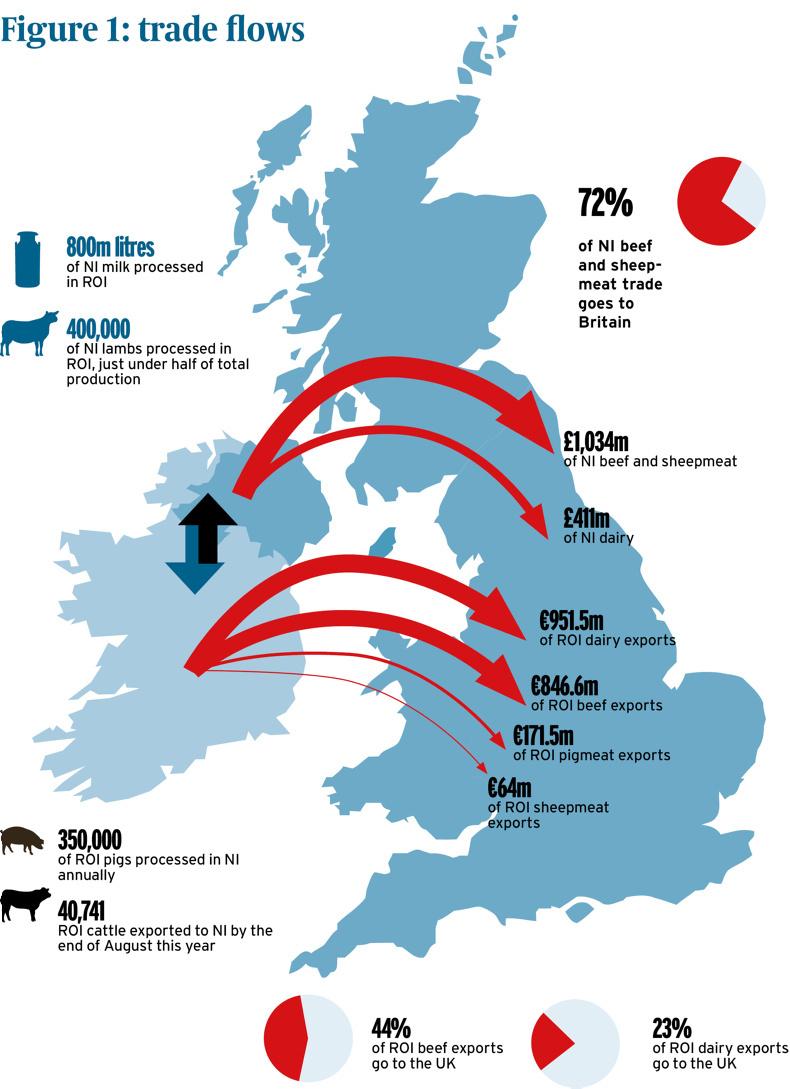

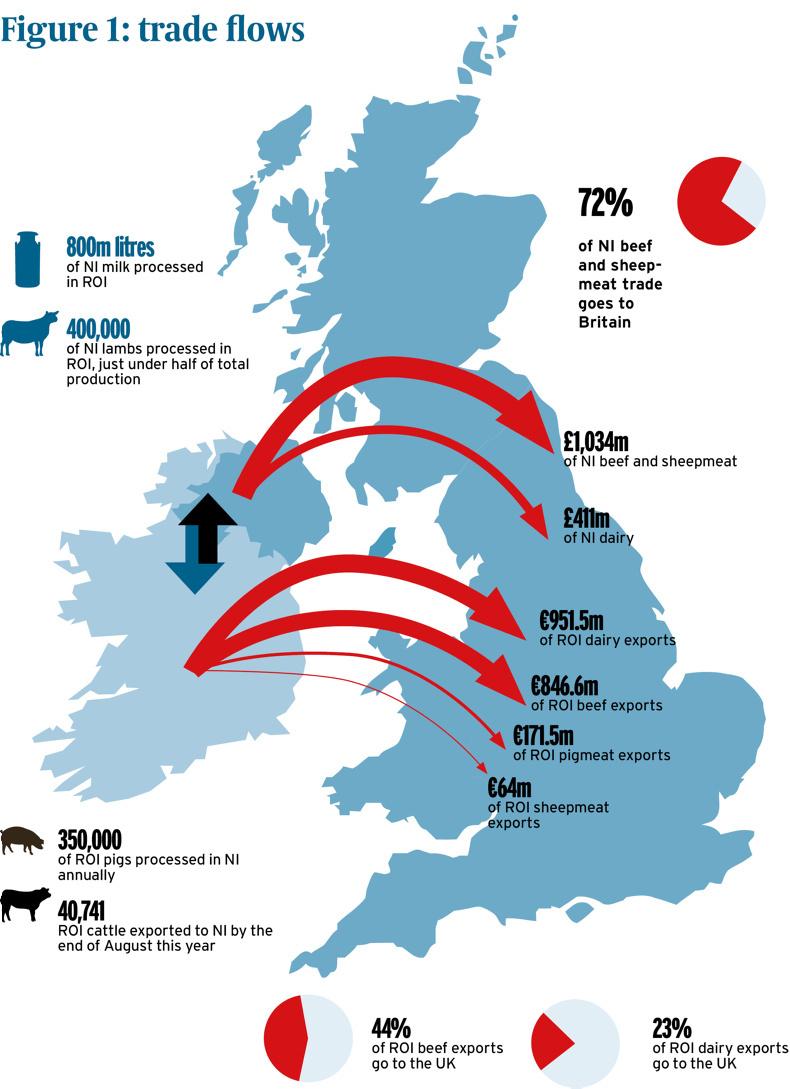

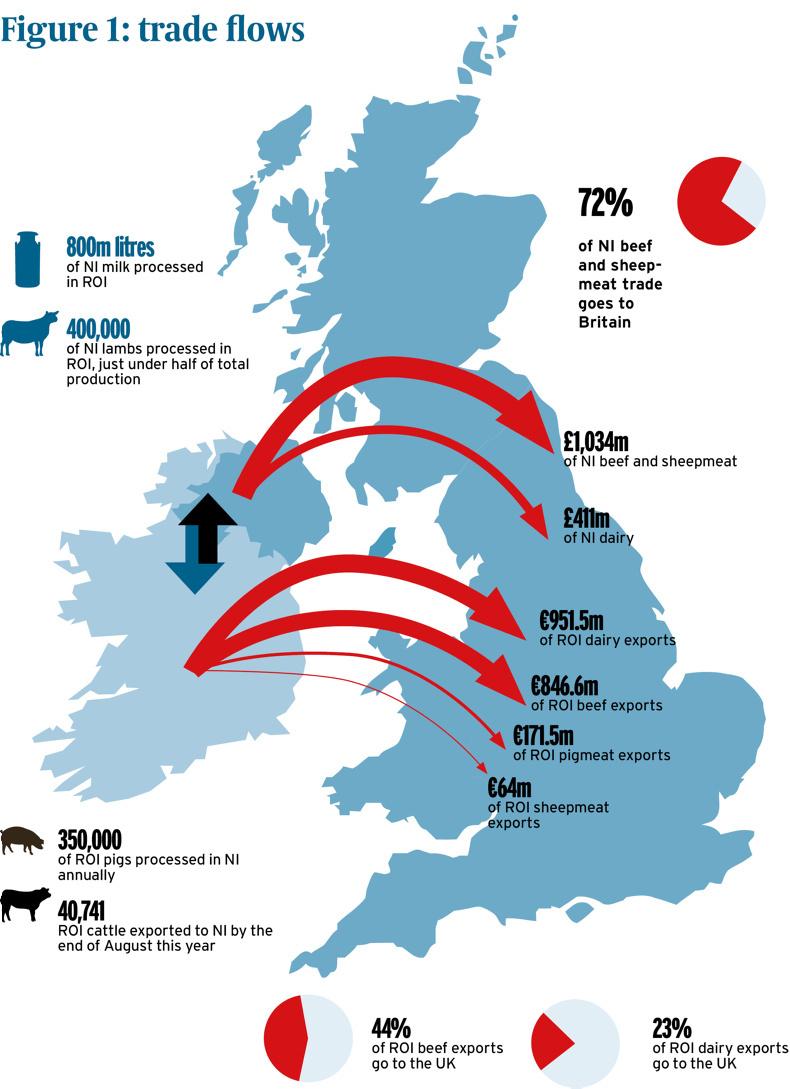

Figure 1 gives an indication of the trade flows for primary agricultural produce. Interestingly, when it comes to processed foods, the main flows are the other way from Britain to both parts of Ireland.

One of the most controversial issues in the withdrawal agreement’s Irish protocol is subjecting supermarket deliveries from distribution centres in Britain to checks and inspections for deliveries to their stores in Northern Ireland.

Cross-border trade

Trade flows both ways on the island of Ireland, with one-third of Northern Irish milk production (approximately 800m litres) processed south of the border, and it is the same for approximately 400,000 lambs, just under half of total production.

There is also a significant quantity of beef and processed milk moving from Northern Ireland to the Republic of Ireland. Over 350,000 pigs move annually from the Republic of Ireland to Northern Ireland for processing, mainly in the Karro factory in Cookstown, Co Tyrone.

Live cattle exports north have also surged this year, reaching 40,741 by the end of August, which is the equivalent of another factory.

Processed product

The UK is Ireland’s largest export market for all product categories in agri-food. Sales of Irish dairy to the UK in 2019 were €951.5m, 23% of all Irish dairy exports. Of this, €393.1m was from cheese and this is the area where Irish dairy exports are most vulnerable in Brexit.

Pigmeat sales to the UK last year were worth €171.5m from total exports of €514.6m, while sheepmeat sales to the UK were €64m in total exports that amounted to €319m.

While all these categories will be damaged by Brexit, beef is the most exposed. Exports to the UK were €846.6m in 2019 out of total exports of €1,921m, almost half. What makes beef particularly vulnerable is that there is no alternative viable market for this amount of sales, unlike dairy, pigmeat and sheepmeat, which have options in EU and wider global markets.

A significant amount of the beef deboned in Northern Ireland is from carcase beef taken into Northern Ireland from Britain, a trade that is in jeopardy unless there is a favourable deal on a future trading relationship

Northern Ireland’s beef and sheepmeat sales to Britain were £1,034m out of a total of £1,436m in 2018 or 72% of trade. A significant amount of the beef deboned in Northern Ireland is from carcase beef taken into Northern Ireland from Britain, a trade that is in jeopardy unless there is a favourable deal on a future trading relationship.

In the dairy sector, £411m from £1,143m of total sales value went to Britain from Northern Ireland.

The backstory: how Brexit came about

When the Conservative Party and the Liberal Democrats replaced the Labour government in 2010, the UK like the rest of Europe was preoccupied with recovering from the financial crash of 2008. The government pursued a policy of financial austerity and was expected to struggle in the election of 2015. The prime minister, David Cameron, in an attempt to outmanoeuvre the anti-EU UKIP party, promised a referendum on EU membership. He didn’t expect that he would secure an overall majority in the general election but when he did, the referendum was set for June 2016.

It was expected that the UK would vote by a small majority to remain in the EU but the opposite happened. David Cameron resigned immediately and was replaced by Theresa May. Her ambition was to negotiate a deal that kept the entire UK, including Northern Ireland, closely aligned with the EU. However, this wasn’t considered sufficient separation from the EU by a large number of a now seriously divided Conservative Party.

The deferral of the scheduled leaving of the EU on 29 March 2019 meant she lost the confidence of the party and was replaced by the current prime minister, Boris Johnson, who committed to deliver Brexit. He was frustrated by Parliament in the second half of 2019 but succeeded in calling a general election in December in which he secured an 80-seat majority on the almost single-issue campaign of “Getting Brexit done”. This he duly accomplished on 31 January, at which point the UK entered a transition arrangement with the EU to enable a future trade deal be negotiated. He committed that the UK would sever links with the EU customs union and single market by the end of this year irrespective of a future trading relationship being agreed.

Crunch time

The arrival of the global pandemic in February no doubt frustrated the early rounds of negotiation. These were attempted using audiovisual technology, with the chief negotiators for both sides having caught COVID-19. Face-to-face meetings resumed in July but with just over 100 days left to go, there seems little basis for a breakthrough as both sides paint a negative picture.

While prospects for a deal look bleak, this time last year a withdrawal agreement didn’t look possible yet it was secured

This week the penultimate round of discussions are taking place in London and the drama was increased by a report in the Financial Times describing how the UK was going to legislate to circumvent the Irish protocol in the withdrawal agreement in the event that a deal isn’t reached with the EU on a future trading relationship. While prospects for a deal look bleak, this time last year a withdrawal agreement didn’t look possible yet it was secured. Irish farmers and exporters will be hoping that the same happens again in the coming days or weeks.

The Irish protocol explained

The Irish/Northern Ireland (NI) protocol within the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement essentially means NI follows EU rules for goods, allowing free trade flow within Ireland, and NI companies to trade unfettered into the EU.

While the UK government has guaranteed that NI will also have unfettered access to the market in Britain, for trade in the other direction there is the potential of customs checks and tariffs.

Where a good coming into NI from Britain is deemed to be “at risk” of entering the EU, then the relevant EU tariff would have to be paid. It can be claimed back by a company if it doesn’t actually transit into the EU, but it is a messy arrangement.

Decisions around what goods are “at risk” would come down to an all-powerful UK-EU joint committee informed by a specialised committee that covers the Irish/NI protocol.

If there was a free-trade deal done between the EU and UK, this entire issue becomes minimised. But in a no-deal scenario, more controls are required at NI ports.

Comment: why this matters so much to Irish farmers

There is a temptation because of fatigue with the issue to think that Brexit doesn’t really matter as it is a UK political issue that has rumbled on for several years. The reason we haven’t felt an impact is because we won’t until after 1 January next year.

Then, depending on whether or not there is a deal, Irish farmers could be hit to the value of €1.7bn, the same amount as is received in CAP payments in the worst case scenario according to Irish Government estimates.

Many statements have been made about EU and Government solidarity with Irish farmers

The hit will be spread across all sectors but beef farmers are most exposed. Work by Andersons consulting in the UK put the administrative cost of Brexit on beef imports at between 4.5p/kg and 10p/kg depending on type of deal. In addition, huge competition is inevitable from Australia and New Zealand beef and sheepmeat for Irish exports and to a lesser extent dairy in the case of New Zealand.

Many statements have been made about EU and Government solidarity with Irish farmers. However, we are at a point where a clear course of action has to be revealed in preparing to trigger support payments if events lead to market collapse and protection of EU 27 markets. Suspending imports would be unpopular given the EU commitment to global trade, yet the exceptional circumstances would require the exceptional response of preserving an EU market for its most exposed member.

Brexit returned to the news this week, but the latest round of negotiations has been overshadowed by a UK plan for domestic legislation that could overwrite parts of the Irish protocol in the withdrawal agreement. This was seen as an attempt by the UK government to bypass the obligations in the withdrawal agreement if a

deal on future trade couldn’t be reached.

With just 112 days left until the UK will no longer participate in the EU single market, trade with the UK will be on one of these three structures, all of which are more difficult to work under than the present arrangement:

1 Comprehensive agreement with UK aligned to EU

This would be the preferred outcome for Irish farmers and exporters to Britain as the UK market would remain similar to what it is at present. There would still be the administrative cost of customs documentation and health certificates but if the value of the market was preserved, these would be tolerable. It would also mean that levels of physical inspection would be minimal. However, it is virtually certain that this will not happen as the UK is determined to establish a trade policy completely independent of the EU.

This will involve the making of new trade deals and, while the US may be the most talked about partner for an early deal, it is more likely to be with Australia and New Zealand that the first deal is made. The UK government published its strategic approach for these negotiations in June and they are already under way.

2 Basic free-trade deal

This seems the best that can be realistically hoped for at this stage. It would involve the EU and UK agreeing to no tariffs and no quotas on trade between them from 1 January next year. However, that will effectively mean a return to the pre-single-market trading arrangement, with customs and health certification being inspected at the point of entry and an increased level of physical checking of product.

It does, however, leave the UK free to make its own trade deals and a deal with Australia and New Zealand is likely to be concluded early. These are the top two sheepmeat exporting countries in the world, accounting for 70% of globally traded sheepmeat between them. Australia is the third-largest exporter of beef and New Zealand the sixth largest, and if a trade deal is concluded between them and the UK, we can expect them to quickly become established in the UK market.

While Australian cattle price is strong at present, at the equivalent of €3.95/kg, it is much lower in New Zealand at around the equivalent of €3.10/kg. This would be a serious threat to Irish exports and as the UK government’s strategic approach for the negotiations highlighted, likely to cause contraction in UK agriculture as well.

3 No deal

While no future trading relationship with the UK will be as attractive as it being part of the single market, the worst outcome is if no deal is reached. In that case, the UK would apply a tariff of 12% of the product value plus £2.53/kg (€2.82/kg) on chilled boneless beef from Ireland. It may create a tariff-free or reduced-tariff quota but if it did, it would be open to all countries that export beef. On bone-in carcase beef, the UK tariff would be 12% of value plus £1.47/kg (€1.64/kg) which would have a devastating impact on Irish beef prices given the dependency of the sector on the UK market.

If there is no deal, the UK will legislate for the application of the Irish protocol in a way that is unlikely to meet with EU approval. Any enforcement procedures on an international treaty are slow and cumbersome, so trade is likely to remain frustrated for a prolonged period. Additionally, if there is no deal, the operation of trade on the island of Ireland would quickly become frustrated.

What’s in the EU’s toolbox?

If the worst case happens and there is no deal, then Irish agri-food exports to the UK will collapse. While all sectors are exposed, dairy, sheepmeat and pigmeat do have access to alternative markets.

Poultry meat is a relatively small sector but extremely exposed with over 70% of exports going to the UK in 2019.

In terms of value to Ireland, beef is the most exposed of all, with half of all exports sent to the UK. If this market wasn’t viable, the EU would have a market emergency to deal with.

The EU has created an emergency €5bn fund to compensate sectors damaged by Brexit

The EU has emergency market support measures such as paying processors to store product for a period through private storage aid. This isn’t of much benefit for beef as freezing the higher-value cuts seriously reduces their market value. The EU can also take beef off the market by purchasing it but the price would have to be around €2.00/kg before this would be triggered so it is of no practical benefit either.

The EU has created an emergency €5bn fund to compensate sectors damaged by Brexit and while details are not yet available on how this might be operated, Irish farmers have had recent experience of access to a scheme to offset the losses caused by the pandemic and we might expect that future Brexit support schemes would operate in a similar way.

Finally the EU could decide, with an oversupply of Irish product on the EU 27 market, to trigger a closure to imports. This is something the EU would be very reluctant to do, but it did put controls in place in 2017 for rice at the request of Italy and again this year to address an oversupply of steel.

If there was an abundance of Irish beef circulating in the EU 27, it would also have to reconsider implementation of the Mercosur deal which grants access for 99,000t of South American beef and there would be no headroom to negotiate further with New Zealand and Australia for additional market access for beef, whatever about other agri products.

Dependence of the island of Ireland on

the UK market

The farming and food industry on the island of Ireland is particularly dependent on Britain as its largest customer across all sectors, but particularly dependent for beef.

Figure 1 gives an indication of the trade flows for primary agricultural produce. Interestingly, when it comes to processed foods, the main flows are the other way from Britain to both parts of Ireland.

One of the most controversial issues in the withdrawal agreement’s Irish protocol is subjecting supermarket deliveries from distribution centres in Britain to checks and inspections for deliveries to their stores in Northern Ireland.

Cross-border trade

Trade flows both ways on the island of Ireland, with one-third of Northern Irish milk production (approximately 800m litres) processed south of the border, and it is the same for approximately 400,000 lambs, just under half of total production.

There is also a significant quantity of beef and processed milk moving from Northern Ireland to the Republic of Ireland. Over 350,000 pigs move annually from the Republic of Ireland to Northern Ireland for processing, mainly in the Karro factory in Cookstown, Co Tyrone.

Live cattle exports north have also surged this year, reaching 40,741 by the end of August, which is the equivalent of another factory.

Processed product

The UK is Ireland’s largest export market for all product categories in agri-food. Sales of Irish dairy to the UK in 2019 were €951.5m, 23% of all Irish dairy exports. Of this, €393.1m was from cheese and this is the area where Irish dairy exports are most vulnerable in Brexit.

Pigmeat sales to the UK last year were worth €171.5m from total exports of €514.6m, while sheepmeat sales to the UK were €64m in total exports that amounted to €319m.

While all these categories will be damaged by Brexit, beef is the most exposed. Exports to the UK were €846.6m in 2019 out of total exports of €1,921m, almost half. What makes beef particularly vulnerable is that there is no alternative viable market for this amount of sales, unlike dairy, pigmeat and sheepmeat, which have options in EU and wider global markets.

A significant amount of the beef deboned in Northern Ireland is from carcase beef taken into Northern Ireland from Britain, a trade that is in jeopardy unless there is a favourable deal on a future trading relationship

Northern Ireland’s beef and sheepmeat sales to Britain were £1,034m out of a total of £1,436m in 2018 or 72% of trade. A significant amount of the beef deboned in Northern Ireland is from carcase beef taken into Northern Ireland from Britain, a trade that is in jeopardy unless there is a favourable deal on a future trading relationship.

In the dairy sector, £411m from £1,143m of total sales value went to Britain from Northern Ireland.

The backstory: how Brexit came about

When the Conservative Party and the Liberal Democrats replaced the Labour government in 2010, the UK like the rest of Europe was preoccupied with recovering from the financial crash of 2008. The government pursued a policy of financial austerity and was expected to struggle in the election of 2015. The prime minister, David Cameron, in an attempt to outmanoeuvre the anti-EU UKIP party, promised a referendum on EU membership. He didn’t expect that he would secure an overall majority in the general election but when he did, the referendum was set for June 2016.

It was expected that the UK would vote by a small majority to remain in the EU but the opposite happened. David Cameron resigned immediately and was replaced by Theresa May. Her ambition was to negotiate a deal that kept the entire UK, including Northern Ireland, closely aligned with the EU. However, this wasn’t considered sufficient separation from the EU by a large number of a now seriously divided Conservative Party.

The deferral of the scheduled leaving of the EU on 29 March 2019 meant she lost the confidence of the party and was replaced by the current prime minister, Boris Johnson, who committed to deliver Brexit. He was frustrated by Parliament in the second half of 2019 but succeeded in calling a general election in December in which he secured an 80-seat majority on the almost single-issue campaign of “Getting Brexit done”. This he duly accomplished on 31 January, at which point the UK entered a transition arrangement with the EU to enable a future trade deal be negotiated. He committed that the UK would sever links with the EU customs union and single market by the end of this year irrespective of a future trading relationship being agreed.

Crunch time

The arrival of the global pandemic in February no doubt frustrated the early rounds of negotiation. These were attempted using audiovisual technology, with the chief negotiators for both sides having caught COVID-19. Face-to-face meetings resumed in July but with just over 100 days left to go, there seems little basis for a breakthrough as both sides paint a negative picture.

While prospects for a deal look bleak, this time last year a withdrawal agreement didn’t look possible yet it was secured

This week the penultimate round of discussions are taking place in London and the drama was increased by a report in the Financial Times describing how the UK was going to legislate to circumvent the Irish protocol in the withdrawal agreement in the event that a deal isn’t reached with the EU on a future trading relationship. While prospects for a deal look bleak, this time last year a withdrawal agreement didn’t look possible yet it was secured. Irish farmers and exporters will be hoping that the same happens again in the coming days or weeks.

The Irish protocol explained

The Irish/Northern Ireland (NI) protocol within the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement essentially means NI follows EU rules for goods, allowing free trade flow within Ireland, and NI companies to trade unfettered into the EU.

While the UK government has guaranteed that NI will also have unfettered access to the market in Britain, for trade in the other direction there is the potential of customs checks and tariffs.

Where a good coming into NI from Britain is deemed to be “at risk” of entering the EU, then the relevant EU tariff would have to be paid. It can be claimed back by a company if it doesn’t actually transit into the EU, but it is a messy arrangement.

Decisions around what goods are “at risk” would come down to an all-powerful UK-EU joint committee informed by a specialised committee that covers the Irish/NI protocol.

If there was a free-trade deal done between the EU and UK, this entire issue becomes minimised. But in a no-deal scenario, more controls are required at NI ports.

Comment: why this matters so much to Irish farmers

There is a temptation because of fatigue with the issue to think that Brexit doesn’t really matter as it is a UK political issue that has rumbled on for several years. The reason we haven’t felt an impact is because we won’t until after 1 January next year.

Then, depending on whether or not there is a deal, Irish farmers could be hit to the value of €1.7bn, the same amount as is received in CAP payments in the worst case scenario according to Irish Government estimates.

Many statements have been made about EU and Government solidarity with Irish farmers

The hit will be spread across all sectors but beef farmers are most exposed. Work by Andersons consulting in the UK put the administrative cost of Brexit on beef imports at between 4.5p/kg and 10p/kg depending on type of deal. In addition, huge competition is inevitable from Australia and New Zealand beef and sheepmeat for Irish exports and to a lesser extent dairy in the case of New Zealand.

Many statements have been made about EU and Government solidarity with Irish farmers. However, we are at a point where a clear course of action has to be revealed in preparing to trigger support payments if events lead to market collapse and protection of EU 27 markets. Suspending imports would be unpopular given the EU commitment to global trade, yet the exceptional circumstances would require the exceptional response of preserving an EU market for its most exposed member.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: