It’s something of an anomaly that the phrase ‘the new normal’ has pervaded our everyday speech, given that it seems that nothing stays the same for long enough to actually become an accepted custom.

For four months or so, we had no GAA at all; then, when things resumed at the end of July, there was a limit of 200 people, including players, management and officials. That didn’t last too long before games had to go behind closed doors in the Republic, even if the wily few were able to evade security measures; and September brought a relaxation of measures as 200 patrons were once again permitted at club games.

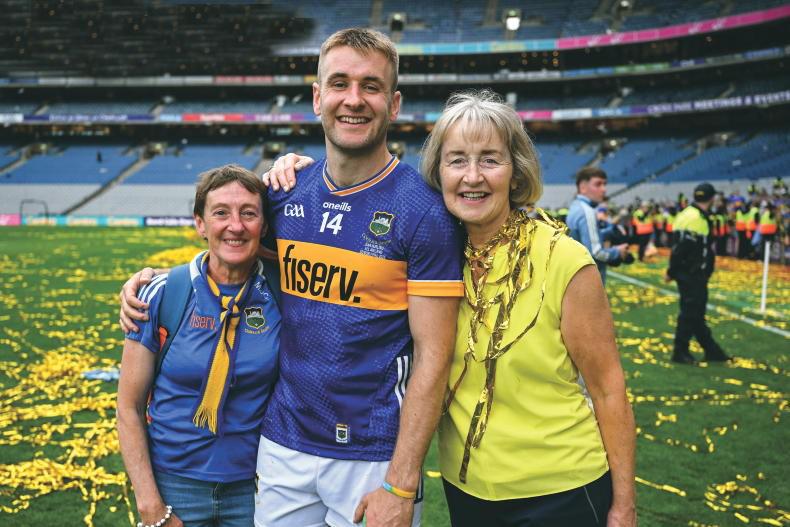

With such a compacted club season, there was only a two-month period at most between county championship opening games and finals and it is the latter, and the subsequent over-exuberant celebrations, which informed the GAA’s decision on Monday to issue a suspension of club activity at all levels across the island of Ireland.

Given the push by the National Public Health Emergency Team (NPHET) for the implementation of Level 5 in terms of COVID-19 planning, the taking of some action by the GAA wouldn’t have been a huge surprise but a blanket ban on games shocked many – especially as the Government ultimately only went as far as Level 3 restrictions, which allows for ‘elite-level sport’ (club and county games in GAA terms) to be played, albeit behind closed doors.

Celebration concern

Even so, it looks as if the GAA won’t reverse the original decision and outstanding county finals will have to be fitted in around the inter-county season, if and when that gets under way. While Blackrock, who ended an 18-year wait for a Cork hurling title, took much of the negative attention on Monday in the wake of celebrations where social-distancing was at a minimum, GAA top brass had been left concerned with a number of such examples that hadn’t been as widely reported.

Even if Level 3 is only in place for a short period, it will be a while yet before full houses at games are experienced again in any sport. Recently, speaking to an Oireachtas committee, IRFU chief executive Philip Browne laid out the stark scenario that would result from a long spell without paying spectators – to the extent that rugby’s very future would be under threat.

Finances

“Pre-COVID-19, our financial situation was looking quite positive,” he said.

“Now, we are facing an unprecedented cashflow crisis, as we try to work towards the objectives of protecting our national men’s, women’s and provincial teams, ensuring that we preserve the amateur club game and support the jobs of our 500 employees to the extent that we can.

“The current projected position to the end of June 2021, showing a negative cash swing of almost €40m from a cash surplus of some €28m in June 2020, to borrowings of just over €10m, backed by union assets, is very serious and is being kept under constant review.

“If these projections were to materialise, the very existence of professional rugby on the island would be under significant threat in 2021. Our audited financial statements for the period to July 31, 2020 will show an actual record financial loss of more than €35m.

“Back in January 2020, we were forecasting for a planned deficit of €3.5m. Until we can admit spectators in meaningful numbers into our stadia, and return to some level approaching self-sustainability, the whole rugby infrastructure built over the last 150 years is under threat.”

Breaking the ‘chain’

While the GAA’s model differs in that it doesn’t have to pay the salaries of professional players in the same way rugby does, the empty stadiums present a similar challenge in terms of financing the organisation but there is also a social cost.

This was outlined by John Considine, an All-Ireland hurling winner with Cork in 1990 and an economics lecturer in UCC, in a recent Irish Times piece.

He made the point that there is a ‘chain’ in that most adults who attend games do so because they were brought as children and the cycle is ever-repeating. However, if people get used to consuming games on their televisions or devices, that pattern can become frayed.

“If this persists, yes, there’ll be a bounce-back in terms of: ‘Isn’t it great to get back to see a championship game live?’ but how widespread and sustained will it be?” he asked.

“You could get it but there is that danger that you lose even just 15 percent, who decided they have other things to do. My worry is that this will stick in a small but significant cohort.

“I don’t know the answer because there is no data on which to base an opinion – it’s never happened before – or even a strong feeling but it’s a danger and a worry for the GAA that a number of people will decide: ‘That doesn’t suit me’, and sit down and watch a game streamed or broadcast instead.”

Ultimately, nobody knows what’s going to happen or when we’ll have the “old normal” back. For now, all we can hope is that public behaviour can help to improve the situation.

Heneghan’s high

hopes for Connacht

In terms of Irish sport, it was unfortunate in the extreme that this year of all years should be the one affected by a global pandemic, given the effort that had been put into the 20x20 campaign.

A disrupted calendar hopefully won’t prove terminal in hampering the aims of various women’s sports and sporting organisations and, in any case, there have still been notable successes.

Rugby referee Joy Neville made history as she was appointed as the first female television match official for two of the Autumn Nations Cup games scheduled for November, Wales v Georgia and Scotland v Fiji, but the Limerick native also found time to hail another Irish woman breaking a barrier in rugby.

Ann Heneghan of Partry in Co Mayo is the new president of Connacht Rugby, the first woman to hold such a role at provincial level and Neville spoke for all of us when she tweeted: “Massive congratulations. Unbelievable achievement. The first of many no doubt #cantseecantbe.”

Heneghan, the owner of a law firm, was a key activist in the creation of the Connacht Rugby Supporters’ Club in 2003, when the team’s very existence was in danger.

She hopes that she can pave a way for others to follow.

“There’s no reason why a woman couldn’t have done it before now, though I’d hate to think it’s happened now just for the sake of positive discrimination,” she said.

“I’m happy to know that I’ve put in the years and earned my stripes, if you like. From a personal point of view, I’d love to see more women getting involved, not just in Connacht but throughout the four provinces.

“There was always going to be somebody who was the first to do it and maybe it will encourage more women to stick in there, hang in there in what they do and see how far they can get. I think it brings a good balance if you’ve got women in roles in what would traditionally have been a male-dominated sport, not so much anymore but certainly when I would have got involved initially, I would have been in that type of scenario.”

It’s something of an anomaly that the phrase ‘the new normal’ has pervaded our everyday speech, given that it seems that nothing stays the same for long enough to actually become an accepted custom.

For four months or so, we had no GAA at all; then, when things resumed at the end of July, there was a limit of 200 people, including players, management and officials. That didn’t last too long before games had to go behind closed doors in the Republic, even if the wily few were able to evade security measures; and September brought a relaxation of measures as 200 patrons were once again permitted at club games.

With such a compacted club season, there was only a two-month period at most between county championship opening games and finals and it is the latter, and the subsequent over-exuberant celebrations, which informed the GAA’s decision on Monday to issue a suspension of club activity at all levels across the island of Ireland.

Given the push by the National Public Health Emergency Team (NPHET) for the implementation of Level 5 in terms of COVID-19 planning, the taking of some action by the GAA wouldn’t have been a huge surprise but a blanket ban on games shocked many – especially as the Government ultimately only went as far as Level 3 restrictions, which allows for ‘elite-level sport’ (club and county games in GAA terms) to be played, albeit behind closed doors.

Celebration concern

Even so, it looks as if the GAA won’t reverse the original decision and outstanding county finals will have to be fitted in around the inter-county season, if and when that gets under way. While Blackrock, who ended an 18-year wait for a Cork hurling title, took much of the negative attention on Monday in the wake of celebrations where social-distancing was at a minimum, GAA top brass had been left concerned with a number of such examples that hadn’t been as widely reported.

Even if Level 3 is only in place for a short period, it will be a while yet before full houses at games are experienced again in any sport. Recently, speaking to an Oireachtas committee, IRFU chief executive Philip Browne laid out the stark scenario that would result from a long spell without paying spectators – to the extent that rugby’s very future would be under threat.

Finances

“Pre-COVID-19, our financial situation was looking quite positive,” he said.

“Now, we are facing an unprecedented cashflow crisis, as we try to work towards the objectives of protecting our national men’s, women’s and provincial teams, ensuring that we preserve the amateur club game and support the jobs of our 500 employees to the extent that we can.

“The current projected position to the end of June 2021, showing a negative cash swing of almost €40m from a cash surplus of some €28m in June 2020, to borrowings of just over €10m, backed by union assets, is very serious and is being kept under constant review.

“If these projections were to materialise, the very existence of professional rugby on the island would be under significant threat in 2021. Our audited financial statements for the period to July 31, 2020 will show an actual record financial loss of more than €35m.

“Back in January 2020, we were forecasting for a planned deficit of €3.5m. Until we can admit spectators in meaningful numbers into our stadia, and return to some level approaching self-sustainability, the whole rugby infrastructure built over the last 150 years is under threat.”

Breaking the ‘chain’

While the GAA’s model differs in that it doesn’t have to pay the salaries of professional players in the same way rugby does, the empty stadiums present a similar challenge in terms of financing the organisation but there is also a social cost.

This was outlined by John Considine, an All-Ireland hurling winner with Cork in 1990 and an economics lecturer in UCC, in a recent Irish Times piece.

He made the point that there is a ‘chain’ in that most adults who attend games do so because they were brought as children and the cycle is ever-repeating. However, if people get used to consuming games on their televisions or devices, that pattern can become frayed.

“If this persists, yes, there’ll be a bounce-back in terms of: ‘Isn’t it great to get back to see a championship game live?’ but how widespread and sustained will it be?” he asked.

“You could get it but there is that danger that you lose even just 15 percent, who decided they have other things to do. My worry is that this will stick in a small but significant cohort.

“I don’t know the answer because there is no data on which to base an opinion – it’s never happened before – or even a strong feeling but it’s a danger and a worry for the GAA that a number of people will decide: ‘That doesn’t suit me’, and sit down and watch a game streamed or broadcast instead.”

Ultimately, nobody knows what’s going to happen or when we’ll have the “old normal” back. For now, all we can hope is that public behaviour can help to improve the situation.

Heneghan’s high

hopes for Connacht

In terms of Irish sport, it was unfortunate in the extreme that this year of all years should be the one affected by a global pandemic, given the effort that had been put into the 20x20 campaign.

A disrupted calendar hopefully won’t prove terminal in hampering the aims of various women’s sports and sporting organisations and, in any case, there have still been notable successes.

Rugby referee Joy Neville made history as she was appointed as the first female television match official for two of the Autumn Nations Cup games scheduled for November, Wales v Georgia and Scotland v Fiji, but the Limerick native also found time to hail another Irish woman breaking a barrier in rugby.

Ann Heneghan of Partry in Co Mayo is the new president of Connacht Rugby, the first woman to hold such a role at provincial level and Neville spoke for all of us when she tweeted: “Massive congratulations. Unbelievable achievement. The first of many no doubt #cantseecantbe.”

Heneghan, the owner of a law firm, was a key activist in the creation of the Connacht Rugby Supporters’ Club in 2003, when the team’s very existence was in danger.

She hopes that she can pave a way for others to follow.

“There’s no reason why a woman couldn’t have done it before now, though I’d hate to think it’s happened now just for the sake of positive discrimination,” she said.

“I’m happy to know that I’ve put in the years and earned my stripes, if you like. From a personal point of view, I’d love to see more women getting involved, not just in Connacht but throughout the four provinces.

“There was always going to be somebody who was the first to do it and maybe it will encourage more women to stick in there, hang in there in what they do and see how far they can get. I think it brings a good balance if you’ve got women in roles in what would traditionally have been a male-dominated sport, not so much anymore but certainly when I would have got involved initially, I would have been in that type of scenario.”

SHARING OPTIONS