Food security has been driving the development of modern civilisation since the beginning of time – to be reminded of this, I need only look at the ring fort in our back field. I often wonder what it must have been like for its residents all those millennia ago. They were protecting themselves from potential attacks, sure, but equally, the ring provided food security. The space within could hold livestock. The surrounding trees provided food. The design of a ring fort, back then, made sense in ways other than the most obvious.

In her books Hungry City (2008) and Sitopia (2020), British author, lecturer and architect Carolyn Steel examines how food has shaped society and how it can guide us in the future. In a more recent article (June, 2020), she maintains that – historically speaking – societies which did not “value food” did not tend to survive for long.

“Valuing food is all about understanding how to balance the two essential sets of relationships in our lives: those between us and our fellow humans, and those between us and nature,” she writes. “The fact that food is what binds us most powerfully to both is what gives it its unrivalled importance and transformative potential.”

Her words remind me of permaculture: a design philosophy which can be applied to agriculture, urban and community development, and a way, for some, to achieve their own form of food sovereignty.

Permaculture adheres to three broad ethical elements: Earth care (environment), people care (community) and fair share (yield). It was founded in Australia and, in many ways, mirrors Indigenous (or aboriginal) approaches to land management.

In Ireland, permaculture is practised both in rural and urban areas – it works in any sized space. You will often see permaculture running in parallel with a small business, like a restaurant or an eco-tourism site.

The Gourmet Offensive, Galway

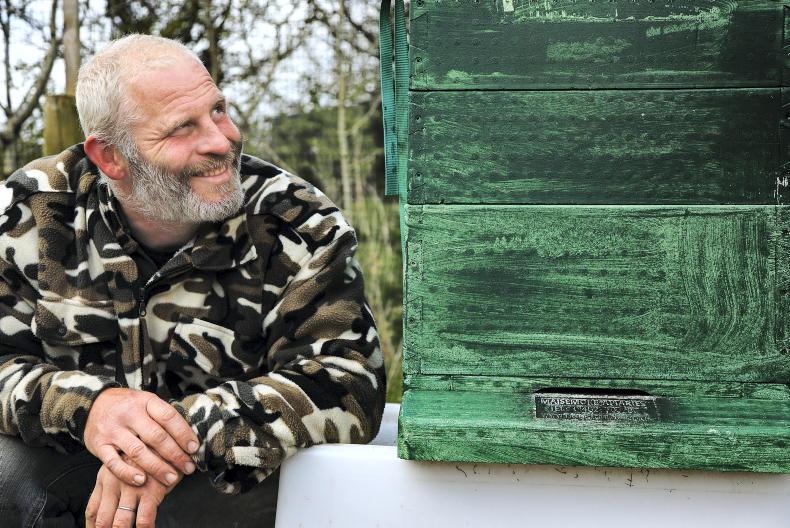

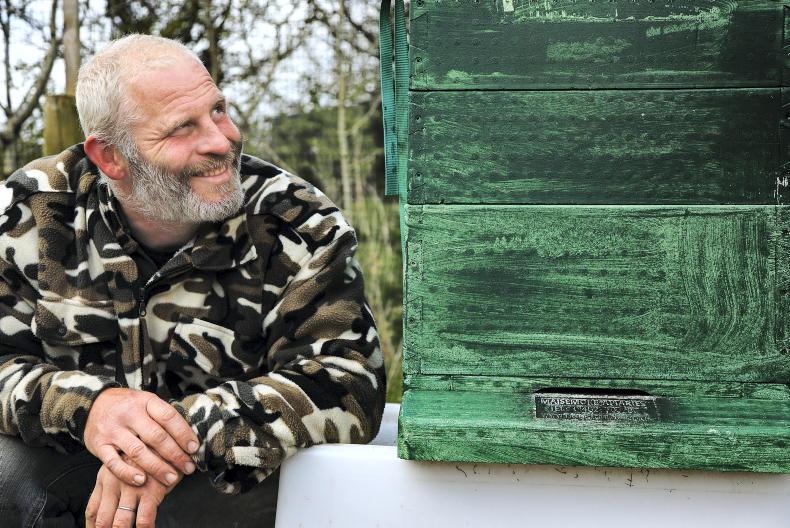

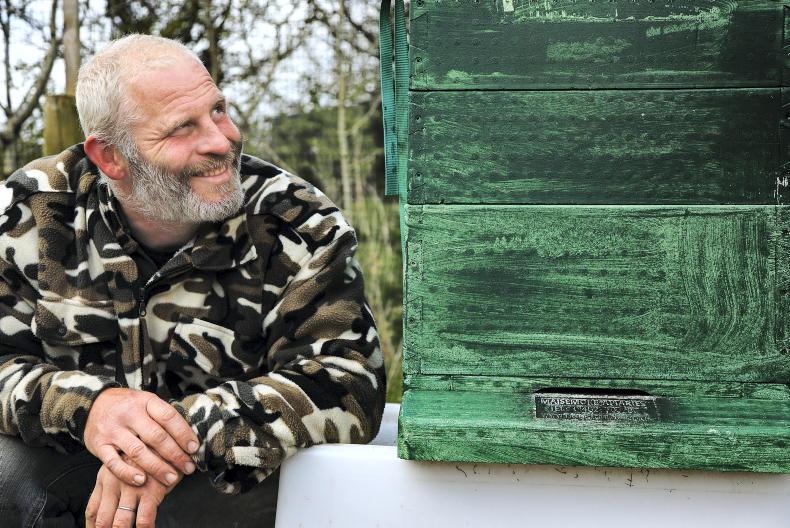

Floris Wagemakers moved to Galway from The Netherlands in 1999. \ Claire Nash

“I think permaculture is an individual choice,” Floris Wagemakers says. “During the first recession [in 2008], my food business grew really fast and I was still quite young. Mistakes were made; I started struggling with the way the world works and I felt powerless, in a way. What permaculture did for me was, it made me feel empowered.”

Floris owns The Gourmet Offensive restaurant in Galway and specialises in making falafel. \ Claire Nash

Floris, who is originally from the Netherlands, came to Galway in 1999. He grew up in an agricultural area and his parents grew food and kept chickens in their small backyard.

Perhaps this is part of the reason why permaculture makes such sense to him, since it can be practised in small areas (he originally started growing vegetables in eight raised beds in a market garden).

Floris's urban approach to permaculture means he uses as much of his own food for his restaurant and sends the waste back to the farm. \ Claire Nash

From market to field

“I started [selling falafel] at the Galway market in 2005 and that became very popular,” he says.

“I then expanded into festivals and catering. When the recession hit, I scaled down to just the market stall and leased some land outside of Tuam. Before I did that, I did a permaculture design course in Cork and had been growing food in the market garden.

“For six years, I applied as much as I knew and also started keeping some livestock. We were growing so much food, I thought, ‘This is the time to open a restaurant’ – and that’s what I did in 2015.

“I underestimated the amount of work that would go into [The Gourmet Offensive], though,” he continues.

The Gourmet Offensive in Galway. \ Claire Nash

“Within the first year, I had to give up the land (because of lack of time and finances). The initial idea was to service the restaurant with that piece of land, but what actually happened was I made so many contacts with other farmers and growers; we started working with four farms; all within a 20km radius, and they supply us with all of our vegetables.”

Urban reality

Floris says moving back to the city after spending time in the country was a difficult adjustment, but like anything with permaculture, you simply observe your environment and find the best way to enhance the natural surroundings.

“It’s a change in mindset,” he says. “You look at your space and see what you can achieve in it. I have a tiny front garden and it’s planted absolutely everywhere. In an urban setting, community involvement is probably the most important aspect of permaculture. For example, some of the farmers I work with are young and have not established routes to market yet, so we’ll be setting up a pop-up farm shop this summer to test the waters. They’ll be selling vegetables and plants in the heart of the city. Whatever is not sold will be used in the restaurant.”

In terms of financial viability, Floris says his business model was never set up to be massively profitable. However, he does believe that if you can supply as much of your own food as possible, you can offset common restaurant costs.

“Sure, there is a philosophy behind what I do, but I have a family, as well, and I have to make enough money to live,” he explains.

Floris Wagemakers practises permaculture in Co Galway. \ Claire Nash

“If I were buying my vegetables from a larger supplier I’d be spending around €60,000 per year. If you can grow all that yourself, you won’t make the money the first or second year, but eventually you’re saving a lot of money. Not including labour, of course, but on a two-acre market garden, with hand machinery, you can produce a lot of food.”

An Irish falafel

As he specialises in making falafel (a Middle Eastern dish usually made with spiced chickpeas), one of Floris’s goals is to find an Irish farmer to supply him with broad beans. This would enable him to stop importing chickpeas for his falafel, which is the main ingredient he still has to bring in from outside Galway.

“We go through around a tonne [of chickpeas] a year,” he says. “I have been looking for Irish-grown broad beans and while Irish farmers sometimes feed them to cows, they can also make a great falafel. If I could get broad beans and Irish-grown parsley, I would have a 100% Irish falafel – which would be amazing. Broad beans fix nitrogen into the soil, as well, so it would be a win-win situation.”

Thomas and Claire O’Connor

Manna Organic Farm and Store, Tralee

Thomas and Claire O'Connor, with Ciara their dog, on their farm. \ Valerie O'Sullivan

In 2007, Thomas and Claire O’Connor were publicans with no experience in farming or running a small food business. However, they were drawn to the concept of permaculture and organic farming. They wanted to eat more locally produced organic foods and they wanted greater access to these types of foods. They assumed they weren’t the only ones, so they sold their pub, created Manna Organic Farm and Store and never looked back.

On their 25ac mixed farm, they produce organic vegetables, salads, meat, wheatgrass and eggs. The farm includes four acres of permaculture forest, comprised of native fruit trees and shrubs. The farm also includes 13ac of native woodland. They sell their product directly in the shop, from which they also sell produce from other local organic farmers, as well as organic product from around Ireland and, when necessary, imports from other countries.

No-fly zone

“Our mantra is ‘Kerry first’,” explains Claire. “Then Ireland, then and – only then – we import. People want things like peppers and courgettes all year round, and that season is very short in Ireland, so we import those, for example. We have a no-fly policy, so everything imported is shipped. The furthest would be our bananas, ginger and turmeric, which come from the Dominican Republic and Peru.”

Thomas says their goal was to be more self-sustaining, to be able to provide food for the local community and to benefit their overall environment. That is part of what attracted them to permaculture.

“Ten to 15% of what we sell in the shop comes from the farm – the shop is our main income, but the farm is growing,” he says. “We get busier each year, but it took a long time to get to a break-even point on the farm. It was originally a sheep farm with rye grass. We took the three main fields, added 13ac of woodland and then we have our manna field which is four acres, with six different sections in rotation.

Food forest

“Our permaculture section is four acres with fruit trees in a mixed system,” he continues. “It was an open field, but we took that four acres and divided it into seven sections with hedgerows. The trees are part of the environment. We wanted to grow food and have access to good food. We knew if we created a healthy, diverse environment, whatever we grew would be good. We started saving our own seeds [a few years ago] and we do more of that each year.”

By saving seeds, growing their own food and creating a healthy, biodiverse environment, Thomas feels he and Claire are creating their own form of food security.

Permaculture principles

“The first principle of permaculture is observe and interact; see what nature looks like before you act,” he says. “Capture the energy of your farm, obtain a yield – always ensure you make a living.

Thomas says this type of farming is hard work and it takes years for pay off, but it's a great way of life. \ Valerie O'Sullivan

“It’s more of a broad guideline of how to approach your environment. It applies well to agriculture. Permaculture looks at what your inputs are, and what you’re growing and exporting off your farm. Everything we grow on the farm ends up in the shop, then the waste from the shop comes back into the farm.”

COVID-19 and Brexit

Claire says food security has become even more important in the past year, with the COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit taking place at the same time.

“We’re at this since 2007,” she says. “We thought we were busy then, but the demand [for organic product] has increased year on year and the business has grown every year. This past year it has just been out the ballpark. The week the words COVID hit the TV; the growth was instantaneous.

Some of the vegetables Thomas grows for Manna Organic Store in Tralee. \ Valerie O'Sullivan

“We had to adjust to meet demand, I took on new staff, I have someone just to manage the stock room now,” she continues.

“It wasn’t as much the pandemic as Brexit – I realised there would be continuity problems, so I rented more space and put in a Brexit stockroom, which has been such a relief. We occasionally run out of some things, but I’m keeping about six weeks of stock at a time.”

Demand for organic

Claire says their work on the farm and in the shop is rewarding, but it’s hard work to grow food.

“When we started out, we were told, ‘If you don’t have 200ac, you can’t make a living’. That’s not the case anywhere else in the world, so why would it be an issue here? You only need half an acre and onwards to be growing vegetables in Ireland.

“Our business is financially sustainable, but it wouldn’t be if we were only selling food from Ireland,” she says.

Thomas and Claire transformed the farm, which was originally for sheep, into a mixed organic farm with native Irish woodland and a permaculture food forest. \ Valerie O'Sullivan

“The demand for organic food has increased we’ve noticed a lot of new customers this past year, with average spend gone up among our customers.”

Aside from the three ethics of permaculture, there are also 12 design principles to incorporate into your space. These principles are specifically vague so you can adapt them to your particular environment:

1 Observe and interact (look at your land and consider what changes need to be made before you act – maybe your land is ideal for fruit trees, or maybe it’s boggy and would work with rewetting).

2 Catch and store energy (develop systems to collect resources at peak abundance for use in times of need – Floris says one of the farmers he works with captures excess heat from their glass houses, for example).

3 Whatever you do, always obtain a yield. If your endeavour isn’t self-sustaining, it isn’t worthwhile.

4 Apply self-regulation and accept feedback from others within the permaculture community (this will help ensure your system functions to the best of its abilities).

5 Use renewable resources; reduce consumption and dependence on non-renewable resources.

6 Produce no waste.

7 Design from patterns (observe patterns in nature or society and use them – what naturally grows well on your land, and where? Use that information to plan new areas for growing food).

8 Integrate rather than segregate (let nature take over – chickens will naturally want to go into the forest; things will naturally go to seed if unharvested).

9 Use small and slow solutions (don’t use synthetic chemicals on your land).

10 Use and value diversity.

11 Use edges; value the marginal (borders are where the most interesting events take place).

12 Creatively use and respond to change (for example, use the waste from your farm in compost).

If you want to learn more about permaculture, there are design courses throughout the country. Simply search for a permaculture design course to find one near you or visit permaculture.ie.

Food security has been driving the development of modern civilisation since the beginning of time – to be reminded of this, I need only look at the ring fort in our back field. I often wonder what it must have been like for its residents all those millennia ago. They were protecting themselves from potential attacks, sure, but equally, the ring provided food security. The space within could hold livestock. The surrounding trees provided food. The design of a ring fort, back then, made sense in ways other than the most obvious.

In her books Hungry City (2008) and Sitopia (2020), British author, lecturer and architect Carolyn Steel examines how food has shaped society and how it can guide us in the future. In a more recent article (June, 2020), she maintains that – historically speaking – societies which did not “value food” did not tend to survive for long.

“Valuing food is all about understanding how to balance the two essential sets of relationships in our lives: those between us and our fellow humans, and those between us and nature,” she writes. “The fact that food is what binds us most powerfully to both is what gives it its unrivalled importance and transformative potential.”

Her words remind me of permaculture: a design philosophy which can be applied to agriculture, urban and community development, and a way, for some, to achieve their own form of food sovereignty.

Permaculture adheres to three broad ethical elements: Earth care (environment), people care (community) and fair share (yield). It was founded in Australia and, in many ways, mirrors Indigenous (or aboriginal) approaches to land management.

In Ireland, permaculture is practised both in rural and urban areas – it works in any sized space. You will often see permaculture running in parallel with a small business, like a restaurant or an eco-tourism site.

The Gourmet Offensive, Galway

Floris Wagemakers moved to Galway from The Netherlands in 1999. \ Claire Nash

“I think permaculture is an individual choice,” Floris Wagemakers says. “During the first recession [in 2008], my food business grew really fast and I was still quite young. Mistakes were made; I started struggling with the way the world works and I felt powerless, in a way. What permaculture did for me was, it made me feel empowered.”

Floris owns The Gourmet Offensive restaurant in Galway and specialises in making falafel. \ Claire Nash

Floris, who is originally from the Netherlands, came to Galway in 1999. He grew up in an agricultural area and his parents grew food and kept chickens in their small backyard.

Perhaps this is part of the reason why permaculture makes such sense to him, since it can be practised in small areas (he originally started growing vegetables in eight raised beds in a market garden).

Floris's urban approach to permaculture means he uses as much of his own food for his restaurant and sends the waste back to the farm. \ Claire Nash

From market to field

“I started [selling falafel] at the Galway market in 2005 and that became very popular,” he says.

“I then expanded into festivals and catering. When the recession hit, I scaled down to just the market stall and leased some land outside of Tuam. Before I did that, I did a permaculture design course in Cork and had been growing food in the market garden.

“For six years, I applied as much as I knew and also started keeping some livestock. We were growing so much food, I thought, ‘This is the time to open a restaurant’ – and that’s what I did in 2015.

“I underestimated the amount of work that would go into [The Gourmet Offensive], though,” he continues.

The Gourmet Offensive in Galway. \ Claire Nash

“Within the first year, I had to give up the land (because of lack of time and finances). The initial idea was to service the restaurant with that piece of land, but what actually happened was I made so many contacts with other farmers and growers; we started working with four farms; all within a 20km radius, and they supply us with all of our vegetables.”

Urban reality

Floris says moving back to the city after spending time in the country was a difficult adjustment, but like anything with permaculture, you simply observe your environment and find the best way to enhance the natural surroundings.

“It’s a change in mindset,” he says. “You look at your space and see what you can achieve in it. I have a tiny front garden and it’s planted absolutely everywhere. In an urban setting, community involvement is probably the most important aspect of permaculture. For example, some of the farmers I work with are young and have not established routes to market yet, so we’ll be setting up a pop-up farm shop this summer to test the waters. They’ll be selling vegetables and plants in the heart of the city. Whatever is not sold will be used in the restaurant.”

In terms of financial viability, Floris says his business model was never set up to be massively profitable. However, he does believe that if you can supply as much of your own food as possible, you can offset common restaurant costs.

“Sure, there is a philosophy behind what I do, but I have a family, as well, and I have to make enough money to live,” he explains.

Floris Wagemakers practises permaculture in Co Galway. \ Claire Nash

“If I were buying my vegetables from a larger supplier I’d be spending around €60,000 per year. If you can grow all that yourself, you won’t make the money the first or second year, but eventually you’re saving a lot of money. Not including labour, of course, but on a two-acre market garden, with hand machinery, you can produce a lot of food.”

An Irish falafel

As he specialises in making falafel (a Middle Eastern dish usually made with spiced chickpeas), one of Floris’s goals is to find an Irish farmer to supply him with broad beans. This would enable him to stop importing chickpeas for his falafel, which is the main ingredient he still has to bring in from outside Galway.

“We go through around a tonne [of chickpeas] a year,” he says. “I have been looking for Irish-grown broad beans and while Irish farmers sometimes feed them to cows, they can also make a great falafel. If I could get broad beans and Irish-grown parsley, I would have a 100% Irish falafel – which would be amazing. Broad beans fix nitrogen into the soil, as well, so it would be a win-win situation.”

Thomas and Claire O’Connor

Manna Organic Farm and Store, Tralee

Thomas and Claire O'Connor, with Ciara their dog, on their farm. \ Valerie O'Sullivan

In 2007, Thomas and Claire O’Connor were publicans with no experience in farming or running a small food business. However, they were drawn to the concept of permaculture and organic farming. They wanted to eat more locally produced organic foods and they wanted greater access to these types of foods. They assumed they weren’t the only ones, so they sold their pub, created Manna Organic Farm and Store and never looked back.

On their 25ac mixed farm, they produce organic vegetables, salads, meat, wheatgrass and eggs. The farm includes four acres of permaculture forest, comprised of native fruit trees and shrubs. The farm also includes 13ac of native woodland. They sell their product directly in the shop, from which they also sell produce from other local organic farmers, as well as organic product from around Ireland and, when necessary, imports from other countries.

No-fly zone

“Our mantra is ‘Kerry first’,” explains Claire. “Then Ireland, then and – only then – we import. People want things like peppers and courgettes all year round, and that season is very short in Ireland, so we import those, for example. We have a no-fly policy, so everything imported is shipped. The furthest would be our bananas, ginger and turmeric, which come from the Dominican Republic and Peru.”

Thomas says their goal was to be more self-sustaining, to be able to provide food for the local community and to benefit their overall environment. That is part of what attracted them to permaculture.

“Ten to 15% of what we sell in the shop comes from the farm – the shop is our main income, but the farm is growing,” he says. “We get busier each year, but it took a long time to get to a break-even point on the farm. It was originally a sheep farm with rye grass. We took the three main fields, added 13ac of woodland and then we have our manna field which is four acres, with six different sections in rotation.

Food forest

“Our permaculture section is four acres with fruit trees in a mixed system,” he continues. “It was an open field, but we took that four acres and divided it into seven sections with hedgerows. The trees are part of the environment. We wanted to grow food and have access to good food. We knew if we created a healthy, diverse environment, whatever we grew would be good. We started saving our own seeds [a few years ago] and we do more of that each year.”

By saving seeds, growing their own food and creating a healthy, biodiverse environment, Thomas feels he and Claire are creating their own form of food security.

Permaculture principles

“The first principle of permaculture is observe and interact; see what nature looks like before you act,” he says. “Capture the energy of your farm, obtain a yield – always ensure you make a living.

Thomas says this type of farming is hard work and it takes years for pay off, but it's a great way of life. \ Valerie O'Sullivan

“It’s more of a broad guideline of how to approach your environment. It applies well to agriculture. Permaculture looks at what your inputs are, and what you’re growing and exporting off your farm. Everything we grow on the farm ends up in the shop, then the waste from the shop comes back into the farm.”

COVID-19 and Brexit

Claire says food security has become even more important in the past year, with the COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit taking place at the same time.

“We’re at this since 2007,” she says. “We thought we were busy then, but the demand [for organic product] has increased year on year and the business has grown every year. This past year it has just been out the ballpark. The week the words COVID hit the TV; the growth was instantaneous.

Some of the vegetables Thomas grows for Manna Organic Store in Tralee. \ Valerie O'Sullivan

“We had to adjust to meet demand, I took on new staff, I have someone just to manage the stock room now,” she continues.

“It wasn’t as much the pandemic as Brexit – I realised there would be continuity problems, so I rented more space and put in a Brexit stockroom, which has been such a relief. We occasionally run out of some things, but I’m keeping about six weeks of stock at a time.”

Demand for organic

Claire says their work on the farm and in the shop is rewarding, but it’s hard work to grow food.

“When we started out, we were told, ‘If you don’t have 200ac, you can’t make a living’. That’s not the case anywhere else in the world, so why would it be an issue here? You only need half an acre and onwards to be growing vegetables in Ireland.

“Our business is financially sustainable, but it wouldn’t be if we were only selling food from Ireland,” she says.

Thomas and Claire transformed the farm, which was originally for sheep, into a mixed organic farm with native Irish woodland and a permaculture food forest. \ Valerie O'Sullivan

“The demand for organic food has increased we’ve noticed a lot of new customers this past year, with average spend gone up among our customers.”

Aside from the three ethics of permaculture, there are also 12 design principles to incorporate into your space. These principles are specifically vague so you can adapt them to your particular environment:

1 Observe and interact (look at your land and consider what changes need to be made before you act – maybe your land is ideal for fruit trees, or maybe it’s boggy and would work with rewetting).

2 Catch and store energy (develop systems to collect resources at peak abundance for use in times of need – Floris says one of the farmers he works with captures excess heat from their glass houses, for example).

3 Whatever you do, always obtain a yield. If your endeavour isn’t self-sustaining, it isn’t worthwhile.

4 Apply self-regulation and accept feedback from others within the permaculture community (this will help ensure your system functions to the best of its abilities).

5 Use renewable resources; reduce consumption and dependence on non-renewable resources.

6 Produce no waste.

7 Design from patterns (observe patterns in nature or society and use them – what naturally grows well on your land, and where? Use that information to plan new areas for growing food).

8 Integrate rather than segregate (let nature take over – chickens will naturally want to go into the forest; things will naturally go to seed if unharvested).

9 Use small and slow solutions (don’t use synthetic chemicals on your land).

10 Use and value diversity.

11 Use edges; value the marginal (borders are where the most interesting events take place).

12 Creatively use and respond to change (for example, use the waste from your farm in compost).

If you want to learn more about permaculture, there are design courses throughout the country. Simply search for a permaculture design course to find one near you or visit permaculture.ie.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: