If you get bitten by a snake in Ireland and dial emergency services, you will be put through to the National Poisons Information Service in Beaumont Hospital.

They, in turn, will immediately call a man in Kilkenny. Why? Because James Hennessey’s reptile zoo is the only place in Ireland that will have the anti-venom to save your life.

James is from Callan – a town not known for its abseiling or fixed-wing aircraft enthusiasts – so after school, following a family tradition, he joined the military, coming out as an adventure sports instructor. It was at this point he started leading expeditions into the tropics – from Belize to central South America, from Asia to Africa.

Although even when he was very young James had snakes and lizards, it was through scientific research that he was afforded the opportunity to see “some of the bigger and the weirder stuff in the wild”.

“I got an option to do it in the military and then because I had qualifications like mountain leader, climbing instructor and various map reading skills, I was able to take teams of people into the forest.”

With this set of skills he was able to get to places others couldn’t get to, he explains.

“So let’s say you wanted to survey down along the side of a cliff in a rainforest, you have to know ropes, have climbing abilities, you have to be able to navigate your way into it. So your usual scientists who comes out of college with a degree don’t tend to have that skillset.”

However, he admits, there was no steady income in the adventure sports side of things or travelling, so just before the boom, James got into construction, building up a small business. He made some money but unlike his contemporaries, he didn’t buy a second house, he opened a zoo.

Gauging interest

Even when working in construction, James’s interest in reptiles or research didn’t wane. His personal reptile collection was getting bigger and he constantly had people knocking on his door to see them. He knew that the interest in the animals was there and that was an opportunity for education.

He laughs telling me of the local suspicions.

“This was in Callan and I had these insulated units outside, glowing red lights and it had people thinking I was growing things I shouldn’t have been growing.”

An upcycled carbon free zoo

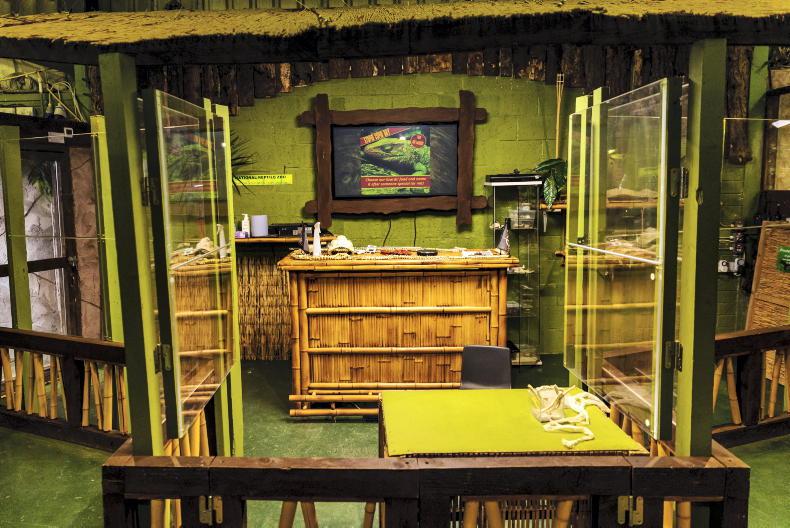

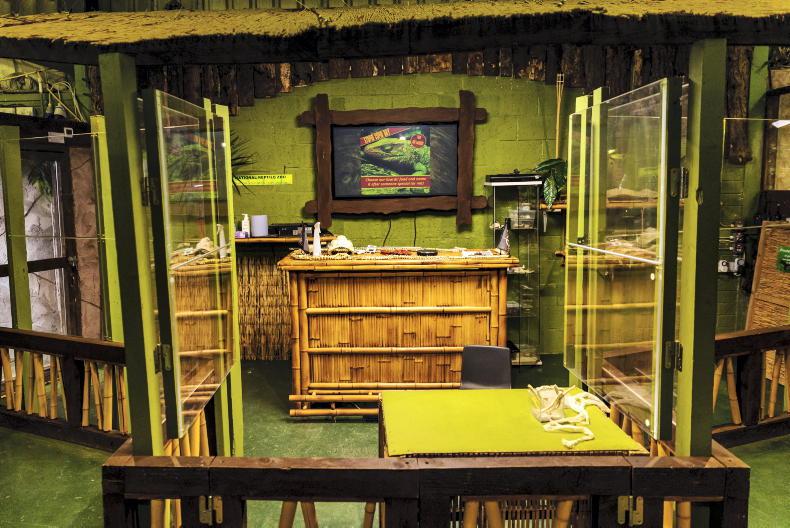

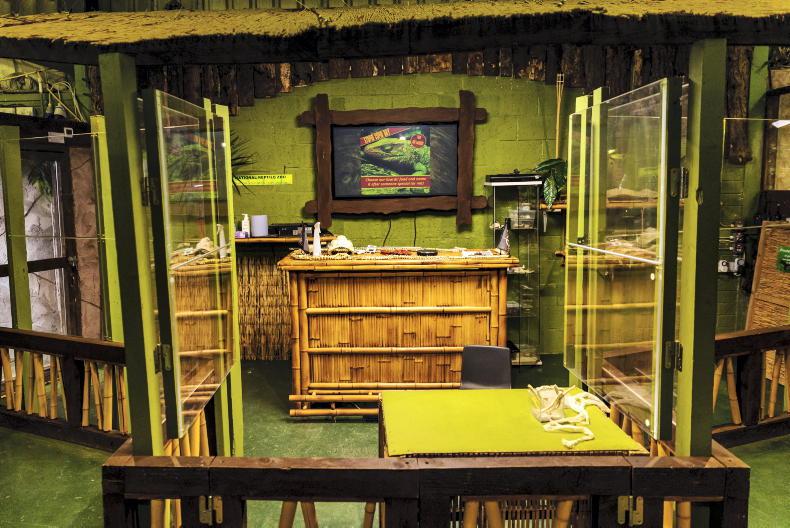

The zoo recently moved from a smaller premises in Gowran to Kilkenny city and James admits that he had learned a lot by the time he built the second one. Everything in the new zoo, within reason, is upcycled.

“We [James and his brother] got the clay blocks in Wexford so they have a zero carbon footprint, the windows I got from shopping centres that closed down or were miss measured, we got the timbers from a garden centre in Cork that closed down and the Perspex is from old bus shelters. We upcycled half the building in that everything within the building, bar electrics, has come from somewhere else.”

Research and conservation

To have a zoo licence you must operate under the European zoo directive and for that your operation must be involved in conservation, research and education.

To James, “they are not just animals in boxes for entertainment, it is quite the opposite – they all serve a purpose. They are either educating people about their plight in the wild or we’re gathering data from them or we are keeping them as a genetic backup for species should they disappear. So we don’t just pick any animal, we pick them because we can use them for education or because they are endangered.”

To explain how the research programme works, James shows us his venomous Gila monsters from New Mexico. Each lizard has its own individual tags and QR code and when we descend on the sealed venomous rooms, the lizards are being weighed.

“We’ve got digital files on each of these guys. So anytime we do anything with them, weigh them, check humidity, temperature or the ultraviolet readings off their lamps, we’re taking readings and studying what they do. It’s noted down on their digital file,” James describes.

You can tell that conservation is his passion.

“We are kind of like an ark for species in the wild so as they disappear we’ve got ones that are kept as the ones in the wild would be and they are acclimatised to go back into the wild if need be,” he says.

“If there is a decline in the wild, we can look at how they thrive in captivity, what they like and what they don’t like. Then we can look at the situation in the wild and if something’s not matching up, we’ve got this massive database that goes back years.”

The venom from the Gila monsters is chewed in, he tells us, as he holds her across his arm. They have a venom gland on their lower jaw so when handling them, the keeper wears venom defender gloves. All the keepers are trained in handling venomous snakes and reptiles and the crocodiles. This means that if they are needed to work in the field, they have people who are used to working with the specific animal.

Why, I cautiously ask, would the keepers need to work “in the field” in safe venom-free little old Ireland?

Size really doesn’t matter

The reason is in a small glass box. Nestled inside is a 50cm semi-cute brown snake that was found in Offaly in a pallet of slate tiles that came over from India. She looks at us curiously, posing for her photograph – but looks can be deceiving and James tells us that this little creature is a saw-scaled viper, the snake “responsible for probably the most deaths across the world.”

James Hennessey pictured with a boa constrictor. \ Philip Doyle

“They’re common, they will sit under rocks and will bite when someone picks up building materials or is walking in bare feet and they step on the snake,” says James.

The Reptile Zoo gets a lot of calls like that call from Offaly and, in most cases, the snake is harmless like a corn snake. The problem, he warns, is that corn snakes looks a lot like our deadly friend in the glass box.

Human animal conflict

In terms of conservation, James says that “you’ve got to work a bit harder with the scaly stuff”.

“If you tell somebody that a tiger cub is endangered, they look cute and people buy in. Whereas trying to tell people a crocodile that’s killing people or a deadly snake is an important species and we should keep it is much harder.

“The animals have a niche habitat and position in the environment. And they are an important part of it – especially the big apex predators, the big venomous snakes, crocodiles, alligators – as they tend to be responsible for maintaining the ecosystem.”

The zoo funds a number of in-situ projects in Uganda, Guatemala, India and Sri Lanka. James’s specialist area is human-animal conflict, which means that, for example, in Sri Lanka he trains the wildlife department and the vet department on capture and ethical relocation of crocodiles.

“The Sri Lankans don’t kill the crocs. So if somebody gets eaten by a crocodile, they want to move it but the problem is they know how to catch them but they don’t know how to transport them. Also they release them into the wrong place and it causes a problem for other animals in that area. So we’re there to advise them, assess the situation and assist them.”

However, in Uganda, where there are a huge number of people getting eaten by crocodiles in the village James is working with, the attitude is different, he tells us.

“We are trying to develop ways that people can coexist with the crocs but their argument is the same. Why can’t we just kill all these crocs? This is on the massive Lake Edward near Lake Victoria. They want to kill all the crocs but the crocs are keeping the fish populations healthy. Our job is to explain that if you take out all the crocs, the fish population will get out of control with more predators than prey species, which will impact the human food supply.”

Snakes in Ireland?

Ireland is actually one of only a small number of countries, others being New Zealand, Iceland, Greenland, and Antarctica that there are no snakes, but this has nothing to do with St Patrick. No, the allegorical snakes banished by our patron saint were the pagans.

James says that given the timeframe for St Patrick – the fifth century, which in the grand scheme is not that long ago – if there were snakes, “we would definitely have them in the fossil record”. It was a mixture of the last Ice Age keeping Ireland too cold and then by the time it ended, the land bridges by which snakes could have slithered onto the island had been cut off as the continents and countries separated.

So there it is: “Fake Snake News” in the fifth century.

The experience

With education, the reptile zoo has been going out to schools for many years, but during COVID-19, the tours went digital and global. The most recent was a school in Hawaii, teaching the kids about invasive species.

Digital is fine James says, but with the conservation, nothing beats the feeling of a reptile in your hands.

The zoo is self-guided but there is an encounter area where visitors can get closer to the animals.

For more details on the zoo tours, education and conservation programmes, visit www.nationalreptilezoo.ie

Read more

Minding the flock with rural chaplain Kenny Hanna

Living Life: Paudie Maher on his hurling career

If you get bitten by a snake in Ireland and dial emergency services, you will be put through to the National Poisons Information Service in Beaumont Hospital.

They, in turn, will immediately call a man in Kilkenny. Why? Because James Hennessey’s reptile zoo is the only place in Ireland that will have the anti-venom to save your life.

James is from Callan – a town not known for its abseiling or fixed-wing aircraft enthusiasts – so after school, following a family tradition, he joined the military, coming out as an adventure sports instructor. It was at this point he started leading expeditions into the tropics – from Belize to central South America, from Asia to Africa.

Although even when he was very young James had snakes and lizards, it was through scientific research that he was afforded the opportunity to see “some of the bigger and the weirder stuff in the wild”.

“I got an option to do it in the military and then because I had qualifications like mountain leader, climbing instructor and various map reading skills, I was able to take teams of people into the forest.”

With this set of skills he was able to get to places others couldn’t get to, he explains.

“So let’s say you wanted to survey down along the side of a cliff in a rainforest, you have to know ropes, have climbing abilities, you have to be able to navigate your way into it. So your usual scientists who comes out of college with a degree don’t tend to have that skillset.”

However, he admits, there was no steady income in the adventure sports side of things or travelling, so just before the boom, James got into construction, building up a small business. He made some money but unlike his contemporaries, he didn’t buy a second house, he opened a zoo.

Gauging interest

Even when working in construction, James’s interest in reptiles or research didn’t wane. His personal reptile collection was getting bigger and he constantly had people knocking on his door to see them. He knew that the interest in the animals was there and that was an opportunity for education.

He laughs telling me of the local suspicions.

“This was in Callan and I had these insulated units outside, glowing red lights and it had people thinking I was growing things I shouldn’t have been growing.”

An upcycled carbon free zoo

The zoo recently moved from a smaller premises in Gowran to Kilkenny city and James admits that he had learned a lot by the time he built the second one. Everything in the new zoo, within reason, is upcycled.

“We [James and his brother] got the clay blocks in Wexford so they have a zero carbon footprint, the windows I got from shopping centres that closed down or were miss measured, we got the timbers from a garden centre in Cork that closed down and the Perspex is from old bus shelters. We upcycled half the building in that everything within the building, bar electrics, has come from somewhere else.”

Research and conservation

To have a zoo licence you must operate under the European zoo directive and for that your operation must be involved in conservation, research and education.

To James, “they are not just animals in boxes for entertainment, it is quite the opposite – they all serve a purpose. They are either educating people about their plight in the wild or we’re gathering data from them or we are keeping them as a genetic backup for species should they disappear. So we don’t just pick any animal, we pick them because we can use them for education or because they are endangered.”

To explain how the research programme works, James shows us his venomous Gila monsters from New Mexico. Each lizard has its own individual tags and QR code and when we descend on the sealed venomous rooms, the lizards are being weighed.

“We’ve got digital files on each of these guys. So anytime we do anything with them, weigh them, check humidity, temperature or the ultraviolet readings off their lamps, we’re taking readings and studying what they do. It’s noted down on their digital file,” James describes.

You can tell that conservation is his passion.

“We are kind of like an ark for species in the wild so as they disappear we’ve got ones that are kept as the ones in the wild would be and they are acclimatised to go back into the wild if need be,” he says.

“If there is a decline in the wild, we can look at how they thrive in captivity, what they like and what they don’t like. Then we can look at the situation in the wild and if something’s not matching up, we’ve got this massive database that goes back years.”

The venom from the Gila monsters is chewed in, he tells us, as he holds her across his arm. They have a venom gland on their lower jaw so when handling them, the keeper wears venom defender gloves. All the keepers are trained in handling venomous snakes and reptiles and the crocodiles. This means that if they are needed to work in the field, they have people who are used to working with the specific animal.

Why, I cautiously ask, would the keepers need to work “in the field” in safe venom-free little old Ireland?

Size really doesn’t matter

The reason is in a small glass box. Nestled inside is a 50cm semi-cute brown snake that was found in Offaly in a pallet of slate tiles that came over from India. She looks at us curiously, posing for her photograph – but looks can be deceiving and James tells us that this little creature is a saw-scaled viper, the snake “responsible for probably the most deaths across the world.”

James Hennessey pictured with a boa constrictor. \ Philip Doyle

“They’re common, they will sit under rocks and will bite when someone picks up building materials or is walking in bare feet and they step on the snake,” says James.

The Reptile Zoo gets a lot of calls like that call from Offaly and, in most cases, the snake is harmless like a corn snake. The problem, he warns, is that corn snakes looks a lot like our deadly friend in the glass box.

Human animal conflict

In terms of conservation, James says that “you’ve got to work a bit harder with the scaly stuff”.

“If you tell somebody that a tiger cub is endangered, they look cute and people buy in. Whereas trying to tell people a crocodile that’s killing people or a deadly snake is an important species and we should keep it is much harder.

“The animals have a niche habitat and position in the environment. And they are an important part of it – especially the big apex predators, the big venomous snakes, crocodiles, alligators – as they tend to be responsible for maintaining the ecosystem.”

The zoo funds a number of in-situ projects in Uganda, Guatemala, India and Sri Lanka. James’s specialist area is human-animal conflict, which means that, for example, in Sri Lanka he trains the wildlife department and the vet department on capture and ethical relocation of crocodiles.

“The Sri Lankans don’t kill the crocs. So if somebody gets eaten by a crocodile, they want to move it but the problem is they know how to catch them but they don’t know how to transport them. Also they release them into the wrong place and it causes a problem for other animals in that area. So we’re there to advise them, assess the situation and assist them.”

However, in Uganda, where there are a huge number of people getting eaten by crocodiles in the village James is working with, the attitude is different, he tells us.

“We are trying to develop ways that people can coexist with the crocs but their argument is the same. Why can’t we just kill all these crocs? This is on the massive Lake Edward near Lake Victoria. They want to kill all the crocs but the crocs are keeping the fish populations healthy. Our job is to explain that if you take out all the crocs, the fish population will get out of control with more predators than prey species, which will impact the human food supply.”

Snakes in Ireland?

Ireland is actually one of only a small number of countries, others being New Zealand, Iceland, Greenland, and Antarctica that there are no snakes, but this has nothing to do with St Patrick. No, the allegorical snakes banished by our patron saint were the pagans.

James says that given the timeframe for St Patrick – the fifth century, which in the grand scheme is not that long ago – if there were snakes, “we would definitely have them in the fossil record”. It was a mixture of the last Ice Age keeping Ireland too cold and then by the time it ended, the land bridges by which snakes could have slithered onto the island had been cut off as the continents and countries separated.

So there it is: “Fake Snake News” in the fifth century.

The experience

With education, the reptile zoo has been going out to schools for many years, but during COVID-19, the tours went digital and global. The most recent was a school in Hawaii, teaching the kids about invasive species.

Digital is fine James says, but with the conservation, nothing beats the feeling of a reptile in your hands.

The zoo is self-guided but there is an encounter area where visitors can get closer to the animals.

For more details on the zoo tours, education and conservation programmes, visit www.nationalreptilezoo.ie

Read more

Minding the flock with rural chaplain Kenny Hanna

Living Life: Paudie Maher on his hurling career

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: