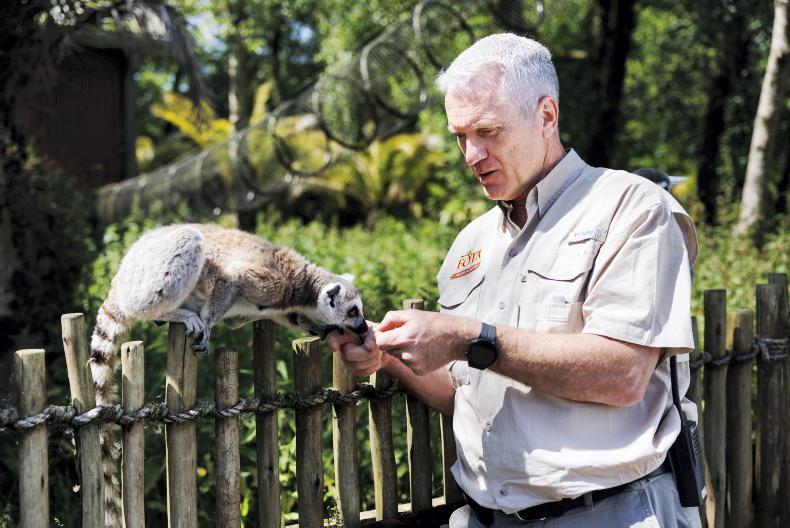

As animal care manager at Fota Wildlife Park, Declan O’Donovan is responsible for the 108 exotic species at the 100-acre park collection.

Yet, his love of nature did not start on the Serengeti or in the rainforest - it started on dairy farms.

Hailing from Bishopstown, Co Cork, Declan was exposed to the world of animal care from an early age as his father, Sean O’Donovan was a dairy science lecturer and farm manager for University College Cork (UCC).

“As I was growing up around the farm, I always had that special sort of attraction and affinity to animals,” he explains.

After the purchase of Fota Estate by UCC in 1976, Declan witnessed first-hand the transformation of Fota Estate over the years. In fact, he even remembers his father sitting at the kitchen table and drawing up plans for some of the houses for the initial animals coming in during the establishment of Fota Wildlife Park, in 1983.

Paving a pathway

When Declan finished school in the early 1980s, employment was scarce.

“When I left school, I was like many kids, all I wanted to do was leave. I had no desire to go to university,” he says.

As the wildlife park was setting up, however, they were looking for staff. Declan ended up working for Fota as an animal keeper in the early days, until 1988,when he left to go to university in the UK.

“I did a behavioural ecology degree. And from there I travelled around a little bit, I spent a year in Australia, where I worked in Perth Zoo as one of their keepers,” he explains.

After another stint in Ireland, Declan went to the Middle East, where he stayed for 23 years. During that time, he established a successful cheetah breeding programme at the Wadi Al Safa Wildlife Centre in Dubai.

In the last 20 years, amongst other notable achievements, this centre has bred over 90 critically endangered northern cheetahs, many of which have been sent to Europe to establish a core breeding population for the European Association Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA).

“[They] set up studbooks so that they ensure the correct animals go and breed with the correct animals so you maintain the genetic diversity of the population,” explains Declan.

“We were also involved with one of the bigger breeding facilities for cheetahs. We supplied a number of animals to breeding programmes here in Europe. Here in Fota, we still have two of those animals, which we sent over.”

Animal care manager

Due to a number of factors with family members getting older and his children going to university in Europe, Declan and his wife decided to return to Ireland.

Another major attraction to coming home for Declan was being offered the opportunity to be involved with native Irish wildlife conservation in Fota Wildlife Park as their animal care manager. This involves working with rangers and making sure that the welfare of animals is looked after.

“There were no issues beforehand, but we’re just putting some policies and procedures into place so that it can all be documented. And we can go back and we can see what works, or what doesn’t work,” he explains.

Speaking about the most rewarding part of his job, Declan tells Irish Country Living that he loves to see the passion that some of the younger rangers have for the animals they care for, while he also enjoys breeding particular species that he knows will go towards future release.

“Even if we’re just a reserve for animals that are needed later on, we’re happy to do that because we know that somebody needs to keep them and make sure they are safe and protected,” he explains.

Money from a conservation budget also contributes to different projects that Fota are involved in. This is part of their responsibilities in EAZA.

“We also support PhD students and undergraduate students in some of the research work that they do both here in the wildlife park, in UCC and at other universities,” he says.

For Declan, research is very valuable and he supports and encourages anybody in it as he believes that “it’s the only way we learn.”

Indeed, Declan himself conducted one of the earliest animal welfare research projects, which focused on the impact of visitors on the behaviour of captive cheetahs and their cubs.

He also holds a master’s degree in conservation biology, where he researched the physiological and morphometric features of the Arabian oryx. He is currently awaiting the defence of his PhD at UCC, which examined the use of translocation of a threatened, large terrestrial reptile species in the Emirate of Dubai.

Native species

The importance of Ireland’s native species, however, cannot be overlooked, as Declan emphasises.

“In a lot of cases, people mentioned the rainforest declining at certain rates and things, but you don’t have to go outside of Ireland to see the damage to very sensitive areas,” he says.

“Unless we start looking at trying to help and support what we have here in Ireland, then I think it’s a little bit hypocritical to a certain extent.”

Fota Wildlife Park is taking a leadership role in the conservation of native Irish species, like the natterjack toad, in co-operation with the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

“Over the last number of years, we’ve released back about 7,000 young toads back into Kerry. It is something that we’re very passionate about,” explains Declan.

40 years of conservation

Fota Wildlife Park is celebrating their 40th anniversary this summer.

“We’re delighted it has come around and we’ve all survived through COVID-19,” reflects Declan.

“A lot of that was through the generosity of the people of Ireland and the people of Cork who have supported us over the years. Without them we can’t do it. At the end of the day, we depended on people coming to visit us to support the work that we’re doing.”

And it’s those visitors – in particular the younger ones – that make Declan’s job so rewarding.

“There’s just nothing like a child to ground you and ask questions,” he says.

“I think all of the staff that we have here are just as driven as myself and they want to be able to provide the answer. The depth of knowledge and experience that we have here is phenomenal.”

Read more

Lessons from India and Europe on co-operative farming

Meet the travel bursary students on tour

As animal care manager at Fota Wildlife Park, Declan O’Donovan is responsible for the 108 exotic species at the 100-acre park collection.

Yet, his love of nature did not start on the Serengeti or in the rainforest - it started on dairy farms.

Hailing from Bishopstown, Co Cork, Declan was exposed to the world of animal care from an early age as his father, Sean O’Donovan was a dairy science lecturer and farm manager for University College Cork (UCC).

“As I was growing up around the farm, I always had that special sort of attraction and affinity to animals,” he explains.

After the purchase of Fota Estate by UCC in 1976, Declan witnessed first-hand the transformation of Fota Estate over the years. In fact, he even remembers his father sitting at the kitchen table and drawing up plans for some of the houses for the initial animals coming in during the establishment of Fota Wildlife Park, in 1983.

Paving a pathway

When Declan finished school in the early 1980s, employment was scarce.

“When I left school, I was like many kids, all I wanted to do was leave. I had no desire to go to university,” he says.

As the wildlife park was setting up, however, they were looking for staff. Declan ended up working for Fota as an animal keeper in the early days, until 1988,when he left to go to university in the UK.

“I did a behavioural ecology degree. And from there I travelled around a little bit, I spent a year in Australia, where I worked in Perth Zoo as one of their keepers,” he explains.

After another stint in Ireland, Declan went to the Middle East, where he stayed for 23 years. During that time, he established a successful cheetah breeding programme at the Wadi Al Safa Wildlife Centre in Dubai.

In the last 20 years, amongst other notable achievements, this centre has bred over 90 critically endangered northern cheetahs, many of which have been sent to Europe to establish a core breeding population for the European Association Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA).

“[They] set up studbooks so that they ensure the correct animals go and breed with the correct animals so you maintain the genetic diversity of the population,” explains Declan.

“We were also involved with one of the bigger breeding facilities for cheetahs. We supplied a number of animals to breeding programmes here in Europe. Here in Fota, we still have two of those animals, which we sent over.”

Animal care manager

Due to a number of factors with family members getting older and his children going to university in Europe, Declan and his wife decided to return to Ireland.

Another major attraction to coming home for Declan was being offered the opportunity to be involved with native Irish wildlife conservation in Fota Wildlife Park as their animal care manager. This involves working with rangers and making sure that the welfare of animals is looked after.

“There were no issues beforehand, but we’re just putting some policies and procedures into place so that it can all be documented. And we can go back and we can see what works, or what doesn’t work,” he explains.

Speaking about the most rewarding part of his job, Declan tells Irish Country Living that he loves to see the passion that some of the younger rangers have for the animals they care for, while he also enjoys breeding particular species that he knows will go towards future release.

“Even if we’re just a reserve for animals that are needed later on, we’re happy to do that because we know that somebody needs to keep them and make sure they are safe and protected,” he explains.

Money from a conservation budget also contributes to different projects that Fota are involved in. This is part of their responsibilities in EAZA.

“We also support PhD students and undergraduate students in some of the research work that they do both here in the wildlife park, in UCC and at other universities,” he says.

For Declan, research is very valuable and he supports and encourages anybody in it as he believes that “it’s the only way we learn.”

Indeed, Declan himself conducted one of the earliest animal welfare research projects, which focused on the impact of visitors on the behaviour of captive cheetahs and their cubs.

He also holds a master’s degree in conservation biology, where he researched the physiological and morphometric features of the Arabian oryx. He is currently awaiting the defence of his PhD at UCC, which examined the use of translocation of a threatened, large terrestrial reptile species in the Emirate of Dubai.

Native species

The importance of Ireland’s native species, however, cannot be overlooked, as Declan emphasises.

“In a lot of cases, people mentioned the rainforest declining at certain rates and things, but you don’t have to go outside of Ireland to see the damage to very sensitive areas,” he says.

“Unless we start looking at trying to help and support what we have here in Ireland, then I think it’s a little bit hypocritical to a certain extent.”

Fota Wildlife Park is taking a leadership role in the conservation of native Irish species, like the natterjack toad, in co-operation with the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

“Over the last number of years, we’ve released back about 7,000 young toads back into Kerry. It is something that we’re very passionate about,” explains Declan.

40 years of conservation

Fota Wildlife Park is celebrating their 40th anniversary this summer.

“We’re delighted it has come around and we’ve all survived through COVID-19,” reflects Declan.

“A lot of that was through the generosity of the people of Ireland and the people of Cork who have supported us over the years. Without them we can’t do it. At the end of the day, we depended on people coming to visit us to support the work that we’re doing.”

And it’s those visitors – in particular the younger ones – that make Declan’s job so rewarding.

“There’s just nothing like a child to ground you and ask questions,” he says.

“I think all of the staff that we have here are just as driven as myself and they want to be able to provide the answer. The depth of knowledge and experience that we have here is phenomenal.”

Read more

Lessons from India and Europe on co-operative farming

Meet the travel bursary students on tour

SHARING OPTIONS