As herd sizes grow, making the transition from managing stock and working on your own, to employing people and delegating responsibility can be daunting.

One family with generations of experience of managing people are the Maxwells of Moore Hill, near Tallow, Co Waterford. When Shane Maxwell returned home to take over the family farms in 2001, he took over a sizeable business. The dairy farm at Lismore had a herd of 360 cows, while the home farm (seven miles away at Moore Hill) had a 900-acre tillage and 1,200-ewe sheep enterprise, alongside apple orchards and grain storage.

At the time the Maxwells were in partnership with the Jameson family. The Moore Hill farm was converted to dairy in 2009. Today, there is a total of 480ha farmed, with a combined milking platform of 300ha. Most of the land is owned. There are 930 cows being milked between the two farms, with 240 in-calf heifers, 240 maiden heifers and 60 bulls all being managed by the farm team.

At the head of this team is Esther Walsh. Esther started working for Shane in November 2005, having returned from a two-year stint managing farms in New Zealand, and is now about to head into her 12th spring managing Moore Hill Farms.

Both Shane and Esther are at pains to point out that they don’t think they have all the answers. They see themselves as being on a journey, constantly learning new and better ways of running the farm and managing people.

Shane is the farm owner, but is no longer involved in the day-to-day management. Esther is the farm manager, with overall responsibility for the stock and everything that goes on the farm. All employees report to her, while she in turn reports to Shane. After working together for the past 11 years, the relationship between the two is one of mutual trust.

In terms of the challenges of dairy farming, this farm has it all: large numbers of cows, multiple farm units and over 10 full-time employees. So what’s the system and how does it all work?

The original dairy farm at Lismore is a dedicated milking block of 134ha, with 420 cows going through a 50-bale Dairymaster rotary parlour. There is currently a vacancy for a herd manager on this farm. Whoever takes up this position will be responsible for the day-to-day running of the farm, with as much support from Esther as required.

Alongside the herd manager are two full-time employees with responsibility for milking, feeding and most of the fertiliser spreading.

The calves from both farms are reared until weaning in calf sheds at Lismore. Beesh and Lucas are two dedicated calf-rearers and they are based on the Lismore farm during calving. When the calves are weaned off milk, Beesh and Lucas follow them back to Moore Hill where all youngstock are reared on outfarms close to the dairy unit.

The youngstock spend their first and second winters in Moore Hill. All the heifers calve in Moore Hill and are milked through a 50-bale Milfos rotary parlour. Between the in-calf heifers and cows, 570 pregnant animals are housed in cubicle sheds in Moore Hill, while 400 cows are housed in Lismore.

There is 161ha in the milking platform at Moore Hill and as soon as 530 cows are calved, which is a stocking rate of 3.1 cows/ha, the remaining cows on the farm are all sent to Lismore.

With all the heifers calving in Moore Hill, the calving rate is very fast. The heifers are bred one week before the cows on 15 April, so calving starts in mid-January and usually by 5 March there are 530 cows calved and any remaining cows on the farm are moved to Lismore.

Cows are calved in straw-bedded sheds. As soon as a calf is born, she is given 3l of colostrum. A rubber tyre tube with a tag fixed to it is placed around the calf’s neck. The tag number of the tube and the tag number of the dam along with the gender of the calf, the time and date of birth, and the calving difficulty are recorded on a duplicate notebook.

The freshly-calved cow is then moved to the colostrum mob. Once or twice a day, the young calves are loaded onto a trailer and brought to Lismore, along with the duplicate copy of their calving details. Once they get to Lismore, they are tagged by a senior staff member and the neck band is sent back to Moore Hill to be used on another calf.

When the freshly-calved cows get to the parlour, their numbers are recorded and checked off against the calving book to make sure that the correct cow number was recorded. Coloured tape is placed on her tail. There are four different colours for different days of the week. After four days, cows with the same colour tape are CMT-tested and drafted from the colostrum group in to the main herd.

“It’s all about checks and balances. With big numbers of cows and a lot of people around, mistakes can easily happen. Checking the tag numbers of the freshly-calved cows as they come into the parlour and cross-referencing them against the calving book is a big help in avoiding mistakes. Sometimes people read can numbers the wrong way around when they’re busy, so double-checking avoids that,” Esther says.

As you can imagine, things are pretty hectic in Moore Hill during this period. For the first four weeks or so, or until the heifers settle down, the herd is only milked once a day. Esther and two others are in the milking parlour every morning during the spring.

Brendan Daly is the dedicated night calver during the spring. He works on the farm all-year round, but covers a night shift in spring. His working day starts at 8:30pm and finishes up at 5:30am. He checks the calvings in both farms, moves newborn calves to Lismore and does other jobs if calving is quiet, such as bringing the milking cows into the collecting yard before the main team arrive at 5:30am.

A first-year student of the professional diploma in dairy farm management is employed every year. Jason Melbourne is this year’s student. He started in September and will be on the farm for a year, while spending a couple of days per month at lectures in Moorepark.

Jason works closely with Esther. They do most of the grass walks at Moore Hill together, but Jason has already started to do a few grass walks on his own. He is effectively a second-in-charge for Esther, making decisions about when cows need to move to a next paddock and so forth. He lives on the farm and will move the herd on after a few hours’ grazing in the evening if he thinks they didn’t clean it out properly during the day.

“I love it when they hit the residual without hitting the bulk tank – even though I probably shouldn’t be looking at the bulk tank,” he says.

There are three full-time employees in Moore Hill over the summer, with Esther floating between both farms. The main jobs at Moore Hill are managing the cows and youngstock, feeding the herd over winter and spreading some of the fertiliser. The farms have their own sets of machinery, which are the same for both: a JCB loader, a 120hp New Holland tractor, a Keenan diet feeder and a shared fertiliser spreader.

The Maxwell herd is one of the finest in the country. Shane’s father, John, travelled to New Zealand with the late Paddy O’Keeffe and others in 1963 and again in 1972. Many of the lessons from these study trips have been implemented on the Maxwell farm. The Jersey crossbred herd is within the top 60 highest EBI herds in the country with an EBI of €133, a milk sub index of €33 and a fertility sub-index of €57.

Between the two herds, they are on track to produce 450kg of milk solids per cow or 1,350kg MS/ha this year from around 650kg of meal per cow. The empty rate this year was 8% after 12 weeks of breeding. Average grass growth between the two farms is 14.65t/ha.

In the busy period from mid-January right through to the end of the third week of AI in mid-May, the roster is 12 days on and two days off, so every second weekend is off. After that, the roster changes to 10 days on and four days off, which means that every second weekend is worked followed by a four-day weekend with Friday and Monday off.

The roster is in the farm office for everyone to see. Everyone knows in advance when it’s their weekend off and that never really changes unless they need to swap with someone else. This means that everyone on the farm can plan ahead.

Brendan, who does the night calvings, works six nights on and one night off during calving. He is covered by a relief nightwatchman. The staff also rotate who is to stay later in the evening until Brendan arrives at 8:30pm. This means there is always somebody on-farm during calving.

“Never mind the animal welfare side of it, the organisational benefits of having somebody on the farm to identify and snatch calves is massive. We would regularly calve 15 or 20 cows a night, so it would be mayhem in the mornings if we didn’t have someone on during the night,” Esther says.

The normal hours of work for farm staff are from 5:30am to 5pm during the spring. However, Esther regularly puts in much longer hours herself in spring.

“It’s very seldom that the farm staff are on the farm after 5pm and that’s the way I like it. I’m always conscious about making that happen. We expect people to be on the farm for a certain time in the morning so it’s important they get to go home at a certain time.

“The biggest difference between a large herd and a small herd is that moving cows takes up so much more time. It takes an hour and a half to get the cows in for milking in the summer, but longer in autumn. This means that someone has to go for cows at 1:30pm and this in turn means that that person has to go for his or her lunch at 12:30pm.

“So, if we’re doing a job like dosing calves or spreading fertiliser, they need to get away early or else everyone on the farm will be staying late,” Esther says.

During the mid-season and autumn, the two farms can operate with a skeleton staff of four people in the mornings and three people in the evenings. Saturdays and Sundays are days where only the routine jobs are done.

There are no automatic cluster removers on the parlour in Lismore so two people always milk there. I asked Shane why he wouldn’t install ACRs.

“We have thought about it, but at the end of the day I’m not sure if we would save much time or labour. At 420 cows, it’s always a two-person farm. Leaving aside the cost of them, ACRs won’t bring in the cows or wash the yards after milking.”

In Moore Hill, two people are on the farm in the mornings. At the weekends this is often an experienced employee and a relief milker. The experienced person will get the cows in and get milking started, before going off and checking the youngstock. When they get back to the yard, they bring in the second herd and then stay to wash up. Only one person milks in the evening because they have ACRs in that parlour and only one herd is milked and the youngstock don’t need to be checked.

The milkers on both farms operate in teams of two. At the moment in Moore Hill, Jason and Beesh do most of the milkings together during the week. One starts at 5:30am by bringing in the cows, while the other person starts at 7am. Whoever starts early gets to go home at 3pm, when the cows are in the yard for the evening milking.

Esther’s plan is that on the Thursday before their weekend off, they should finish up at 3pm and start back at 7am on the following Tuesday. Esther says this doesn’t always work out, but she is trying to better integrate the start times into the roster.

There is an acceptance among everyone working on the farm that spring is a busy time of year. In between calving and the start of mating, everyone working on the farm gets five days’ holidays plus the weekend off, so seven days off in a row.

There is a five-week window for everyone to take their time off, and Esther allocates a week to everyone before taking time off herself. Staff in Lismore get the same amount of time off, but because they calve a bit later and don’t have heifers to breed, they take their holidays a bit later.

During the calving and breeding seasons, Esther is on both farms almost every day. While she lives close to the Lismore farm, she spends more time in Moore Hill because there are more things going on there, with the younger herd and all the youngstock. Things are more straightforward in Lismore, with older cows and no grazing youngstock.

The two milking blocks are walked every five days from May through to August, when grass is growing fastest. Outside of this period they are walked once a week along with the youngstock blocks. Esther and Jason do all the grass measuring and make decisions based on growth and farm cover relative to targets and the grass budget.

Routine jobs such as dosing or vaccinating takes extra organising due to the sheer numbers involved. Esther refers back to the roster when picking the days to do the jobs, to make sure there are sufficient staff on hand and that they know the plan in advance. Between days off and holidays, there aren’t many days during the summer where the full team are in.

After the spring and the first three weeks of breeding, Esther’s and the team’s workload eases dramatically. At this stage in the year, she goes back to a five-day week, while the farm staff work the 10-day on and four day-off roster.

Generally speaking, she doesn’t roster herself into the milking rota during the mid-season and autumn, but there will be times when she is needed to fall in. She takes 18 days of holidays every July.

While Shane isn’t hands-on at farm work, he does provide a layer of oversight over the whole operation. Key things he looks out for are grass covers, fat and protein percentages, SCC, fertility performance, time sheets and the number of evening milkings Esther does during the summer.

For Shane, these are indicators as to how well the farm is operating.

“When I get the time sheets, the first thing I look out for is how many days the guys are working past 5pm. If this is routinely happening, we need to ask ourselves why. Sometimes it’s their fault for not going for the cows in time, but I need to make sure it’s not as a result of something myself and Esther are doing. Similarly, if Esther is doing too many evening milkings, it means we are short staff,” Shane says.

He also spends a lot of time doing budgets and reviewing financial performance.

As for SCC, when I visited in late October, the Moore Hill herd had an SCC of 77,000, while the Lismore herd had an SCC of 87,000. The farm was in the top 500 farms in the country for SCC over the last three years.

Shane employs a local bookkeeper to keep track of invoices and payroll, including PAYE and PRSI. Shane approves the payment of invoices once a month and most are paid electronically. Most staff are paid weekly by direct debit, while Esther is paid monthly. The bookkeeper does about 20 hours per month.

In 2015, labour costs on the farm were 7.54c/l, including €15,000 for Shane’s own labour.

There are two paths of communication at Moore Hill Farms. The first is between Esther and Shane. They chat frequently depending on the time of the year and what’s happening on the farm. When things are going smoothly, this might just be a quick chat on the phone. They also have more structured monthly meetings, where they discuss more strategic things such as grass budgets, fertiliser plans, breeding plans, capital expenditure and look ahead to the next few months.

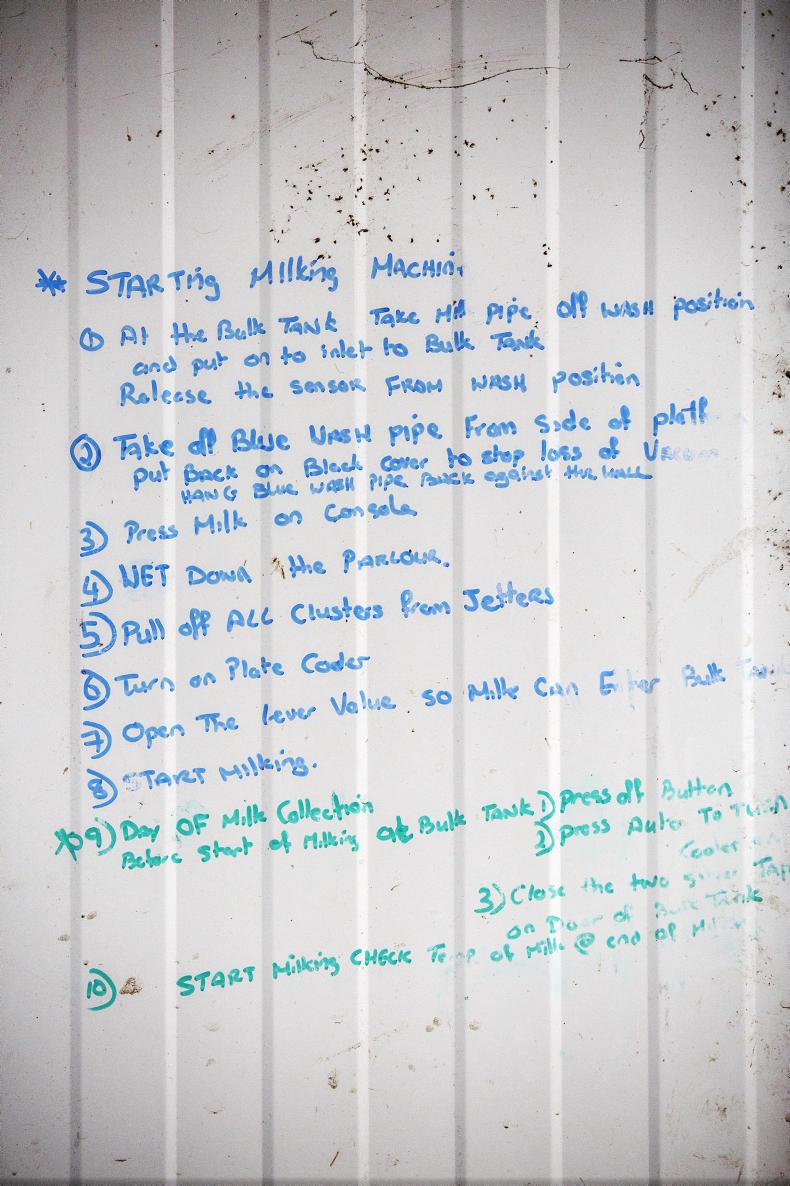

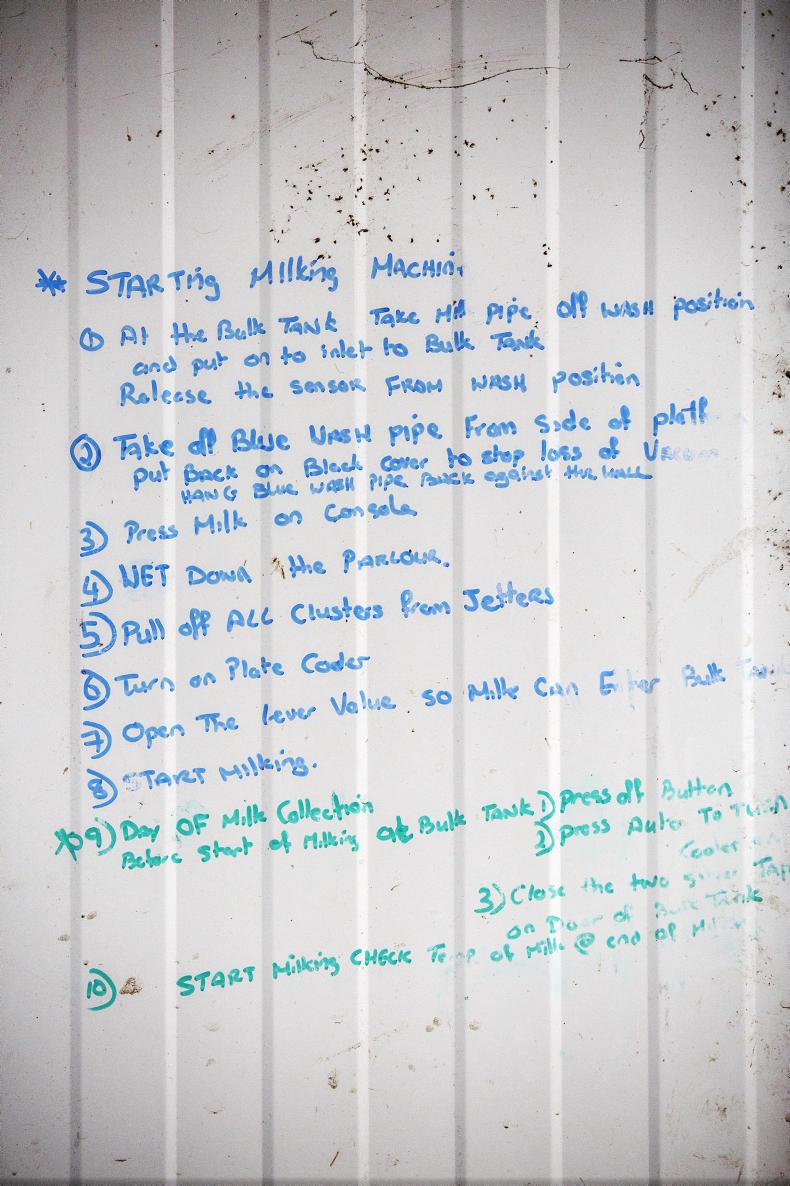

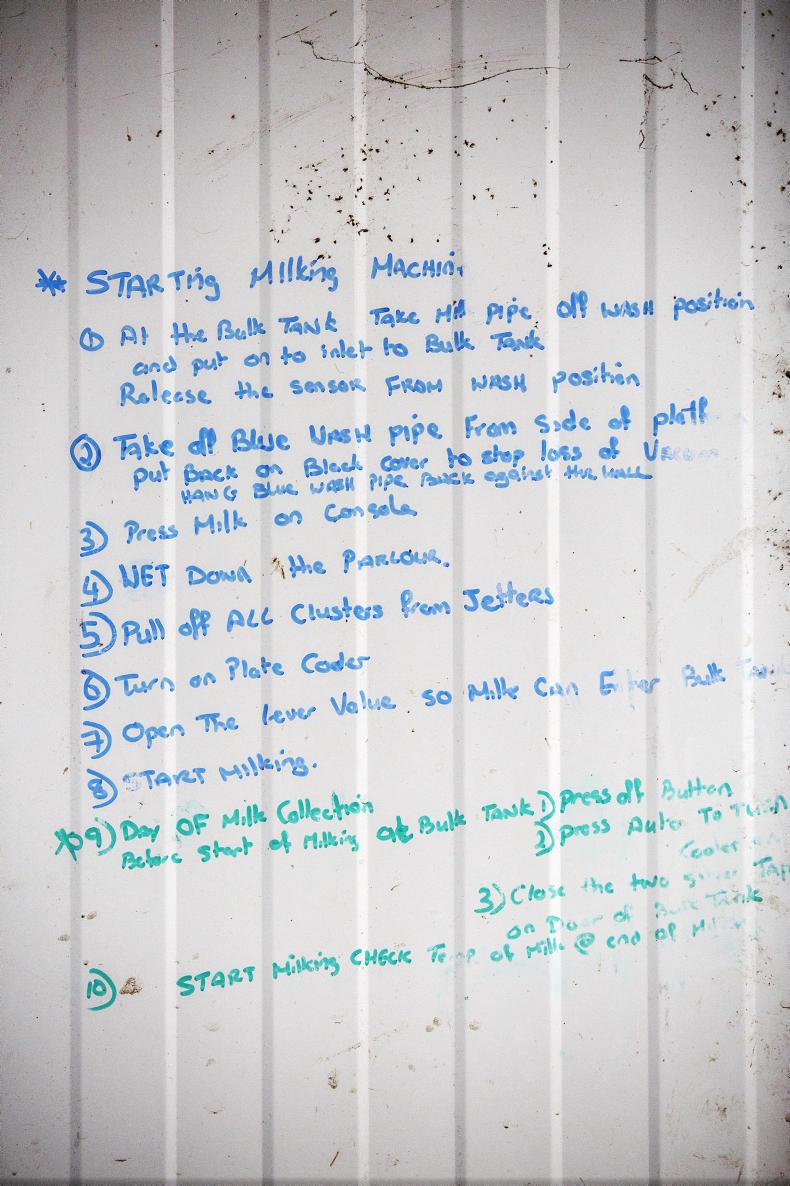

The next is between Esther and the farm staff. English is not the first language for many of the staff, so Esther’s communication skills need to be good to get the message across. She is a big believer in writing up protocols and standard operating procedures. Every switch and handle in the milking parlour is labelled, and there is a myriad of whiteboards around the dairy and farm office detailing how everything operates.

She normally has four team meetings a year, where all the staff come together in the farm office and they discuss topical subjects for the time of year. In spring, this could be the procedure for calving and feeding calves; and coming up to breeding, it would be about spotting cows in heat and so forth.

“I think the staff were a bit nervous coming into the first one. They didn’t really know what to expect, but after a while they began to enjoy them. The more they learn, the more responsibility they get and the more they enjoy their job,” Esther says.

Shane thinks there is still a lot more they can do to improve communication: “We need to make it second nature to us rather than being an effort. It’s important for the overall culture within the business. I have lots of ideas on communication, but I am not always the best at communicating them.”

They also celebrate success, going for nights out at the end of calving, having a summer barbecue and a Christmas party.

While readily admitting that they don’t have all the answers, it’s hard to find fault with the way people are managed at Moore Hill Farms. The practices adopted by Shane and Esther set an example to everyone, not just large farmers. It’s all about balance; the busy spring is balanced by a week off before breeding and the busy breeding period is balanced with a 10-on and four-off roster after the first three weeks are over. Making this roster work takes planning and organising on Esther’s behalf, but she does it and does it well.

Labour costs, at 7.54c/l last year, are not exorbitant and show that you can treat staff well, with good time off without costing a fortune. Productivity is high. Good people, well looked after are an asset, not a cost.

Read more

Listen: 6,000 dairy workers wanted

Long term plan needed to solve labour shortage

As herd sizes grow, making the transition from managing stock and working on your own, to employing people and delegating responsibility can be daunting.

One family with generations of experience of managing people are the Maxwells of Moore Hill, near Tallow, Co Waterford. When Shane Maxwell returned home to take over the family farms in 2001, he took over a sizeable business. The dairy farm at Lismore had a herd of 360 cows, while the home farm (seven miles away at Moore Hill) had a 900-acre tillage and 1,200-ewe sheep enterprise, alongside apple orchards and grain storage.

At the time the Maxwells were in partnership with the Jameson family. The Moore Hill farm was converted to dairy in 2009. Today, there is a total of 480ha farmed, with a combined milking platform of 300ha. Most of the land is owned. There are 930 cows being milked between the two farms, with 240 in-calf heifers, 240 maiden heifers and 60 bulls all being managed by the farm team.

At the head of this team is Esther Walsh. Esther started working for Shane in November 2005, having returned from a two-year stint managing farms in New Zealand, and is now about to head into her 12th spring managing Moore Hill Farms.

Both Shane and Esther are at pains to point out that they don’t think they have all the answers. They see themselves as being on a journey, constantly learning new and better ways of running the farm and managing people.

Shane is the farm owner, but is no longer involved in the day-to-day management. Esther is the farm manager, with overall responsibility for the stock and everything that goes on the farm. All employees report to her, while she in turn reports to Shane. After working together for the past 11 years, the relationship between the two is one of mutual trust.

In terms of the challenges of dairy farming, this farm has it all: large numbers of cows, multiple farm units and over 10 full-time employees. So what’s the system and how does it all work?

The original dairy farm at Lismore is a dedicated milking block of 134ha, with 420 cows going through a 50-bale Dairymaster rotary parlour. There is currently a vacancy for a herd manager on this farm. Whoever takes up this position will be responsible for the day-to-day running of the farm, with as much support from Esther as required.

Alongside the herd manager are two full-time employees with responsibility for milking, feeding and most of the fertiliser spreading.

The calves from both farms are reared until weaning in calf sheds at Lismore. Beesh and Lucas are two dedicated calf-rearers and they are based on the Lismore farm during calving. When the calves are weaned off milk, Beesh and Lucas follow them back to Moore Hill where all youngstock are reared on outfarms close to the dairy unit.

The youngstock spend their first and second winters in Moore Hill. All the heifers calve in Moore Hill and are milked through a 50-bale Milfos rotary parlour. Between the in-calf heifers and cows, 570 pregnant animals are housed in cubicle sheds in Moore Hill, while 400 cows are housed in Lismore.

There is 161ha in the milking platform at Moore Hill and as soon as 530 cows are calved, which is a stocking rate of 3.1 cows/ha, the remaining cows on the farm are all sent to Lismore.

With all the heifers calving in Moore Hill, the calving rate is very fast. The heifers are bred one week before the cows on 15 April, so calving starts in mid-January and usually by 5 March there are 530 cows calved and any remaining cows on the farm are moved to Lismore.

Cows are calved in straw-bedded sheds. As soon as a calf is born, she is given 3l of colostrum. A rubber tyre tube with a tag fixed to it is placed around the calf’s neck. The tag number of the tube and the tag number of the dam along with the gender of the calf, the time and date of birth, and the calving difficulty are recorded on a duplicate notebook.

The freshly-calved cow is then moved to the colostrum mob. Once or twice a day, the young calves are loaded onto a trailer and brought to Lismore, along with the duplicate copy of their calving details. Once they get to Lismore, they are tagged by a senior staff member and the neck band is sent back to Moore Hill to be used on another calf.

When the freshly-calved cows get to the parlour, their numbers are recorded and checked off against the calving book to make sure that the correct cow number was recorded. Coloured tape is placed on her tail. There are four different colours for different days of the week. After four days, cows with the same colour tape are CMT-tested and drafted from the colostrum group in to the main herd.

“It’s all about checks and balances. With big numbers of cows and a lot of people around, mistakes can easily happen. Checking the tag numbers of the freshly-calved cows as they come into the parlour and cross-referencing them against the calving book is a big help in avoiding mistakes. Sometimes people read can numbers the wrong way around when they’re busy, so double-checking avoids that,” Esther says.

As you can imagine, things are pretty hectic in Moore Hill during this period. For the first four weeks or so, or until the heifers settle down, the herd is only milked once a day. Esther and two others are in the milking parlour every morning during the spring.

Brendan Daly is the dedicated night calver during the spring. He works on the farm all-year round, but covers a night shift in spring. His working day starts at 8:30pm and finishes up at 5:30am. He checks the calvings in both farms, moves newborn calves to Lismore and does other jobs if calving is quiet, such as bringing the milking cows into the collecting yard before the main team arrive at 5:30am.

A first-year student of the professional diploma in dairy farm management is employed every year. Jason Melbourne is this year’s student. He started in September and will be on the farm for a year, while spending a couple of days per month at lectures in Moorepark.

Jason works closely with Esther. They do most of the grass walks at Moore Hill together, but Jason has already started to do a few grass walks on his own. He is effectively a second-in-charge for Esther, making decisions about when cows need to move to a next paddock and so forth. He lives on the farm and will move the herd on after a few hours’ grazing in the evening if he thinks they didn’t clean it out properly during the day.

“I love it when they hit the residual without hitting the bulk tank – even though I probably shouldn’t be looking at the bulk tank,” he says.

There are three full-time employees in Moore Hill over the summer, with Esther floating between both farms. The main jobs at Moore Hill are managing the cows and youngstock, feeding the herd over winter and spreading some of the fertiliser. The farms have their own sets of machinery, which are the same for both: a JCB loader, a 120hp New Holland tractor, a Keenan diet feeder and a shared fertiliser spreader.

The Maxwell herd is one of the finest in the country. Shane’s father, John, travelled to New Zealand with the late Paddy O’Keeffe and others in 1963 and again in 1972. Many of the lessons from these study trips have been implemented on the Maxwell farm. The Jersey crossbred herd is within the top 60 highest EBI herds in the country with an EBI of €133, a milk sub index of €33 and a fertility sub-index of €57.

Between the two herds, they are on track to produce 450kg of milk solids per cow or 1,350kg MS/ha this year from around 650kg of meal per cow. The empty rate this year was 8% after 12 weeks of breeding. Average grass growth between the two farms is 14.65t/ha.

In the busy period from mid-January right through to the end of the third week of AI in mid-May, the roster is 12 days on and two days off, so every second weekend is off. After that, the roster changes to 10 days on and four days off, which means that every second weekend is worked followed by a four-day weekend with Friday and Monday off.

The roster is in the farm office for everyone to see. Everyone knows in advance when it’s their weekend off and that never really changes unless they need to swap with someone else. This means that everyone on the farm can plan ahead.

Brendan, who does the night calvings, works six nights on and one night off during calving. He is covered by a relief nightwatchman. The staff also rotate who is to stay later in the evening until Brendan arrives at 8:30pm. This means there is always somebody on-farm during calving.

“Never mind the animal welfare side of it, the organisational benefits of having somebody on the farm to identify and snatch calves is massive. We would regularly calve 15 or 20 cows a night, so it would be mayhem in the mornings if we didn’t have someone on during the night,” Esther says.

The normal hours of work for farm staff are from 5:30am to 5pm during the spring. However, Esther regularly puts in much longer hours herself in spring.

“It’s very seldom that the farm staff are on the farm after 5pm and that’s the way I like it. I’m always conscious about making that happen. We expect people to be on the farm for a certain time in the morning so it’s important they get to go home at a certain time.

“The biggest difference between a large herd and a small herd is that moving cows takes up so much more time. It takes an hour and a half to get the cows in for milking in the summer, but longer in autumn. This means that someone has to go for cows at 1:30pm and this in turn means that that person has to go for his or her lunch at 12:30pm.

“So, if we’re doing a job like dosing calves or spreading fertiliser, they need to get away early or else everyone on the farm will be staying late,” Esther says.

During the mid-season and autumn, the two farms can operate with a skeleton staff of four people in the mornings and three people in the evenings. Saturdays and Sundays are days where only the routine jobs are done.

There are no automatic cluster removers on the parlour in Lismore so two people always milk there. I asked Shane why he wouldn’t install ACRs.

“We have thought about it, but at the end of the day I’m not sure if we would save much time or labour. At 420 cows, it’s always a two-person farm. Leaving aside the cost of them, ACRs won’t bring in the cows or wash the yards after milking.”

In Moore Hill, two people are on the farm in the mornings. At the weekends this is often an experienced employee and a relief milker. The experienced person will get the cows in and get milking started, before going off and checking the youngstock. When they get back to the yard, they bring in the second herd and then stay to wash up. Only one person milks in the evening because they have ACRs in that parlour and only one herd is milked and the youngstock don’t need to be checked.

The milkers on both farms operate in teams of two. At the moment in Moore Hill, Jason and Beesh do most of the milkings together during the week. One starts at 5:30am by bringing in the cows, while the other person starts at 7am. Whoever starts early gets to go home at 3pm, when the cows are in the yard for the evening milking.

Esther’s plan is that on the Thursday before their weekend off, they should finish up at 3pm and start back at 7am on the following Tuesday. Esther says this doesn’t always work out, but she is trying to better integrate the start times into the roster.

There is an acceptance among everyone working on the farm that spring is a busy time of year. In between calving and the start of mating, everyone working on the farm gets five days’ holidays plus the weekend off, so seven days off in a row.

There is a five-week window for everyone to take their time off, and Esther allocates a week to everyone before taking time off herself. Staff in Lismore get the same amount of time off, but because they calve a bit later and don’t have heifers to breed, they take their holidays a bit later.

During the calving and breeding seasons, Esther is on both farms almost every day. While she lives close to the Lismore farm, she spends more time in Moore Hill because there are more things going on there, with the younger herd and all the youngstock. Things are more straightforward in Lismore, with older cows and no grazing youngstock.

The two milking blocks are walked every five days from May through to August, when grass is growing fastest. Outside of this period they are walked once a week along with the youngstock blocks. Esther and Jason do all the grass measuring and make decisions based on growth and farm cover relative to targets and the grass budget.

Routine jobs such as dosing or vaccinating takes extra organising due to the sheer numbers involved. Esther refers back to the roster when picking the days to do the jobs, to make sure there are sufficient staff on hand and that they know the plan in advance. Between days off and holidays, there aren’t many days during the summer where the full team are in.

After the spring and the first three weeks of breeding, Esther’s and the team’s workload eases dramatically. At this stage in the year, she goes back to a five-day week, while the farm staff work the 10-day on and four day-off roster.

Generally speaking, she doesn’t roster herself into the milking rota during the mid-season and autumn, but there will be times when she is needed to fall in. She takes 18 days of holidays every July.

While Shane isn’t hands-on at farm work, he does provide a layer of oversight over the whole operation. Key things he looks out for are grass covers, fat and protein percentages, SCC, fertility performance, time sheets and the number of evening milkings Esther does during the summer.

For Shane, these are indicators as to how well the farm is operating.

“When I get the time sheets, the first thing I look out for is how many days the guys are working past 5pm. If this is routinely happening, we need to ask ourselves why. Sometimes it’s their fault for not going for the cows in time, but I need to make sure it’s not as a result of something myself and Esther are doing. Similarly, if Esther is doing too many evening milkings, it means we are short staff,” Shane says.

He also spends a lot of time doing budgets and reviewing financial performance.

As for SCC, when I visited in late October, the Moore Hill herd had an SCC of 77,000, while the Lismore herd had an SCC of 87,000. The farm was in the top 500 farms in the country for SCC over the last three years.

Shane employs a local bookkeeper to keep track of invoices and payroll, including PAYE and PRSI. Shane approves the payment of invoices once a month and most are paid electronically. Most staff are paid weekly by direct debit, while Esther is paid monthly. The bookkeeper does about 20 hours per month.

In 2015, labour costs on the farm were 7.54c/l, including €15,000 for Shane’s own labour.

There are two paths of communication at Moore Hill Farms. The first is between Esther and Shane. They chat frequently depending on the time of the year and what’s happening on the farm. When things are going smoothly, this might just be a quick chat on the phone. They also have more structured monthly meetings, where they discuss more strategic things such as grass budgets, fertiliser plans, breeding plans, capital expenditure and look ahead to the next few months.

The next is between Esther and the farm staff. English is not the first language for many of the staff, so Esther’s communication skills need to be good to get the message across. She is a big believer in writing up protocols and standard operating procedures. Every switch and handle in the milking parlour is labelled, and there is a myriad of whiteboards around the dairy and farm office detailing how everything operates.

She normally has four team meetings a year, where all the staff come together in the farm office and they discuss topical subjects for the time of year. In spring, this could be the procedure for calving and feeding calves; and coming up to breeding, it would be about spotting cows in heat and so forth.

“I think the staff were a bit nervous coming into the first one. They didn’t really know what to expect, but after a while they began to enjoy them. The more they learn, the more responsibility they get and the more they enjoy their job,” Esther says.

Shane thinks there is still a lot more they can do to improve communication: “We need to make it second nature to us rather than being an effort. It’s important for the overall culture within the business. I have lots of ideas on communication, but I am not always the best at communicating them.”

They also celebrate success, going for nights out at the end of calving, having a summer barbecue and a Christmas party.

While readily admitting that they don’t have all the answers, it’s hard to find fault with the way people are managed at Moore Hill Farms. The practices adopted by Shane and Esther set an example to everyone, not just large farmers. It’s all about balance; the busy spring is balanced by a week off before breeding and the busy breeding period is balanced with a 10-on and four-off roster after the first three weeks are over. Making this roster work takes planning and organising on Esther’s behalf, but she does it and does it well.

Labour costs, at 7.54c/l last year, are not exorbitant and show that you can treat staff well, with good time off without costing a fortune. Productivity is high. Good people, well looked after are an asset, not a cost.

Read more

Listen: 6,000 dairy workers wanted

Long term plan needed to solve labour shortage

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: