The latest results from the Teagasc on-farm grass variety work were released last week. Single grass varieties (monocultures) were sown in full paddocks on 68 commercial dairy farms since 2011. Growth rate, number of grazings, number of silage cuts and post-grazing heights were recorded for each of the varieties on each of the farms.

Evaluating grass varieties on farms is a big step forward. The vast majority of research trials on grass varieties are done on small research plots and, while grazing can be simulated with more frequent cutting, nothing beats the true test of a real field situation.

Varieties on farms get exposed to a lot more than they do in a plot; different management, poaching, different pre- and post-grazing heights and generally more stress.

The farmers chosen for the study are from all over Ireland and farming on different soil types. The one common denominator is that they are all good grassland managers. They had to be consistently doing at least 30 grass measurements a year before getting involved in the study.

Each farm started off with four grass varieties, which were sown randomly on different paddocks of the milking platform. Every farm got Tyrella as one of the varieties, so this was the control.

Other than that, the seeds went in and they were managed as normal like every other paddock on the farm. New varieties were included in the study every year. Eleven varieties, some tetraploid (T) and some diploid (D), have been analysed over four years from 2013 to 2016. On top of the production type traits being analysed, ground score, ground score change over time and quality are being recorded too. The varieties used in the four-year study were: Aberchoice (D), AberGain (T), AberMagic (D), Astonenergy (T), Drumbo (D), Dunluce (T), Glenveagh (D), Kintyre (T), Majestic (D), Twymax (T) and Tyrella (D).

Results

In terms of total dry matter production (grazing and silage), there was a 1.6t/ha difference between the top and bottom varieties. Abermagic had the highest total growth averaged over the four years at 13.6t/ha, followed by Abergain at 13.5t/ha. At the other end of the scale, the lowest-growing varieties were Glenveagh and Majestic at 12t/ha.

But total dry matter production on its own is not a great way to assess a variety. Varieties sown on the milking platform are primarily used for grazing. Looking at the varieties that performed best for grazing is a really good indicator of how good a variety is. Or to look at it another way, varieties that are regularly closed for silage tend not to be good for grazing. Silage includes heavy cuts, but also light cuts of surplus grass.

The top-performing varieties here were Aberchoice, Abergain, Abermagic, Astonenergy and Drumbo, which produced over 12t/ha on average from grazing alone.

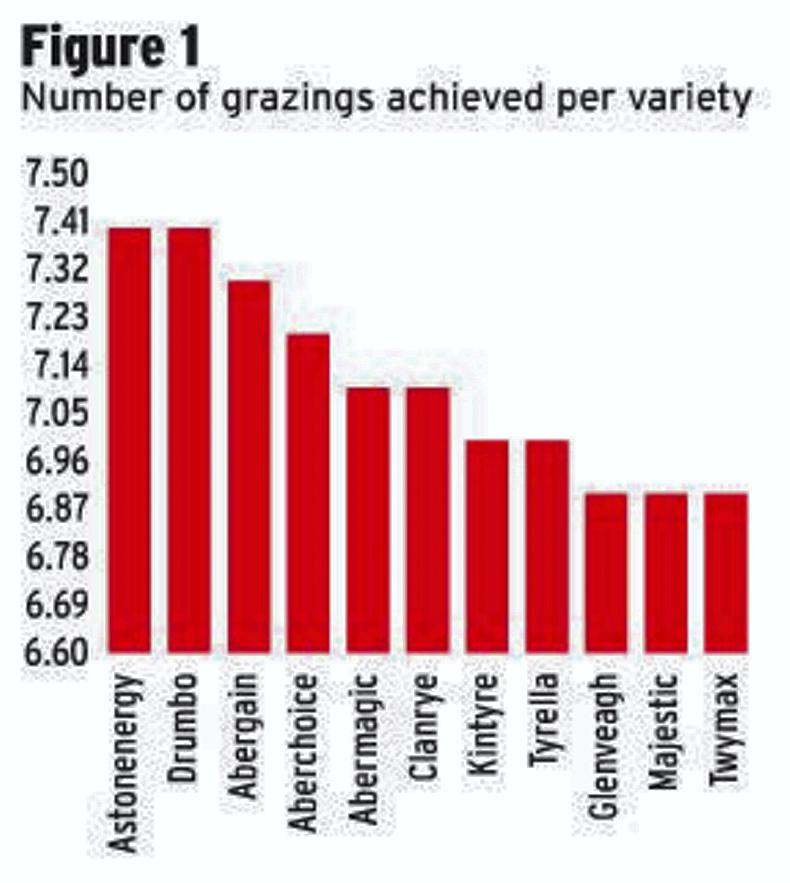

Looking at the number of grazings is another really good indicator of a variety and it ties in with grazing yield. Paddocks that are grazed often grow more and tend to be better quality. If cows didn’t like grazing it or if it wasn’t grazed out, it would be more likely to be closed for silage more often.

Figure 1 shows the number of grazings achieved. Astonenergy and Drumbo were the two varieties that were grazed most often, at 7.4 grazings per year on average. Glenveagh, Majestic and Twymax were grazed less often at 6.9 times per year.

When it comes to just spring growth, Abergain had the highest at 930kg/ha, while Glenveagh had the lowest at 750kg/ha. There was a 1.4t/ha difference in mid-season growth between the varieties. Abermagic and Abergain top the list at 7.6t/ha, while Majestic grew 6.2t/ha over the same period.

Quality

Pre-grazing grass samples were analysed for percentage of dry matter digestibility (DMD). Aberchoice scored highest at 85.5% DMD, followed by Astonenergy at 84% DMD. The remaining varieties have similar DMD, but Glenveagh was lowest at 81.1%.

Another indicator of variety performance is post-grazing sward height. Cows will graze out leafy swards that they like much easier than swards that they don’t like or that are stemmy. Post-grazing height was measured in 2016.

Astonenergy had the lowest post-grazing height of 4.1cm. The variety Clanrye, which was added to the study in 2015, had the highest post-grazing height at 5.2cm. Abergain and Aberchoice had a post-grazing height of 4.4cm and 4.5cm respectively.

Astonenergy had the lowest post-grazing height of 4.1cm. The variety Clanrye, which was added to the study in 2015, had the highest post-grazing height at 5.2cm. Abergain and Aberchoice had a post-grazing height of 4.4cm and 4.5cm respectively.

Ground score was measured on a scale of one to nine. The variety with the highest ground score was Glenveagh with a ground score of 4.3. Aston Energy had the lowest ground score at 3.7. Interestingly, the tetraploid Abergain had the second-highest ground score at 4.2.

On ground score change, Nicky Byrne, who is doing his PhD on the results collected, says the varieties with the highest ground score had the highest rate of decline over time, as they had more to lose. He says ground score change is a better indicator of persistency than just ground score.

Analysis

Table 1 ranks varieties for dry matter production, quality, the number of grazings and ground score. The first thing to question is the relevance of ground score as a selection criteria. We have known for some time that there is a direct negative correlation between ground score and quality. As ground score increases, quality decreases.

In this study, Glenveagh has the highest ground score, but performs the worst for production, quality and gets one of the least number of grazings. On the flip side, Astonenergy has the lowest ground score, but performs exceptionally well in all other areas.

The debate around ground score feeds into the tetraploid versus diploid debate. Generally speaking, tetraploids have lower ground scores than diploids. For this reason, farmers who view ground score as an important trait tend to avoid tetraploids or only include them at a low rate in seed mixes. But is this correct? The argument is often made that quality is of no use if you can’t graze the field because of the risk of poaching. While this is true, cow behaviour is also a factor in reducing poaching. Brendan Hinchion, one of the farmers in the study who farms heavy land in west/mid-Cork, gives his experience of grazing tetraploids and diploids:

“If you give a child a dinner they don’t like, they will play with the food, make a mess and eat very little of it. If you give them a dinner that they like, they will eat it all instantly and be happy.

“It’s the same with cows and tetraploids. If they like the grass, they will keep their heads down and graze it all in a few hours without doing damage, even if it is open and ground is wet. But if they don’t like the grass they will walk around and make a mess, even if ground cover is good. In general and although there are differences within the ploidy groups, there are way more advantages to tetraploids than diploids.”

Looking at these results, a number of grass varieties stand out as being very good all-rounders. These are Astonenergy and Abergain, both tetraploids, and Aberchoice, a diploid. These varieties achieve a good balance between growth, quality and number of grazings.

A common denominator of these three varieties is that they have very high figures for quality on the Pasture Profit Index (PPI) and the recommended list, which is reflected in the high number of grazings they achieve.

Farmers would have to ask themselves why they are diluting these good traits by allowing inferior varieties to be used in seed mixes.

The next step for Teagasc is to include more varieties in the on-farm evaluation and to feed this data into the PPI. The plan is to have all varieties on the Department of Agriculture recommended list in on-farm evaluation by next year.

SHARING OPTIONS