Ireland’s nitrates derogation provides farmers an opportunity to farm at higher stocking rates when they take extra steps to protect the environment. In effect, a farmer must not exceed a stocking rate of two dairy cows per hectare without a derogation. However, they can farm at 2.7LU/ha if approved for a derogation. The derogation is available to grassland farmers on an individual basis.

The key change coming in the current nitrate debacle will see the threshold for a derogation lowered to 220kg of organic nitrogen per hectare. This, along with other proposed changes, effectively means the allowed stocking rate on a 40ha farm will reduce from 118 cows to a 96 cows. This has huge implications for the viability of dairy farm businesses.

So why is this change important? It means a farmer who is doing everything right in terms of slurry storage, nutrient use, incorporating clover and managing nutrient runoff is capped at a low level on the number of cows he or she can milk on their holding.

The Irish dairy system has built its success on grass-based farming where feed is grown and harvested on the land where cows are held. Far too often, professionals use the word ‘intensive’ in an Irish context meaning stocked between 2.5 and 3.0 cows/ha. Let’s be clear – in some parts of Europe and elsewhere there are 1,000 cows on 10ha, the equivalent of 100 cows/ha. That’s intensive. Feed and water are brought from all corners of the world to feed animals.

Irish farmers are unique in Europe with our seasonal grass-based system of production matching grass growth patterns. Up to now, the permitted stocking rates have allowed this continue. The irony of lowering the stocking rate is it could push Irish farmers down a higher yield per cow road that threatens to release more carbon and push farmers into more purchased feeds.

The red tape for some landowners who traditionally have taken in nutrients from other farmers will prevent them accepting these nutrients in the future

Why? Land is the limiting factor. If a cow at 6,500l is classified as producing 106kg of organic nitrogen she might as well be producing 10,000l.

A farm family needs a certain volume of milk to dilute fixed and variable costs and provide a viable income and opportunity for succession.

What will be the knock-on impact of the proposed changes? The changes mean exporting nutrients off farm will become much more restricted. The red tape for some landowners who traditionally have taken in nutrients from other farmers will prevent them accepting these nutrients in the future. These non-dairy land owners could turn to more purchased artificial nutrients instead.

Land available to purchase, lease or rent will rise in value. The profitability of dairy will squeeze other enterprises out of existence. Indeed, this is already happening.

So what’s the state of play and what can the Department do? Firstly, the derogation is in place until 2025. However, a review is scheduled for September 2023. The water quality results to be used in that review are effectively gathered already (to the end of 2022). The raft of changes already imposed and changes coming next year in the continuing tightening of derogation rules will not get a chance to deliver any benefit to our waterways.

Secondly, using two years of water data in isolation for the review seems nonsensical from a scientific point of view. There are significant effects that could jeopardise the measurement integrity.

Thirdly, the mechanics of what I term the “Irish factor” on how milk is produced on this island must be further reinforced and understood at European level. This lies squarely with our Department officials. In addition, rural politicians need to understand what is at play and make their voices heard. Farm organisations must stand united on this. It has become crystal clear the consultation process with farm organisations failed to fully reveal the stocking rate reduction that was on the cards.

Farmers will, or at least should have, no problem with many of the proposed positive changes to manage nutrients. They will have a problem with this stocking rate rule. As the science evolves and understanding for everyone improves through participating in joint programmes that better inform decision-making, farmers will and do adapt. It’s the broad brushstroke rules that limit the capacity of the business and force land acquisition to meet paper-based stocking rates that cause the concern.

The responsibility and onus is on the minister and the Department to sort this out using the best advice and research from Teagasc.

CAP changes hit

productive farmers

This week’s Teagasc review and outlook conference delivered clear and concise projections for each sector.

For dairy and tillage, it looks likely that gains made in 2022 will be wiped away fast in 2023. Teagasc economists predict a 30% drop in dairy family farm income and a 48% drop in a tillage family farm income.

The pig sector looks set for a profitable year in 2023 and the only way is up for forestry as hectares planted fell to 2,340ha in 2022, way off the 8,000ha planned.

However, it was Dr Fiona Thorne’s presentation about the impact of CAP changes on family farm income that stood out for me.

She presented data showing that the big losers in the new CAP, starting January 2023, are those farmers producing most of the sheep and cattle in the country. The cattle and sheep sector are most dependent on CAP money so any downward movement in funding takes money out of their pockets.

Thorne’s work shows cattle and sheep farmers producing 80% of the meat are set to lose in the new CAP. If this analysis was available when the minister was on tour last year, it would have been great to use it to inform the debate.

Releasing it at this stage merely allows us reflect on the outcome of the decisions taken.

Long story short – it effectively is clear evidence that cattle and sheep farmers producing 80% of the Irish output are going to lose out further as they produce this food.

Congratulations to award winners

The long hours, hard work, and the ultimate perseverance to understand a topic or detail pays off when you get nominated and subsequently awarded a prize for creating valuable content by your peers.

Last Friday night at the Guild of Agricultural Journalists annual ceremony, Barry Murphy, Amii McKeever, Siobhán Walsh and photographer Andy Gibson all got rewarded for work published in the Irish Farmers Journal and Irish Country Living.

As a team, across all our publications, we strive to provide independent, unique, well thought out and structured content in print, digital, audio and visual. We congratulate and salute our winners.

\ Jim Cogan

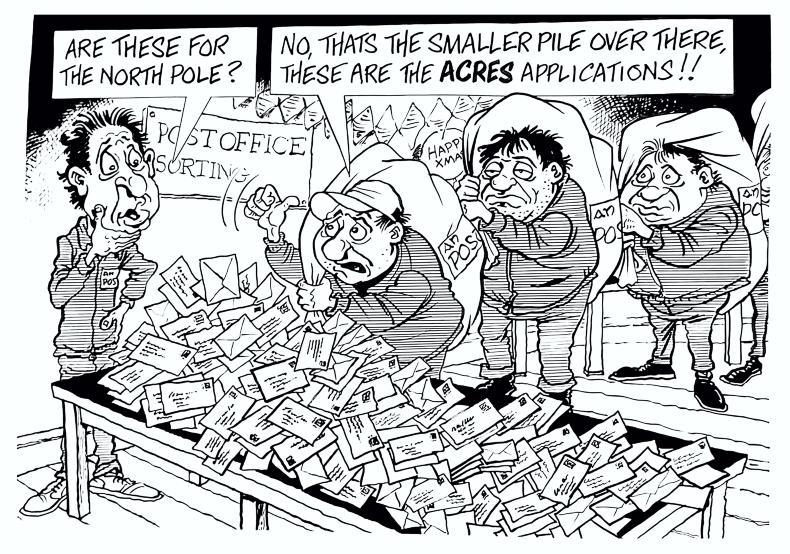

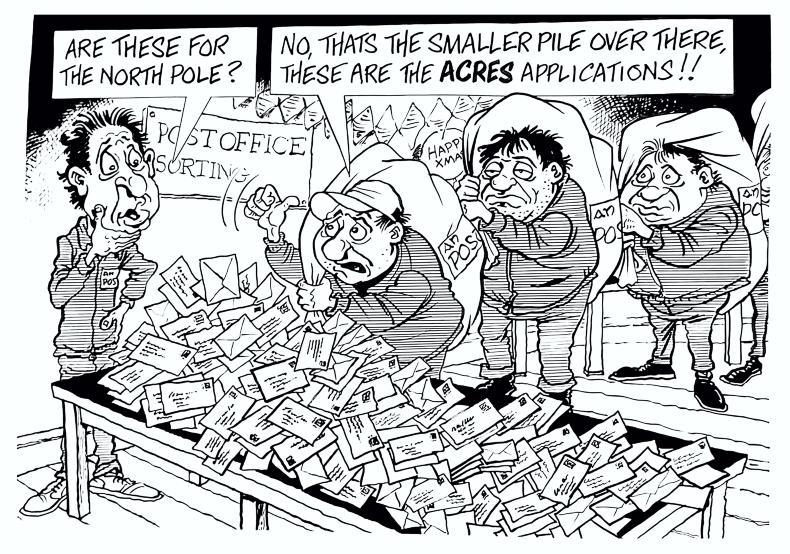

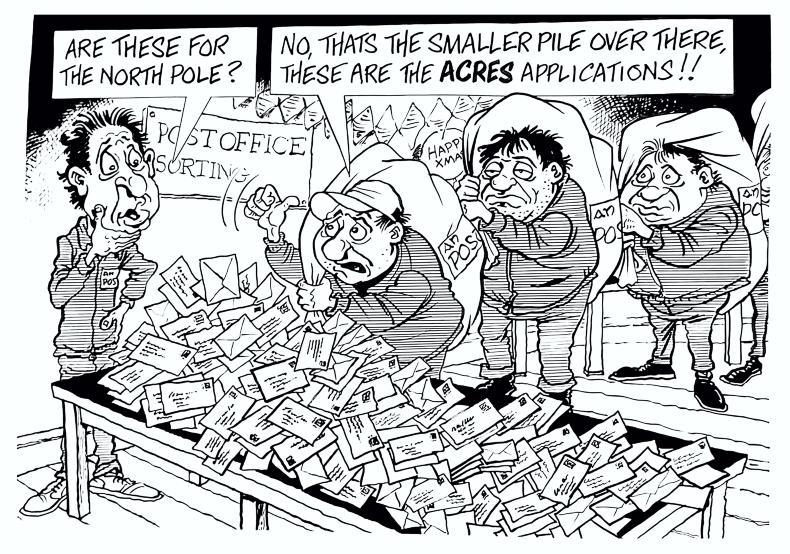

Spaces need to be found for ACRES

Given the mileage the Department of Agriculture and the Government achieved from numerous announcements and launches for its flagship new environmental scheme, ACRES, it would be a huge own goal for the Minister for Agriculture and the Department if they can’t find a home for the 46,000 farmers who have applied. Limiting participation when we are asking farmers to invest in new technology and buy into climate ambitions by limiting stock numbers would be nothing short of a disaster.

If the Government holds the line that there are only 30,000 places and walks away from these farmers it would be a catastrophe.

Farmers need

to take a close look at costs

It’s clear from the Teagasc National beef conference held in Galway on Tuesday and the Outlook conference earlier in the week that despite lower inputs the beef sector is not immune to the rising costs at farm level.

While everyone is waiting for the minister’s acceptance or next steps following the publication of the final Food Vision report, farmers should ask themselves what can they do to reduce costs at farm level.

Has red clover as discussed at the conference a part to play on an outfarm? Could it reduce the bag nitrogen required and hence reduce costs?

If the minister puts an exit or cull package on the table, farmers need to know what each cow is returning in order to assess the opportunity if and when it arises.

Ireland’s nitrates derogation provides farmers an opportunity to farm at higher stocking rates when they take extra steps to protect the environment. In effect, a farmer must not exceed a stocking rate of two dairy cows per hectare without a derogation. However, they can farm at 2.7LU/ha if approved for a derogation. The derogation is available to grassland farmers on an individual basis.

The key change coming in the current nitrate debacle will see the threshold for a derogation lowered to 220kg of organic nitrogen per hectare. This, along with other proposed changes, effectively means the allowed stocking rate on a 40ha farm will reduce from 118 cows to a 96 cows. This has huge implications for the viability of dairy farm businesses.

So why is this change important? It means a farmer who is doing everything right in terms of slurry storage, nutrient use, incorporating clover and managing nutrient runoff is capped at a low level on the number of cows he or she can milk on their holding.

The Irish dairy system has built its success on grass-based farming where feed is grown and harvested on the land where cows are held. Far too often, professionals use the word ‘intensive’ in an Irish context meaning stocked between 2.5 and 3.0 cows/ha. Let’s be clear – in some parts of Europe and elsewhere there are 1,000 cows on 10ha, the equivalent of 100 cows/ha. That’s intensive. Feed and water are brought from all corners of the world to feed animals.

Irish farmers are unique in Europe with our seasonal grass-based system of production matching grass growth patterns. Up to now, the permitted stocking rates have allowed this continue. The irony of lowering the stocking rate is it could push Irish farmers down a higher yield per cow road that threatens to release more carbon and push farmers into more purchased feeds.

The red tape for some landowners who traditionally have taken in nutrients from other farmers will prevent them accepting these nutrients in the future

Why? Land is the limiting factor. If a cow at 6,500l is classified as producing 106kg of organic nitrogen she might as well be producing 10,000l.

A farm family needs a certain volume of milk to dilute fixed and variable costs and provide a viable income and opportunity for succession.

What will be the knock-on impact of the proposed changes? The changes mean exporting nutrients off farm will become much more restricted. The red tape for some landowners who traditionally have taken in nutrients from other farmers will prevent them accepting these nutrients in the future. These non-dairy land owners could turn to more purchased artificial nutrients instead.

Land available to purchase, lease or rent will rise in value. The profitability of dairy will squeeze other enterprises out of existence. Indeed, this is already happening.

So what’s the state of play and what can the Department do? Firstly, the derogation is in place until 2025. However, a review is scheduled for September 2023. The water quality results to be used in that review are effectively gathered already (to the end of 2022). The raft of changes already imposed and changes coming next year in the continuing tightening of derogation rules will not get a chance to deliver any benefit to our waterways.

Secondly, using two years of water data in isolation for the review seems nonsensical from a scientific point of view. There are significant effects that could jeopardise the measurement integrity.

Thirdly, the mechanics of what I term the “Irish factor” on how milk is produced on this island must be further reinforced and understood at European level. This lies squarely with our Department officials. In addition, rural politicians need to understand what is at play and make their voices heard. Farm organisations must stand united on this. It has become crystal clear the consultation process with farm organisations failed to fully reveal the stocking rate reduction that was on the cards.

Farmers will, or at least should have, no problem with many of the proposed positive changes to manage nutrients. They will have a problem with this stocking rate rule. As the science evolves and understanding for everyone improves through participating in joint programmes that better inform decision-making, farmers will and do adapt. It’s the broad brushstroke rules that limit the capacity of the business and force land acquisition to meet paper-based stocking rates that cause the concern.

The responsibility and onus is on the minister and the Department to sort this out using the best advice and research from Teagasc.

CAP changes hit

productive farmers

This week’s Teagasc review and outlook conference delivered clear and concise projections for each sector.

For dairy and tillage, it looks likely that gains made in 2022 will be wiped away fast in 2023. Teagasc economists predict a 30% drop in dairy family farm income and a 48% drop in a tillage family farm income.

The pig sector looks set for a profitable year in 2023 and the only way is up for forestry as hectares planted fell to 2,340ha in 2022, way off the 8,000ha planned.

However, it was Dr Fiona Thorne’s presentation about the impact of CAP changes on family farm income that stood out for me.

She presented data showing that the big losers in the new CAP, starting January 2023, are those farmers producing most of the sheep and cattle in the country. The cattle and sheep sector are most dependent on CAP money so any downward movement in funding takes money out of their pockets.

Thorne’s work shows cattle and sheep farmers producing 80% of the meat are set to lose in the new CAP. If this analysis was available when the minister was on tour last year, it would have been great to use it to inform the debate.

Releasing it at this stage merely allows us reflect on the outcome of the decisions taken.

Long story short – it effectively is clear evidence that cattle and sheep farmers producing 80% of the Irish output are going to lose out further as they produce this food.

Congratulations to award winners

The long hours, hard work, and the ultimate perseverance to understand a topic or detail pays off when you get nominated and subsequently awarded a prize for creating valuable content by your peers.

Last Friday night at the Guild of Agricultural Journalists annual ceremony, Barry Murphy, Amii McKeever, Siobhán Walsh and photographer Andy Gibson all got rewarded for work published in the Irish Farmers Journal and Irish Country Living.

As a team, across all our publications, we strive to provide independent, unique, well thought out and structured content in print, digital, audio and visual. We congratulate and salute our winners.

\ Jim Cogan

Spaces need to be found for ACRES

Given the mileage the Department of Agriculture and the Government achieved from numerous announcements and launches for its flagship new environmental scheme, ACRES, it would be a huge own goal for the Minister for Agriculture and the Department if they can’t find a home for the 46,000 farmers who have applied. Limiting participation when we are asking farmers to invest in new technology and buy into climate ambitions by limiting stock numbers would be nothing short of a disaster.

If the Government holds the line that there are only 30,000 places and walks away from these farmers it would be a catastrophe.

Farmers need

to take a close look at costs

It’s clear from the Teagasc National beef conference held in Galway on Tuesday and the Outlook conference earlier in the week that despite lower inputs the beef sector is not immune to the rising costs at farm level.

While everyone is waiting for the minister’s acceptance or next steps following the publication of the final Food Vision report, farmers should ask themselves what can they do to reduce costs at farm level.

Has red clover as discussed at the conference a part to play on an outfarm? Could it reduce the bag nitrogen required and hence reduce costs?

If the minister puts an exit or cull package on the table, farmers need to know what each cow is returning in order to assess the opportunity if and when it arises.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: