Any news that appears to increase the demand for grain anywhere around the globe is potentially good for crop producers. And when the most populous nation on earth decides to increase its bioethanol mandate in its transport fuel, the demand consequences can be significant. When US policy did the same thing in the mid 2000s it generated an additional domestic demand for 120m to 140m tonnes of maize (corn) to produce bioethanol.

In late 2017, China’s National Energy Administration (NEA) published a report detailing the country’s intent to implement a nationwide E10 ethanol blending mandate. The blueprint, the ‘‘Expansion of Ethanol Production and Promotion for Transportation Fuel’’, outlines the commitment to boost production of fuel ethanol and increase the usage of E10 gasoline (which contains 10% ethanol) nationwide by 2020. The blend rate for E10 ethanol for transport fuel in China currently stands at 2.3%.

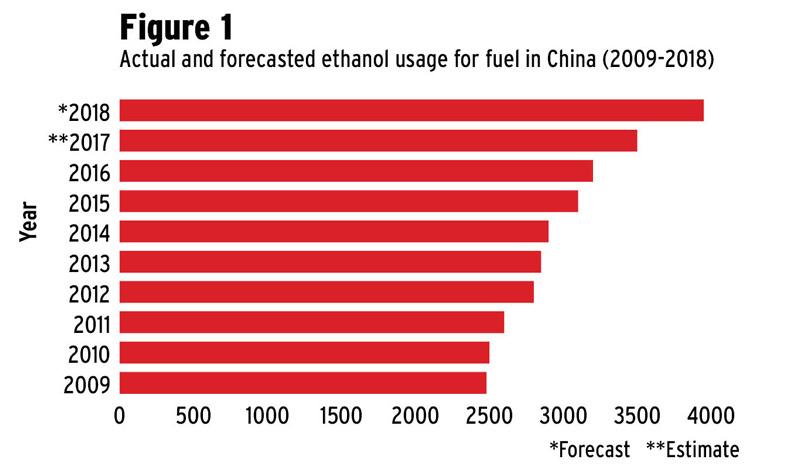

Eleven provinces and 40 local municipal governments in China have adopted local fuel ethanol blending mandates. China’s ethanol-for-fuel demand has been steadily increasing over the years reflecting the government’s efforts to promote blending. The 2018 fuel ethanol consumption is forecast at 3,950m litres (Figure 1). This is up 400m litres from 2017. Ethanol is seen as a critical component for China’s greenhouse gas emissions commitments.

Corn demand

The details of the mandate have not yet been fully disclosed, so it is unclear how China will generate more than a fourfold output growth within three years. Corn is a major feedstock used in ethanol production with 70% of all fuel ethanol produced on the country derived from that crop.

The US National Bureau of Statistics estimated that total gasoline consumption in China in 2016 was 109mt (120m US tonnes). If this estimate is correct, it would mean that attaining the E10 blend target across China will require 15,216m litres of transportation fuel ethanol, which is equivalent to 36mt of corn feedstock.

In order to fulfil this mandate, China will require the aforementioned volume of corn, according to Naomi Blohm, senior market adviser with Steward-Peterson. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that China’s new appetite for ethanol will need to be satisfied through substantial increases in corn imports, as has previously been suggested. The strongest indications of this are the advancements in China’s indigenous corn production and the increasing volumes of ethanol being imported.

China also has substantial stores of corn which are not suitable for feed and may be used for ethanol production. Therefore, any substantial increase in demand for corn will most likely be seen closer to 2020. This means that, while producers may not see any significant increase in the price of corn, prices are unlikely to dip below the levels seen in recent years.

While these developments are unlikely to drastically transform the global grain market overnight, they shed some positive light on a relatively dreary grain market by highlighting the fact that new markets are developing which may someday help to tighten the supply and demand gap.