A national poll conducted in 2012 to find Ireland’s favourite painting resulted in a clear victory for The Meeting on the Turret Stairs by Frederic William Burton.

The curators at the National Gallery of Ireland (NGI) were not surprised at the result. Though Burton lacks the high profile of some of our other noted artists, his works on display at the NGI remain perennial favourites.

Burton was born in Wicklow in 1816 and grew up in Corofin, Co Clare.

Burton’s father, Samuel, was an amateur painter who encouraged his son’s artistic endeavours. In 1826, Frederic enrolled in the Dublin Society Schools, where he received instruction in drawing and watercolour painting.

Something of a prodigy, he was exhibiting at the Royal Hibernian Academy by the age of 16. He was to remain a watercolourist all his life – it is said that he could not bear the smell of the solvents used with oil paints. He worked his paintings up painstakingly, making dozens of sketches, building up his colours in layers and working with the finest of brushes to create an almost hyper-real effect.

His friendship with fellow artist and antiquarian George Petrie was to be an important one for Burton. Petrie set Burton’s artistic career on a new path by bringing him on a survey trip around the West of Ireland, documenting ruined sites, and the young artist developed an abiding love of Connaught and its people.

A nationalist in the gentlemanly tradition of the Young Ireland movement, Burton painted sympathetic, romantic scenes of peasant life – the most significant of which was The Aran Fisherman’s Drowned Child (1841). Burton was still in his early 20s when he captured the scene, but already a master at evoking emotion.

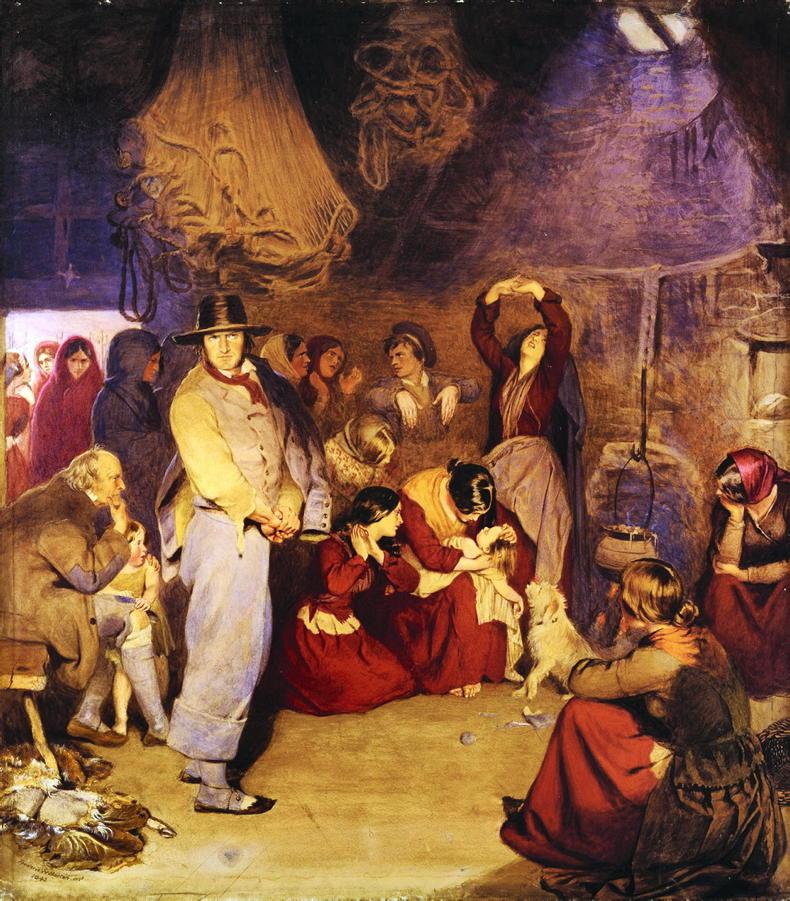

‘The Aran Fisherman’s Drowned Child’ by Frederic William Burton.

The viewer is invited into the interior of a fisherman’s cottage, and immediately confronted with the tragedy of the drowned child laid on its mother’s lap. The child’s father dominates the foreground, a handsome, romantic figure in the high-crowned hat and indigo-dyed trousers typical of the time and place. Behind him grief in all its forms is on display; the stricken mother, the grandfather who has seen too much death before, the distraught neighbours, and even the official mourners in the doorway, who will presently commence keening over the child’s body.

Aside from the palpable sadness of the scene, the painting is rich in historical detail.

Around the feet of the elderly grandfather are spread several undressed hides, from which he would have been making pampooties

The women are shawled, cloaked and wears petticoats which were dyed a striking red using madder. The young child is garbed in the long dress which was worn by both boys and girls to confuse fairies intent on stealing them.

The cooking pot is suspended on a moveable crane above the fire, and a line of fish is strung in the smoke hole.

Elsewhere, the high roof space is hung with masses of drying fishing nets. Around the feet of the elderly grandfather are spread several undressed hides, from which he would have been making pampooties, the traditional rawhide shoes of the Aran Islands.

The undoubted authenticity of the scene notwithstanding, Burton did not actually visit the Aran Islands until years after the painting was complete. The Aran Fisherman was probably sketched up in the Claddagh area of Galway. He made over 50 preparatory drawings, some of which survive today.

My best days have been connected with Ireland

Burton spent seven years in Bavaria during the 1850s before settling permanently in London, where he was appointed director of the NGI in 1874.

In the 20 years that he held this post he was responsible for many important acquisitions. Nonetheless, in his later years he remarked to his friend Lady Augusta Gregory: “My best days have been connected with Ireland.”

Read more

Great Irish Paintings: ‘The Biggest Walls in the Counthry was in it’ by Snaffles

Great Irish paintings: Lady Elizabeth Southerden Butler

A national poll conducted in 2012 to find Ireland’s favourite painting resulted in a clear victory for The Meeting on the Turret Stairs by Frederic William Burton.

The curators at the National Gallery of Ireland (NGI) were not surprised at the result. Though Burton lacks the high profile of some of our other noted artists, his works on display at the NGI remain perennial favourites.

Burton was born in Wicklow in 1816 and grew up in Corofin, Co Clare.

Burton’s father, Samuel, was an amateur painter who encouraged his son’s artistic endeavours. In 1826, Frederic enrolled in the Dublin Society Schools, where he received instruction in drawing and watercolour painting.

Something of a prodigy, he was exhibiting at the Royal Hibernian Academy by the age of 16. He was to remain a watercolourist all his life – it is said that he could not bear the smell of the solvents used with oil paints. He worked his paintings up painstakingly, making dozens of sketches, building up his colours in layers and working with the finest of brushes to create an almost hyper-real effect.

His friendship with fellow artist and antiquarian George Petrie was to be an important one for Burton. Petrie set Burton’s artistic career on a new path by bringing him on a survey trip around the West of Ireland, documenting ruined sites, and the young artist developed an abiding love of Connaught and its people.

A nationalist in the gentlemanly tradition of the Young Ireland movement, Burton painted sympathetic, romantic scenes of peasant life – the most significant of which was The Aran Fisherman’s Drowned Child (1841). Burton was still in his early 20s when he captured the scene, but already a master at evoking emotion.

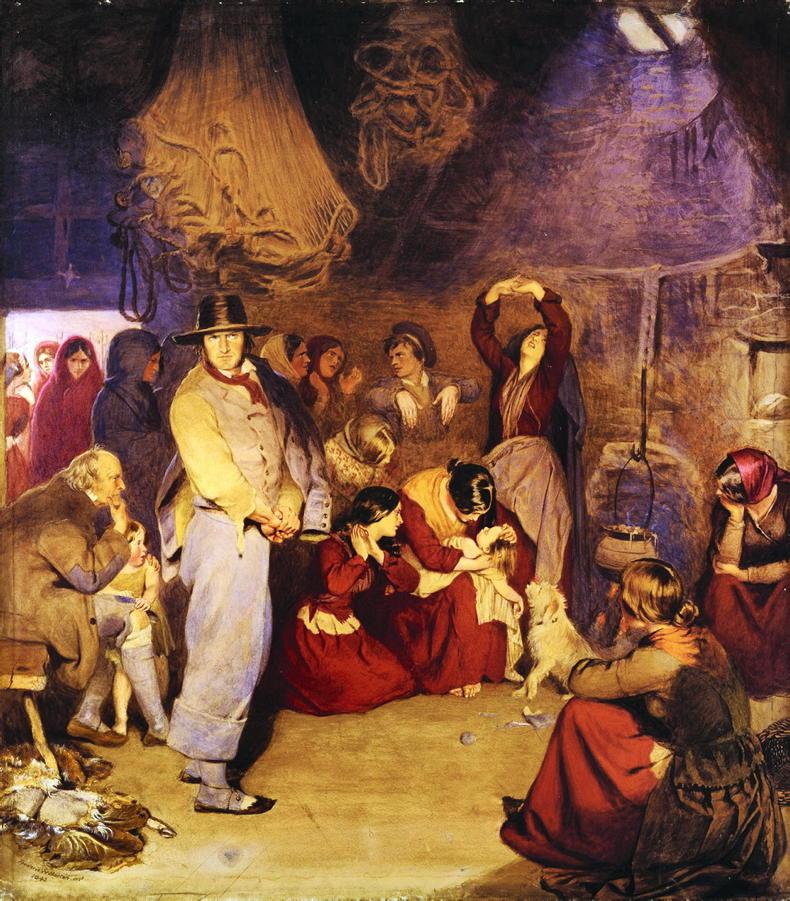

‘The Aran Fisherman’s Drowned Child’ by Frederic William Burton.

The viewer is invited into the interior of a fisherman’s cottage, and immediately confronted with the tragedy of the drowned child laid on its mother’s lap. The child’s father dominates the foreground, a handsome, romantic figure in the high-crowned hat and indigo-dyed trousers typical of the time and place. Behind him grief in all its forms is on display; the stricken mother, the grandfather who has seen too much death before, the distraught neighbours, and even the official mourners in the doorway, who will presently commence keening over the child’s body.

Aside from the palpable sadness of the scene, the painting is rich in historical detail.

Around the feet of the elderly grandfather are spread several undressed hides, from which he would have been making pampooties

The women are shawled, cloaked and wears petticoats which were dyed a striking red using madder. The young child is garbed in the long dress which was worn by both boys and girls to confuse fairies intent on stealing them.

The cooking pot is suspended on a moveable crane above the fire, and a line of fish is strung in the smoke hole.

Elsewhere, the high roof space is hung with masses of drying fishing nets. Around the feet of the elderly grandfather are spread several undressed hides, from which he would have been making pampooties, the traditional rawhide shoes of the Aran Islands.

The undoubted authenticity of the scene notwithstanding, Burton did not actually visit the Aran Islands until years after the painting was complete. The Aran Fisherman was probably sketched up in the Claddagh area of Galway. He made over 50 preparatory drawings, some of which survive today.

My best days have been connected with Ireland

Burton spent seven years in Bavaria during the 1850s before settling permanently in London, where he was appointed director of the NGI in 1874.

In the 20 years that he held this post he was responsible for many important acquisitions. Nonetheless, in his later years he remarked to his friend Lady Augusta Gregory: “My best days have been connected with Ireland.”

Read more

Great Irish Paintings: ‘The Biggest Walls in the Counthry was in it’ by Snaffles

Great Irish paintings: Lady Elizabeth Southerden Butler

SHARING OPTIONS