On a recent trip to Sweden, the Irish Farmers Journal had the opportunity to visit Svejo Dairy, an organic dairy farm in the rolling Swedish countryside.

Located just outside the town of Mjolby, three hours’ drive from the capital city of Stockholm, Svejo Dairy is easily identified from the main road with its collection of big red and white barns standing out against the vast landscape.

The farm is a family run operation, managed by Mats Carlsson in conjunction with his parents Asa and Ove, sister Emelie and her husband Carl. There are four further non-family staff.

The Carlssons are milking 280 cows and rearing all youngstock across a 570ha platform. The 570ha is split into 300ha of grassland for grazing and silage production, 180ha of rough ground that acts as extensive grazing and a further 90ha of crops.

Peas, oats, wheat and maize are all grown on the farm to make the business as self-sufficient as possible, with organic meal costing over €1,200/tonne.

The farm is leased on a five-year basis which is unusual even in Sweden. The lease is reviewed at the end of the fourth year by the landowner. It is decided then whether the family will be granted another five years or if they will be expected to leave by the end of the fifth year.

The Carlsson’s are heading into their 15th year on the farm next year, with five more years guaranteed. Mats noted this arrangement was not the norm in the region.

Farm leases

“Most farms that are leased, are owned by the local church in the diocese or by the Swedish monarch. Those farms would typically be leased on longer terms, up to 30 years in some cases. Competition is high for those blocks,” he says.

Any development work the Carlssons do on the farm, is done with the security that when they eventually have to leave, the landowner must purchase the development work off them.

This gives some level of security, to allow the business to make investments that will improve the business.

Organics

The Carlssons had previously farmed on a different lease block in the years prior to taking on the farm in Mjolby. On the previous farm, they were operating in a fully conventional system.

The decision to switch to organic farming was initially purely for financial gain.

Their motives have changed however over the years.

The Carlssons now have a real passion for the organic industry and believe it’s the best way to farm from both an animal welfare and environmental point of view.

The farm supplies its milk to Arla Co-op and receives an organic bonus payment which is 19c/l higher than the conventional price.

The price received at the time of the Irish Farmers Journal’s visit was 70c/l with conventional price at 51c/l.

Cows lying on the green bedding produced on farm.

Arla is the main co-operative in the country, processing almost 80% of the Swedish milk pool. The organic proportion of this milk pool has increased to just over 15% of supply in recent years, as the Swedish public is showing a greater demand for organic milk.

In Sweden, government regulations require farmers to allow all cattle access to pasture for a minimum of three months of the year between April and September.

In organic systems, this regulation requires animals to have five months of mandatory access to pasture.

On the Svejo farm, the cows are allowed out from the end of April through to the end of September. The cows are not strictly grazing only grass as they have free access to come and go from the shed with some cows choosing not to leave the shed at all.

“On warm, sunny days, the majority of cows would be out in the field. They don’t do a lot of grazing but they are happier to lie out there. If there’s any rain, they will start running back inside so we like to give them both options.”

At the time of the visit, there was a remarkably even split between cows inside and out. Certain cows obviously had a preference for cubicles versus the outdoors and vice versa.

Milk production

The Svejo herd is predominantly made up of Holstein Friesian cows with roughly 10% of the herd being of the Swedish Red breed. On average, the cows are producing 11,800l/cow.

According to Mats, this high production is down to two main factors, good genetics and high feeding levels.

Genetics has always been a big focus for the Carlssons, who have previously bred the winner of the Elmia Dairy Show.

This is the main annual national dairy show in Sweden and the win is something both Mats and Emelie are clearly very proud of.

Calves are housed in huts for the first month and a half of life.

Their goal over the last number of years has been to try and breed a hardy animal with greater survivability. Ultimately, they want a more well-rounded animal who can still produce more than 11,000l/milk annually.

With such high producing cows, it’s difficult to maintain a decent level of fertility and this shows through in the annual replacement rate at 33%. The average cow in the herd survives just over 2.5 lactations.

While this is low it’s not unique in the Swedish system but it’s something the Carlssons are looking to improve upon.

The cows are calving all-year-round with approximately 25 calving each month.

All cows are dried off two months before they calve and kept in the dry cow barn which is bedded with straw.

Once the cows calve, they rejoin the main herd. As the farm is operating with robots, these cows can get adjusted levels of concentrate feeding.

Mats was clearly very focussed on his detail around breeding cows. Like a lot of indoor high output systems, conception rates can be low and anything that might improve this is very desirable.

The Carlssons are using health and heat detection ear tags to identify the ideal time for insemination, which they find has been a big benefit.

“All cows will get at least two rounds of sexed AI straws first. The milking cows all have an ear tag that works in co-ordination with our DeLaval robots.

The ear tags pick up everything that a collar would. We inseminate cows around 15 hours after the onset of standing heat.

“If they do not keep to either of the first two straws, they will then be served with conventional beef straws,” Mats said.

Mats and his sister Emelie who manage the Svejo farm.

The calving interval of the herd is 386 days which is a strong figure for an all-year round calving herd.

The other area that Mats places a lot of importance on is in the cows’ diets.

The high output cows need huge quantities of feed in order to produce the quantities of milk per cow being achieved on the farm.

The diet is a TMR and the breakdown of the diet being offered at the time of the visit was 1kg of straw, 5kg of wheat, 2kg of oats, 5kg concentrates, 4kg of maize and 8kg of grass silage.

This diet is offered regardless of the potential grass intake. In total, the Svejo grazing block is just 20ha split into 14 paddocks.

The cows get access to a new paddock each day meaning a 14-day round on the farm.

The newly constructed calf shed on the farm.

The paddocks are all located as close as possible to the shed to ensure cows return to the feed passage or ‘feed table’ as they call it.

With the level of production the cows are doing, the Carlssons feel a grass diet wouldn’t allow for the level of intake the cows require to perform in the high output system.

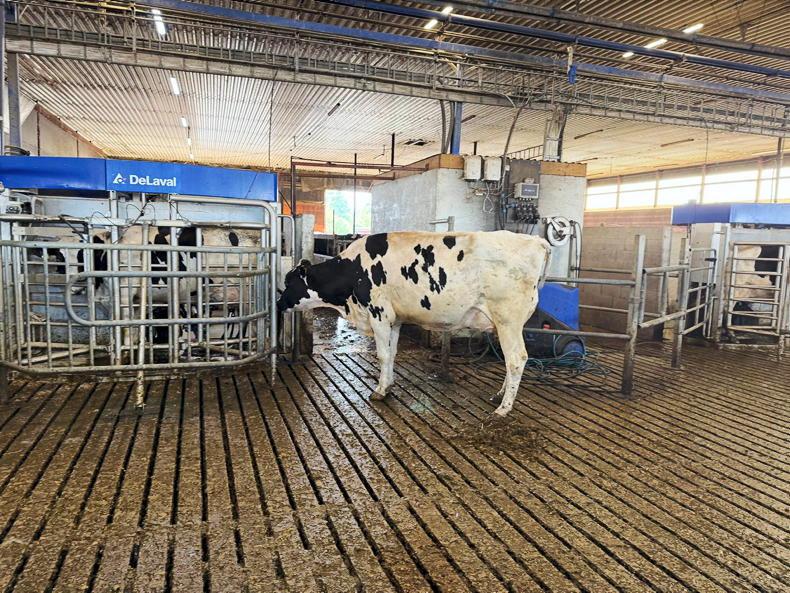

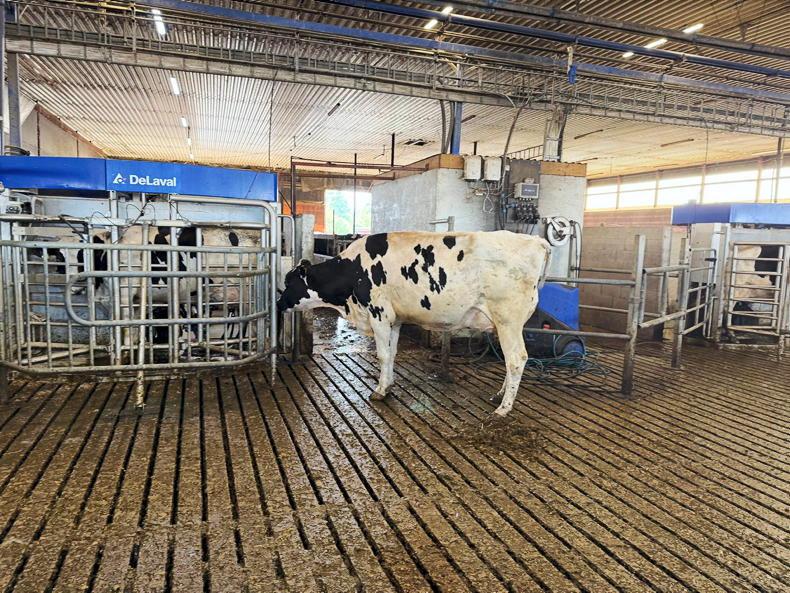

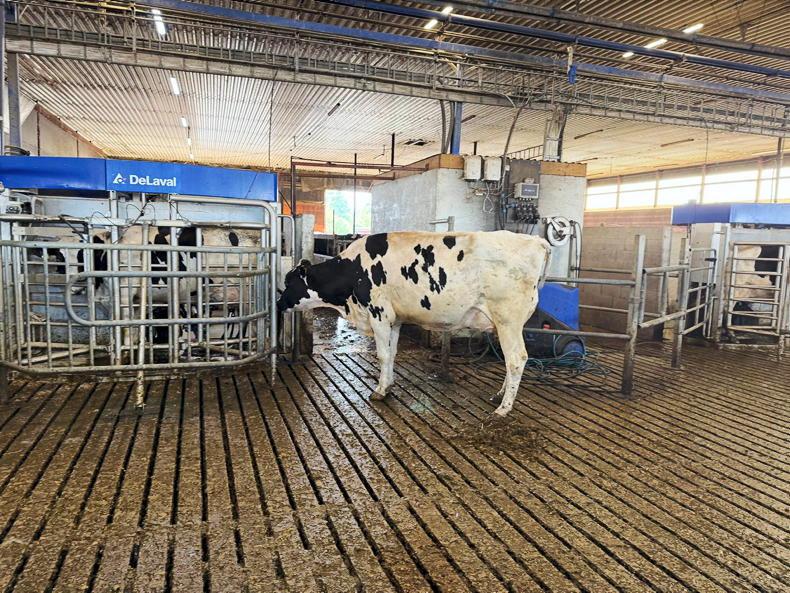

DeLaval robots

Automated milking systems or robots are very common in Sweden as the majority of cows are housed full time and staff are difficult to come by.

The Carlssons are currently milking through four DeLaval robots. Over the summer months while the cows have access to grass, the milking frequency is 2.8 milkings/cow. During the period where cows are fully housed, the milking frequency rises to 3.3 milkings/cow.

The milking time is just over seven minutes per cow with an average daily yield of around 39l/cow. The average constituents of this milk are 3.9% fat and 3.3% protein.

At any one point in the year, there are approximately 50 cows dry, meaning on average there are 55 cows actively milking per robot station.

Cows are required to have five moths outdoor access under Swedish organic regulation.

With higher yielding cows and higher milking frequencies, the Carlssons feel this is a good number for their system. The robot feeds cows on a feed to yield basis but this is tightly controlled by Mats. The Carlssons grow their own wheat, oats and beans so they prefer to feed this as supplement as opposed to the more expensive organic meal.

Technology is fairly advanced on the farm which seems to be a theme throughout Sweden. As well as the robots, the Carlssons are operating a DeLaval OptiDuo robotic feed pusher, which pushes back silage three times a day and an automatic DeLaval robot scraper cleans the shed every two hours.

Youngstock

When calves are born on the farm, they must be left to spend one full day with their mothers under the Swedish organic regulations. From there they’re moved to the calf shed.

Another regulation tied to the organic system is that all calves must be grouped in a minimum of twos.

On the Carlsson’s farm the two calves are housed together in calf huts for a month and a half.

After this time the calves are moved to bigger pens and kept in groups of 10. Calves are fed 8.4l of fresh milk for the first two months. This is fed as 2.8l feed, three times a day.

From two months on, the calves are fed 5l/day in an effort to encourage them to eat more concentrates. The organic meal is costing €1.25/kg so the Carlssons are keen to grow the calves as much as possible in the first two months off milk alone.

Once the calves have been weaned the replacement heifers are then reared as one group on grass with access to a feed mix in the heifer shed.

The feed mix is the same as the milking cows mix with the only exception being the concentrates fed through the robot.

All beef calves are moved to an outblock where they are reared on a grass only diet for the majority of their life.

The bulls are castrated before they are six months old. These beef animals are finished on a diet of peas, wheat and oats which are all grown on the farm.

The average carcass weight of the animals at 21-months-old slaughter comes in at 310kg.

The current organic beef prices in Sweden are equivalent to €6.40/kg however, there is also a further subsidy paid to farmers who rear organic beef which was not disclosed on the day.

Mats and Emilie are responsible for management of the milking herd, replacement heifers and young calves.

The cows are fed a TMR diet, with the majority of the diet produced on farm.

Once the calves are weaned and moved to the outblocks, the responsibility for rearing move to Mat’s parents, Asa and Ove. Emelie’s husband Carl is responsible for all crops grown on the farm.

The additional four staff are split between all aspects of the business. They each work a five-day week with a 6am start and 6pm finish.

With cows indoor for the majority of the year, slurry storage is a significant investment for Swedish farms. On the Svejo farm there is capacity for 12 months storage in total.

They have two concrete lined lagoons and a small biogas plant that was recently constructed on the farm.

The biogas plant was an investment by the farm owner, made with the view of producing enough electricity to run the farm business while also selling electricity to the national grid.

The biogas plant is fuelled with any waste feed, bedding and imported chicken manure. There are several farmers in the local areas also supplying the plant with waste and slurry.

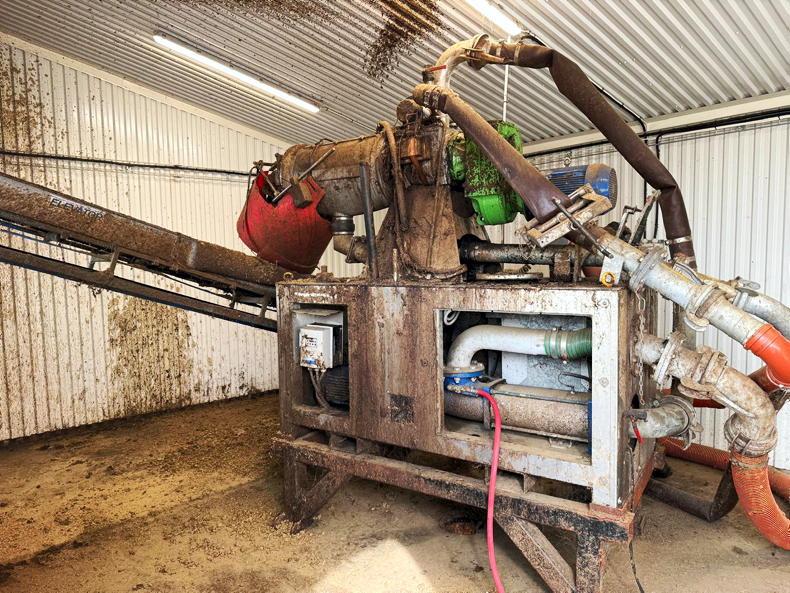

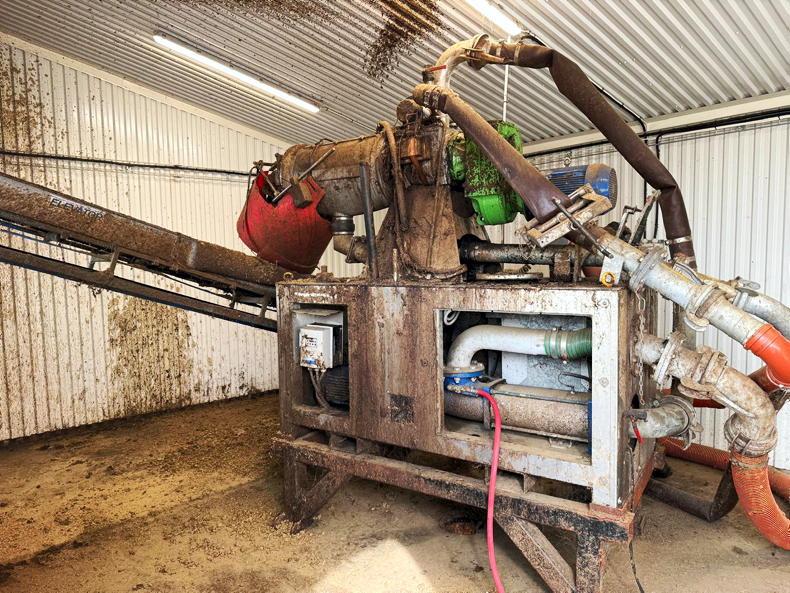

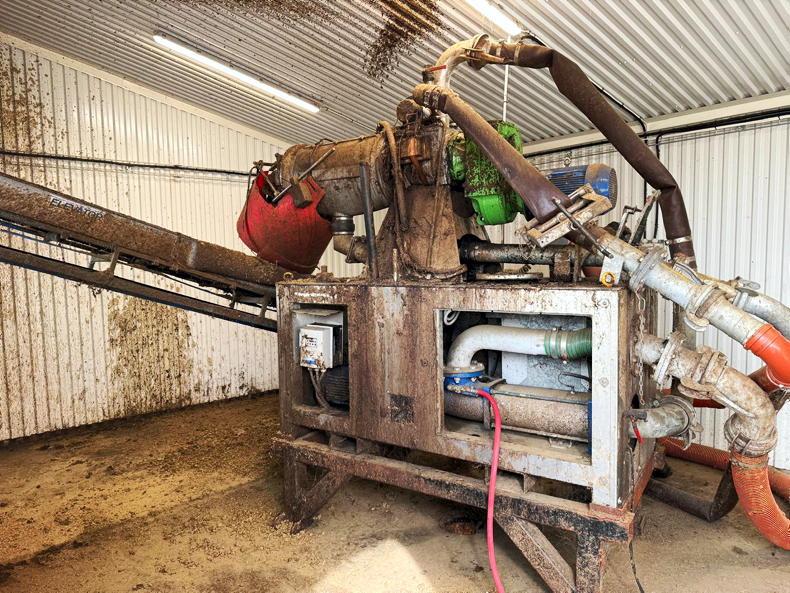

Another investment made by the Carlssons in recent years was a slurry separator capable of separating the liquid component of slurry from the dry matter. The dry matter is then rolled and pressed to form green bedding.

Green bedding is the use of the dry matter fraction of waste product to bed cows and is a common practice in Scandinavian countries according to Mats.

“The separating machine is run for three hours at a time and this will produce enough green bedding for the 280 cows and all of the heifers for one day.

“The liquid fraction of the end product is then spread on our grazing platform. We have no issues with somatic cell count from the green bedding and the cows are exceptionally happy on it,” Mats said.

The cubicles are cleaned twice a day with the manure scraped off and replaced. The green bedding is constantly being recycled on the farm which saves significant costs on lime or sawdust.

The separator cost the equivalent of €45,000 three years ago but the Carlssons are adamant it has paid for itself already.

Future

The future is somewhat uncertain for the family at the moment. They are guaranteed another five years of farming in Mjolby but there’s no certainties from there on out.

Mats gut-feeling is that the landowner is unlikely to extend the lease beyond this.

Land price is similar to Ireland in this region of Sweden, with a cost of €30,000-€50,000/ha. The option of purchasing a farm with scale for 280 cows is not something on Mats radar at the moment either.

While he loves farming and enjoys the day-to-day management, he’s not sure if it’s something he wants to do forever. The current system is quite complex with a fragmented land base. It’s by no means a simple farm to manage with a huge labour requirement for 280 cows.

Mats is not entirely sure what the future holds for the family but for now, they’ll continue to make the most of what they have and strive to make their system as profitable as possible.

The slurry separating machine to produce green bedding.

There are four DeLaval robots on the farm, with 55 cows milking per station at any point of the year.

On a recent trip to Sweden, the Irish Farmers Journal had the opportunity to visit Svejo Dairy, an organic dairy farm in the rolling Swedish countryside.

Located just outside the town of Mjolby, three hours’ drive from the capital city of Stockholm, Svejo Dairy is easily identified from the main road with its collection of big red and white barns standing out against the vast landscape.

The farm is a family run operation, managed by Mats Carlsson in conjunction with his parents Asa and Ove, sister Emelie and her husband Carl. There are four further non-family staff.

The Carlssons are milking 280 cows and rearing all youngstock across a 570ha platform. The 570ha is split into 300ha of grassland for grazing and silage production, 180ha of rough ground that acts as extensive grazing and a further 90ha of crops.

Peas, oats, wheat and maize are all grown on the farm to make the business as self-sufficient as possible, with organic meal costing over €1,200/tonne.

The farm is leased on a five-year basis which is unusual even in Sweden. The lease is reviewed at the end of the fourth year by the landowner. It is decided then whether the family will be granted another five years or if they will be expected to leave by the end of the fifth year.

The Carlsson’s are heading into their 15th year on the farm next year, with five more years guaranteed. Mats noted this arrangement was not the norm in the region.

Farm leases

“Most farms that are leased, are owned by the local church in the diocese or by the Swedish monarch. Those farms would typically be leased on longer terms, up to 30 years in some cases. Competition is high for those blocks,” he says.

Any development work the Carlssons do on the farm, is done with the security that when they eventually have to leave, the landowner must purchase the development work off them.

This gives some level of security, to allow the business to make investments that will improve the business.

Organics

The Carlssons had previously farmed on a different lease block in the years prior to taking on the farm in Mjolby. On the previous farm, they were operating in a fully conventional system.

The decision to switch to organic farming was initially purely for financial gain.

Their motives have changed however over the years.

The Carlssons now have a real passion for the organic industry and believe it’s the best way to farm from both an animal welfare and environmental point of view.

The farm supplies its milk to Arla Co-op and receives an organic bonus payment which is 19c/l higher than the conventional price.

The price received at the time of the Irish Farmers Journal’s visit was 70c/l with conventional price at 51c/l.

Cows lying on the green bedding produced on farm.

Arla is the main co-operative in the country, processing almost 80% of the Swedish milk pool. The organic proportion of this milk pool has increased to just over 15% of supply in recent years, as the Swedish public is showing a greater demand for organic milk.

In Sweden, government regulations require farmers to allow all cattle access to pasture for a minimum of three months of the year between April and September.

In organic systems, this regulation requires animals to have five months of mandatory access to pasture.

On the Svejo farm, the cows are allowed out from the end of April through to the end of September. The cows are not strictly grazing only grass as they have free access to come and go from the shed with some cows choosing not to leave the shed at all.

“On warm, sunny days, the majority of cows would be out in the field. They don’t do a lot of grazing but they are happier to lie out there. If there’s any rain, they will start running back inside so we like to give them both options.”

At the time of the visit, there was a remarkably even split between cows inside and out. Certain cows obviously had a preference for cubicles versus the outdoors and vice versa.

Milk production

The Svejo herd is predominantly made up of Holstein Friesian cows with roughly 10% of the herd being of the Swedish Red breed. On average, the cows are producing 11,800l/cow.

According to Mats, this high production is down to two main factors, good genetics and high feeding levels.

Genetics has always been a big focus for the Carlssons, who have previously bred the winner of the Elmia Dairy Show.

This is the main annual national dairy show in Sweden and the win is something both Mats and Emelie are clearly very proud of.

Calves are housed in huts for the first month and a half of life.

Their goal over the last number of years has been to try and breed a hardy animal with greater survivability. Ultimately, they want a more well-rounded animal who can still produce more than 11,000l/milk annually.

With such high producing cows, it’s difficult to maintain a decent level of fertility and this shows through in the annual replacement rate at 33%. The average cow in the herd survives just over 2.5 lactations.

While this is low it’s not unique in the Swedish system but it’s something the Carlssons are looking to improve upon.

The cows are calving all-year-round with approximately 25 calving each month.

All cows are dried off two months before they calve and kept in the dry cow barn which is bedded with straw.

Once the cows calve, they rejoin the main herd. As the farm is operating with robots, these cows can get adjusted levels of concentrate feeding.

Mats was clearly very focussed on his detail around breeding cows. Like a lot of indoor high output systems, conception rates can be low and anything that might improve this is very desirable.

The Carlssons are using health and heat detection ear tags to identify the ideal time for insemination, which they find has been a big benefit.

“All cows will get at least two rounds of sexed AI straws first. The milking cows all have an ear tag that works in co-ordination with our DeLaval robots.

The ear tags pick up everything that a collar would. We inseminate cows around 15 hours after the onset of standing heat.

“If they do not keep to either of the first two straws, they will then be served with conventional beef straws,” Mats said.

Mats and his sister Emelie who manage the Svejo farm.

The calving interval of the herd is 386 days which is a strong figure for an all-year round calving herd.

The other area that Mats places a lot of importance on is in the cows’ diets.

The high output cows need huge quantities of feed in order to produce the quantities of milk per cow being achieved on the farm.

The diet is a TMR and the breakdown of the diet being offered at the time of the visit was 1kg of straw, 5kg of wheat, 2kg of oats, 5kg concentrates, 4kg of maize and 8kg of grass silage.

This diet is offered regardless of the potential grass intake. In total, the Svejo grazing block is just 20ha split into 14 paddocks.

The cows get access to a new paddock each day meaning a 14-day round on the farm.

The newly constructed calf shed on the farm.

The paddocks are all located as close as possible to the shed to ensure cows return to the feed passage or ‘feed table’ as they call it.

With the level of production the cows are doing, the Carlssons feel a grass diet wouldn’t allow for the level of intake the cows require to perform in the high output system.

DeLaval robots

Automated milking systems or robots are very common in Sweden as the majority of cows are housed full time and staff are difficult to come by.

The Carlssons are currently milking through four DeLaval robots. Over the summer months while the cows have access to grass, the milking frequency is 2.8 milkings/cow. During the period where cows are fully housed, the milking frequency rises to 3.3 milkings/cow.

The milking time is just over seven minutes per cow with an average daily yield of around 39l/cow. The average constituents of this milk are 3.9% fat and 3.3% protein.

At any one point in the year, there are approximately 50 cows dry, meaning on average there are 55 cows actively milking per robot station.

Cows are required to have five moths outdoor access under Swedish organic regulation.

With higher yielding cows and higher milking frequencies, the Carlssons feel this is a good number for their system. The robot feeds cows on a feed to yield basis but this is tightly controlled by Mats. The Carlssons grow their own wheat, oats and beans so they prefer to feed this as supplement as opposed to the more expensive organic meal.

Technology is fairly advanced on the farm which seems to be a theme throughout Sweden. As well as the robots, the Carlssons are operating a DeLaval OptiDuo robotic feed pusher, which pushes back silage three times a day and an automatic DeLaval robot scraper cleans the shed every two hours.

Youngstock

When calves are born on the farm, they must be left to spend one full day with their mothers under the Swedish organic regulations. From there they’re moved to the calf shed.

Another regulation tied to the organic system is that all calves must be grouped in a minimum of twos.

On the Carlsson’s farm the two calves are housed together in calf huts for a month and a half.

After this time the calves are moved to bigger pens and kept in groups of 10. Calves are fed 8.4l of fresh milk for the first two months. This is fed as 2.8l feed, three times a day.

From two months on, the calves are fed 5l/day in an effort to encourage them to eat more concentrates. The organic meal is costing €1.25/kg so the Carlssons are keen to grow the calves as much as possible in the first two months off milk alone.

Once the calves have been weaned the replacement heifers are then reared as one group on grass with access to a feed mix in the heifer shed.

The feed mix is the same as the milking cows mix with the only exception being the concentrates fed through the robot.

All beef calves are moved to an outblock where they are reared on a grass only diet for the majority of their life.

The bulls are castrated before they are six months old. These beef animals are finished on a diet of peas, wheat and oats which are all grown on the farm.

The average carcass weight of the animals at 21-months-old slaughter comes in at 310kg.

The current organic beef prices in Sweden are equivalent to €6.40/kg however, there is also a further subsidy paid to farmers who rear organic beef which was not disclosed on the day.

Mats and Emilie are responsible for management of the milking herd, replacement heifers and young calves.

The cows are fed a TMR diet, with the majority of the diet produced on farm.

Once the calves are weaned and moved to the outblocks, the responsibility for rearing move to Mat’s parents, Asa and Ove. Emelie’s husband Carl is responsible for all crops grown on the farm.

The additional four staff are split between all aspects of the business. They each work a five-day week with a 6am start and 6pm finish.

With cows indoor for the majority of the year, slurry storage is a significant investment for Swedish farms. On the Svejo farm there is capacity for 12 months storage in total.

They have two concrete lined lagoons and a small biogas plant that was recently constructed on the farm.

The biogas plant was an investment by the farm owner, made with the view of producing enough electricity to run the farm business while also selling electricity to the national grid.

The biogas plant is fuelled with any waste feed, bedding and imported chicken manure. There are several farmers in the local areas also supplying the plant with waste and slurry.

Another investment made by the Carlssons in recent years was a slurry separator capable of separating the liquid component of slurry from the dry matter. The dry matter is then rolled and pressed to form green bedding.

Green bedding is the use of the dry matter fraction of waste product to bed cows and is a common practice in Scandinavian countries according to Mats.

“The separating machine is run for three hours at a time and this will produce enough green bedding for the 280 cows and all of the heifers for one day.

“The liquid fraction of the end product is then spread on our grazing platform. We have no issues with somatic cell count from the green bedding and the cows are exceptionally happy on it,” Mats said.

The cubicles are cleaned twice a day with the manure scraped off and replaced. The green bedding is constantly being recycled on the farm which saves significant costs on lime or sawdust.

The separator cost the equivalent of €45,000 three years ago but the Carlssons are adamant it has paid for itself already.

Future

The future is somewhat uncertain for the family at the moment. They are guaranteed another five years of farming in Mjolby but there’s no certainties from there on out.

Mats gut-feeling is that the landowner is unlikely to extend the lease beyond this.

Land price is similar to Ireland in this region of Sweden, with a cost of €30,000-€50,000/ha. The option of purchasing a farm with scale for 280 cows is not something on Mats radar at the moment either.

While he loves farming and enjoys the day-to-day management, he’s not sure if it’s something he wants to do forever. The current system is quite complex with a fragmented land base. It’s by no means a simple farm to manage with a huge labour requirement for 280 cows.

Mats is not entirely sure what the future holds for the family but for now, they’ll continue to make the most of what they have and strive to make their system as profitable as possible.

The slurry separating machine to produce green bedding.

There are four DeLaval robots on the farm, with 55 cows milking per station at any point of the year.

SHARING OPTIONS