In Ireland, wild oats and bromes are the two most frequently occurring grassweed species in cereal crops.

Due to the traditional level of spring cereal cropping, fields generally have spring wild oats, but occasionally fields can have a mixed population of spring and winter wild oats.

Wild oat seeds have longer dormancy (more than five years) and higher survival rates on burying than most other grassweeds (eg bromes, blackgrass and Italian ryegrass).Plants can emerge from deeper soil depths (more than 10cm).Plants often escape herbicide applications, due to irregular germination.Among the five types of bromes, sterile brome is the most common and is found mainly at the base of ditches, headlands, field margins as well as within crop fields. Other types like great, soft, meadow and rye bromes are also found locally in many fields.

Sterile and great bromes have similar biology with peak-autumn germination; other types have more protracted emergence.Seeds have a short dormancy (less than two years).Seed numbers decline rapidly (80% to 90% per year) when buried, and seeds do not emerge from more than 10cm deep.Both wild oats and bromes are predominantly self-pollinating and so herbicide resistance is relatively slow to develop compared to outcrossing blackgrass or Italian ryegrass. In recent years, we have identified a number of fields where there is difficulty controlling wild oats and bromes effectively with herbicides.

In this article, I discuss the chemical options available and the type of resistance that is evolving to spring post-emergence ACCase/ALS grassweed herbicides. I also outline integrated weed management (IWM) options for wild oat and brome control. This knowledge is critical to improve our ability to control suspect populations, and to prevent resistance development.

Chemical options

There are a number of ways that we can tackle these grassweeds, both within and outside of the crop to be grown:

Glyphosate before sowing the crop to kill previously emerged plants.Residual herbicides, like pendimethalin (Stomp Aqua), flufenacet (Firebird) or prosulfocarb (Defy) in winter cereals applied pre-emergence (24 to 48 hours after drilling) or early post-emergence (autumn treatment) of the crop and weed, and triallate (Avadex Factor) in winter cereals and spring barley, applied pre-emergence (24 to 48 hours after drilling), offers limited control of bromes and/or wild oats.Remember, tank-mixed residual herbicides (eg Firebird + Defy) or stacked products (eg Firebird Met containing DFF + flufenacet + metribuzin) will be most effective and faster-acting than single actives in controlling critical grassweeds. Also, pre-emergence herbicides applied in autumn are unlikely to provide spring wild oats control.

Use non-ACCase and non-ALS herbicide, eg Kerb (propyzamide) in winter oilseed rape for brome control.Spring post-emergence herbicide (contact-only) options include:Axial (ACCase) for wild oat control in barley or wheat (spring and winter);ACCase products like Falcon, Stratos Ultra or Centurion Max in winter oilseed rape for wild oats and bromes; andALS-Pacifica Plus, Monolith or Broadway Star in winter wheat for wild oats and bromes control.Herbicide resistance and types

Our nationwide grassweed survey has shown that fields with high infestations of wild oats or bromes are more likely to develop herbicide resistance or be less sensitive to herbicides.

From the 100 field populations of wild oats screened to-date, herbicide resistance has been found in 15% of populations, with plant survival from full-rate herbicide applications varying from 25% to 100%. These samples were collected in Wexford, Kilkenny, Cork, Tipperary and Kildare.

Those identified as resistant fell into three different categories (Table 1):

Cross-resistance to all three ACCase actives.Cross-resistance to Axial and Falcon.Falcon-resistance only.These results suggest that herbicides from the same group can behave differently in the same field.

The main mechanism of ACCase resistance is target-site resistance (TSR), with non-target-site resistance (NTSR) being partial or at an early stage.

However, ALS herbicides were highly active on all populations tested, including ACCase-resistant populations, when used at the correct plant growth stage (three- to four-leaf).

With over 100 field populations of bromes tested, only a few populations survived the full-field rate of ALS-Pacifica Plus, with plant survival ranging from 10% to 24%.

There is, however, widespread tolerance among brome types (including sterile, great and soft), collected in the Louth/Wexford/Cork triangle, to half-rates of ACCase-Stratos Ultra and/or ALS-Pacifica Plus, with plant survival from 10% to 50%+, which may be due to repetitive use of reduced field rates.

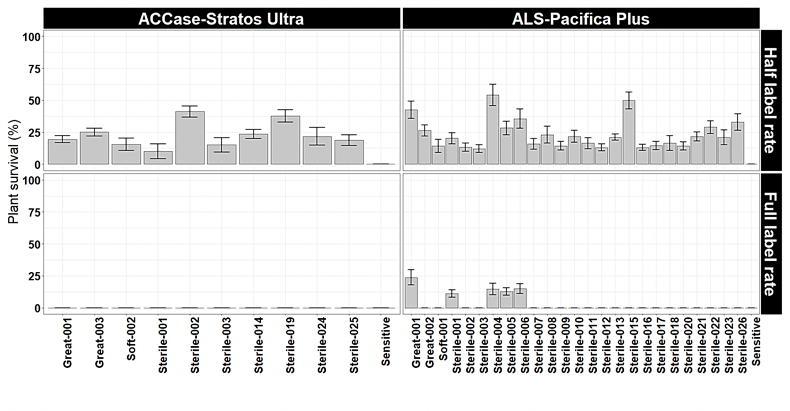

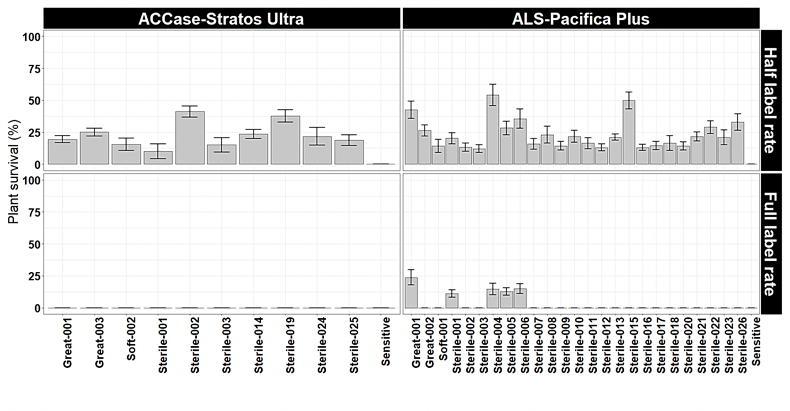

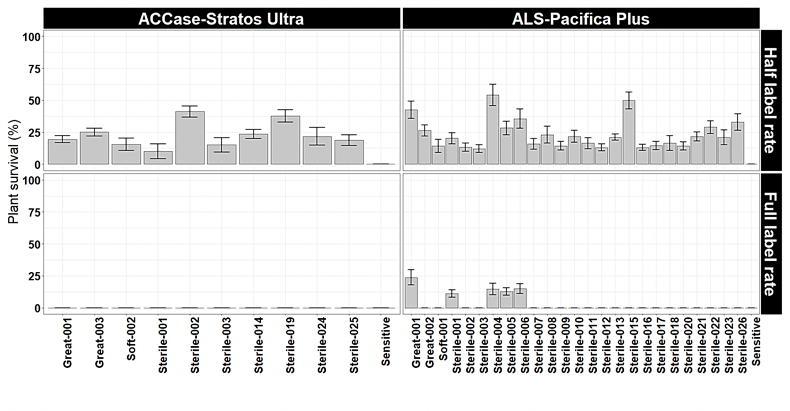

Figure 2: Plant survival (%) for the brome populations tested with ACCase/ALS herbicides at half and full recommended field rates.

Figure 2 shows four sterile brome populations and one great brome population (collected from the triangle mentioned previously) surviving both half- and full-rate of ALS-Pacifica Plus. A further 10 populations survived a half-rate of ACCase-Stratos Ultra, with another 20 populations surving half-rate of ALS-Pacifica.

It is possible that non-target-site resistance (NTSR) might be the cause of the low-level ALS-resistance.

Nevertheless, ACCase-Falcon (half- and full-rate) and Stratos Ultra (full-rate only) as well as ALS-Broadway Star (half- and full-rate) herbicides were highly effective on all brome types, including less sensitive ones, when used at the correct plant growth stage (two- to three-leaf).

Integrated weed management

Managing wild oat and brome populations should utilise chemical control along with cultural/non-chemical methods, rather than relying exclusively on herbicides for control.

Integrated weed management (IWM) options include a range of practices that ultimately disadvantage the weed species and prevent or reduce seed return.

Map infected areas in fields in May/June to guide further actions.

Hand rogue small early-stage infestations or spray off distinct patches before seeds set, especially on headlands for bromes, to prevent seed return.

If resistant wild oats are widespread across fields, whole crop (cutting, baling and removing affected straw) or spray off with glyphosate before seeds start shedding to prevent seed return.

Wild oats that have not already been treated should get priority.

As many sterile brome infestations originate from field margins, establishing a perennial cover or grass margin (Cocksfoot mix and/or Timothy) will provide competition for the grass weeds to slow their growth and reduce seed return.

Such field margins should be mown in the following May and September to encourage grass tillering and prevent the return of brome seeds.

High levels of machinery hygiene are essential to prevent field-to-field spread of weed seeds.

For wild oats, delaying post-harvest cultivations for as long as possible encourages natural losses (predation) of freshly-shed seeds.

Different post-harvest treatments apply to the different bromes, hence correct identification is key. This is critical in direct drill or strip-till situations.

For sterile and great brome, early post-harvest cultivation encourages germination of freshly-shed seeds and the opportunity to spray-off with glyphosate pre-sowing. In other situations, a chopped straw-cover spread evenly may provide adequate darkness and moisture to trigger rapid germination. Note: when brome seeds are left on the soil surface and exposed to light, they can go into dormancy, resulting in delayed germination.For soft, meadow and rye bromes, UK research suggests delaying cultivation (ie leaving seeds on the soil surface) for about a month, which allows for after-ripening and germination to occur, allowing pre-sowing glyphosate control.Wild oats are somewhat different because they can proliferate across all crop establishment systems.

Ploughing helps preserve their dormancy as well as bringing previously buried seeds to the surface. However, spring crops established after direct drilling may reduce wild oat infestations, provided emerged plants are destroyed by glyphosate pre-sowing.

Remember, stale seedbeds in autumn, delayed autumn-drilling or pre-emergence herbicides applied in autumn will not guarantee successful spring wild oats control. However these measures increase crop competitiveness.

Use of other IWM measures (eg planting of more competitive crops/varieties, use of higher than normal seeding rate, etc) are also necessary to reduce the weed seed bank.

Ploughing to 15cm or more is key to preventing brome re-emergence from below their emergence depth.

Sterile brome has become a very serious weed in some fields around the country, especially where min-till is used.

Relative to other weeds, repeated ploughing may carry less risk of bringing up viable brome seeds.

Delayed sowing until the second half of October will help avoid the main autumn flush of bromes.

This technique, followed by multi-year spring cropping, would give effective control in fields with large infestations of sterile and great bromes, as it avoids the peak germination period in autumn.

Chemical control

The recommended field rate of ACCase/ALS herbicides will give good control of susceptible wild oats and bromes when used at the correct plant growth stage (ideally at the two- to four-leaf stage, or before crop GS30). Remember, post-emergence herbicides should be sprayed on a dry leaf of small actively growing plants for maximum efficacy. Where wild oat plants are larger, it is critical to use maximum rates (eg Axial at 0.82l/ha after crop GS30) to achieve a complete kill of susceptible populations, and to reduce the risk of resistance developing.The inclusion of non-cereal break crops like beans and oilseed rape provides an opportunity to use propyzamide (eg Kerb) followed by ACCase-Falcon, Stratos Ultra or Centurion Max at full-field rate to control sterile and great bromes. Avoid having to spray older or larger brome plants that are well past the optimum stage for control, and avoid spraying under stressful conditions. Always conduct resistance testing to determine if your wild oat population is susceptible to ACCase graminicides.

Farms where wild oat populations have confirmed or suspected resistance to ACCase modes of action:

Apply glyphosate on stubbles (at least 1.5l/ha) to control young weed plants before planting.Pre-emergence herbicides (eg Avadex) will offer some control, but plants often escape herbicide treatments due to their sporadic germination patterns.For ACCase-resistant populations, adequate control may initially be achieved using ALS herbicides (eg Pacifica or Broadway).Cultural/non-chemical IWM, such as hand roguing, machinery hygiene, planting of more competitive crops and using higher-than-normal seed rates etc, should be combined with alternative chemistry.Farms where brome populations have less sensitivity to ALS or ACCase modes of action:

Glyphosate use on stubbles (at least 1.5l/ha or where populations are abundant and widespread; use 3.0l/ha to ensure effective kill).Use residual herbicides – timing, conditions and application are key for efficacy.Use ACCase (eg Falcon) and ALS (eg Broadway Star) herbicides at full-field rate for adequate control of less sensitive populations.Cultural/non-chemical IWM, like delayed autumn drilling, multi-year spring cropping, higher seed rates, ploughing and hand roguing are all effective at reducing soil seed bank population.*Dr Vijaya Bhaskar AV is a research officer specialising in grass weeds at Teagasc Oak Park.

The propensity to develop resistance is moderate in wild oats and bromes, but it should not be ignored.In fields having large populations of wild oats and bromes, it is always recommended to use full-rate of ACCase/ALS herbicides for effective control.Use non-chemical and cultural IWM tactics in every field, wherever possible, to preserve effective alternative chemistries.

In Ireland, wild oats and bromes are the two most frequently occurring grassweed species in cereal crops.

Due to the traditional level of spring cereal cropping, fields generally have spring wild oats, but occasionally fields can have a mixed population of spring and winter wild oats.

Wild oat seeds have longer dormancy (more than five years) and higher survival rates on burying than most other grassweeds (eg bromes, blackgrass and Italian ryegrass).Plants can emerge from deeper soil depths (more than 10cm).Plants often escape herbicide applications, due to irregular germination.Among the five types of bromes, sterile brome is the most common and is found mainly at the base of ditches, headlands, field margins as well as within crop fields. Other types like great, soft, meadow and rye bromes are also found locally in many fields.

Sterile and great bromes have similar biology with peak-autumn germination; other types have more protracted emergence.Seeds have a short dormancy (less than two years).Seed numbers decline rapidly (80% to 90% per year) when buried, and seeds do not emerge from more than 10cm deep.Both wild oats and bromes are predominantly self-pollinating and so herbicide resistance is relatively slow to develop compared to outcrossing blackgrass or Italian ryegrass. In recent years, we have identified a number of fields where there is difficulty controlling wild oats and bromes effectively with herbicides.

In this article, I discuss the chemical options available and the type of resistance that is evolving to spring post-emergence ACCase/ALS grassweed herbicides. I also outline integrated weed management (IWM) options for wild oat and brome control. This knowledge is critical to improve our ability to control suspect populations, and to prevent resistance development.

Chemical options

There are a number of ways that we can tackle these grassweeds, both within and outside of the crop to be grown:

Glyphosate before sowing the crop to kill previously emerged plants.Residual herbicides, like pendimethalin (Stomp Aqua), flufenacet (Firebird) or prosulfocarb (Defy) in winter cereals applied pre-emergence (24 to 48 hours after drilling) or early post-emergence (autumn treatment) of the crop and weed, and triallate (Avadex Factor) in winter cereals and spring barley, applied pre-emergence (24 to 48 hours after drilling), offers limited control of bromes and/or wild oats.Remember, tank-mixed residual herbicides (eg Firebird + Defy) or stacked products (eg Firebird Met containing DFF + flufenacet + metribuzin) will be most effective and faster-acting than single actives in controlling critical grassweeds. Also, pre-emergence herbicides applied in autumn are unlikely to provide spring wild oats control.

Use non-ACCase and non-ALS herbicide, eg Kerb (propyzamide) in winter oilseed rape for brome control.Spring post-emergence herbicide (contact-only) options include:Axial (ACCase) for wild oat control in barley or wheat (spring and winter);ACCase products like Falcon, Stratos Ultra or Centurion Max in winter oilseed rape for wild oats and bromes; andALS-Pacifica Plus, Monolith or Broadway Star in winter wheat for wild oats and bromes control.Herbicide resistance and types

Our nationwide grassweed survey has shown that fields with high infestations of wild oats or bromes are more likely to develop herbicide resistance or be less sensitive to herbicides.

From the 100 field populations of wild oats screened to-date, herbicide resistance has been found in 15% of populations, with plant survival from full-rate herbicide applications varying from 25% to 100%. These samples were collected in Wexford, Kilkenny, Cork, Tipperary and Kildare.

Those identified as resistant fell into three different categories (Table 1):

Cross-resistance to all three ACCase actives.Cross-resistance to Axial and Falcon.Falcon-resistance only.These results suggest that herbicides from the same group can behave differently in the same field.

The main mechanism of ACCase resistance is target-site resistance (TSR), with non-target-site resistance (NTSR) being partial or at an early stage.

However, ALS herbicides were highly active on all populations tested, including ACCase-resistant populations, when used at the correct plant growth stage (three- to four-leaf).

With over 100 field populations of bromes tested, only a few populations survived the full-field rate of ALS-Pacifica Plus, with plant survival ranging from 10% to 24%.

There is, however, widespread tolerance among brome types (including sterile, great and soft), collected in the Louth/Wexford/Cork triangle, to half-rates of ACCase-Stratos Ultra and/or ALS-Pacifica Plus, with plant survival from 10% to 50%+, which may be due to repetitive use of reduced field rates.

Figure 2: Plant survival (%) for the brome populations tested with ACCase/ALS herbicides at half and full recommended field rates.

Figure 2 shows four sterile brome populations and one great brome population (collected from the triangle mentioned previously) surviving both half- and full-rate of ALS-Pacifica Plus. A further 10 populations survived a half-rate of ACCase-Stratos Ultra, with another 20 populations surving half-rate of ALS-Pacifica.

It is possible that non-target-site resistance (NTSR) might be the cause of the low-level ALS-resistance.

Nevertheless, ACCase-Falcon (half- and full-rate) and Stratos Ultra (full-rate only) as well as ALS-Broadway Star (half- and full-rate) herbicides were highly effective on all brome types, including less sensitive ones, when used at the correct plant growth stage (two- to three-leaf).

Integrated weed management

Managing wild oat and brome populations should utilise chemical control along with cultural/non-chemical methods, rather than relying exclusively on herbicides for control.

Integrated weed management (IWM) options include a range of practices that ultimately disadvantage the weed species and prevent or reduce seed return.

Map infected areas in fields in May/June to guide further actions.

Hand rogue small early-stage infestations or spray off distinct patches before seeds set, especially on headlands for bromes, to prevent seed return.

If resistant wild oats are widespread across fields, whole crop (cutting, baling and removing affected straw) or spray off with glyphosate before seeds start shedding to prevent seed return.

Wild oats that have not already been treated should get priority.

As many sterile brome infestations originate from field margins, establishing a perennial cover or grass margin (Cocksfoot mix and/or Timothy) will provide competition for the grass weeds to slow their growth and reduce seed return.

Such field margins should be mown in the following May and September to encourage grass tillering and prevent the return of brome seeds.

High levels of machinery hygiene are essential to prevent field-to-field spread of weed seeds.

For wild oats, delaying post-harvest cultivations for as long as possible encourages natural losses (predation) of freshly-shed seeds.

Different post-harvest treatments apply to the different bromes, hence correct identification is key. This is critical in direct drill or strip-till situations.

For sterile and great brome, early post-harvest cultivation encourages germination of freshly-shed seeds and the opportunity to spray-off with glyphosate pre-sowing. In other situations, a chopped straw-cover spread evenly may provide adequate darkness and moisture to trigger rapid germination. Note: when brome seeds are left on the soil surface and exposed to light, they can go into dormancy, resulting in delayed germination.For soft, meadow and rye bromes, UK research suggests delaying cultivation (ie leaving seeds on the soil surface) for about a month, which allows for after-ripening and germination to occur, allowing pre-sowing glyphosate control.Wild oats are somewhat different because they can proliferate across all crop establishment systems.

Ploughing helps preserve their dormancy as well as bringing previously buried seeds to the surface. However, spring crops established after direct drilling may reduce wild oat infestations, provided emerged plants are destroyed by glyphosate pre-sowing.

Remember, stale seedbeds in autumn, delayed autumn-drilling or pre-emergence herbicides applied in autumn will not guarantee successful spring wild oats control. However these measures increase crop competitiveness.

Use of other IWM measures (eg planting of more competitive crops/varieties, use of higher than normal seeding rate, etc) are also necessary to reduce the weed seed bank.

Ploughing to 15cm or more is key to preventing brome re-emergence from below their emergence depth.

Sterile brome has become a very serious weed in some fields around the country, especially where min-till is used.

Relative to other weeds, repeated ploughing may carry less risk of bringing up viable brome seeds.

Delayed sowing until the second half of October will help avoid the main autumn flush of bromes.

This technique, followed by multi-year spring cropping, would give effective control in fields with large infestations of sterile and great bromes, as it avoids the peak germination period in autumn.

Chemical control

The recommended field rate of ACCase/ALS herbicides will give good control of susceptible wild oats and bromes when used at the correct plant growth stage (ideally at the two- to four-leaf stage, or before crop GS30). Remember, post-emergence herbicides should be sprayed on a dry leaf of small actively growing plants for maximum efficacy. Where wild oat plants are larger, it is critical to use maximum rates (eg Axial at 0.82l/ha after crop GS30) to achieve a complete kill of susceptible populations, and to reduce the risk of resistance developing.The inclusion of non-cereal break crops like beans and oilseed rape provides an opportunity to use propyzamide (eg Kerb) followed by ACCase-Falcon, Stratos Ultra or Centurion Max at full-field rate to control sterile and great bromes. Avoid having to spray older or larger brome plants that are well past the optimum stage for control, and avoid spraying under stressful conditions. Always conduct resistance testing to determine if your wild oat population is susceptible to ACCase graminicides.

Farms where wild oat populations have confirmed or suspected resistance to ACCase modes of action:

Apply glyphosate on stubbles (at least 1.5l/ha) to control young weed plants before planting.Pre-emergence herbicides (eg Avadex) will offer some control, but plants often escape herbicide treatments due to their sporadic germination patterns.For ACCase-resistant populations, adequate control may initially be achieved using ALS herbicides (eg Pacifica or Broadway).Cultural/non-chemical IWM, such as hand roguing, machinery hygiene, planting of more competitive crops and using higher-than-normal seed rates etc, should be combined with alternative chemistry.Farms where brome populations have less sensitivity to ALS or ACCase modes of action:

Glyphosate use on stubbles (at least 1.5l/ha or where populations are abundant and widespread; use 3.0l/ha to ensure effective kill).Use residual herbicides – timing, conditions and application are key for efficacy.Use ACCase (eg Falcon) and ALS (eg Broadway Star) herbicides at full-field rate for adequate control of less sensitive populations.Cultural/non-chemical IWM, like delayed autumn drilling, multi-year spring cropping, higher seed rates, ploughing and hand roguing are all effective at reducing soil seed bank population.*Dr Vijaya Bhaskar AV is a research officer specialising in grass weeds at Teagasc Oak Park.

The propensity to develop resistance is moderate in wild oats and bromes, but it should not be ignored.In fields having large populations of wild oats and bromes, it is always recommended to use full-rate of ACCase/ALS herbicides for effective control.Use non-chemical and cultural IWM tactics in every field, wherever possible, to preserve effective alternative chemistries.

SHARING OPTIONS