Ever wonder how grass seed is produced and ends up in your local co-op or merchant? I recently visited the Royal Barenbrug Group in The Netherlands to find out the process involved in producing a new variety of grass seed from start to finish.

Grass variety production is a very long and complicated process, taking up to 15 years from when the initial seed cross takes place to the point where seed is made commercially available.

The breeding process commences with the crossing under controlled conditions of selected parent plants which have positive attributes, such as high yield and disease resistance.

Progeny from these crosses are evaluated, initially as individual plants and then in small plots, over a two- to three-year period where forage yield, nutritional quality and disease resistance can be carefully measured.

The best performing varieties are then put into larger trials and are monitored again in larger plots (10m2) on several locations, where the new grasses are exposed to a range of environmental conditions.

As Barenbrug is a multinational company with grass trials worldwide, test sites are carefully chosen to measure performance under conditions relevant to the target market.

For the Irish market, three main trial sites in England, Scotland and Ireland produce relevant information on forage yield, nutritional quality, persistency, disease resistance and winter hardiness. For the Irish market, Barenbrug has had a long-standing commercial partnership arrangement with AFBI in Co Armagh. Many successful varieties, including Navan, Portstewart and Tyrella, have been bred at this station and marketed in Ireland by Germinal Seeds.

Variety testing

From a distance, all grasses look the same, but a close examination reveals big differences in many agronomic characteristics which can affect productivity and animal performance.

As part of the breeding process, forage yield is measured using small plot harvesters, cutting one plot at a time and accurately weighing the forage produced. Particular attention is given to identifying varieties with good spring growth, especially for countries where early spring grazing is possible.

After cutting, grass samples are taken off to the laboratory for measurement of dry matter content, digestibility, sugar content and fibre. A very important aspect of variety evaluation is the assessment of crown rust and leaf spot diseases and for this the Barenbrug trial site at Evesham in Worcestershire is very important.

AFBI plant breeder David Johnston said: “Grass diseases are immensely important in the southern half of Britain and have a detrimental effect upon sward production and animal performance. There is increasing evidence that diseases are affecting grass plants in Ireland. Therefore we have to be careful to select varieties with improved disease resistance.” Another aspect of variety performance is an evaluation under real farm conditions where new grasses are tested under livestock grazing and silage production.

Even when this extensive testing process is complete, new grass varieties have to be evaluated independently in recommended list trials. Only the very best varieties, which have given consistent performance, are added to the Irish recommended list. So, from the starting point 15 years previously, only about 1% of the breeding material finally makes it through into the marketplace. Hence the very high cost of breeding a new variety, estimated to be over €500,000.

Producing commercial grass seed

Grass seed destined for Ireland is usually produced on arable farms on the coastline of western Europe, Belgium, The Netherlands, France and Denmark. Rien Louwes, international product manager forage with Barenbrug, says: “The company has over 9,000 seed growers worldwide and we give them support with large teams of technical agronomists.”

Production is on a contract basis, but it can be difficult to persuade growers to produce grass seed when cereal prices are high. The production of commercial seed goes through four generations, namely, breeders, pre-basic, basic and certified.

At each stage, careful attention has to be paid to ensure that crops are free from broad-leaved weeds and ‘off types’. For example, if Italian ryegrass plants are detected in a crop of perennial ryegrass, the crop would not be certified and would have to be destroyed.

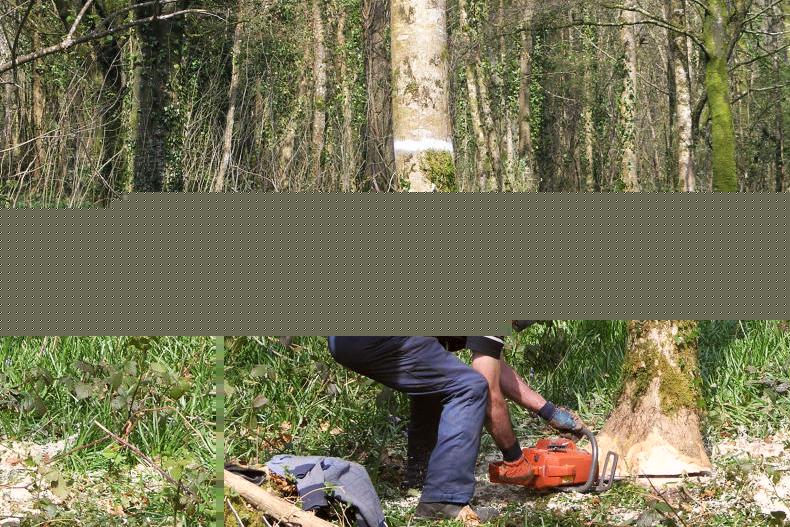

Grass seed harvesting takes place in July or August each year and most crops are cut down and left to dry in a swath, prior to being picked up and threshed with a combine fitted with a pick-up header.

The harvested seed has to be dried down to about 12% moisture content immediately after harvest, as any heating of seeds would have a negative effect upon germination. Grass seed production is a high-risk business requiring flat, open fields in areas which do not suffer from heavy rainfall in summer.

Cleaning

Quality coming from farms is really dependent on the weather conditions during harvest. In a dry summer, almost everything is at a low moisture content and is easy to process. However, in wetter harvests, samples occasionally require extra drying, adding to the production cost.

All the weed seeds and chaff are separated from the grass seed using sieving machines and indented cylinders which remove straws, small seeds, chaff and weed seeds. Waste can amount to 5% to 20% of the total batch brought in, depending on the species and the farm.

Farmers are paid a base price of €2 to €2.50 per kg of grass seed produced, with bonuses given on quality and penalties imposed for excess waste.

A sample is sent to a laboratory and is tested for purity and germination. Based on the results of this test, the lab will give the batch a certificate. The batch has to meet EU standards; otherwise it can’t be traded and may have to be destroyed.

All varieties are stored separately in large wooden boxes on the premises. Some varieties can be stored over a few years, depending on sales. If stored for over a year, the batches have to be re-analysed to make sure quality did not deteriorate during the period.

Barenbrug has a bagging facility on site which allows it to transfer each variety from the stores and mix it with other varieties. When the varieties are mixed, they are then placed into the one-acre bags. Some larger companies like Germinal Seeds in Ireland buy big bags of straight varieties and mix and bag them into ley mixtures for sale onto Irish farms.

Irish-produced grass seed

Grass seed is no longer produced by Irish farmers for a number of reasons.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, growers received an indirect production subsidy for the quantity grown, via the seed assembler, from the EEC. This was paid on a tonnage basis and could therefore contribute to the crop margin in a very clear way. However, in 1993 this price premium was merged into the Area Aid Payments following the MacSharry reforms.

This hid the traditional subsidy as any indirect benefit equally applied to cereal profitability as it did to grass seed profitability and growers left the grass seed business.

Basically, it was far more profitable and less risky to produce grain with the area aid support compared with producing grass seed. There was no longer an advantage to produce grass seed.

While grass seed was an excellent break crop on tillage farms, its production was less appealing by the mid-1990s.

But the market was also difficult, with gluts and low prices common, and the industry became less appealing to both growers and seed assemblers.

Given the great difficulties associated with harvesting the crop and saving hay, growers drifted away. Rain at harvest could beat the crop into the ground, making it very difficult to harvest. It seemed easier for continental growers to produce grass seed because they usually enjoy longer periods of settled weather.

SHARING OPTIONS