Motor neurone disease (MND) is one of the groups of diseases that affects the nervous system,” says Beaumont Hospitalbased Prof Orla Hardiman.

“Our youngest patient was 15 and the oldest over 90 but the peak age of onset in Ireland is the late 60s. It’s also a little bit more common in men than women but we don’t know why.”

Motor neurone disease is catergorised as one of the neurodegenerative diseases – a group that includes Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. “It’s where the brain develops normally but at some point in adulthood starts giving trouble,” she says. “The brain is a really complicated computer system and we are only starting to learn how it works.”

Neuro-degenerative diseases are the final frontier in medicine, she says. “We don’t really have a good handle as yet on the reasons why people who are perfectly healthy up to mid-life or late mid life are suddenly affected.”

The cell degenerations in MND happen in systems so symptoms can vary from person to person depending on what area of their brain is affected first.

“It’s usually the system that controls movement that starts giving trouble,” Prof Hardiman says.

“It could start with a foot drop or cramping of the hands or being unable to do fine-finger movements like fastening zips or doing up buttons.”

With others, speech or swallowing can be affected first. With others it’s their breathing. Behaviour (personality) can change in some cases too.

MND became Prof Hardiman’s specialty after she met so many patients with the disease in her clinic. Some 80% of those with the condition in Ireland are treated in Beaumont hospital.

“These people had huge needs,” she says. “I wanted to help them have a better quality of life and to cope with their disability better. I feel privileged to be able to help.”

“About 70% live less than 1,000 days from their first symptoms - that’s less than three years,” she says, “30% of those with MND live much longer. Andy McGovern (see right), for example, has lived for over 30 years with it, defying all the odds, so you never know.

“We are working very hard trying to understand the factors that will predict whether someone is going to have a short or long trajectory to their illness. If you have thinking trouble (cognitive impairment) it tends to progress more rapidly, we find, because more of the brain is affected.”

About 40% of people with MND will have a form of dementia. Another 25% will experience subtle changes that get worse over time. About 10% of those with it will have a family history of it.

MND often hits people in the prime of life, she adds.

“Those who get it are often still working and it affects them, their families and communities. Their needs are many because so many aspects are affected – mobility, hand movement, swallow, speech ... The person has to change the way they live, their environment, the way they get around.

“That’s why they need to be able to access a very broad-based multidisciplinary form of care.”

Those with MND need medical cards from the time of diagnosis, she believes. “It’s becoming increasingly difficult to get them and some patients, diagnosed with MND, have had their cards withdrawn. This has widespread repercussions for patients.

“If you don’t have a medical card you don’t get an occupational therapist, if you don’t get that you can’t get equipment for your home, if you don’t get that your quality of life declines significantly. We must remember what the person is trying to cope with.

“The person who has been diagnosed is not only trying to come to terms with having a life threatening disease that has no cure, they are also having to negotiate a very fractured, dysfunctional health system. To me it’s a bureaucratised system that is unfriendly and unsympathetic.”

MND is not a common disease, she says, so those with it should be given this support.

“Only about 100 people are newly diagnosed each year.”

Diseases like MND, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s are very difficult diseases to cure, she says. “That’s because you can’t take a piece of brain out like you can take out a piece of cancer. We are optimistic though.

“Already drugs are more sophisticated than they were five or 10 years ago. We can take hope from the fact that so many people are working together to find a cure and better treatment.” CL

For more see www.imnda.ieAgainst the Odds, €14.99, is available in bookshops, online on www.imnda.ie and at www.londubh.ie

ANDY’S STORY

Andy McGovern lives in Cloone, Co Leitrim, and is now 80 years of age.

The father of six was diagnosed with MND in 1976 – 37 years ago.

He has no use in his arms but he believes in making the most of life.

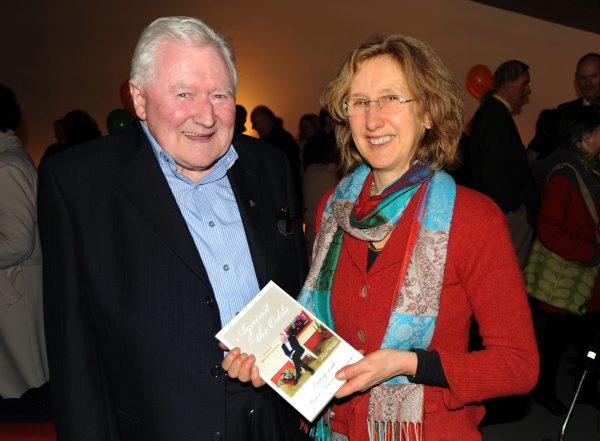

He is the author of several books including his most recent Against the Odds: Living with MND.

A JCB driver for many years, he was shaving one Saturday night when his hand fell from his cheek. He tells us what happened: “I thought one of the children had pulled at my elbow but nobody was near me. I ignored it but over time I noticed my arm muscles were getting weak. I tried not to think about it but I was diagnosed in 1976.

“The last thing I wanted to do was give up work. Towards the end I had to stand on the back of the digger to operate it. I could work the levers when my hands were hanging down straight but not when I was sitting down.

“Sometimes I had to bring one of the children with me, too, in case I had a breakdown and needed to put a wrench on a nut. My down strength was perfect but I’d nothing coming up.”

After diagnosis, Andy got splints made for his wrists and it was in 1996, when referred to the Central Remedial Clinic, that he started writing. “A technician there showed me how to use an old-time computer,” he says.

“He fitted me up with two foot controls so I was able to move the mouse across the screen. The keyboard was on the bottom of the monitor and by kicking or pressing with my foot I could move the letter up to the top of the screen to begin to make a word. It took me a whole day to write my name ‘Andy’. I felt like giving up because it was so tedious but the technician encouraged me and brought the computer down to my house. I got faster as time went on.

“My first book was They Laughed At This Man’s Funeral – a biography of my father that took me three years to write with no spell-checker and only a primary school education.”

Later on Andy got voice recognition software and was then able to write e-mails and keep in touch with people. “Eighteen months, ago I decided to write my own story, Against the Odds: Living with MND, and Londubh have published it,” he says. “It’s about growing up on a Leitrim farm and what happened in my life.

“Writing the book was a way of giving something back and my royalties will go to the Irish Motor Neurone Disease Association (IMNDA).

“I manage as best I can and am glad to have great family back up. There may be a cure someday but it would be great if they could find something to arrest the progress of it at least.”

Andy credits his ease of mind with an experience in Lourdes. “The first time I went I prayed for a cure but I wasn’t cured so I lost belief and felt infuriated but I went back to Lourdes 10 years later.

“It was a statement from a carer that changed things for me. He was walking with me, fast, to catch up on our group and he said ‘you’re the fittest invalid in Lourdes’. He was paying me a tribute but I felt like I’d been punched in the stomach.

“I never thought I was an invalid, I hated that word but the gift of acceptance came slowly after that night. I wasn’t fighting the disease any more – I had found my inner person. There’s a second person in everybody. Most people don’t have to dig deep to find that person. I found I could now take on challenges and achieve them. I climbed Croagh Patrick after that without a stick, twice. I wrote my book. I did things beyond my wildest dreams.

“I started to look at what I had left, not what I had lost. I’m thankful that I’ve had wonderful control of my speech so far and my intellect. I know my disability has lifted and ignited that. I’m doing things now that I would never have done if I was able-bodied. An active brain trapped within a useless body – that’s what MND is.

“While I can’t use my hands or arms, I can still go out and walk and I’m happy with the life I have and the abilities I’m left with and with my computer – without that I’d be lost.”

SHARING OPTIONS