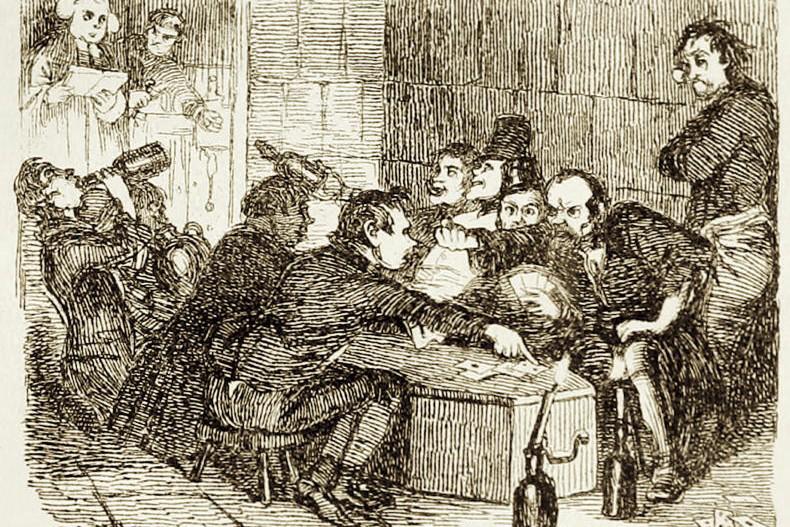

In times gone by, passing time over the cold, long and dark nights of winter consisted of gatherings, big and small, and of people playing cards. From public houses, rambling houses and shebeens to police barracks, presbyteries and boarding schools, the central focus of amusement and communal distraction was nothing more than a simple deck of playing cards.

There were many card games, ‘Beggar my Neighbour’, ‘Old Maid’, ‘Snap’, ‘Thirty-three’ but by far the most popular was known as ‘Twenty-five’ (along with its variations of ‘Forty-five’ and ‘One hundred and ten’.) This distinctively Irish card game reaches back into our medieval past. In Irish, it was known as ‘Mádh’ (trump/fortune) or ‘Mám’ (hand) and in English ‘Five Cards’ and ‘Spoil Five’ and involved an intricate competitive process of placing the best trump to win each ‘trick’.

In truth, anyone who has played this game knows it was more about stopping others from reaching the numerical target and often led to barely disguised stares of steaming vitriol and major fallings-out.

Customary play

With a deck of 52 cards, the maximum number who could play was 10. It was customary to play with a partner and most often a game consisted of four to eight people.

Cards might be played at any idle moment when any convenient flat surface presented itself including the tops of beer barrels, the edge of a donkey’s butt outside the creamery and even the lid of the deceased’s coffin at a wake. Cards were regularly played at home, but often greater fun and gambling was to be found at pubs, shebeens and rambling houses.

Some designated ‘card houses’ operated their own set of rules with set times, starting at seven o’clock and stopping at 10, lest the playing went on to the small hours, but in many cases the card playing continued until the dawn.

It was thought to be very bad luck to carry your own deck of cards to a card game and anyone carrying cards home late at night, might be challenged to a game with the devil at the crossroads. As always, after a good shuffle, someone had to cut the cards and if the dealer kept the deck in their hand, rather than placing them on the table, it was thought that you could steal their luck.

A cartoon of the ubiquitous turkey drawn many years ago by Shane’s late father Tadg for his newspaper column ‘Wise and Otherwise’ in the Evening Echo newspaper.

Each player was dealt five cards, traditionally always dealt in threes and twos. The best trump cards were the five of trumps, known as the ‘five fingers’, followed by the jack, joker, the ace of hearts and the ace of trumps. These were followed by the king and the queen and then by the lowest in black and the highest in red. Depending on the cards you were dealt and your level of skill, notions of luck abounded.

Anyone on a run of bad luck might counter it by walking around their chair a few times or going outside and walking around the house.

Equally, their luck depended on who they were sitting beside and if that person had recently killed an animal. The good luck and bad luck variations were endless.

In the 19th century, shebeens promoted their trade by offering a leg of mutton, a batch of herrings, a fat turkey or a bottle of whiskey to be played for by enthusiastic gamblers. Equally, it was common in designated rambling houses, that the owner would ‘put up’ the runt of a litter of banbhs, a pair of old hens or an aging goose that did not sell at market.

The tradition has continued up to recent times with ‘gambles’ and ‘turkey drives’ and the prize of a fattened turkey being an essential part of the run up to Christmas.

There was a real added sense of triumph and heightened social status if you were the one to win the bird for the festive dinner. Pubs and clubs all over the country enticed the Christmas custom and charity fund-raisers with games of forty-five and New-York-Dressed turkeys at their centre.

I heard recently of one roguish card-player staggering in home from the pub at two o’ clock on Christmas morning. He was of the inebriated opinion that the turkey slung over his shoulder, that he had just won, would quickly quell his wife’s ire.

As he proudly marched in the front door, he unceremoniously tripped on the threshold. In a bizarre catapulting, his momentum propelled the heavy turkey forward and he found himself slaloming, turkey first, at full arm’s stretch along the polished linoleum kitchen floor.

Needless to say, his turkey luck had instantly deserted him.

Shane Lehane is a folklorist who works in UCC and Cork College of FET, Tramore Road Campus. Contact: slehane@ucc.ie

In times gone by, passing time over the cold, long and dark nights of winter consisted of gatherings, big and small, and of people playing cards. From public houses, rambling houses and shebeens to police barracks, presbyteries and boarding schools, the central focus of amusement and communal distraction was nothing more than a simple deck of playing cards.

There were many card games, ‘Beggar my Neighbour’, ‘Old Maid’, ‘Snap’, ‘Thirty-three’ but by far the most popular was known as ‘Twenty-five’ (along with its variations of ‘Forty-five’ and ‘One hundred and ten’.) This distinctively Irish card game reaches back into our medieval past. In Irish, it was known as ‘Mádh’ (trump/fortune) or ‘Mám’ (hand) and in English ‘Five Cards’ and ‘Spoil Five’ and involved an intricate competitive process of placing the best trump to win each ‘trick’.

In truth, anyone who has played this game knows it was more about stopping others from reaching the numerical target and often led to barely disguised stares of steaming vitriol and major fallings-out.

Customary play

With a deck of 52 cards, the maximum number who could play was 10. It was customary to play with a partner and most often a game consisted of four to eight people.

Cards might be played at any idle moment when any convenient flat surface presented itself including the tops of beer barrels, the edge of a donkey’s butt outside the creamery and even the lid of the deceased’s coffin at a wake. Cards were regularly played at home, but often greater fun and gambling was to be found at pubs, shebeens and rambling houses.

Some designated ‘card houses’ operated their own set of rules with set times, starting at seven o’clock and stopping at 10, lest the playing went on to the small hours, but in many cases the card playing continued until the dawn.

It was thought to be very bad luck to carry your own deck of cards to a card game and anyone carrying cards home late at night, might be challenged to a game with the devil at the crossroads. As always, after a good shuffle, someone had to cut the cards and if the dealer kept the deck in their hand, rather than placing them on the table, it was thought that you could steal their luck.

A cartoon of the ubiquitous turkey drawn many years ago by Shane’s late father Tadg for his newspaper column ‘Wise and Otherwise’ in the Evening Echo newspaper.

Each player was dealt five cards, traditionally always dealt in threes and twos. The best trump cards were the five of trumps, known as the ‘five fingers’, followed by the jack, joker, the ace of hearts and the ace of trumps. These were followed by the king and the queen and then by the lowest in black and the highest in red. Depending on the cards you were dealt and your level of skill, notions of luck abounded.

Anyone on a run of bad luck might counter it by walking around their chair a few times or going outside and walking around the house.

Equally, their luck depended on who they were sitting beside and if that person had recently killed an animal. The good luck and bad luck variations were endless.

In the 19th century, shebeens promoted their trade by offering a leg of mutton, a batch of herrings, a fat turkey or a bottle of whiskey to be played for by enthusiastic gamblers. Equally, it was common in designated rambling houses, that the owner would ‘put up’ the runt of a litter of banbhs, a pair of old hens or an aging goose that did not sell at market.

The tradition has continued up to recent times with ‘gambles’ and ‘turkey drives’ and the prize of a fattened turkey being an essential part of the run up to Christmas.

There was a real added sense of triumph and heightened social status if you were the one to win the bird for the festive dinner. Pubs and clubs all over the country enticed the Christmas custom and charity fund-raisers with games of forty-five and New-York-Dressed turkeys at their centre.

I heard recently of one roguish card-player staggering in home from the pub at two o’ clock on Christmas morning. He was of the inebriated opinion that the turkey slung over his shoulder, that he had just won, would quickly quell his wife’s ire.

As he proudly marched in the front door, he unceremoniously tripped on the threshold. In a bizarre catapulting, his momentum propelled the heavy turkey forward and he found himself slaloming, turkey first, at full arm’s stretch along the polished linoleum kitchen floor.

Needless to say, his turkey luck had instantly deserted him.

Shane Lehane is a folklorist who works in UCC and Cork College of FET, Tramore Road Campus. Contact: slehane@ucc.ie

SHARING OPTIONS