G van Beek & Zn was founded in 1977 and has grown to become one of the largest producers of calf housing and equipment in the world.

Not only does the company manufacture and construct calf houses, but it also has the contract to rear 50,000 veal calves every year. When constructing a veal house, the company can complete the entire project, bar the plumbing, electrics and the ventilation system.

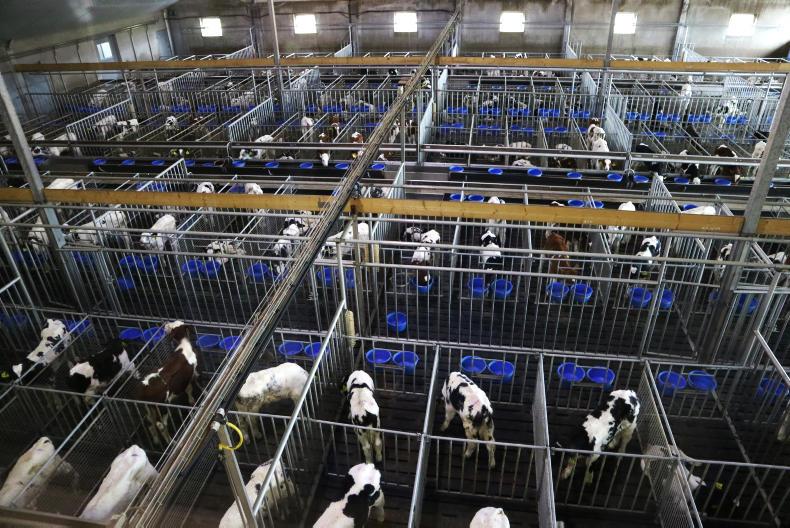

Peter Smit from G. van Beek & Zn brought the Irish Farmers Journal to the company’s farm which has the capacity to hold 1,200 calves under one roof. The farm is used as a research and demonstration facility for potential buyers of the company’s products.

When calves enter the shed they spend three weeks in the individual pens. These are 1m wide by 1.3m long. The regulations in the Netherlands state pens must be a minimum of 800mm by 1.3m, but as this shed is used as a demonstration farm and for research purposes, larger sizes were chosen.

When calves are able to drink milk without any assistance, they go into group pens of eight calves. They stay there until fit for slaughter.

There are two types of veal production systems. Rosé veal is where calves are slaughtered at eight months. Up to this point calves will have been fed a diet of milk and solid feed. Calves intended for rosé veal will receive milk for the first 10 to 12 weeks of life.

At this point they will go off milk and on to a solid feed diet where they receive a mixture of concentrates and straw.

In white veal production, calves are slaughtered at 26 weeks having been fed a diet consisting mostly of milk, generally fed twice a day.

On the farm, white veal calves will have a target liveweight at slaughter of about 260kg. This translates to a carcase weight of 160kg, according to Peter. The target for rosé veal is to have a liveweight at slaughter of about 300kg, due to the increased age, which equates to a carcase of approximately 190kg.

From sampling veal, I don’t believe it is the taste that is holding it back

According to Peter, veal prices generally fluctuate around €5/kg in the Netherlands, which would give a white veal carcase a value of about €800 while a rosé veal carcase could fetch about €950.

The main health problems that occur in veal sheds, according to Peter, are respiratory issues, which he puts down to the range of farms calves can come from.

Calf house design

The shed is divided into two independent sides.

One side is fitted with conventional timber slats while the other side is fitted with Easyfix rubber mats on top of the timber slats.

This is done to help reduce ammonia emissions from the calves’ urine as the urine will flow quicker off the mats into the tank underneath. It is also done to increase calve comfort and animal welfare.

The difference in the smell of ammonia between the two sides of the house was staggering, with the side of the shed fitted with rubber mats having a greatly reduced smell.

Another key aspect of the design of the calf houses is the dung slider in the shallow tanks under the calves. It is similar to a dung scraper in a passage except it is only used to collect the dung and not the urine. The urine is drained off in a channel due to a 4% fall in the floor of the tank. This helps reduce the smell of ammonia.

According to Peter the entire system, the dung sliders and the rubber mats, have the potential to reduce ammonia emissions by between 30% and 40%.

“An average veal farm would have between 600 to 700 calves at any one time,” said Peter (pictured), “however one of the key issues is the disposal of manure.” As an example Peter outlined that 1,000 calves slaughtered for rosé veal production will produce about 4,000 m3 of manure. This type of a system can be run on 2ha to 3ha but then the big issue is the disposal of the waste. According to Peter it can cost between €17 and €18 per m3 to dispose of the manure.

“An average veal farm would have between 600 to 700 calves at any one time,” said Peter (pictured), “however one of the key issues is the disposal of manure.” As an example Peter outlined that 1,000 calves slaughtered for rosé veal production will produce about 4,000 m3 of manure. This type of a system can be run on 2ha to 3ha but then the big issue is the disposal of the waste. According to Peter it can cost between €17 and €18 per m3 to dispose of the manure.

“This why the slider system would be such an advantage for a farm like this where there is such a small amount of land available as it could reduce the amount of manure that would need to be disposed of,” he said.

The disposal of manure is becoming an issue on a lot of intensive farms in the Netherlands, including pig farms. We also visited a 1,000-sow unit where the farm was spending €140,000 per year on labour while the cost of disposing of the manure was €200,000 a year.

For the calves, the thick fraction of the manure takes up approximately 25% to 35% of the total depending on the system operated, with rosé veal having a higher percentage than calves being fed for white veal. The other 65% to 75% is urine. Being able to separate the two could help to reduce the cost of disposing this waste.

The vast majority of land in the Netherlands is under intensive agriculture so there is just not the land base available to spread all of the manure. For this reason, disposal then becomes an issue.

Veal can be a divisive topic but, with more than 41,000 calves going to the Netherlands from Ireland in 2017 in the form of live exports according to Bord Bia figures. The majority of these are for veal production.

There is no denying the significance the sector has for Irish agriculture.

The need for this outlet will only grow with the continued expansion of the dairy industry leading to more calves on the ground.

Any potential market for these calves needs to be explored.

The question does have to be asked whether the option exists to develop a veal industry in Ireland, with the produce then exported.

It would not be beef farming in a conventional sense and would be more akin to pig or poultry production, with intensive indoor finishing. However, with beef farmers’ incomes struggling, it could provide a profitable enterprise.

Mentality change needed

For an industry to develop it would require a change in mentality for livestock farmers, but it is in consumers where the real change would first have to happen.

Another stumbling block to the development of a veal industry is that there are no large-scale processing facilities for calves in Ireland.

A large amount of our surplus calves from the dairy industry are already finding their way to the continental veal market through the Netherlands. If we could produce and export carcases instead of calves, this could develop into a very profitable industry for farmers, while also providing yet another outlet for dairy-bred calves. However, the image of Irish dairy farming would change if we had our own veal market.

SHARING OPTIONS