Bluetongue has been a latent threat to the Irish livestock sector for close to 20 years now. At the time of writing, two cows from a dairy herd in Co Down have been confirmed with the virus, and a further 44 cases are suspected within the same herd.

We hope that this outbreak will be contained at source. As it stands, the Republic of Ireland has not as yet had a case, and remains 100% bluetongue-free.

For farmers north of the border, arrangements allowing livestock to come south for slaughter remain in place currently. This is hugely important, particularly for the sheep sector.

There are some grounds for cautious optimism that the bitter cup of a major bluetongue outbreak may not have to be drank from just now. That is because temperatures, particularly at night, have plummeted this week, with frost widespread. That would minimise the number of midges active and in circulation, reducing the risk of further cases.

Even in a best case scenario, now that cases have been diagnosed on the island, we have had a sharp reminder of just how consequential a significant bluetongue outbreak would be. The immediate effect would be to compromise the live export trade from the area affected by the outbreak, affecting weanlings.

But the autumn sales are winding down, the volume of animals is on the wane and domestic demand would cope fine if the exporters were absent from mart rings. There might be an impact on price, but nothing catastrophic.

The real problems would begin in two months’ time, when the spring calving season begins. The impact on calf exports of bluetongue cases across a significant area of the country is too much to contemplate.

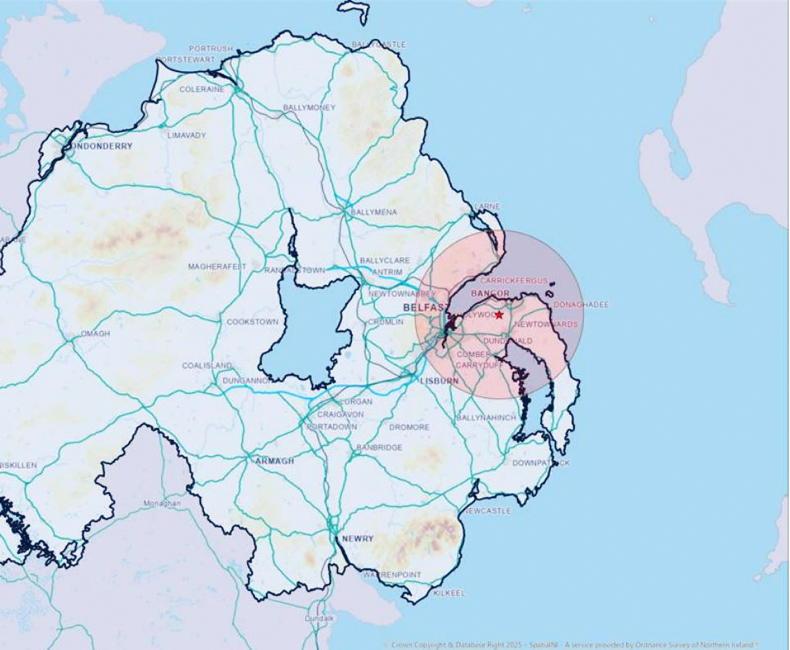

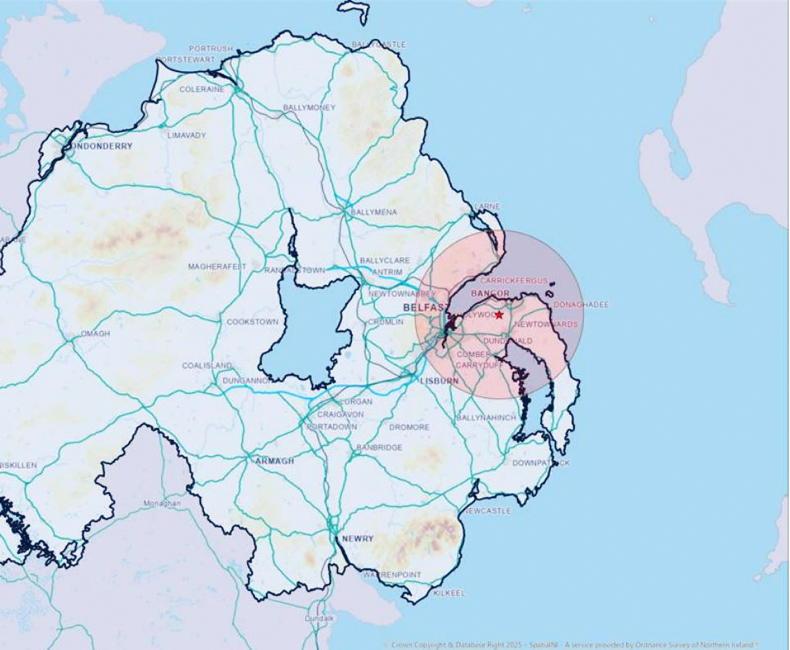

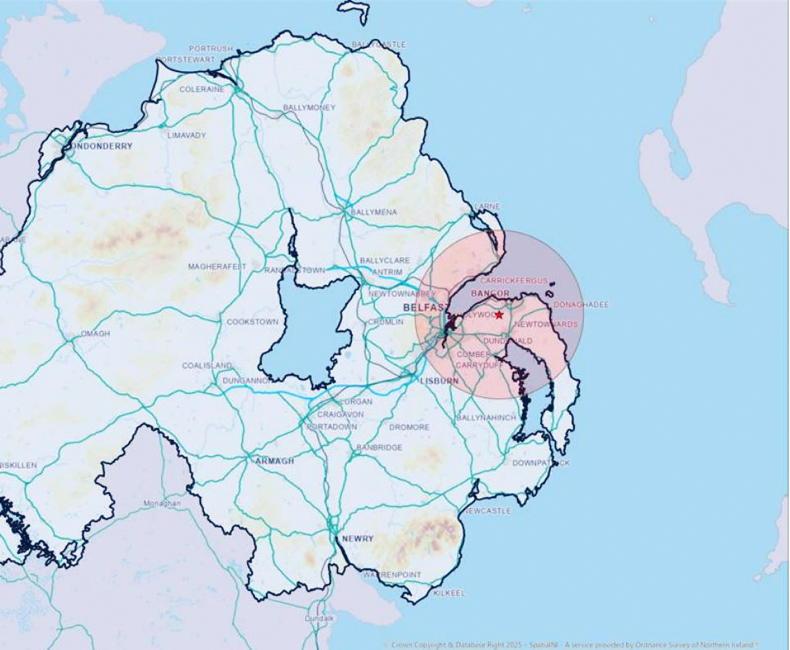

A person shall not move any susceptible species on to or off premises in the zone except under the authority of and in accordance with the conditions of a licence granted by DAERA. / DAERA

And yet contingencies must be put in place. Discussions with our trading partners, in particular the Dutch and French, should be ongoing at the highest levels, so that we have an understanding of how we can keep export lines open.

At the same time, to minimise the potential of bringing bluetongue to our shores, perhaps some import restriction is required, and not just from currently affected bluetongue regions. A ban might be counterproductive in the long term, but what about a quarantine on animals brought into the country for breeding?

Have them remain in lairage for the necessary minimum period while a blood test confirms they are free of the virus. It would minimise the inward traffic, and might serve to remind all farmers to act in the interest of the public good.

In the meantime, spare a thought for the farmers around the current confirmed cases. Down and Louth farmers suffered hugely during the foot and mouth outbreak in 2001, particularly down the Cooley Peninsula.

Hopefully they, and all of us, will be able to celebrate Christmas in the knowledge that bluetongue, for now, has been repelled from the little rock we all share.

Bluetongue has been a latent threat to the Irish livestock sector for close to 20 years now. At the time of writing, two cows from a dairy herd in Co Down have been confirmed with the virus, and a further 44 cases are suspected within the same herd.

We hope that this outbreak will be contained at source. As it stands, the Republic of Ireland has not as yet had a case, and remains 100% bluetongue-free.

For farmers north of the border, arrangements allowing livestock to come south for slaughter remain in place currently. This is hugely important, particularly for the sheep sector.

There are some grounds for cautious optimism that the bitter cup of a major bluetongue outbreak may not have to be drank from just now. That is because temperatures, particularly at night, have plummeted this week, with frost widespread. That would minimise the number of midges active and in circulation, reducing the risk of further cases.

Even in a best case scenario, now that cases have been diagnosed on the island, we have had a sharp reminder of just how consequential a significant bluetongue outbreak would be. The immediate effect would be to compromise the live export trade from the area affected by the outbreak, affecting weanlings.

But the autumn sales are winding down, the volume of animals is on the wane and domestic demand would cope fine if the exporters were absent from mart rings. There might be an impact on price, but nothing catastrophic.

The real problems would begin in two months’ time, when the spring calving season begins. The impact on calf exports of bluetongue cases across a significant area of the country is too much to contemplate.

A person shall not move any susceptible species on to or off premises in the zone except under the authority of and in accordance with the conditions of a licence granted by DAERA. / DAERA

And yet contingencies must be put in place. Discussions with our trading partners, in particular the Dutch and French, should be ongoing at the highest levels, so that we have an understanding of how we can keep export lines open.

At the same time, to minimise the potential of bringing bluetongue to our shores, perhaps some import restriction is required, and not just from currently affected bluetongue regions. A ban might be counterproductive in the long term, but what about a quarantine on animals brought into the country for breeding?

Have them remain in lairage for the necessary minimum period while a blood test confirms they are free of the virus. It would minimise the inward traffic, and might serve to remind all farmers to act in the interest of the public good.

In the meantime, spare a thought for the farmers around the current confirmed cases. Down and Louth farmers suffered hugely during the foot and mouth outbreak in 2001, particularly down the Cooley Peninsula.

Hopefully they, and all of us, will be able to celebrate Christmas in the knowledge that bluetongue, for now, has been repelled from the little rock we all share.

SHARING OPTIONS