Larry Rosenbohm is a fifth-generation Missouri farmer who has experienced much of this change. With distant family connections in both Ireland and Germany, the Rosenbohm family settled in the plains of Nebraska in the early 1800s. By 1924, they had traded their 3,000-acre farm in Nebraska for 338 acres in the much more fertile region of northwest Missouri, where the family still live and farm today.

Larry Rosenbohm is a fifth-generation Missouri farmer who has experienced much of this change. With distant family connections in both Ireland and Germany, the Rosenbohm family settled in the plains of Nebraska in the early 1800s. By 1924, they had traded their 3,000-acre farm in Nebraska for 338 acres in the much more fertile region of northwest Missouri, where the family still live and farm today.

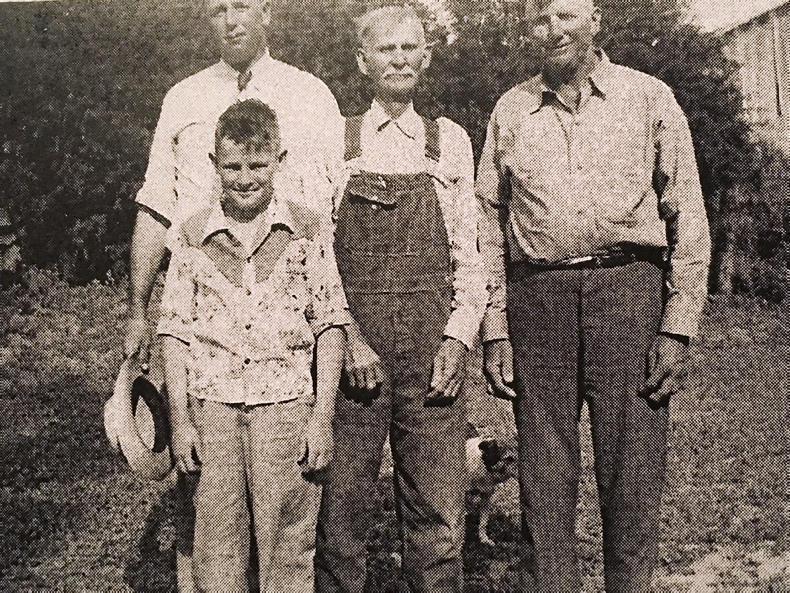

Four generations of Rosenbohms: Larry aged 11 (front) in 1949 and behind him his father George Rosenbohm; great-grandfather, Menne Rosenbohm and grandfather, John W. Rosenbohm.

1930s

Larry was born in 1938, just between the end of the Great Depression and the economic boom of World War II. The Great Depression hit the Midwest region of the US particularly hard, as it followed a period of economic growth, high commodity prices, record yields and farm expansion.

The average farm size at the time stood at 167 acres. The slowdown in the economy, which coincided with an oversupply of grain, low commodity prices, prolonged periods of drought and high debt burdens, proved disastrous for farmers in this region. For example, Chicago wheat fell from $1.40/bushel (€42.52/t) in 1929 to just 49 cents/bushel (€14.88/t) in 1931.

The consequences of the economic meltdown caused untold hardship for millions in the Midwest. Many farms were unable to raise crops or animals and some 750,000 of the 6,295,000 farms in the US were lost through bankruptcy and foreclosure.

Larry explained that they narrowly escaped losing the farm during this time due to an interest-only deal struck by his late grandfather and their credit lender.

“The 1930s was a bad time – everyone was poor. But they didn’t complain about it, they did what they had to do.”

With the onset of higher commodity prices, increased farm mechanisation and adoption of hybrid corn (maize) varieties, US farming began to emerge from that difficult period and come to grips with the new farming landscape.

1940s to 1950s

A young boy in the early 1940s, Larry recalls how his grandfather and father’s four work horses were made redundant when two John Deere hand-start tractors came on to the farm. These then carried out most of the heavy work.

During this period, the productivity of US agriculture rose dramatically alongside the first real use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides.

Grain prices were high, $1.29 to $1.53/bushel (€39-46/t) for corn, due to high food demands from a war-torn world. In the early 1940s, US farm incomes rose significantly.

By this stage, the family was raising livestock, including beef cows, hogs and dairy cows. They grew corn to feed the animals. They also began to grow the farm by purchasing small parcels of land. Land prices ranged from $40 to $60/acre (€33 to €50/ac) at that time.

By the mid-1940s, the majority of corn in the area was harvested using tractor-mounted machines.

“When harvesting corn at that time, most people used a pull-type one-row Woods picker, but there was still a few people doing a bit by hand. The picker took in the whole ear, but it left the husks on the cob. It was a great improvement in efficiency, as well as not being nearly as tiring as hand-picking.”

Electricity arrived to the farm in the late 1940s under the Rural Electrification Act. Larry recalls the impact this had on farming businesses. “It sure made life a lot easier – kerosene lanterns became a thing of the past.” An example of this was in 1952 when they bought their first milking machine for their small dairy herd.

As the decade progressed, the sector continued to make huge advancements through access to new technologies, including new pesticides. And this was despite oversupply and depressed prices, which resulted from the post-WWII agricultural boom.

“When 2,4-D came along in the late 1940s and early 1950s, it was a tremendous help for broad-leafed weed control,” Larry stated.

Conventional soya beans first made their way to the fields in the early 1950s and were quite profitable at between $1.8 and $1.9/bushel (€55 to €58/t) with yields of 20 bushels per acre yield (0.5t/ac). By the mid-1950s, Allis-Chalmers tractors were used for all of the farm’s field work.

Having married his college sweetheart Janet in 1958, Larry then stared a family of his own.

1960s to 1970s

Following the passing of Larry’s grandfather in 1963, Larry and his father continued their working partnership until the untimely passing of his father in the late 1970s.

During this period, US farm output had increased by 35% compared with the 1950s and output would have risen even more if there had not been Federal production control programmes in place.

These production gains were achieved with 11% less cropland and 45% fewer man-hours than in 1950, but with nearly twice as much fertiliser.

By 1969, Larry was using 3020 John Deere tractors and a John Deere 45 combine with a two-row corn head for harvesting. By the 1970s, he had upgraded to a John Deere 55, which was the first combine to have a cab fitted.

The 1970s were very profitable for grain, Larry stated. Helped by increased exports, most notably the sale of over 10 million US tonnes of grain (mainly wheat and corn) to the Soviet Union in 1972, corn and soya bean prices rose to $2.38/bushel (€72/t) and $7.23/bushel (€220/t) respectively. This drove further farm expansion.

New pesticides, such as triathlon and atrazine, helped lower the cost of production and, by this stage, 95% of US farmers were growing hybrid corn.

Throughout this period, Larry grew the farm size by acquiring smaller farms in the area for between $150 and $1,315/ac (€125 and €1,093/ac).

1980s to 1990s

The boom and bust cycle continued in the 1980s with the onset of another recession. This downturn caused another crisis among US farmers, with interest rates rising as high as 21% in some cases. Many farms with high borrowings were lost to the banks.

“Around 1985/86 was when things went bad. People got into trouble. Banks got into trouble. In this area alone, 5% to 10% of farmers went out of business, with many more having a really tough time.” In 1962, total farm debt in the US was $60bn, but by 1983 farm debt had skyrocketed to $216bn.

Tight money policies by the Federal Reserve (introduced to bring down high interest rates) cut back on government support to agriculture and caused the value of farmland to drop. In 1985, country singer Willie Nelson organised the first of the Farm Aid concerts to benefit indebted farmers.

At this time, grain prices were low, with corn and soya bean prices back to $1.30 /bushel (€42/t) and $5.26/bushel (€161/t) respectively. Despite this, Larry continued to expand their farm operation in partnership with his sons.

The 1990s marked a big change in farm technology with the adoption of genetically modified (GM) corn and soya beans at farm level. Larry explained that farmers were willing to try anything if they thought there was money in it.

“If farmers could make money at it, they were willing to try it. It was slow at the start and some were against it, but eventually the majority went to it.”

2000 onwards

GM technology brought wonders to US farmers and, according to Larry, it changed the course of agriculture significantly. The farming landscape continued to follow the trend observed over the past number of decades, with farm numbers decreasing to 2,060,000 and average size increasing, now at 461 acres.

The farm now produces commodity and food-grade corn and commodity and seed beans, much of which is GM. The decision to stop producing livestock and switch solely to grain production was replicated in the surrounding area, Larry states.

“In the past, half of the land around us for probably 10km would have been pasture. Now it is more like 10%. There are probably only 10 to 15 people with hogs and only two left in dairying in our county.”

From 2000 onwards, precision farming technology really took off and farmers adopted technologies such as auto steer, section control, yield monitoring, variable rate fertiliser application and much more.

Larry, his sons and grandsons continued the campaign of increasing farm size and now cover 5,000 acres between the three generations.

Lesson learned

Larry acknowledges that there were many challenges in the past, but overall he’s been very fortunate to have lived during this period. His attitude remains the same; if challenges arise, just work through them.

“Things come up and you just work through them and keep going. We’ve been very fortunate to live through the period that we have. On the whole, it’s been good times.”

When it comes to the future, he urged people not to be too resistant to change. Similar to when GM crops were first grown in his area, some farmers were hesitant to grow them. However, once they saw that it made economic sense, the majority grew them.

“Don’t be too resistant to change. Figure it out. If it’s economical, then go and do it.”

SHARING OPTIONS: