Irish Grass Fed Beef, complete with its PGI, has started its journey onto the supermarket shelves in Italy. It was another positive photo opportunity for the minister, and Bord Bia will be the engine behind a comprehensive promotion campaign. However, it will be Italian consumers in the first instance, with hopefully more to follow across Europe soon, that will determine the level of success the PGI brand achieves. With this positive vibe, what’s not to like about labelling beef and, indeed, other Irish agri food products?

Downside

When as dependent on export markets as the Irish agrifood sector is, the threat from labelling has the potential to far outweigh the benefit, particularly when it comes to country-of-origin labelling (COOL). This differs from PGI, in that it is a legislative requirement for meat in the EU, having been introduced for just beef originally over 20 years ago to give consumers confidence in the aftermath of the BSE issue. Whereas everything about a PGI is voluntary and has to be earned, COOL labelling merely identifies where an animal was born, raised and processed.

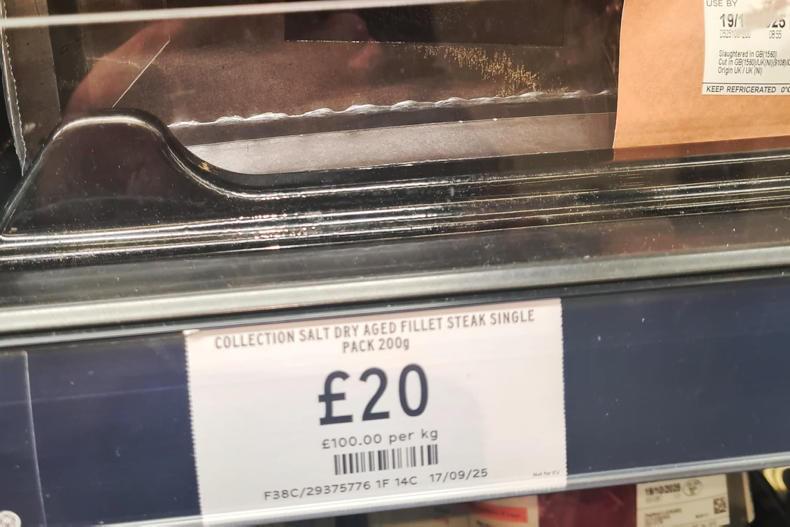

This is no big deal where a country more or less consumes as much as it produces. Then for a country that produces less, it creates a premium for domestically produced product, as is the case in the UK. This is at least part of the reason why UK cattle prices are consistently ahead of Irish farmgate prices.

Just as Irish consumers, in the main, have a preference for Irish product over imported product, the same applies to markets that Ireland exports to, so bold labelling works to our disadvantage.

North American issue

COOL labelling has resurfaced as an issue in North America over recent weeks as well.

There has been a long-running dispute between the US, Canada and Mexico stretching back over two decades, about US beef labelling disadvantaging its neighbours.

From 2026, beef will have to be born, reared and processed in US to carry Product of US label, which is voluntary.

The US legislation was similar to that in the EU, in that it required the on-pack label at retailers to show where the animal was born, where it was reared and where it was processed.

An action was successfully brought to the Wold Trade Organization for adjudication and it was in favour of Canada and Mexico, ruling that the label was anti-competitive by differentiating US beef fromimported.

The issue has been dormant since 2016, when the US legislated to repeal the COOL requirements for beef, but an amendment to the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 was brought forward last year.

Last week, Secretary Vilsack announced new rules for a voluntary Product of USA label that would be applicable from 1 January 2026. If a product carries this label, it has to show that it was born, reared and processed in the US.

New development

This has not been welcomed in Canada and this week the Canadian Cattle Associations newsletter recorded its objection to changes. It highlighted that Canadian cattle would no longer be able to cross the border for feeding and processing and carry a US label.

It pointed out that systems have been harmonised either side of the US-Canada border and that with the US accounting for 70% of their export cattle trade, the move will hit producers and consumers on both sides of the border.

The two-decade wrangle between the US and Canada looks like it will continue until 2026 at least.

Settled position in Europe for now

The horsemeat scandal of 2013 led to reopening of the labelling debate and in 2016 the EU Commission agreed to France testing labels for the origin of milk and meat in processed foods. However, in 2021, French courts ruled that it wasn’t mandatory to indicate the origin of milk on product labels.

That meant a settled position in Europe on compulsory labelling and farmers either side of the border on the island of Ireland will be best served if it remains so.

Northern processors have adapted to developing export markets for cattle coming from south of the border which cannot be classified as either British or Irish.

Where branding is promoting unique characteristics and is voluntary, as is the case with PGI, it has potential to add value to Irish agri food produce.

However, where it is compulsory and refers to only the country of origin, Irish agri food has more to lose than gain, given our position in export markets.

Irish Grass Fed Beef, complete with its PGI, has started its journey onto the supermarket shelves in Italy. It was another positive photo opportunity for the minister, and Bord Bia will be the engine behind a comprehensive promotion campaign. However, it will be Italian consumers in the first instance, with hopefully more to follow across Europe soon, that will determine the level of success the PGI brand achieves. With this positive vibe, what’s not to like about labelling beef and, indeed, other Irish agri food products?

Downside

When as dependent on export markets as the Irish agrifood sector is, the threat from labelling has the potential to far outweigh the benefit, particularly when it comes to country-of-origin labelling (COOL). This differs from PGI, in that it is a legislative requirement for meat in the EU, having been introduced for just beef originally over 20 years ago to give consumers confidence in the aftermath of the BSE issue. Whereas everything about a PGI is voluntary and has to be earned, COOL labelling merely identifies where an animal was born, raised and processed.

This is no big deal where a country more or less consumes as much as it produces. Then for a country that produces less, it creates a premium for domestically produced product, as is the case in the UK. This is at least part of the reason why UK cattle prices are consistently ahead of Irish farmgate prices.

Just as Irish consumers, in the main, have a preference for Irish product over imported product, the same applies to markets that Ireland exports to, so bold labelling works to our disadvantage.

North American issue

COOL labelling has resurfaced as an issue in North America over recent weeks as well.

There has been a long-running dispute between the US, Canada and Mexico stretching back over two decades, about US beef labelling disadvantaging its neighbours.

From 2026, beef will have to be born, reared and processed in US to carry Product of US label, which is voluntary.

The US legislation was similar to that in the EU, in that it required the on-pack label at retailers to show where the animal was born, where it was reared and where it was processed.

An action was successfully brought to the Wold Trade Organization for adjudication and it was in favour of Canada and Mexico, ruling that the label was anti-competitive by differentiating US beef fromimported.

The issue has been dormant since 2016, when the US legislated to repeal the COOL requirements for beef, but an amendment to the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 was brought forward last year.

Last week, Secretary Vilsack announced new rules for a voluntary Product of USA label that would be applicable from 1 January 2026. If a product carries this label, it has to show that it was born, reared and processed in the US.

New development

This has not been welcomed in Canada and this week the Canadian Cattle Associations newsletter recorded its objection to changes. It highlighted that Canadian cattle would no longer be able to cross the border for feeding and processing and carry a US label.

It pointed out that systems have been harmonised either side of the US-Canada border and that with the US accounting for 70% of their export cattle trade, the move will hit producers and consumers on both sides of the border.

The two-decade wrangle between the US and Canada looks like it will continue until 2026 at least.

Settled position in Europe for now

The horsemeat scandal of 2013 led to reopening of the labelling debate and in 2016 the EU Commission agreed to France testing labels for the origin of milk and meat in processed foods. However, in 2021, French courts ruled that it wasn’t mandatory to indicate the origin of milk on product labels.

That meant a settled position in Europe on compulsory labelling and farmers either side of the border on the island of Ireland will be best served if it remains so.

Northern processors have adapted to developing export markets for cattle coming from south of the border which cannot be classified as either British or Irish.

Where branding is promoting unique characteristics and is voluntary, as is the case with PGI, it has potential to add value to Irish agri food produce.

However, where it is compulsory and refers to only the country of origin, Irish agri food has more to lose than gain, given our position in export markets.

SHARING OPTIONS