This time of year can see grass growth drop rapidly. As a result, many livestock farmers look to supplementary feeding of cattle in fields.

Grass growth has tailed off through September. Aberdeenshire farmers measuring grass growth in the GrassCheckGB programme recorded growth of 15kgDM/day at 15% dry matter.

Andrew is happy how his fodder beet is progressing. This picture was taken at the start of the month. The plan is to put the dry cows onto the beet in November. Then lift some to supplement diets once the cows are housed and for the growing cattle.

To ensure cattle energy requirements are met, Andrew Biffen has started feeding treated straw to cattle in the fields. Andrew’s treated straw is costing around £19.50/bale to feed.

Staggers risk

As the grazing season winds downs across the country, farmers need to be watchful of staggers or grass tetany risk. Cows will be eating high volumes of low-fibre grass, rapidly passing though the gut and increasing the likelihood of staggers. The chances of cattle getting the disease will also rise at weaning time. Cows are even more susceptible when stressed.

The condition is caused by a deficiency of magnesium (Mg) in the blood. This is a rapidly fatal condition in beef and dairy cows (and occasionally calves) and a common cause of sudden death, ie an animal found dead in the field without any history of disease or ill-health in the previous days.

While the cow does have storage of magnesium in the skeleton, this is not readily available when needed for rapid release to the bloodstream. Therefore, the cow must ingest sufficient magnesium on a daily basis to prevent deficiency and subsequent disease.

The level of Mg obtained from forage is depressed by factors such as:

Heavy nitrogen fertilisation. Rapidly growing swards. High potassium in the soil. Lush, low-fibre grass and high nitrogen, which result in a rapid passage through the gut and an increased ruminal pH, both of which further decrease magnesium absorption. Low dietary sodium, which is needed for Mg absorption from the intestine.Grass tetany is also very much a disease associated with stress. The common stressors for both beef and dairy cows include:Cows in heat (not eating a lot that day and exerting a lot of energy rising on other animals, etc).Bad weather conditions.Changes in diet and pasture.Transport.Concurrent disease that may affect feed intake.Symptoms

Magnesium in the body acts as an electrical suppressant of nerve and muscle activity.

Therefore, deficiency will lead to excitability. In the early stages, the cow will appear nervous, with a stiff-legged walk and often a high head carriage and a wide-eyed stare.

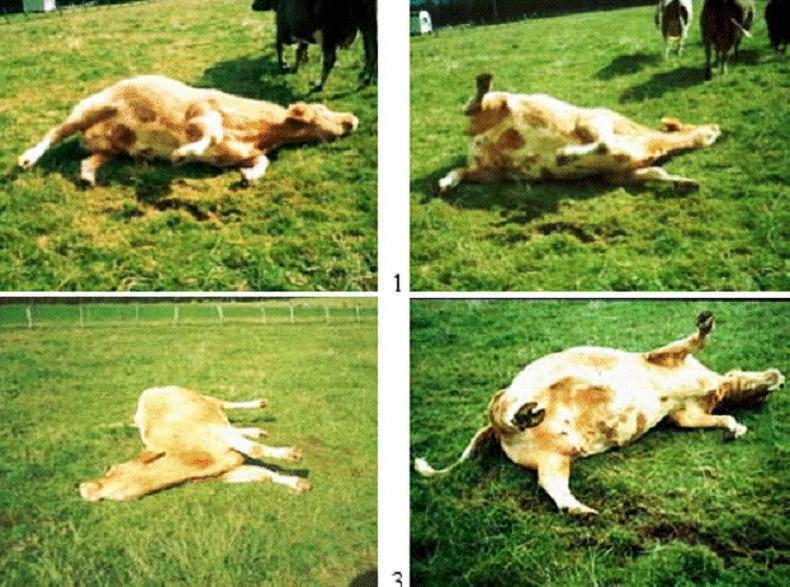

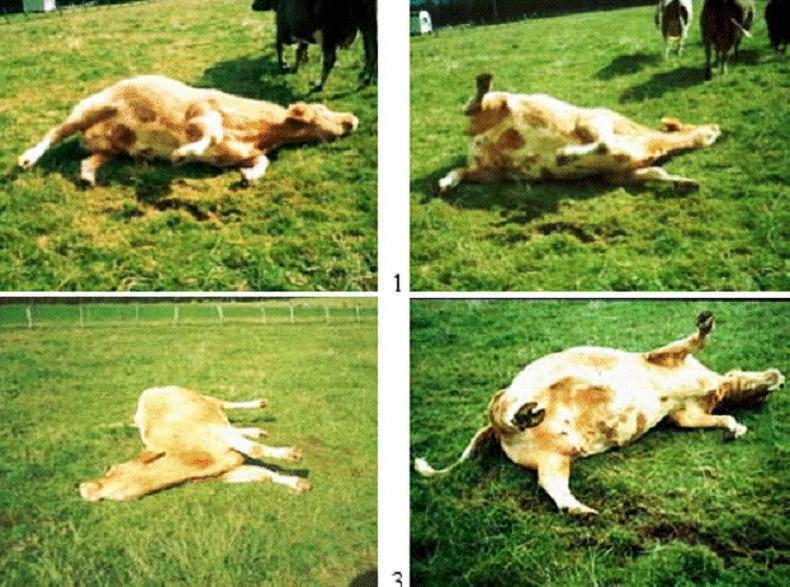

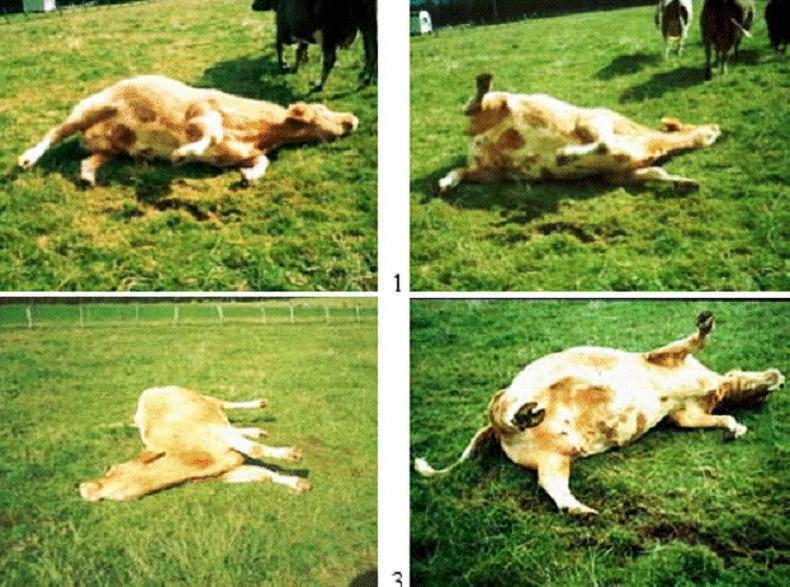

Muscle tremors will become apparent and, if suddenly excited, the cow may fall over and go into hypomagnesaemic tetany shock.

This is essentially a state of uncontrolled seizure (see Figure 1) – the cow’s legs will be either stiff or in spasm, or they will be paddling violently.

Figure 1.

Her head will tend to arch backwards in severe spasm, and her eyelids will flutter with a loud “click” when approached with a hand.

Frothing from the mouth and chomping of the jaws are common. Some cows will be found dead with the ground torn up around them, underlying the fact that grass tetany is a true emergency and is fatal in a very short time.

Treatment

Grass tetany warrants veterinary attention as soon as possible. Treatment depends on the severity of clinical signs. If the cow is convulsing or seizuring, then initial sedation is of primary importance to prevent brain damage. Following this, the vet will administer a mixture of calcium and magnesium intravenously, followed by 400ml of magnesium sulphate solution subcutaneously (under the skin). It is very important that this concentrated magnesium sulphate is not given intravenously, as it is likely to cause cardiac arrest and death.

They have ensured all cows have access to high mag tubs and fodder to reduce the risk of staggers this back end.

Following the administration of magnesium and sedatives, the excitability should reduce quite quickly. The cow should be placed sitting up.

If the cow did not need to be sedated, it is likely that she will be able to stand within an hour. However, if heavy sedation was required, the cow might not rise for several hours.

When assessing the progress of the cow, attention should be paid to the symmetry of the head. If the eyes are pointing in the wrong direction, or there is an ear down, for example, it is likely that brain damage has occurred, with a resulting hopeless prognosis.

Control/prevention

Most of our farmers are using high-magnesium mineral licks to prevent staggers. However, Andy Duffus, who runs the extensive farm at Tomintoul, doesn’t have the build-up of potassium in the soil which has reduced his risk.

Options for increasing magnesium intake include:

Giving free access to high Mg minerals, either by way of powder mineral or mineral licks. Feeding high Mg cobs (calves also eating the cobs are prone to scour).Buffer-feeding with hay or straw prior to going out onto lush pasture prevents significant drops in ruminal pH and helps prevent hypomagnesaemia by reducing the rate of passage of food through the gastrointestinal tract, allowing more time for magnesium absorption.Increasing the clover content of the sward.Avoiding the grazing of cows on pastures that have had heavy slurry applications or the application of high-potassium fertilisers. Regular liming of grazing land to maintain the correct soil pH and improve Mg uptake.Pasture dusting with calcined magnesite can be carried out every second or third day.The addition of Mg to the drinking water.The use of magnesium bullets – at least two bullets/boluses should be used per cow, which will release Mg at a controlled rate each day for four to six weeks.

This time of year can see grass growth drop rapidly. As a result, many livestock farmers look to supplementary feeding of cattle in fields.

Grass growth has tailed off through September. Aberdeenshire farmers measuring grass growth in the GrassCheckGB programme recorded growth of 15kgDM/day at 15% dry matter.

Andrew is happy how his fodder beet is progressing. This picture was taken at the start of the month. The plan is to put the dry cows onto the beet in November. Then lift some to supplement diets once the cows are housed and for the growing cattle.

To ensure cattle energy requirements are met, Andrew Biffen has started feeding treated straw to cattle in the fields. Andrew’s treated straw is costing around £19.50/bale to feed.

Staggers risk

As the grazing season winds downs across the country, farmers need to be watchful of staggers or grass tetany risk. Cows will be eating high volumes of low-fibre grass, rapidly passing though the gut and increasing the likelihood of staggers. The chances of cattle getting the disease will also rise at weaning time. Cows are even more susceptible when stressed.

The condition is caused by a deficiency of magnesium (Mg) in the blood. This is a rapidly fatal condition in beef and dairy cows (and occasionally calves) and a common cause of sudden death, ie an animal found dead in the field without any history of disease or ill-health in the previous days.

While the cow does have storage of magnesium in the skeleton, this is not readily available when needed for rapid release to the bloodstream. Therefore, the cow must ingest sufficient magnesium on a daily basis to prevent deficiency and subsequent disease.

The level of Mg obtained from forage is depressed by factors such as:

Heavy nitrogen fertilisation. Rapidly growing swards. High potassium in the soil. Lush, low-fibre grass and high nitrogen, which result in a rapid passage through the gut and an increased ruminal pH, both of which further decrease magnesium absorption. Low dietary sodium, which is needed for Mg absorption from the intestine.Grass tetany is also very much a disease associated with stress. The common stressors for both beef and dairy cows include:Cows in heat (not eating a lot that day and exerting a lot of energy rising on other animals, etc).Bad weather conditions.Changes in diet and pasture.Transport.Concurrent disease that may affect feed intake.Symptoms

Magnesium in the body acts as an electrical suppressant of nerve and muscle activity.

Therefore, deficiency will lead to excitability. In the early stages, the cow will appear nervous, with a stiff-legged walk and often a high head carriage and a wide-eyed stare.

Muscle tremors will become apparent and, if suddenly excited, the cow may fall over and go into hypomagnesaemic tetany shock.

This is essentially a state of uncontrolled seizure (see Figure 1) – the cow’s legs will be either stiff or in spasm, or they will be paddling violently.

Figure 1.

Her head will tend to arch backwards in severe spasm, and her eyelids will flutter with a loud “click” when approached with a hand.

Frothing from the mouth and chomping of the jaws are common. Some cows will be found dead with the ground torn up around them, underlying the fact that grass tetany is a true emergency and is fatal in a very short time.

Treatment

Grass tetany warrants veterinary attention as soon as possible. Treatment depends on the severity of clinical signs. If the cow is convulsing or seizuring, then initial sedation is of primary importance to prevent brain damage. Following this, the vet will administer a mixture of calcium and magnesium intravenously, followed by 400ml of magnesium sulphate solution subcutaneously (under the skin). It is very important that this concentrated magnesium sulphate is not given intravenously, as it is likely to cause cardiac arrest and death.

They have ensured all cows have access to high mag tubs and fodder to reduce the risk of staggers this back end.

Following the administration of magnesium and sedatives, the excitability should reduce quite quickly. The cow should be placed sitting up.

If the cow did not need to be sedated, it is likely that she will be able to stand within an hour. However, if heavy sedation was required, the cow might not rise for several hours.

When assessing the progress of the cow, attention should be paid to the symmetry of the head. If the eyes are pointing in the wrong direction, or there is an ear down, for example, it is likely that brain damage has occurred, with a resulting hopeless prognosis.

Control/prevention

Most of our farmers are using high-magnesium mineral licks to prevent staggers. However, Andy Duffus, who runs the extensive farm at Tomintoul, doesn’t have the build-up of potassium in the soil which has reduced his risk.

Options for increasing magnesium intake include:

Giving free access to high Mg minerals, either by way of powder mineral or mineral licks. Feeding high Mg cobs (calves also eating the cobs are prone to scour).Buffer-feeding with hay or straw prior to going out onto lush pasture prevents significant drops in ruminal pH and helps prevent hypomagnesaemia by reducing the rate of passage of food through the gastrointestinal tract, allowing more time for magnesium absorption.Increasing the clover content of the sward.Avoiding the grazing of cows on pastures that have had heavy slurry applications or the application of high-potassium fertilisers. Regular liming of grazing land to maintain the correct soil pH and improve Mg uptake.Pasture dusting with calcined magnesite can be carried out every second or third day.The addition of Mg to the drinking water.The use of magnesium bullets – at least two bullets/boluses should be used per cow, which will release Mg at a controlled rate each day for four to six weeks.

SHARING OPTIONS