As readers will know, Ireland’s anaerobic digestion (AD) industry has been painfully slow to get off the ground.

However, it is generally accepted that we will see the industry finally take flight over the coming decade as there are few technologies as well suited to help meet our renewable heat and transport targets along with reducing agriculture’s emissions profile.

It is expected that the average farm-based AD plant in Ireland will be relatively large.

This is in order to help achieve economies of scale, particularly when it comes to gas purification and compression.

Most AD biogas produced in Ireland over the coming decade will be upgraded to biomethane and used for either heat generation or in the transport sector. These sectors are difficult to decarbonise as, in many cases, they can’t be electrified with today’s technology.

This scale will be beyond the reach of many farmers, so co-operative-style structures are likely to develop

To put this in context, the average farm-based AD plant in Northern Ireland has an electrical output of around 500kW (kilowatt). The average farm-based plant in Ireland will be at least twice the size of that, or one megawatt in equivalent electrical output.

This scale will be beyond the reach of many farmers, so co-operative-style structures are likely to develop. Make no mistake, this scale of plant and level of industry ambition will be required in order to make up for lost ground and help meet our renewable heat and transport targets.

A case for small-scale

A common question I get asked in conversation with farmers about AD is why it is not feasible to develop a considerably smaller AD plant (sub 500kW) in order to satisfy their own electricity and heat requirements and export the remainder of the electricity to the grid?

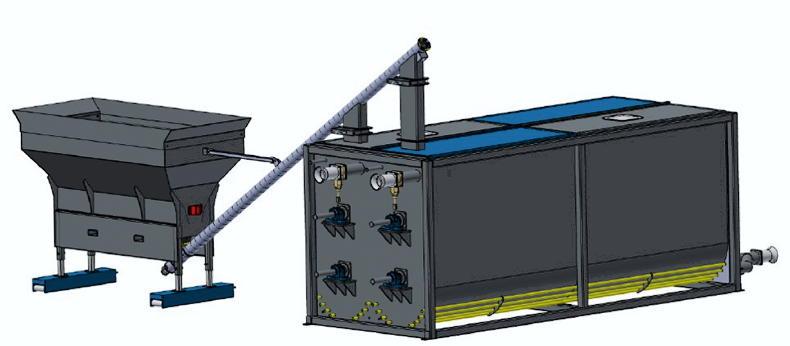

The design of the demonstration-scale system.

The answer mostly came down to economics and a lack of support for the sector.

Good work is already ongoing in this area

However, times are changing and so too are the economics of such a proposal.Biogas fuelled micro-scale combine heat and power plants are expected to be supported under the Micro-Generation Scheme up to 30kW in output, while biogas-fuelled boilers are supported under the Support Scheme for Renewable Heat.

Good work is already ongoing in this area by the Irish Bioenergy Association’s EIP Small Biogas Demonstration Project. We will have more on developments with this later in the year.

However, another piece of research in this area by Seán O’Connor of IT Sligo was recently brought to national attention. Sean claimed the prestigious Postgraduate Researcher of the Year Award 2020 from the Environmental Science Association of Ireland on his work into the development of small-scale anaerobic digestion (SSAD).

SSAD describes plants which produce electricity via combined heat and power plant with an electrical capacity ranging from 15kW to 100kW.

SSAD provides a number of benefits over larger plants because of the technology’s flexibility in terms of feedstock requirements.

Sean’s research found that small-scale plants not only provide the benefits of on-site energy generation, a nutrient-rich organic fertiliser, a reduction in pathogenic loads and reductions in odour and greenhouse gas emissions, but also provide economic benefits for smaller farms.

One of Sean’s published studies assessed the viability of SSAD in Ireland by modelling the technical, economic, and environmental considerations of operating such plants on commercial Irish dairy farms.

The study examined the integration of SSAD on dairy farms with various herd sizes ranging from 50 to 250 dairy cows, feeding the digester with slurry and grass.

He found that, on average, the volume of feedstock available on-farm was sufficient to generate enough electricity to meet the farm’s energy needs, with surplus energy exported.

The study found SSAD systems to be economically feasible and profitable within the plant’s lifespan on farms with dairy herd sizes greater than 100 cows, with payback periods of eight to 13 years.

This factored in the displacement of imported electricity, the sale of excess electricity to the grid, the sale of renewable heat (supported under the Support Scheme for Renewable Heat) and displacing chemical fertiliser with digestate.

All scenarios which he explored showed a net CO2 reduction ranging between 2,059kg and 173,237kg CO2-eq per year. The insights from this study show that SSAD is an economically sustainable method for the mitigation of GHG emissions in the Irish agriculture sector.

This research has been carried out under the EU INTERREG-funded Renewable Engine project with collaboration from an industry partner, Organic Power.

Seán has been working with Organic Power to develop and test a modular SSAD plant, with the goal of reducing the relatively high fixed costs associated with traditional AD plants.

The system under development has a plug-and-play design, capable of operating inside two standard transport containers.

This demonstration-scale system is currently under testing at the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI), Hillsborough, Northern Ireland.

As readers will know, Ireland’s anaerobic digestion (AD) industry has been painfully slow to get off the ground.

However, it is generally accepted that we will see the industry finally take flight over the coming decade as there are few technologies as well suited to help meet our renewable heat and transport targets along with reducing agriculture’s emissions profile.

It is expected that the average farm-based AD plant in Ireland will be relatively large.

This is in order to help achieve economies of scale, particularly when it comes to gas purification and compression.

Most AD biogas produced in Ireland over the coming decade will be upgraded to biomethane and used for either heat generation or in the transport sector. These sectors are difficult to decarbonise as, in many cases, they can’t be electrified with today’s technology.

This scale will be beyond the reach of many farmers, so co-operative-style structures are likely to develop

To put this in context, the average farm-based AD plant in Northern Ireland has an electrical output of around 500kW (kilowatt). The average farm-based plant in Ireland will be at least twice the size of that, or one megawatt in equivalent electrical output.

This scale will be beyond the reach of many farmers, so co-operative-style structures are likely to develop. Make no mistake, this scale of plant and level of industry ambition will be required in order to make up for lost ground and help meet our renewable heat and transport targets.

A case for small-scale

A common question I get asked in conversation with farmers about AD is why it is not feasible to develop a considerably smaller AD plant (sub 500kW) in order to satisfy their own electricity and heat requirements and export the remainder of the electricity to the grid?

The design of the demonstration-scale system.

The answer mostly came down to economics and a lack of support for the sector.

Good work is already ongoing in this area

However, times are changing and so too are the economics of such a proposal.Biogas fuelled micro-scale combine heat and power plants are expected to be supported under the Micro-Generation Scheme up to 30kW in output, while biogas-fuelled boilers are supported under the Support Scheme for Renewable Heat.

Good work is already ongoing in this area by the Irish Bioenergy Association’s EIP Small Biogas Demonstration Project. We will have more on developments with this later in the year.

However, another piece of research in this area by Seán O’Connor of IT Sligo was recently brought to national attention. Sean claimed the prestigious Postgraduate Researcher of the Year Award 2020 from the Environmental Science Association of Ireland on his work into the development of small-scale anaerobic digestion (SSAD).

SSAD describes plants which produce electricity via combined heat and power plant with an electrical capacity ranging from 15kW to 100kW.

SSAD provides a number of benefits over larger plants because of the technology’s flexibility in terms of feedstock requirements.

Sean’s research found that small-scale plants not only provide the benefits of on-site energy generation, a nutrient-rich organic fertiliser, a reduction in pathogenic loads and reductions in odour and greenhouse gas emissions, but also provide economic benefits for smaller farms.

One of Sean’s published studies assessed the viability of SSAD in Ireland by modelling the technical, economic, and environmental considerations of operating such plants on commercial Irish dairy farms.

The study examined the integration of SSAD on dairy farms with various herd sizes ranging from 50 to 250 dairy cows, feeding the digester with slurry and grass.

He found that, on average, the volume of feedstock available on-farm was sufficient to generate enough electricity to meet the farm’s energy needs, with surplus energy exported.

The study found SSAD systems to be economically feasible and profitable within the plant’s lifespan on farms with dairy herd sizes greater than 100 cows, with payback periods of eight to 13 years.

This factored in the displacement of imported electricity, the sale of excess electricity to the grid, the sale of renewable heat (supported under the Support Scheme for Renewable Heat) and displacing chemical fertiliser with digestate.

All scenarios which he explored showed a net CO2 reduction ranging between 2,059kg and 173,237kg CO2-eq per year. The insights from this study show that SSAD is an economically sustainable method for the mitigation of GHG emissions in the Irish agriculture sector.

This research has been carried out under the EU INTERREG-funded Renewable Engine project with collaboration from an industry partner, Organic Power.

Seán has been working with Organic Power to develop and test a modular SSAD plant, with the goal of reducing the relatively high fixed costs associated with traditional AD plants.

The system under development has a plug-and-play design, capable of operating inside two standard transport containers.

This demonstration-scale system is currently under testing at the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI), Hillsborough, Northern Ireland.

SHARING OPTIONS