Save them, says the Citizen, the giant ash of Galway and the chieftain elm of Kildare with a fortyfoot bole and an acre of foliage.

– From Ulysses by James Joyce

The fictional Citizen who appears in the “Cyclops” episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses had many faults but his plea to save the ash and elm species was both heartfelt and prescient. Joyce’s favoured sport was cricket, although hurling is mentioned briefly in the novel. Ironically, the Citizen is based on Michael Cusack, co-founder of the GAA.

Dutch elm disease, which reached Ireland in the 1960s, virtually wiped out most of the native wych and introduced English elms while ash dieback has destroyed ash woodlands, plantations and hedgerow trees throughout Ireland since it arrived here 10 years ago.

The loss of ash is incalculable in a commercial, heritage, social and sporting context. Just like elm, isolated resistant trees will remain to remind us of what is lost and what may be restored if our researchers can develop a new generation of ash trees that resist dieback.

Research continues in Teagasc to identify disease-resistant ash trees and build up a gene bank to eventually produce disease-tolerant ash.

In the meantime, hurley and ash specialist furniture makers are looking for alternative species and alternative ways of making hurleys. Furniture manufacturers have a wide range of hardwood options but the choice is limited for hurley makers. For decades, they have been importing ash planks but ash dieback combined with the destructive emerald ash borer beetle is likely to eventually wipe out most ash in Europe and the US in the coming years.

So, the search is on for an alternative species to ash. The Torpeys in Sixmilebridge in Co Clare have taken the lead and developed their Bambú hurley range. Manufactured from engineered fast-growing bamboo, this hurley brand is being used by club and intercounty players since it was launched in 2020.

Engineered wood requires specialist technology which is outside the scope of hurley makers. “Hurley making is the last of the true cottage industries, with up to 350 people employed in the sector including harvesting, planking and making the hurleys,” says Mick Power of Coillte and a member of the Ash Society of Ireland (ASI).

When I met Albert Nevin of Nevin Hurleys and Michael Somers, forestry development officer with Teagasc, ash supply and alternative species were the main topics. Nevin is a third-generation hurley maker based in Clononey, Shannon Harbour, Co Offaly, and highly regarded in the trade. Chair of the Irish Guild of Ash Hurley Makers, like Power and Somers, he is a member of ASI.

Looking around his workshop gives an indication of the evolution of hurling. The shape of the hurley has changed over the years while accessories – which he also supplies – such as helmets, telescopic training poles, field cones and training bibs have only been in common use for little more than a decade. He also promotes hurley reuse and supplies a repair service for hurlers and camogie players who place strong emphasis on the longevity of a good hurley.

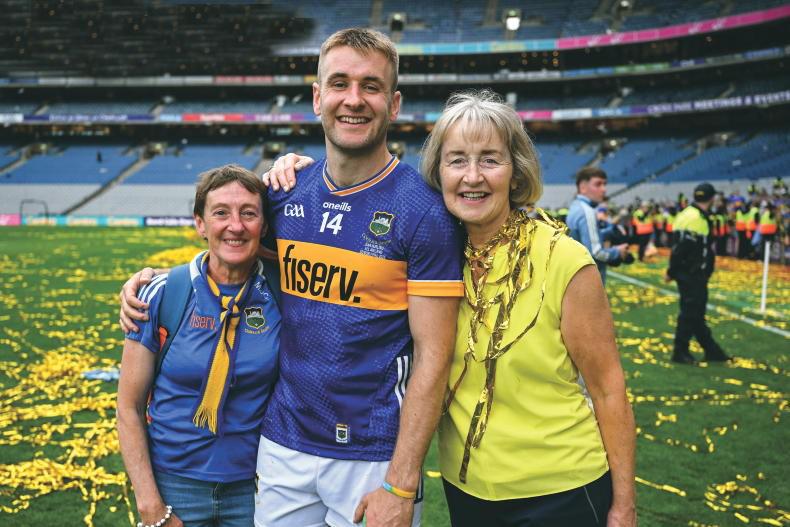

Although supply is limited, Albert Nevin (right) is still able to source sufficient hurley ash but believes, like Michael Sommers, that research is necessary to find an alternative species and an alternative way of making hurleys. \Donal Magner

He explains how the sport itself has evolved to a more skilful possession-based game. As a result the number of broken hurleys has decreased “but the demand continues as more and more people are playing the game”, he says.

But the biggest change of all is on the way, as ash is likely to become redundant. “I can still source sufficient supply but it’s getting scarce both in Ireland and the continent, especially since the war in Ukraine,” says Nevin. It is difficult to assess availability as there isn’t a site-specific database or inventory of ash sources, he explains. “We depend on word of mouth,” he adds, saying he sources ash “throughout the country” just as his customers are also nationwide.

He has experimented with laminates which would have advantages in making more hurleys available from different sections of the tree.

He recently experimented by making a hurley from maple which his daughter Emma uses and so far it is displaying many of the characteristics of ash.

“Just because ash has been the traditional species, doesn’t mean it’s the only species for hurley making,” says Somers. “Ash was readily available as hedgerow and woodland trees in the past but we now have to look at other species,” he maintains. “We need to look at research into laminates and engineering wood.”

Power says that the ASI work involves a multipurpose approach including manufacturing in the short term and developing a resistant strain in the long term.

In the meantime, Nevin and other hurley makers have limited time on their side as they exploit diminishing supplies of ash in Ireland and the continent and possibly further afield.

But time is running out.

Alternative

hardwood species

The demise of ash has thrown Ireland’s dearth of native and naturalised broadleaf species into sharp focus not just for hurley making but furniture, flooring and other hardwood added-value specialist uses.

Close to 30% of annual afforestation programmes since 2000 comprised broadleaf – mainly native – species but ash provided the bulk of planting up until 2012. Most of these plantations are now being written off so attention turns to alternative native and naturalised species.

Oak, cherry, sycamore, beech, sweet chestnut, maple, alder and birch have been identified as alternative species for a wide range of furniture and other uses but possibly two – maple and sycamore – are close to ash in terms of flexibility and density. To dispel doubts about the quality and yield of some species such as alder and birch, the results of Teagasc tree improvement programmes which began in 2012 are showing positive results.

Michael Sommers inspects downy birch research plot in the townland of Coolbaun, Co Tipperary, planted in 1998. \Donal Magner

Somers is proud of the performance of a downy birch (Betula pubescens) research plot in the townland of Coolbaun, Co Tipperary, a short distance from the shore of Lough Derg. It is showing remarkable vigour and form. Planted in 1998, from 27 Irish provenances, this plot should provide commercial furniture lengths after two more thinnings. A nearby silver birch (B. pendula) trial of native and some German and French provenances is also promising.

Birch and alder tree improvement programmes demonstrate that commercial timber production is achievable over short rotations just like ash. Eventually an ash disease-resistant strain will also be achieved. “When that happens, the lesson learned is that ash will never be planted pure again,” says Power. “It is a species that works well in mixtures with other broadleaves and conifers, especially Norway spruce.”

Save them, says the Citizen, the giant ash of Galway and the chieftain elm of Kildare with a fortyfoot bole and an acre of foliage.

– From Ulysses by James Joyce

The fictional Citizen who appears in the “Cyclops” episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses had many faults but his plea to save the ash and elm species was both heartfelt and prescient. Joyce’s favoured sport was cricket, although hurling is mentioned briefly in the novel. Ironically, the Citizen is based on Michael Cusack, co-founder of the GAA.

Dutch elm disease, which reached Ireland in the 1960s, virtually wiped out most of the native wych and introduced English elms while ash dieback has destroyed ash woodlands, plantations and hedgerow trees throughout Ireland since it arrived here 10 years ago.

The loss of ash is incalculable in a commercial, heritage, social and sporting context. Just like elm, isolated resistant trees will remain to remind us of what is lost and what may be restored if our researchers can develop a new generation of ash trees that resist dieback.

Research continues in Teagasc to identify disease-resistant ash trees and build up a gene bank to eventually produce disease-tolerant ash.

In the meantime, hurley and ash specialist furniture makers are looking for alternative species and alternative ways of making hurleys. Furniture manufacturers have a wide range of hardwood options but the choice is limited for hurley makers. For decades, they have been importing ash planks but ash dieback combined with the destructive emerald ash borer beetle is likely to eventually wipe out most ash in Europe and the US in the coming years.

So, the search is on for an alternative species to ash. The Torpeys in Sixmilebridge in Co Clare have taken the lead and developed their Bambú hurley range. Manufactured from engineered fast-growing bamboo, this hurley brand is being used by club and intercounty players since it was launched in 2020.

Engineered wood requires specialist technology which is outside the scope of hurley makers. “Hurley making is the last of the true cottage industries, with up to 350 people employed in the sector including harvesting, planking and making the hurleys,” says Mick Power of Coillte and a member of the Ash Society of Ireland (ASI).

When I met Albert Nevin of Nevin Hurleys and Michael Somers, forestry development officer with Teagasc, ash supply and alternative species were the main topics. Nevin is a third-generation hurley maker based in Clononey, Shannon Harbour, Co Offaly, and highly regarded in the trade. Chair of the Irish Guild of Ash Hurley Makers, like Power and Somers, he is a member of ASI.

Looking around his workshop gives an indication of the evolution of hurling. The shape of the hurley has changed over the years while accessories – which he also supplies – such as helmets, telescopic training poles, field cones and training bibs have only been in common use for little more than a decade. He also promotes hurley reuse and supplies a repair service for hurlers and camogie players who place strong emphasis on the longevity of a good hurley.

Although supply is limited, Albert Nevin (right) is still able to source sufficient hurley ash but believes, like Michael Sommers, that research is necessary to find an alternative species and an alternative way of making hurleys. \Donal Magner

He explains how the sport itself has evolved to a more skilful possession-based game. As a result the number of broken hurleys has decreased “but the demand continues as more and more people are playing the game”, he says.

But the biggest change of all is on the way, as ash is likely to become redundant. “I can still source sufficient supply but it’s getting scarce both in Ireland and the continent, especially since the war in Ukraine,” says Nevin. It is difficult to assess availability as there isn’t a site-specific database or inventory of ash sources, he explains. “We depend on word of mouth,” he adds, saying he sources ash “throughout the country” just as his customers are also nationwide.

He has experimented with laminates which would have advantages in making more hurleys available from different sections of the tree.

He recently experimented by making a hurley from maple which his daughter Emma uses and so far it is displaying many of the characteristics of ash.

“Just because ash has been the traditional species, doesn’t mean it’s the only species for hurley making,” says Somers. “Ash was readily available as hedgerow and woodland trees in the past but we now have to look at other species,” he maintains. “We need to look at research into laminates and engineering wood.”

Power says that the ASI work involves a multipurpose approach including manufacturing in the short term and developing a resistant strain in the long term.

In the meantime, Nevin and other hurley makers have limited time on their side as they exploit diminishing supplies of ash in Ireland and the continent and possibly further afield.

But time is running out.

Alternative

hardwood species

The demise of ash has thrown Ireland’s dearth of native and naturalised broadleaf species into sharp focus not just for hurley making but furniture, flooring and other hardwood added-value specialist uses.

Close to 30% of annual afforestation programmes since 2000 comprised broadleaf – mainly native – species but ash provided the bulk of planting up until 2012. Most of these plantations are now being written off so attention turns to alternative native and naturalised species.

Oak, cherry, sycamore, beech, sweet chestnut, maple, alder and birch have been identified as alternative species for a wide range of furniture and other uses but possibly two – maple and sycamore – are close to ash in terms of flexibility and density. To dispel doubts about the quality and yield of some species such as alder and birch, the results of Teagasc tree improvement programmes which began in 2012 are showing positive results.

Michael Sommers inspects downy birch research plot in the townland of Coolbaun, Co Tipperary, planted in 1998. \Donal Magner

Somers is proud of the performance of a downy birch (Betula pubescens) research plot in the townland of Coolbaun, Co Tipperary, a short distance from the shore of Lough Derg. It is showing remarkable vigour and form. Planted in 1998, from 27 Irish provenances, this plot should provide commercial furniture lengths after two more thinnings. A nearby silver birch (B. pendula) trial of native and some German and French provenances is also promising.

Birch and alder tree improvement programmes demonstrate that commercial timber production is achievable over short rotations just like ash. Eventually an ash disease-resistant strain will also be achieved. “When that happens, the lesson learned is that ash will never be planted pure again,” says Power. “It is a species that works well in mixtures with other broadleaves and conifers, especially Norway spruce.”

SHARING OPTIONS