In 1956, US businessman Malcolm McLean invented the standardised shipping container, a simple idea that would transform global trade and the world economy. Up to that, loose cargo was loaded and unloaded from ships, crate by crate, at a cost of $5.86 per tonne.

McLean’s standardised shipping container (8ft tall, 8ft wide and 35ft long) that we know today slashed this cost for businesses to just $0.16/t.

While not as famous as Henry Ford, the Wright Brothers or Steve Jobs, McLean’s standardised shipping container had a profound impact across the globe, from the port of Dalian in China to Rotterdam to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

Innovations like McLean’s that change the world so dramatically are rare. In saying that, one company that is changing the world at this moment is Tesla, and its South African-born chief executive Elon Musk.

Working from an old General Motors and Toyota factory in California, Tesla is leading a renaissance in electric car manufacturing that looks set to have a far-reaching impact in the years ahead. Tesla launched its first electric car, the Model S, in 2012.

And similar to when Henry Ford launched the first mass-produced car, Tesla launched its Model 3 car last September, which is the company’s first mass market and affordable electric car.

Months before the car was even launched, Tesla had received almost $10bn worth of pre-orders for the Model 3 car from US consumers. The biggest challenge for the company is actually reaching a manufacturing scale to meet this demand.

And while the traditional car companies that manufacture combustible engines are rightly worried by the rise of Tesla, perhaps grain farmers in Ohio, Indiana and the rest of the US should be equally concerned.

The biofuels mandate

The fate of the US grain farmer has been intertwined with that of the oil industry since US Congress created the Renewable Fuel Standard in 2005 and expanded the programme in 2007 under the Energy Independence and Security Act. This new federal programme created a minimum mandate for biofuels to be used in all transportation fuel sold in the US.

The current mandate has recently been maintained by President Trump at 15bn US gallons, or the equivalent of about 357m barrels of oil per year. Fiercely opposed by the big oil companies, this mandate is set to more than double to 36bn gallons by 2022.

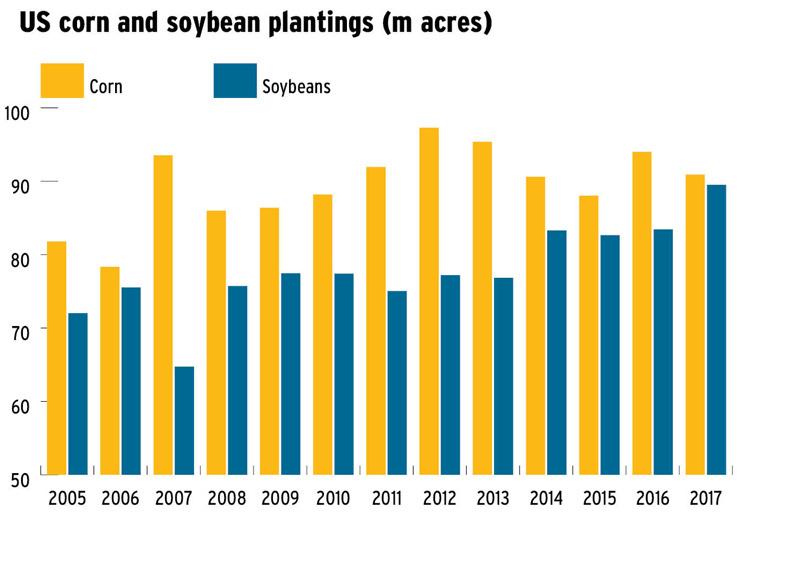

For US corn farmers, the Renewable Fuel Standard has made corn a feedstock of the oil industry, which created an increase in demand. The mandate currently accounts for approximately 120m tonnes of US corn, or one third of total US corn production. However, this increased demand has resulted in a major increase in US corn production over the last decade as farmers plant more acres.

Between 2000 and 2006, the average acreage planted in corn in the US was just over 79m acres. After the Renewable Fuel Standard was introduced, the average corn acreage over the last decade in the US has soared to 91m acres.

The planted corn acreage for 2018 is forecast at 91m acres again this year. Most of this extra corn production has been achieved through taking back acres that were previously set aside under the USDA conservation reserve program (CRP).

The bumper corn production in the US over recent years has served to keep corn prices on the floor, with Chicago prices repeatedly touching off decade lows of $3.20/bu ($125/t) over the last three years.

On average, corn prices have been around $3.50/bu ($138/t) in recent years, which would mean most farmers selling at harvest would have lost money. Corn futures for December 2018 are currently trading above $4/bu ($160/t) in Chicago, which would see farmers make money if realised.

Steady corn plantings

Yet despite the continuously weak price over the last three years, the attitude among US farmers has been to continue to plant corn and lots of it.

Even the attractive price for soybeans over recent years has done little to dissuade US farmers from planting their beloved corn crop. Instead, it is wheat that has suffered, with the USDA forecasting US spring and winter wheat plantings to fall to 45m acres in 2018 – the lowest area since 1919.

For the wider US agriculture sector, plentiful supplies of cheap corn is a major positive. US milk production has expanded steadily over recent years thanks to bountiful affordable corn supplies. For 2017, US milk production looks set to increase a further 1.6% above 94bn litres, with no sign of the milk tap easing off for 2018.

On the meat side, cheap corn has fuelled strong growth in US meat production. Since 2014, US meat production has increased more than 8% to reach 45m tonnes last year. For 2018, the USDA is forecasting US meat production to increase a further 3.5% to hit a record 47m tonnes.

But for how long more can US agriculture ride the wave of cheap corn? The US may have an enormous domestic market but the impact of cheap corn is undoubtedly felt across global agriculture, particularly for dairy and grain prices.

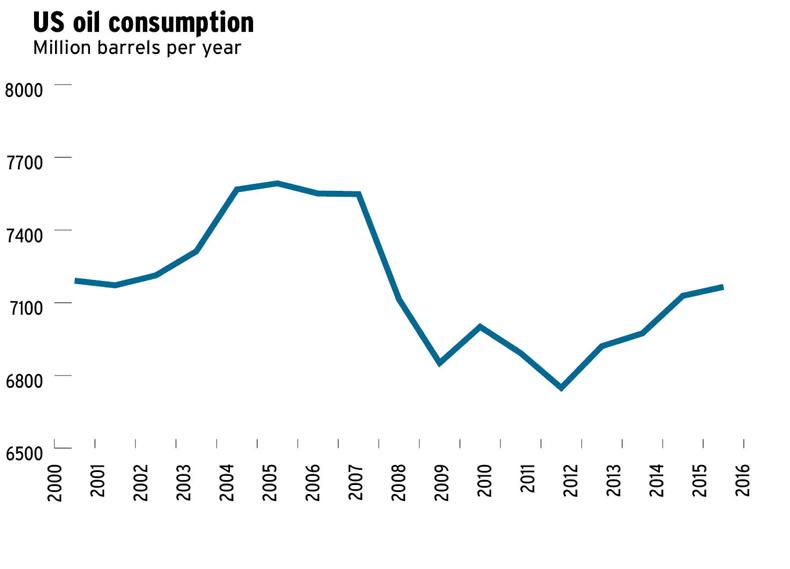

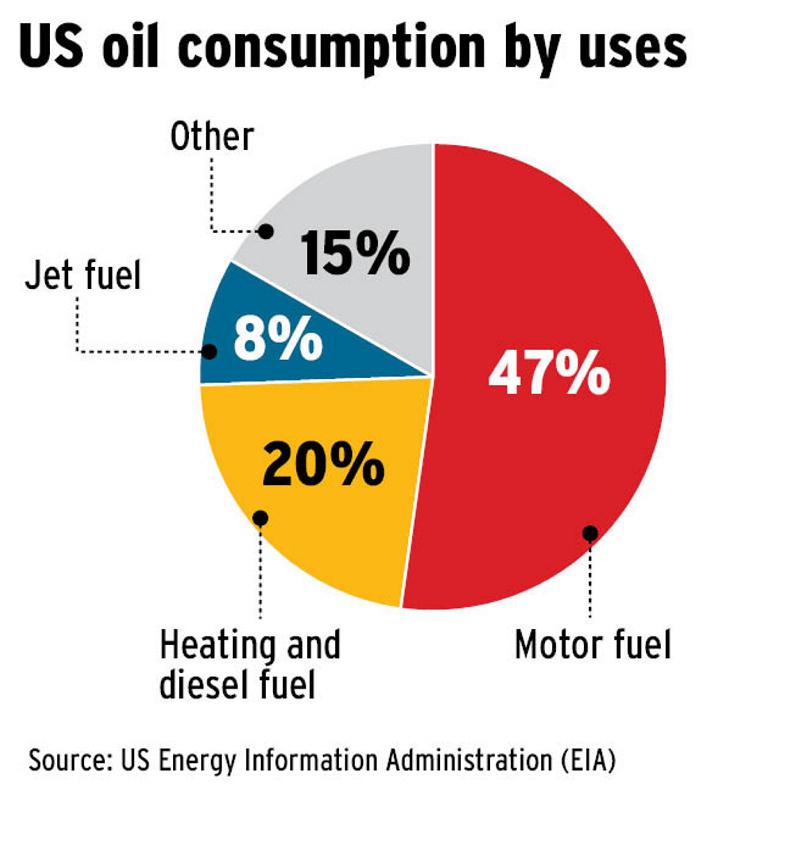

The reality is that Elon Musk and the Tesla electric car renaissance may have a huge impact on US agriculture in the years ahead. The US consumes about 7.2bn barrels of oil each year.

However, almost 50% of US oil consumption is accounted for by gas-guzzling motorists and the 264m registered vehicles in the US. Should Elon Musk and the electric revolution keep going in its current direction, the requirement for oil in the years ahead looks increasingly negative, not only in the US but all over the world.

Electric revolution

The big change created by Tesla could be the impact it has on the traditional car companies by pushing them towards electric. In July last year, Swedish car maker Volvo said it would only manufacture electric or hybrid vehicles from 2019 onwards, while Toyota has promised all of its cars will be electric or hybrid by 2025.

US car giant Ford has recently launched 15 new electric car models in China, while German automaker Volkswagen has committed €10bn to building electric cars in China.

Similarly, the hand of policy makers is being forced by the rise of the electric car. In France, President Macron has said the sale of new petrol or diesel cars will be banned from 2040, while the UK announced a similar plan from 2040.

Without the same demand for oil, where to for US corn farmers, even with a biofuels mandate? Will corn farmers in the US put the extra acres back into conservation or will they switch to oilseeds or other crops?

Global demand for corn is rising at 22m tonnes per annum over the past 20 years which should help partially offset any gaps left by the biofuels demand. The big risk for US agriculture is how rapidly the move to electric happens. If the change over time is gradual then markets and farmers will adjust accordingly. However, if the death of the internal combustion engine is as quick as the end to loose cargo shipping was in the 1950s, then a crash could be on the cards for US agriculture.

The rise of the electric car brings to mind the saying that the Stone Age didn’t end because the world ran out of stones and the oil age won’t end because the world runs out of oil. If the electric revolution continues on its current trajectory, it’s difficult to see how oil can maintain its relevance in the world economy.

From the perspective of Irish agriculture, this raises some very important questions. Oil economies are some of the biggest food importers in the world. In dairy alone, oil countries account for almost a third (30%) of all global dairy imports. The recent weakness in oil prices severely hit the buying power of consumers in these markets but we’ve seen more activity in the last year as the oil price recovered above $60/barrel once again.

But if the oil price was to be permanently damaged by the electric revolution then it poses serious challenges for Irish food exports, particularly our dairy industry. How will consumers in oil producing countries, where oil can account for as much as 90% of GDP, be able to afford Irish dairy in the future if the world’s appetite for oil starts to rapidly decline?

At a time when Irish dairy production is expanding rapidly and capital investments are being made in new capacity, industry leaders must consider the scenario where the customer landscape in the years ahead could be hugely different from what we know today.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: