It has been a very difficult spring across the country, but at this time of the year, things can change quickly, and when a burst of growth comes, grazing can soon get out of control.

“Everyone should walk their grazing platform, assess how much grass is there, and as soon as you can get to fields with both cows and with fertiliser, you should go. You stimulate grazing by grazing. It is not the time to hang around,” maintains Michael Calvert, farm business consultant with Promar International.

By getting cows out now, the aim is to create a grass wedge (a range of grass covers across the grazing platform). It means that when a flush of grass does come in May and June, you are still in a position to graze out properly, ideally down to around 1,500kg grass dry matter (DM) per hectare. “If you are going into swards above 3,000kg DM in those months, it is impossible to graze down to the target residual, and the rest of the grazing season becomes very challenging,” advises Michael.

The same principles apply to farmers who are considering taking out a significant proportion of the grazing platform as a first cut, in an attempt to replenish silage reserves. If it all comes out in one go, then you run the risk of a large block of land coming back into the cycle, that quickly gets ahead of cows. Better to stagger any silage making on the grazing platform over a period of a couple of weeks to help maintain that grass wedge.

McCay farm

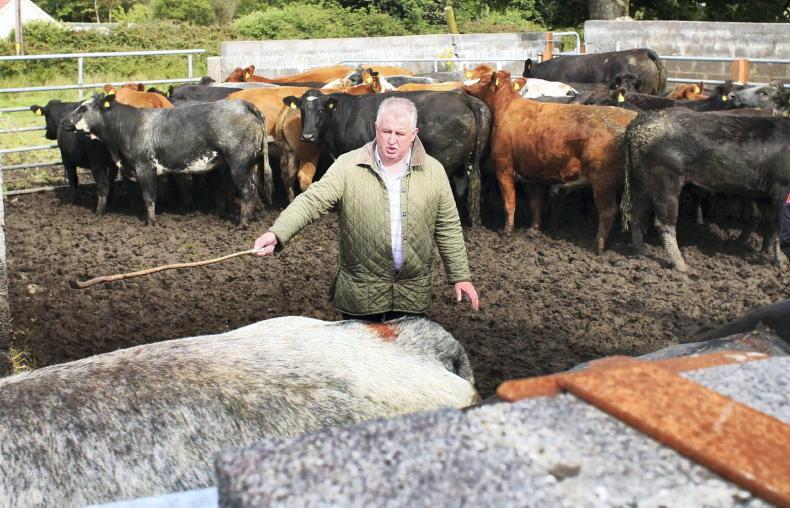

Getting on top of grazing this spring is the main aim of John McCay, who farms with his father Billy, and son Matthew, outside Castlederg, Co Tyrone.

The 315-cow herd is mainly spring calving, with cows mostly first-cross Fleckvieh breeding, producing an average of 6,200 litres.

Despite the very challenging conditions, the McCays have pressed on with getting cows out this spring, with turnout on 9 March, although that is nearly a month later than in previous years.

Since early March, the cows have only missed one day due to the rain. The farm is naturally dry, and while there probably has been more damage done this spring than the McCays would like, land type is such that fields will quickly recover when growth picks up.

To minimise damage through March and early April, cows go out hungry, so are keen to graze. They are out for four to five hours, and back inside by early afternoon. The grazing block is well set up with a network of laneways, and access points to paddocks.

Grass measurement is completed weekly by Michael Calvert, who inputs the information into Agrinet, and leaves the McCays with a grazing plan for the week ahead. Paddocks are not fixed in size – instead fields are split using a temporary electric fence depending on the area to be allocated at each grazing.

“Before we started using Michael’s services, we just went around the grazing block from one adjacent field to the next. We now go where Michael tells us. The key is to have a good infrastructure in place,” commented John.

Fertiliser

The grazing block received urea in February, although the response to that has been slow. A comprehensive liming policy means that the block is virtually all sitting at a pH above 6.0. Soil analysis shows that some fields are a little low in phosphorus (P) and potassium (K), and these areas are targeted with P containing fertiliser and/or a light coat of slurry after the first grazing.

Last year, the grazing block grew a very impressive 14.89t DM/ha. Any surplus during the season is taken out as bales. Some pre-mowing is also done during the summer, rather than topping grass after the cows.

The first two cuts of silage are put in the pit. A third cut is all baled.

With 315 cows on the 320ac farm, stocking rate is high at 2.46 cow equivalents per hectare. In 2017, cows produced 6,200 litres on 1.5t of concentrate fed. Milk from forage stood at 2,800 litres with a margin over concentrate of £1,400 per cow.

“We have had to feed more meal this spring than we would like, so it will be hard to improve on the milk from forage figure this year. But we still think there is more we can take out of the grazing platform. There are a few areas that need some drainage work done,” said John.

Concentrate

At present, cows are getting 7kg of concentrate through the wagon, and another 1kg in the parlour. The concentrate portion of the total mixed ration (TMR) is offered as a wet feed. That change in management came after a Fleckvieh trip to Germany, where the McCays were part of a group that visited a farm using the Danish method of compact feeding.

Each evening, concentrate feed is mixed with water at a rate of 1kg meal to one litre of water, and left to sit overnight in the wagon. It is then fed the next day.

According to the McCays, there is less sorting of feed by cows, and the animals are able to eat their fill more quickly, so will spend more time lying, which has a positive effect on milk yield.

Spring v autumn

The majority of the cows in the herd are spring calving. This year, calving started on 14 January and at the beginning of last week, 29 cows were left to calve. Calving will be complete by the end of the month.

Before breeding starts later this month, all cows will be scanned by a vet.

For the first six weeks of breeding, AI Fleckvieh bulls will be used, followed by another six weeks of AI with a beef bull. A stock beef bull will then sweep up for the final three weeks.

An autumn-calving herd of 60 cows is also kept, and it follows a similar breeding regime, except breeding is over a 12-week period, rather than 15 weeks.

But why keep an autumn calving herd at all? “It splits the workload and keeps milk in the tank. We are in the yard anyway, and with a 30-point parlour, milking two rows isn’t torture. But down the line, we will probably go all spring-calving,” responded John.

The autumn and spring cows are not separated when in-milk. The only group kept separate are the last 20 cows to calve, which get some extra attention in the spring, and given time to transition, before joining the main herd.

“We try to keep things as simple as possible. If it gets complicated, it won’t be done,” said John.

Cow type

The other question many farmers will probably have is around cow type. The McCays previously worked with Holstein Friesian cows, but increasingly became frustrated with a high empty rate at the end of the breeding season (in some years as high as 30%).

Around eight years ago, they bought-in some Fleckvieh cows, and some calves, and starting using Fleckvieh semen through AI. It means that a lot of the cows currently on the farm are Fleckvieh cross Holstein.

The downside is probably the high weights of some of the cows. But crossing has significantly improved fertility. According to John, the cows show strong heats at bulling. Calving interval currently stands at an excellent 373 days. Only eight empty cows were culled last year.

“We are happy with the Fleckvieh, but we are also open to trying various things. We have used bits of Red Holstein, Normande, Norwegian Red. I have also recently used some high EBI bulls from the Republic of Ireland,” said John.

Where the Fleckvieh definitely does score over other breeds is in the value of the resultant bull calves. The McCays normally receive around £230 to £250 for a bull calf at under three weeks.

315 Fleckvieh-bred cows.320 acres farmed.167ac grazing platform.6,200 litres per cow.4.2% butterfat.3.4% protein.373-day calving interval.1.5t meal fed per cow. Read more

Monday Management: Change in weather but challenges remain

Put 1t silage/cow in reserve – Teagasc

It has been a very difficult spring across the country, but at this time of the year, things can change quickly, and when a burst of growth comes, grazing can soon get out of control.

“Everyone should walk their grazing platform, assess how much grass is there, and as soon as you can get to fields with both cows and with fertiliser, you should go. You stimulate grazing by grazing. It is not the time to hang around,” maintains Michael Calvert, farm business consultant with Promar International.

By getting cows out now, the aim is to create a grass wedge (a range of grass covers across the grazing platform). It means that when a flush of grass does come in May and June, you are still in a position to graze out properly, ideally down to around 1,500kg grass dry matter (DM) per hectare. “If you are going into swards above 3,000kg DM in those months, it is impossible to graze down to the target residual, and the rest of the grazing season becomes very challenging,” advises Michael.

The same principles apply to farmers who are considering taking out a significant proportion of the grazing platform as a first cut, in an attempt to replenish silage reserves. If it all comes out in one go, then you run the risk of a large block of land coming back into the cycle, that quickly gets ahead of cows. Better to stagger any silage making on the grazing platform over a period of a couple of weeks to help maintain that grass wedge.

McCay farm

Getting on top of grazing this spring is the main aim of John McCay, who farms with his father Billy, and son Matthew, outside Castlederg, Co Tyrone.

The 315-cow herd is mainly spring calving, with cows mostly first-cross Fleckvieh breeding, producing an average of 6,200 litres.

Despite the very challenging conditions, the McCays have pressed on with getting cows out this spring, with turnout on 9 March, although that is nearly a month later than in previous years.

Since early March, the cows have only missed one day due to the rain. The farm is naturally dry, and while there probably has been more damage done this spring than the McCays would like, land type is such that fields will quickly recover when growth picks up.

To minimise damage through March and early April, cows go out hungry, so are keen to graze. They are out for four to five hours, and back inside by early afternoon. The grazing block is well set up with a network of laneways, and access points to paddocks.

Grass measurement is completed weekly by Michael Calvert, who inputs the information into Agrinet, and leaves the McCays with a grazing plan for the week ahead. Paddocks are not fixed in size – instead fields are split using a temporary electric fence depending on the area to be allocated at each grazing.

“Before we started using Michael’s services, we just went around the grazing block from one adjacent field to the next. We now go where Michael tells us. The key is to have a good infrastructure in place,” commented John.

Fertiliser

The grazing block received urea in February, although the response to that has been slow. A comprehensive liming policy means that the block is virtually all sitting at a pH above 6.0. Soil analysis shows that some fields are a little low in phosphorus (P) and potassium (K), and these areas are targeted with P containing fertiliser and/or a light coat of slurry after the first grazing.

Last year, the grazing block grew a very impressive 14.89t DM/ha. Any surplus during the season is taken out as bales. Some pre-mowing is also done during the summer, rather than topping grass after the cows.

The first two cuts of silage are put in the pit. A third cut is all baled.

With 315 cows on the 320ac farm, stocking rate is high at 2.46 cow equivalents per hectare. In 2017, cows produced 6,200 litres on 1.5t of concentrate fed. Milk from forage stood at 2,800 litres with a margin over concentrate of £1,400 per cow.

“We have had to feed more meal this spring than we would like, so it will be hard to improve on the milk from forage figure this year. But we still think there is more we can take out of the grazing platform. There are a few areas that need some drainage work done,” said John.

Concentrate

At present, cows are getting 7kg of concentrate through the wagon, and another 1kg in the parlour. The concentrate portion of the total mixed ration (TMR) is offered as a wet feed. That change in management came after a Fleckvieh trip to Germany, where the McCays were part of a group that visited a farm using the Danish method of compact feeding.

Each evening, concentrate feed is mixed with water at a rate of 1kg meal to one litre of water, and left to sit overnight in the wagon. It is then fed the next day.

According to the McCays, there is less sorting of feed by cows, and the animals are able to eat their fill more quickly, so will spend more time lying, which has a positive effect on milk yield.

Spring v autumn

The majority of the cows in the herd are spring calving. This year, calving started on 14 January and at the beginning of last week, 29 cows were left to calve. Calving will be complete by the end of the month.

Before breeding starts later this month, all cows will be scanned by a vet.

For the first six weeks of breeding, AI Fleckvieh bulls will be used, followed by another six weeks of AI with a beef bull. A stock beef bull will then sweep up for the final three weeks.

An autumn-calving herd of 60 cows is also kept, and it follows a similar breeding regime, except breeding is over a 12-week period, rather than 15 weeks.

But why keep an autumn calving herd at all? “It splits the workload and keeps milk in the tank. We are in the yard anyway, and with a 30-point parlour, milking two rows isn’t torture. But down the line, we will probably go all spring-calving,” responded John.

The autumn and spring cows are not separated when in-milk. The only group kept separate are the last 20 cows to calve, which get some extra attention in the spring, and given time to transition, before joining the main herd.

“We try to keep things as simple as possible. If it gets complicated, it won’t be done,” said John.

Cow type

The other question many farmers will probably have is around cow type. The McCays previously worked with Holstein Friesian cows, but increasingly became frustrated with a high empty rate at the end of the breeding season (in some years as high as 30%).

Around eight years ago, they bought-in some Fleckvieh cows, and some calves, and starting using Fleckvieh semen through AI. It means that a lot of the cows currently on the farm are Fleckvieh cross Holstein.

The downside is probably the high weights of some of the cows. But crossing has significantly improved fertility. According to John, the cows show strong heats at bulling. Calving interval currently stands at an excellent 373 days. Only eight empty cows were culled last year.

“We are happy with the Fleckvieh, but we are also open to trying various things. We have used bits of Red Holstein, Normande, Norwegian Red. I have also recently used some high EBI bulls from the Republic of Ireland,” said John.

Where the Fleckvieh definitely does score over other breeds is in the value of the resultant bull calves. The McCays normally receive around £230 to £250 for a bull calf at under three weeks.

315 Fleckvieh-bred cows.320 acres farmed.167ac grazing platform.6,200 litres per cow.4.2% butterfat.3.4% protein.373-day calving interval.1.5t meal fed per cow. Read more

Monday Management: Change in weather but challenges remain

Put 1t silage/cow in reserve – Teagasc

SHARING OPTIONS