Methane is the most significant greenhouse gas emitted by cows. It is mostly emitted from the mouth through belching, with a smaller amount released as flatulence (cow farts) and in slurry. It is true that methane is harmful to our atmosphere, but significant work is underway to develop new methods to capture it or reduce its production.

Methane gas is an important fuel source and is used daily to heat our homes and businesses, as well as to generate electricity. This, of course is natural gas. Natural gas is methane which has been extracted from gas fields off the coast of Ireland or multiple other locations around the world. However, natural gas is a fossil fuel, and drilling, extracting, cleaning and burning this methane results in significant emissions to our atmosphere.

Under Ireland’s emission reduction plans, we have to reduce our natural gas usage. This could either mean installing electrical heating systems and using renewable electricity or, as many businesses aim to do, transitioning to renewable methane, known as biomethane.

Over the coming years, Ireland will be capturing methane from animal slurry, cleaning it to create biomethane, and using it as a substitute for natural gas. This can be done in what are known as anaerobic digestion plants.

What is anaerobic digestion?

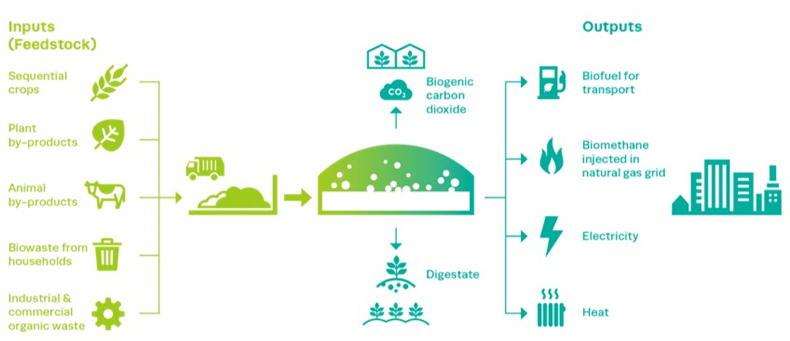

Anaerobic digestion is the natural breakdown of any organic material such as slurry, crops, or food waste by microorganisms in the absence of oxygen.

This organic material, called feedstock, is broken down, releasing biogas. Biogas is approximately 55% methane, 40% carbon dioxide, and 5% other gases.

This process can be controlled and managed in purpose-built and sealed metal or concrete tanks known as anaerobic digestion plants, where the biogas, which would otherwise escape into the atmosphere, is captured.

The anaerobic digestion process. /Source EBA

Biomethane is created when the carbon dioxide and other gases are removed from biogas, and methane is concentrated to around 97%. Biomethane is virtually chemically identical to natural gas. The CO2 can also be captured and sold as an ingredient for fizzy drinks, beer, or other industrial uses.

Most of what goes into an anaerobic digestion tank comes out the other end in the form of digestate. Digestate is a slurry-like organic material left over after the anaerobic digestion process takes place. It is rich in available nutrients, which can be used to grow grass and crops.

Ireland’s industry

Anaerobic digestion plants are very common across Europe, with over 21,000 in operation. There are nearly 90 in operation in Northern Ireland. However, here in the Republic of Ireland, there are around ten, with some producing biomethane and some producing electricity. However, under Ireland’s climate action plan, the country must develop approximately 140-200 new anaerobic digestion plants by the end of the decade.

The task is massive, if not impossible in that time frame. But there certainly will be a handful of new anaerobic digestion plants built. Many are now in the planning process.

What does it mean for farmers?

Developing new anaerobic digestion plants will mean several things. Firstly, it will provide a new market for slurry and will help dairy farmers deal with their derogation challenges. It will also create a new market for crops such as wholecrop cereals, grass silage, beet, maize, etc., and farmers will be contracted to grow these. It will also provide a source of organic nutrients for farmers, particularly farms which import nutrients like tillage farms.

Farmers can, of course, seek to build their own plants, but given that it costs millions of euros, that is very challenging. There is scope for farmers to come together and work with their cooperatives or form a new cooperative; however, this is unlikely to happen until the industry gets up and going. If the 2030 anaerobic digestion targets are met, then it is expected that two million tonnes of CO2 per year would be saved.

Methane is the most significant greenhouse gas emitted by cows. It is mostly emitted from the mouth through belching, with a smaller amount released as flatulence (cow farts) and in slurry. It is true that methane is harmful to our atmosphere, but significant work is underway to develop new methods to capture it or reduce its production.

Methane gas is an important fuel source and is used daily to heat our homes and businesses, as well as to generate electricity. This, of course is natural gas. Natural gas is methane which has been extracted from gas fields off the coast of Ireland or multiple other locations around the world. However, natural gas is a fossil fuel, and drilling, extracting, cleaning and burning this methane results in significant emissions to our atmosphere.

Under Ireland’s emission reduction plans, we have to reduce our natural gas usage. This could either mean installing electrical heating systems and using renewable electricity or, as many businesses aim to do, transitioning to renewable methane, known as biomethane.

Over the coming years, Ireland will be capturing methane from animal slurry, cleaning it to create biomethane, and using it as a substitute for natural gas. This can be done in what are known as anaerobic digestion plants.

What is anaerobic digestion?

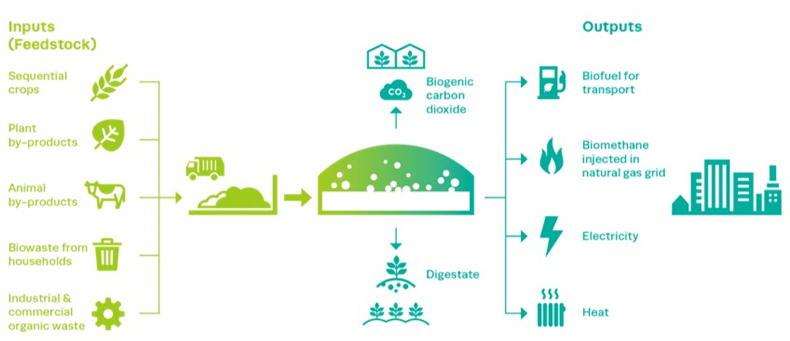

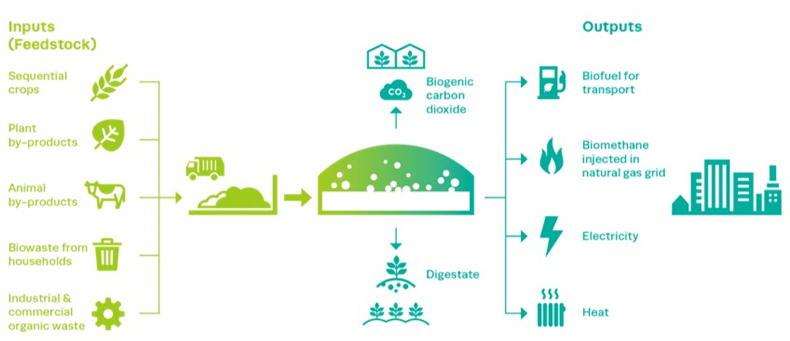

Anaerobic digestion is the natural breakdown of any organic material such as slurry, crops, or food waste by microorganisms in the absence of oxygen.

This organic material, called feedstock, is broken down, releasing biogas. Biogas is approximately 55% methane, 40% carbon dioxide, and 5% other gases.

This process can be controlled and managed in purpose-built and sealed metal or concrete tanks known as anaerobic digestion plants, where the biogas, which would otherwise escape into the atmosphere, is captured.

The anaerobic digestion process. /Source EBA

Biomethane is created when the carbon dioxide and other gases are removed from biogas, and methane is concentrated to around 97%. Biomethane is virtually chemically identical to natural gas. The CO2 can also be captured and sold as an ingredient for fizzy drinks, beer, or other industrial uses.

Most of what goes into an anaerobic digestion tank comes out the other end in the form of digestate. Digestate is a slurry-like organic material left over after the anaerobic digestion process takes place. It is rich in available nutrients, which can be used to grow grass and crops.

Ireland’s industry

Anaerobic digestion plants are very common across Europe, with over 21,000 in operation. There are nearly 90 in operation in Northern Ireland. However, here in the Republic of Ireland, there are around ten, with some producing biomethane and some producing electricity. However, under Ireland’s climate action plan, the country must develop approximately 140-200 new anaerobic digestion plants by the end of the decade.

The task is massive, if not impossible in that time frame. But there certainly will be a handful of new anaerobic digestion plants built. Many are now in the planning process.

What does it mean for farmers?

Developing new anaerobic digestion plants will mean several things. Firstly, it will provide a new market for slurry and will help dairy farmers deal with their derogation challenges. It will also create a new market for crops such as wholecrop cereals, grass silage, beet, maize, etc., and farmers will be contracted to grow these. It will also provide a source of organic nutrients for farmers, particularly farms which import nutrients like tillage farms.

Farmers can, of course, seek to build their own plants, but given that it costs millions of euros, that is very challenging. There is scope for farmers to come together and work with their cooperatives or form a new cooperative; however, this is unlikely to happen until the industry gets up and going. If the 2030 anaerobic digestion targets are met, then it is expected that two million tonnes of CO2 per year would be saved.

SHARING OPTIONS