A sustainable level of livestock production may be found in Europe if we define more clearly its contribution to human needs and environmental, health and animal welfare impacts, a new study claims.

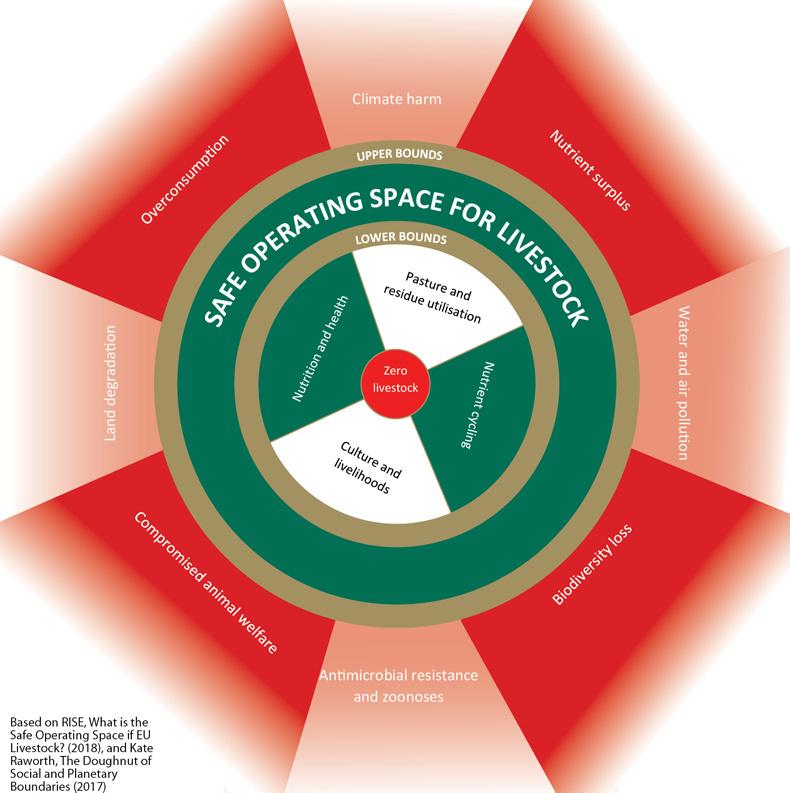

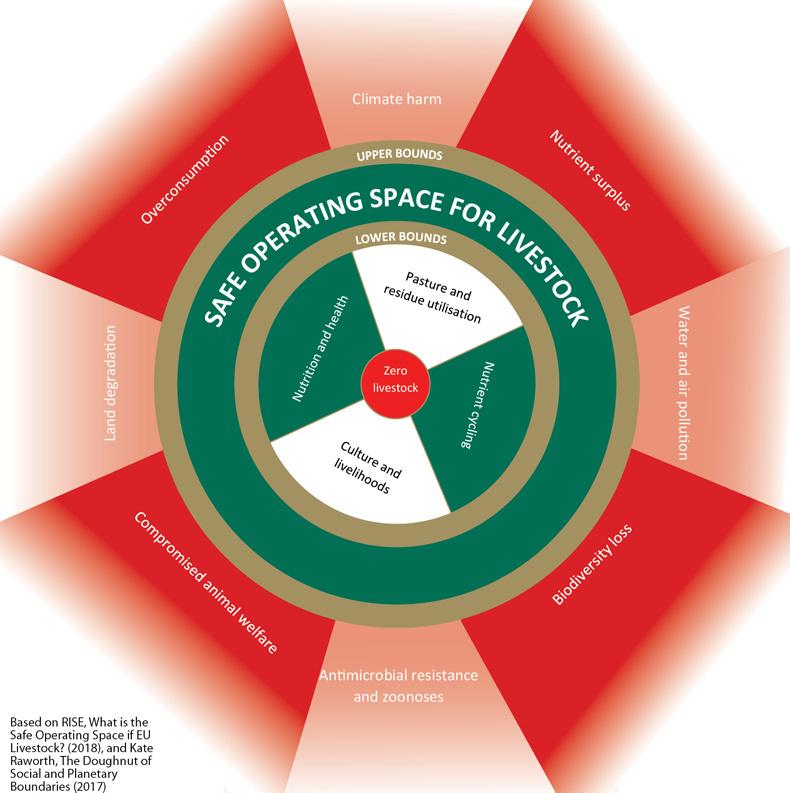

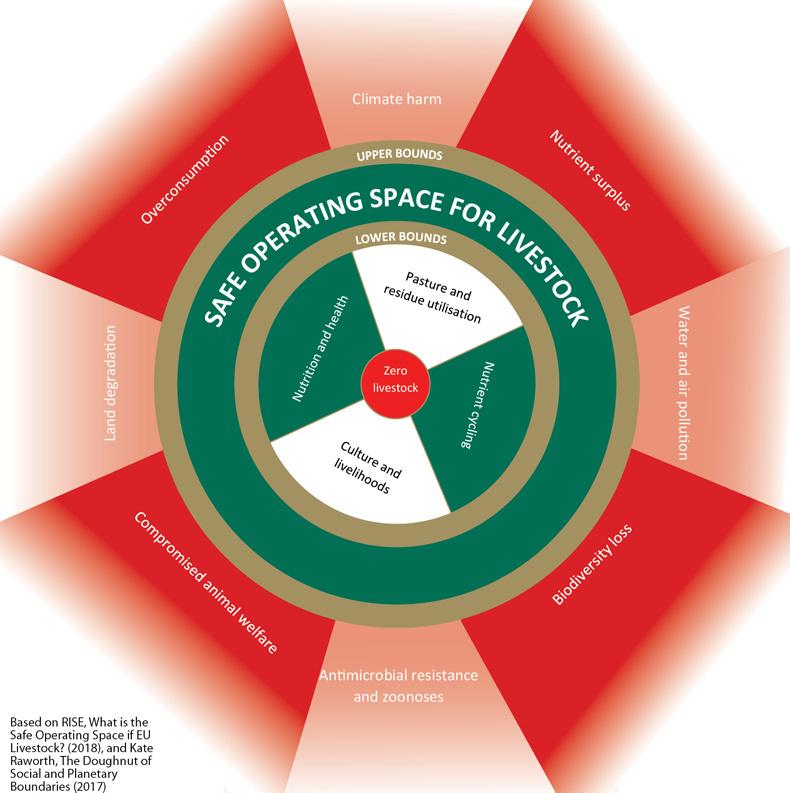

The paper attempts to define a “safe operating space for EU livestock” and was published by the Rural Investment Support for Europe (RISE) foundation, a think tank founded by former European Commissioner for Agriculture Franz Fischler with larger players in EU agri-food on its board. The authors, led by British agricultural economist Allan Buckwell, apply to livestock farming the work of a number of academics. These include Johan Rockström, who introduced the idea of planetary boundaries capping how much we can draw from the Earth, and Kate Raworth, who added that people need to satisfy their basic needs. This leaves a doughnut-shaped space for mankind to thrive (see graphic).

On the one hand, we need livestock to produce nutritious food – especially in “large land areas not suitable for crop cultivation”, maintain permanent pastures, recycle byproducts in animal feed, support the rural economy and enjoy our cultural connection to farm animals. The only scientifically defined target here is nutrition. Despite strong national variations, the study found that dairy consumption in Europe is broadly in line with dietary recommendations, but only 40% to 60% of the meat we eat is necessary. Meanwhile, a “conservative estimate” is that half of current EU livestock numbers is the minimum required to maintain permanent pastures.

On the other hand, the study argues that excessive livestock farming contributes to the degradation of soils and biodiversity, nutrient loss and pollution, animal health and welfare issues such as antimicrobial resistance, and there is evidence that eating too much red or processed meat is bad for human health. They have not found ways of measuring safe livestock numbers for these issues, though they estimate nutrient flows to be outside acceptable boundaries, especially in Ireland.

Greenhouse gas emissions contributing to climate change are the only constraint currently defined by science and policy. The authors calculated that if livestock farming was to contribute in the same way as other industries to EU targets set under the 2015 Paris Agreement, its emissions would need to fall by 74% by 2050. This means a constant 3.5% annual cut in emissions. “This is an extremely challenging task,” the study found. Although progress is being made in breeding and feeding, such gains have never been seen in agriculture. They also argue that the minimum number of animals required to meet Europeans’ dietary recommendations and maintain pastures appears to be higher than the upper limit for the sector to meet climate targets.

Uncomfortable choices

“These findings imply uncomfortable choices for society,” they wrote. They recommend using the CAP to support “structural change” in livestock farming, including better integration with tillage.

They also suggest encouraging consumption of alternative proteins in food and feed. “As this happens livestock numbers will probably fall, the resource efficiency of remaining livestock improve and leakages and waste reduce,” they wrote. They acknowledge that the resulting safe operating space for livestock will look different in various EU countries: “Some livestock activity will have to contract and disappear, some will have to relocate, change size, change technology – feed and feed system, housing manure management, and some businesses may grow.” The study also recognised the risk that rising imports might displace negative impacts to countries with lower standards, but wrote that this could be measured and stopped by international rules such as the Paris Agreement.

Read more

Use AD to produce gas, reduce emissions and grow more grass – SEAI

Expansion and climate targets are ‘incompatible’

Watch: no climate tax on cattle

A sustainable level of livestock production may be found in Europe if we define more clearly its contribution to human needs and environmental, health and animal welfare impacts, a new study claims.

The paper attempts to define a “safe operating space for EU livestock” and was published by the Rural Investment Support for Europe (RISE) foundation, a think tank founded by former European Commissioner for Agriculture Franz Fischler with larger players in EU agri-food on its board. The authors, led by British agricultural economist Allan Buckwell, apply to livestock farming the work of a number of academics. These include Johan Rockström, who introduced the idea of planetary boundaries capping how much we can draw from the Earth, and Kate Raworth, who added that people need to satisfy their basic needs. This leaves a doughnut-shaped space for mankind to thrive (see graphic).

On the one hand, we need livestock to produce nutritious food – especially in “large land areas not suitable for crop cultivation”, maintain permanent pastures, recycle byproducts in animal feed, support the rural economy and enjoy our cultural connection to farm animals. The only scientifically defined target here is nutrition. Despite strong national variations, the study found that dairy consumption in Europe is broadly in line with dietary recommendations, but only 40% to 60% of the meat we eat is necessary. Meanwhile, a “conservative estimate” is that half of current EU livestock numbers is the minimum required to maintain permanent pastures.

On the other hand, the study argues that excessive livestock farming contributes to the degradation of soils and biodiversity, nutrient loss and pollution, animal health and welfare issues such as antimicrobial resistance, and there is evidence that eating too much red or processed meat is bad for human health. They have not found ways of measuring safe livestock numbers for these issues, though they estimate nutrient flows to be outside acceptable boundaries, especially in Ireland.

Greenhouse gas emissions contributing to climate change are the only constraint currently defined by science and policy. The authors calculated that if livestock farming was to contribute in the same way as other industries to EU targets set under the 2015 Paris Agreement, its emissions would need to fall by 74% by 2050. This means a constant 3.5% annual cut in emissions. “This is an extremely challenging task,” the study found. Although progress is being made in breeding and feeding, such gains have never been seen in agriculture. They also argue that the minimum number of animals required to meet Europeans’ dietary recommendations and maintain pastures appears to be higher than the upper limit for the sector to meet climate targets.

Uncomfortable choices

“These findings imply uncomfortable choices for society,” they wrote. They recommend using the CAP to support “structural change” in livestock farming, including better integration with tillage.

They also suggest encouraging consumption of alternative proteins in food and feed. “As this happens livestock numbers will probably fall, the resource efficiency of remaining livestock improve and leakages and waste reduce,” they wrote. They acknowledge that the resulting safe operating space for livestock will look different in various EU countries: “Some livestock activity will have to contract and disappear, some will have to relocate, change size, change technology – feed and feed system, housing manure management, and some businesses may grow.” The study also recognised the risk that rising imports might displace negative impacts to countries with lower standards, but wrote that this could be measured and stopped by international rules such as the Paris Agreement.

Read more

Use AD to produce gas, reduce emissions and grow more grass – SEAI

Expansion and climate targets are ‘incompatible’

Watch: no climate tax on cattle

SHARING OPTIONS