First things first, the ‘Farm Zero C’ project is successfully driving down the carbon number.

The two big areas where the latest gains have been made are reducing fertiliser usage and reducing the feed production number.

According to Padraig Walsh, Farm Zero C project manager, the carbon emissions number for feed production on the farm has gone from 0.15 to 0.05kg CO2 equivalent per kilo milk solids since 2018. This figure suggests the emissions intensity for every kilo of solids corrected milk produced is now 0.05kg of carbon.

This reduction is achieved by reducing concentrate use, incorporating more grass into the diet and switching to native grains.

The fertiliser carbon number is down from 0.13 to 0.05kg CO2 equivalent per kilo milk solids. This is due to 100% use of protected urea and the drop in usage from 248kg N /ha to 114kg N /ha in 2023. These numbers are not from the AgNav. They are calculated using a UCD model independently verified by ISO.

On the money side, Teagasc specialist Don Crowley said the cash inside the current account at the end of the year after everyone is paid was €369 per cow in 2023.

So, that’s €90,000 cash for milking the 240 cows, paying all labour, paying land rent (€52,000) and getting no single farm payment (BISS).

Net milk price was 50c/l in 2023 and total costs were €2,556/cow (€618,552).

In terms of the new environmental research measures, the slurry and feed additives are not charged to the farm.

On soil, University College Cork’s William Burchill discussed the fact that 89% of the farm at Shinagh is over 6.2pH. That’s a huge asset when clover is a key part in the sward mix. Also, the farm has excellent phosphorus and potassium reserves with over 75% of the farm soils at index 3 and 4 for P and K.

On the same stand, Teagasc’s Ben Lahart talked about the feed additives they have on trial (Bovaer 3 NOP) and the fact that they are still searching for a solution to get a methane inhibitor into cows at grass.

The current Irish research clearly shows methane emissions reducing for the two hours after milking when cows have been fed, but after that it returns to more normal output levels.

So, instead of the 30% methane emissions reduction when cows are fed indoors on a total mixed ration (TMR) diet, the grazing cows only getting meal in the parlour achieve a 5% reduction overall.

So the research continues to see if they can get this product into a slow-release bolus or water system.

James Gaffey, Munster Technological University, talked about the grass biorefinery project that is part of the overall Farm Zero C project. This is where they are mechanically pressing grass that results in a high protein liquid and a fibrous feed.

This feed perhaps might be used as a silage for ruminants and, already, the high protein fraction has been used in pig weaner diets to replace soya and there is the potential that it might make a human grade protein.

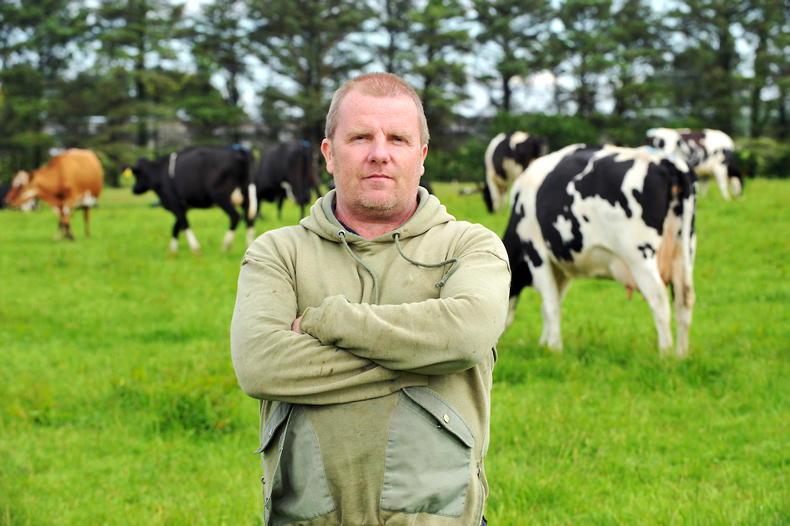

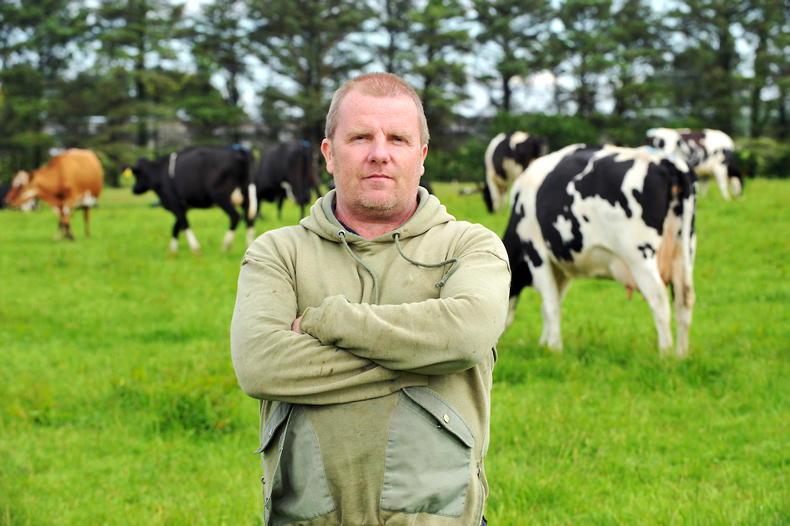

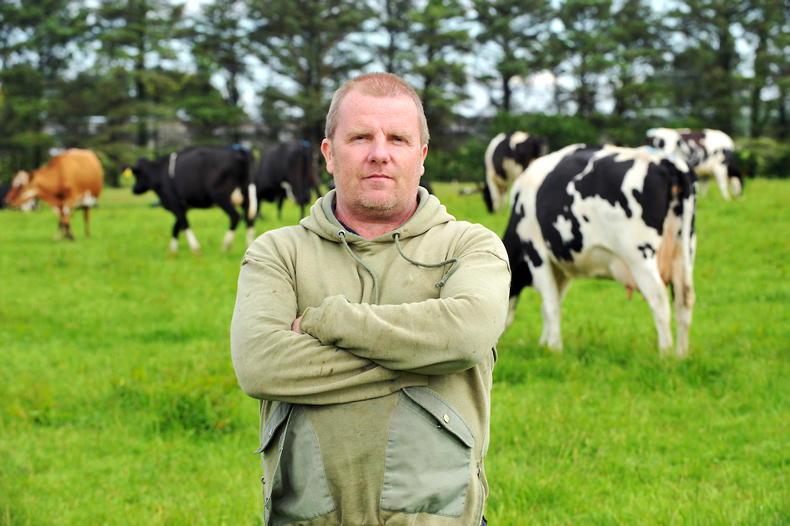

Kevin Ahern, Shinagh Dairy Farm.

“There is five times lower carbon footprint on the grass-based protein source than imported soya from south America” – James Gaffey, MTU“We have seen a 27% reduction in the carbon number to date below the 2018 baseline with milk from 0.86 to 0.63/kg fat corrected milk. Ammonia is down 55%” - Padraig Walsh, Farm Zero C project manager“We are growing multispecies over four years now and we still don’t have enough information to answer if they are doing enough for us – we’ll leave that to Curtins Farm. On red clover we have one field that hasn’t got bag N in four years and we get four cuts per year but another not so good that needed 100kg of nitrogen/ha this year. Cows were scanned and not in-calf cows sold within 48 hours to reduce stocking rate” – Kevin Ahern, farm manager“The cows on multispecies do a lot more urinating, that’s for sure – you’d see it in the parlour. So perhaps they are spreading nitrogen more often in the field” – Kevin Ahern, farm managerUsing clover and multispecies to reduce nitrogen.Chemically amending slurry with GasAbate from GlasPortBio.Feeding methane additive (Bovaer) during housing.17% of grazing area in multispecies.63% of farm has over 20% clover in sward.Performance

16 litres (4.95% fat and 4.03% protein or 1.4 kg MS/cow).Feed 2kg of meal plus grazing.7.6% of cows scanned empty and 16% of heifers (contract reared).Grass grown to date: nine tonnes and hoping to hit 11.5 tonnes for the year (901kg AFC and 330/LU).

Multispecies and clover have been growing on the Shinagh Farm for the last four years but, like all farms, it was slow to get going this year.

The Shinagh Farm is owned indirectly by the four west Cork dairy co-ops. The farm started in 2011 as a demonstration farm pre-quota removal similar to the Greenfield Farm in Kilkenny that started in 2009. Kevin Ahern is farm manager and has been since the start of the project. Over the last number of years, the farm has evolved into more research rather than demonstration, seeking and trialling solutions for decarbonising Irish dairy farming.

The learning

curve continues

There was a written comment on the first board – “the carbon footprint reduction from the project has not negatively impacted farm performance.”

That’s a big statement when just above that you have the fact the farm has grown nine tonnes per hectare to date and purchased 54 acres of silage for winter feed.

Of course, 2024 was a difficult year for all farms, but there are signs that the lower nitrogen is already leading to higher concentrate feeding and more forage purchases. This is despite the fact that the farm has dropped stocking rate.

It is great to have long-term commercial farm studies like this. It allows for real medium- to long-term results to be established replicating what happens on most Irish farms. If we look back over the last 10 years of Shinagh, I believe we can see a real difference emerging between the old-fashioned dairy management compared to the fancy, new lower nitrogen blueprint.

From 2013 to 2017 inclusive, the Shinagh Farm averaged close to 15 tonnes of dry matter grown, meal input was relatively low averaging less than 500kg of meal per cow, and artificial nitrogen input was in the region of 200kg/ha to 250kg/ha.

From 2018, the nitrogen input has started to be reduced, more clover and multispecies were coming into the grazing mix and red clover was been introduced on silage ground.

The perceived environmental measures might well be moving in the right direction, but the unbalanced stool means it’s an uncomfortable seat for farmers

The net effect in terms of feed stocks is that silage for winter feed had to be purchased in at least three of the years, meal fed per cow is closer to 1,000kg per cow and ‘average’ grass grown is closer to 12 tonnes of dry matter per hectare.

Stocking rate was reduced from the previous 2.9 cows/ha norm closer to 2.5 cows/ha. However, the grass grown is still not able to meet the annual feed demands of the stock.

At the walk and afterwards, I spoke to progressive dairy farmers who have been trying to get more clover into swards, trying red clover and multispecies.

The message was similar – the consistency of delivery in this low nitrogen world is not there yet and the risk of a feed deficit during grazing or a deficit of winter feed is much higher.

All were clearly in favour of improving the environmental credentials and have been working hard in this space. However, they said if the three legs of the stool are economic, social and environmental, they are finding problems with the stress (social) of the new system and the economic reality.

Over 11 organisations collaborate in this project co-led by Carbery and BiOrbic.

The perceived environmental measures might well be moving in the right direction, but the unbalanced stool means it’s an uncomfortable seat for farmers. Perhaps the very difficult 2024 grass year is impacting opinions, but I was clearly left with the message that year after year, these farmers are finding the system much more difficult to manage.

In reality, these farms are adjusting to a 25% reduction in feed grown on farm.

The 85 hectares just outside Bandon were producing 1,275 tonnes of feed per year and now it’s closer to 1,000 tonnes of feed.

Yes, the purchased nitrogen input to produce the 1,000 tonnes is less, but with that there is a lot more risk.

Maybe two cows per hectare is closer to where they need to be to match growth rates?

The two big areas where the latest gains have been made are reducing fertiliser usage and reducing the feed production number.

First things first, the ‘Farm Zero C’ project is successfully driving down the carbon number.

The two big areas where the latest gains have been made are reducing fertiliser usage and reducing the feed production number.

According to Padraig Walsh, Farm Zero C project manager, the carbon emissions number for feed production on the farm has gone from 0.15 to 0.05kg CO2 equivalent per kilo milk solids since 2018. This figure suggests the emissions intensity for every kilo of solids corrected milk produced is now 0.05kg of carbon.

This reduction is achieved by reducing concentrate use, incorporating more grass into the diet and switching to native grains.

The fertiliser carbon number is down from 0.13 to 0.05kg CO2 equivalent per kilo milk solids. This is due to 100% use of protected urea and the drop in usage from 248kg N /ha to 114kg N /ha in 2023. These numbers are not from the AgNav. They are calculated using a UCD model independently verified by ISO.

On the money side, Teagasc specialist Don Crowley said the cash inside the current account at the end of the year after everyone is paid was €369 per cow in 2023.

So, that’s €90,000 cash for milking the 240 cows, paying all labour, paying land rent (€52,000) and getting no single farm payment (BISS).

Net milk price was 50c/l in 2023 and total costs were €2,556/cow (€618,552).

In terms of the new environmental research measures, the slurry and feed additives are not charged to the farm.

On soil, University College Cork’s William Burchill discussed the fact that 89% of the farm at Shinagh is over 6.2pH. That’s a huge asset when clover is a key part in the sward mix. Also, the farm has excellent phosphorus and potassium reserves with over 75% of the farm soils at index 3 and 4 for P and K.

On the same stand, Teagasc’s Ben Lahart talked about the feed additives they have on trial (Bovaer 3 NOP) and the fact that they are still searching for a solution to get a methane inhibitor into cows at grass.

The current Irish research clearly shows methane emissions reducing for the two hours after milking when cows have been fed, but after that it returns to more normal output levels.

So, instead of the 30% methane emissions reduction when cows are fed indoors on a total mixed ration (TMR) diet, the grazing cows only getting meal in the parlour achieve a 5% reduction overall.

So the research continues to see if they can get this product into a slow-release bolus or water system.

James Gaffey, Munster Technological University, talked about the grass biorefinery project that is part of the overall Farm Zero C project. This is where they are mechanically pressing grass that results in a high protein liquid and a fibrous feed.

This feed perhaps might be used as a silage for ruminants and, already, the high protein fraction has been used in pig weaner diets to replace soya and there is the potential that it might make a human grade protein.

Kevin Ahern, Shinagh Dairy Farm.

“There is five times lower carbon footprint on the grass-based protein source than imported soya from south America” – James Gaffey, MTU“We have seen a 27% reduction in the carbon number to date below the 2018 baseline with milk from 0.86 to 0.63/kg fat corrected milk. Ammonia is down 55%” - Padraig Walsh, Farm Zero C project manager“We are growing multispecies over four years now and we still don’t have enough information to answer if they are doing enough for us – we’ll leave that to Curtins Farm. On red clover we have one field that hasn’t got bag N in four years and we get four cuts per year but another not so good that needed 100kg of nitrogen/ha this year. Cows were scanned and not in-calf cows sold within 48 hours to reduce stocking rate” – Kevin Ahern, farm manager“The cows on multispecies do a lot more urinating, that’s for sure – you’d see it in the parlour. So perhaps they are spreading nitrogen more often in the field” – Kevin Ahern, farm managerUsing clover and multispecies to reduce nitrogen.Chemically amending slurry with GasAbate from GlasPortBio.Feeding methane additive (Bovaer) during housing.17% of grazing area in multispecies.63% of farm has over 20% clover in sward.Performance

16 litres (4.95% fat and 4.03% protein or 1.4 kg MS/cow).Feed 2kg of meal plus grazing.7.6% of cows scanned empty and 16% of heifers (contract reared).Grass grown to date: nine tonnes and hoping to hit 11.5 tonnes for the year (901kg AFC and 330/LU).

Multispecies and clover have been growing on the Shinagh Farm for the last four years but, like all farms, it was slow to get going this year.

The Shinagh Farm is owned indirectly by the four west Cork dairy co-ops. The farm started in 2011 as a demonstration farm pre-quota removal similar to the Greenfield Farm in Kilkenny that started in 2009. Kevin Ahern is farm manager and has been since the start of the project. Over the last number of years, the farm has evolved into more research rather than demonstration, seeking and trialling solutions for decarbonising Irish dairy farming.

The learning

curve continues

There was a written comment on the first board – “the carbon footprint reduction from the project has not negatively impacted farm performance.”

That’s a big statement when just above that you have the fact the farm has grown nine tonnes per hectare to date and purchased 54 acres of silage for winter feed.

Of course, 2024 was a difficult year for all farms, but there are signs that the lower nitrogen is already leading to higher concentrate feeding and more forage purchases. This is despite the fact that the farm has dropped stocking rate.

It is great to have long-term commercial farm studies like this. It allows for real medium- to long-term results to be established replicating what happens on most Irish farms. If we look back over the last 10 years of Shinagh, I believe we can see a real difference emerging between the old-fashioned dairy management compared to the fancy, new lower nitrogen blueprint.

From 2013 to 2017 inclusive, the Shinagh Farm averaged close to 15 tonnes of dry matter grown, meal input was relatively low averaging less than 500kg of meal per cow, and artificial nitrogen input was in the region of 200kg/ha to 250kg/ha.

From 2018, the nitrogen input has started to be reduced, more clover and multispecies were coming into the grazing mix and red clover was been introduced on silage ground.

The perceived environmental measures might well be moving in the right direction, but the unbalanced stool means it’s an uncomfortable seat for farmers

The net effect in terms of feed stocks is that silage for winter feed had to be purchased in at least three of the years, meal fed per cow is closer to 1,000kg per cow and ‘average’ grass grown is closer to 12 tonnes of dry matter per hectare.

Stocking rate was reduced from the previous 2.9 cows/ha norm closer to 2.5 cows/ha. However, the grass grown is still not able to meet the annual feed demands of the stock.

At the walk and afterwards, I spoke to progressive dairy farmers who have been trying to get more clover into swards, trying red clover and multispecies.

The message was similar – the consistency of delivery in this low nitrogen world is not there yet and the risk of a feed deficit during grazing or a deficit of winter feed is much higher.

All were clearly in favour of improving the environmental credentials and have been working hard in this space. However, they said if the three legs of the stool are economic, social and environmental, they are finding problems with the stress (social) of the new system and the economic reality.

Over 11 organisations collaborate in this project co-led by Carbery and BiOrbic.

The perceived environmental measures might well be moving in the right direction, but the unbalanced stool means it’s an uncomfortable seat for farmers. Perhaps the very difficult 2024 grass year is impacting opinions, but I was clearly left with the message that year after year, these farmers are finding the system much more difficult to manage.

In reality, these farms are adjusting to a 25% reduction in feed grown on farm.

The 85 hectares just outside Bandon were producing 1,275 tonnes of feed per year and now it’s closer to 1,000 tonnes of feed.

Yes, the purchased nitrogen input to produce the 1,000 tonnes is less, but with that there is a lot more risk.

Maybe two cows per hectare is closer to where they need to be to match growth rates?

The two big areas where the latest gains have been made are reducing fertiliser usage and reducing the feed production number.

SHARING OPTIONS