Last week, the Irish Farmers Journal hosted a major climate conference in Northern Ireland. David Wright reports here. Our keynote speaker was Prof Myles Allen from the University of Oxford. Prof Allen, a world renowned professor of geosystem science, has been credited with first demonstrating the need for net-zero carbon dioxide emissions to stop global warming. He was also the lead author on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) special report on 1.5 degrees.

His message to farmers and policymakers is equally relevant across the island of Ireland: climate policy must be refocused on warming outcomes in line with the Paris agreement. He describes the current focus on carbon dioxide equivalents as “flawed” when calculating the impact of agriculture on global warming.

Change in policy

The need for the change in policy direction stems from the fact that, according to Prof Allen, using CO2 equivalents as a measure of agricultural emissions does not recognise the fact that methane, which accounts for 66% of agricultural emissions, behaves in a totally different way to carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide.

It is a flaw identified in the IPCC’s sixth assessment report last summer. The report clearly drew attention to the ambiguities that result from combining very long-lived climate pollutants such as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide with short-lived pollutants such as methane in aggregated emission targets. Expressing methane emissions as CO2 equivalent emissions was identified to overstate the impact of methane emissions on global warming by a factor of three to four.

Gases should be assessed separately

Meanwhile, as Peter McCann reports in this week's edition, 33 world-leading climate scientists recently published a paper in the prestigious research journal Nature urging policymakers to assess different greenhouse gases separately when setting targets. The experts state that there is a “high level of agreement” on the underlying science of how different greenhouse gases affect global temperature.

Of course, the policy response should not be to ignore the contribution of methane to global warming. It is a potent greenhouse gas with the IPCC report also pointing out that expressing methane emissions as CO2 equivalent emissions understated the effect of new methane emission sources in global warming.

However, recognising methane as a short-lived greenhouse gas means that methane emissions from agriculture do not need to reach net-zero for the industry to have no warming effect on global temperatures.

Asking too much

According to Prof Allen, ignoring the science and committing the sector to a net-zero target for CO2 equivalents, which includes methane, would in effect be asking farmers not only to stop causing any further global warming but also reverse all the warming caused by the sector since 1980 – no other sector is being asked to deliver this.

Prof Allen pointed to the fact that if NI agriculture reduced CO2 and N2O emissions to zero by 2050 and reduced methane emission by 14% over the same period, it would be enough to stop the sector causing any global warming after 2035. For context, the transport sector is being asked to stop causing global warming by 2050.

To effect this change in policy direction when calculating agriculture’s contribution to global warming would require a separate target for reducing biogenic methane to be established alongside a net-zero target for aggregate carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide emissions by 2050.

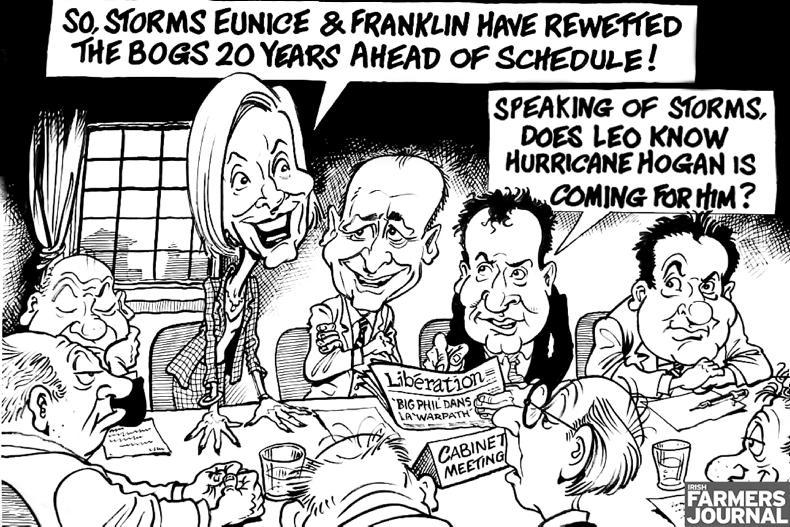

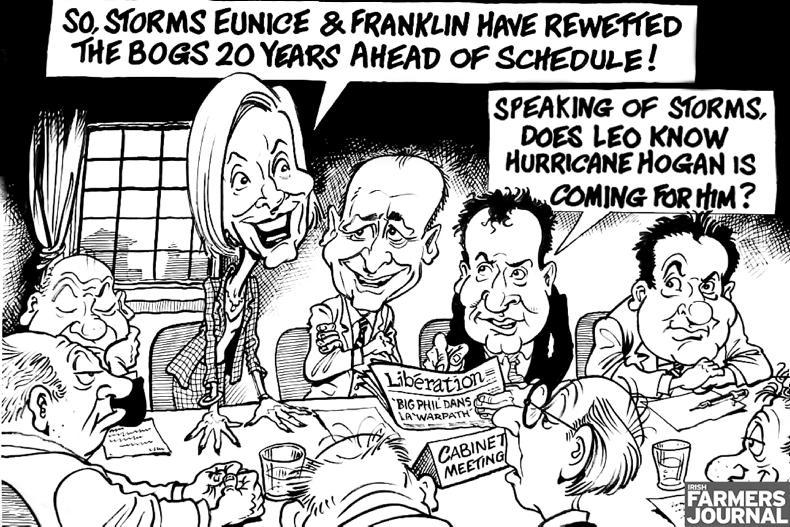

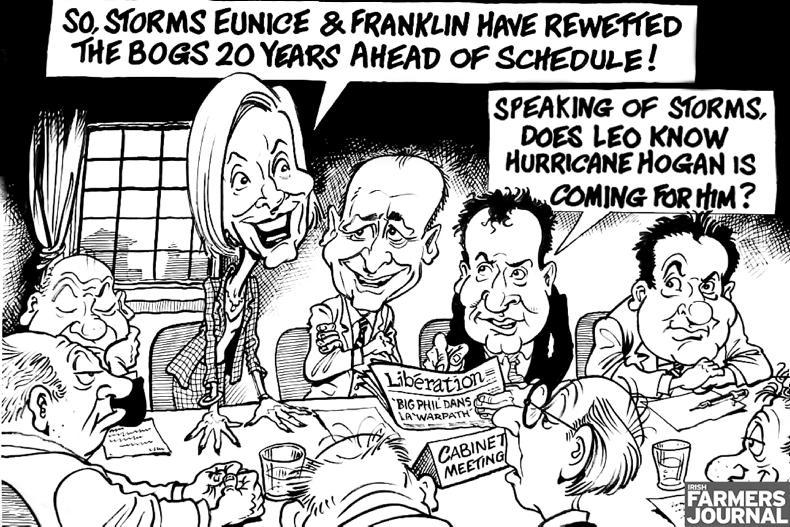

This week's cartoon

/ Jim Cogan

New technologies

Doing so is not a get-out-of-jail card for farmers and would still have significant implications, requiring the rapid uptake of new technologies and changes to farm practice – particularly relating to chemical fertiliser use and the rollout of new methane reduction technologies. But the impact of continuing with the current methodology is becoming ever clearer with the focus nationally turning to stabilising – and then reducing – agricultural emissions to achieve a CO2 equivalent emission reduction target within the range of 22-30% by 2030. The KPMG report points to the fact that based on the capacity of market-ready technologies, the upper end of this range cannot be achieved without a significant reduction in the national cattle herd.

The question is: would establishing a separate target for biogenic methane, alongside an aggressive target to reduce CO2 and N2O emissions, ultimately deliver more to limit global warming, maintain the viability of farmers and, in line with the Paris agreement, protect food security?

Government commitment

There is certainly enough evidence to trigger a detailed modelling exercise and for a policy review by Government to be initiated. It is worth referencing that within the Programme for Government, there is a commitment to recognise the distinct characteristics of biogenic methane in achieving emission reduction targets. However, there may still be challenges ahead. Prof Allen suggests that the reason some policymakers prefer to ignore the science-backed arguments around methane is because they think it easier to reduce cattle and sheep numbers than ask the owner of a closed power station to take their carbon back out of the atmosphere.

Nevertheless, as we go to press it is positive to see policy in Northern Ireland evolving alongside our understanding of the science, with Sinn Féin amendments to the NI Executive’s climate bill recognising the limitations of CO2 equivalents.

Last week, the Irish Farmers Journal hosted a major climate conference in Northern Ireland. David Wright reports here. Our keynote speaker was Prof Myles Allen from the University of Oxford. Prof Allen, a world renowned professor of geosystem science, has been credited with first demonstrating the need for net-zero carbon dioxide emissions to stop global warming. He was also the lead author on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) special report on 1.5 degrees.

His message to farmers and policymakers is equally relevant across the island of Ireland: climate policy must be refocused on warming outcomes in line with the Paris agreement. He describes the current focus on carbon dioxide equivalents as “flawed” when calculating the impact of agriculture on global warming.

Change in policy

The need for the change in policy direction stems from the fact that, according to Prof Allen, using CO2 equivalents as a measure of agricultural emissions does not recognise the fact that methane, which accounts for 66% of agricultural emissions, behaves in a totally different way to carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide.

It is a flaw identified in the IPCC’s sixth assessment report last summer. The report clearly drew attention to the ambiguities that result from combining very long-lived climate pollutants such as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide with short-lived pollutants such as methane in aggregated emission targets. Expressing methane emissions as CO2 equivalent emissions was identified to overstate the impact of methane emissions on global warming by a factor of three to four.

Gases should be assessed separately

Meanwhile, as Peter McCann reports in this week's edition, 33 world-leading climate scientists recently published a paper in the prestigious research journal Nature urging policymakers to assess different greenhouse gases separately when setting targets. The experts state that there is a “high level of agreement” on the underlying science of how different greenhouse gases affect global temperature.

Of course, the policy response should not be to ignore the contribution of methane to global warming. It is a potent greenhouse gas with the IPCC report also pointing out that expressing methane emissions as CO2 equivalent emissions understated the effect of new methane emission sources in global warming.

However, recognising methane as a short-lived greenhouse gas means that methane emissions from agriculture do not need to reach net-zero for the industry to have no warming effect on global temperatures.

Asking too much

According to Prof Allen, ignoring the science and committing the sector to a net-zero target for CO2 equivalents, which includes methane, would in effect be asking farmers not only to stop causing any further global warming but also reverse all the warming caused by the sector since 1980 – no other sector is being asked to deliver this.

Prof Allen pointed to the fact that if NI agriculture reduced CO2 and N2O emissions to zero by 2050 and reduced methane emission by 14% over the same period, it would be enough to stop the sector causing any global warming after 2035. For context, the transport sector is being asked to stop causing global warming by 2050.

To effect this change in policy direction when calculating agriculture’s contribution to global warming would require a separate target for reducing biogenic methane to be established alongside a net-zero target for aggregate carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide emissions by 2050.

This week's cartoon

/ Jim Cogan

New technologies

Doing so is not a get-out-of-jail card for farmers and would still have significant implications, requiring the rapid uptake of new technologies and changes to farm practice – particularly relating to chemical fertiliser use and the rollout of new methane reduction technologies. But the impact of continuing with the current methodology is becoming ever clearer with the focus nationally turning to stabilising – and then reducing – agricultural emissions to achieve a CO2 equivalent emission reduction target within the range of 22-30% by 2030. The KPMG report points to the fact that based on the capacity of market-ready technologies, the upper end of this range cannot be achieved without a significant reduction in the national cattle herd.

The question is: would establishing a separate target for biogenic methane, alongside an aggressive target to reduce CO2 and N2O emissions, ultimately deliver more to limit global warming, maintain the viability of farmers and, in line with the Paris agreement, protect food security?

Government commitment

There is certainly enough evidence to trigger a detailed modelling exercise and for a policy review by Government to be initiated. It is worth referencing that within the Programme for Government, there is a commitment to recognise the distinct characteristics of biogenic methane in achieving emission reduction targets. However, there may still be challenges ahead. Prof Allen suggests that the reason some policymakers prefer to ignore the science-backed arguments around methane is because they think it easier to reduce cattle and sheep numbers than ask the owner of a closed power station to take their carbon back out of the atmosphere.

Nevertheless, as we go to press it is positive to see policy in Northern Ireland evolving alongside our understanding of the science, with Sinn Féin amendments to the NI Executive’s climate bill recognising the limitations of CO2 equivalents.

SHARING OPTIONS