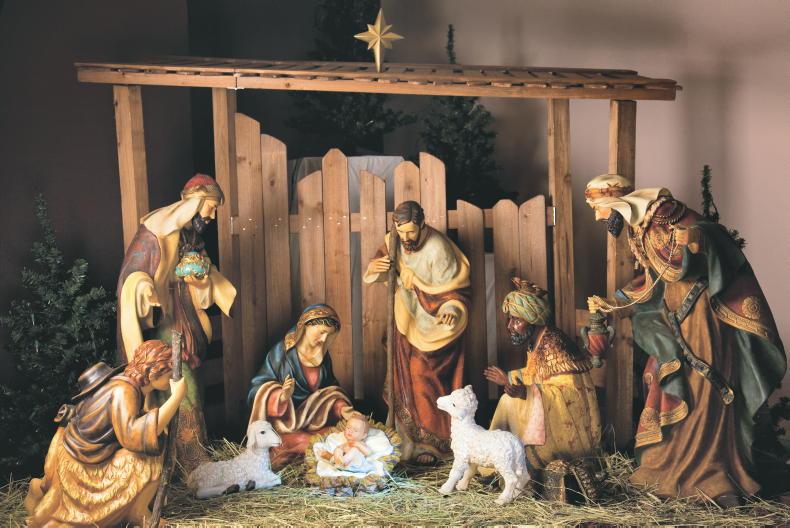

I always felt sorry for the three wise men on their way to the crib. They always seemed to arrive just too late when all the fun and magic of Christmas was over.

As a child, I was a crib aficionado, diligently moving the crowned and turbanned Magi with their gold, frankincense and myrrh along the mantlepiece en route to the straw-lined crib, making sure they got there by the feast of the Epiphany, on 6 January.

After all their trouble, following the star and lugging their expensive gifts, they had no sooner arrived before they were wrapped in sheets of newspaper, packed away and up the ladder with them to the cold attic for another year.

Big Christmas candle

The Adoration of the Magi at Epiphany on 6 January bookended the sacred and magical festive 12 days of Christmas. To mark the Christmas period, the big Christmas candle used to stay burning for the

12 days, corresponding to the 12 months of the year.

If it went out on any day, it was an omen that a death or some calamitous event would take place in that month. If such sinister prognostications were not enough, there was also an established ritual of Twelve Candle Night.

Children were dispatched to pull a clump of plump fat rushes from the rain-saturated fields. Long strips of the rush’s outer hard shell were peeled to reveal their soft spongy pith while one narrow strip of green was left to provide stability. The dry absorbent pith of each rush was dipped in melted tallow or lard and left to dry.

Ashes were then taken from the hearth and mixed with some cow dung to make a cake that was set on a board. Twelve rush lights, each representing the 12 apostles, were lit and set into the soft cake, each family member carefully noting which one they put in place. It was a solemn enough occasion as they knelt to say the rosary, all the while keeping a close eye on their individual rush.

Whoever’s rush burnt out first would be the first to die while those whose burnt the longest would live the longest. When all the rushes burned down, the cake of dung and ashes used to be put up into the rafters of the cowhouse for good luck.

Twelve rushlights were set burning on 'Twelve Candle Night' to mark the end of the Christmas rituals.

This night was known as Nollaig Bheag ‘Little Christmas’ or Nollaig na mBan ‘The Women’s Christmas’ when the women who had toiled, cooking and baking and looking after all the festive chores over the 12 days took a well-deserved break for themselves.

Sometimes ‘Women’s Little Christmas’ has been mischievously re-conflated to ‘Little Women’s Christmas’ but such a jibe does little to quell the enthusiasm of those set on enjoying themselves. In the past, the bulk of the plum pudding was often held back, or some made a small pudding especially for the night.

This along with all manner of baked dainties, slices of fruit cake, pastries and iced biscuits became the fare of the women’s day of celebration. Grannies, sisters, aunts and neighbours would congregate. Over cups of tea or a few glasses of punch or madeira sherry, a night of unbridled fun unfolded.

On 6 January the day of Christ’s first miracle when he changed water into wine at the marriage feast at Cana, is also celebrated.

There was a widely held belief that at midnight the water from the well used to turn to wine, but it was considered very bad luck to go the well at that time and it was customary to bring in an extra bucket of water from the well the evening before.

Frightening accounts

There is the account of the young girl who was sent to the well for water around midnight one Little Christmas Eve when a ‘gamble night’ of a gang playing the card game, 110, was in full flight. When she came back with the bucket the water had turned to wine, red and intoxicating, and the card-players invigorated by the magical intoxicant immediately sent her out for more.

Off she went into the dark night but never returned. In the morning, they found her lying dead beside the well, white as stone and her bucket beside her full of blood.

Such frightening accounts were told, designed to encourage everyone to stay home safe in their beds and to put a stop to their wild abandon and the carnivalesque intemperance and frolic of the 12 days of Christmas.

I always felt sorry for the three wise men on their way to the crib. They always seemed to arrive just too late when all the fun and magic of Christmas was over.

As a child, I was a crib aficionado, diligently moving the crowned and turbanned Magi with their gold, frankincense and myrrh along the mantlepiece en route to the straw-lined crib, making sure they got there by the feast of the Epiphany, on 6 January.

After all their trouble, following the star and lugging their expensive gifts, they had no sooner arrived before they were wrapped in sheets of newspaper, packed away and up the ladder with them to the cold attic for another year.

Big Christmas candle

The Adoration of the Magi at Epiphany on 6 January bookended the sacred and magical festive 12 days of Christmas. To mark the Christmas period, the big Christmas candle used to stay burning for the

12 days, corresponding to the 12 months of the year.

If it went out on any day, it was an omen that a death or some calamitous event would take place in that month. If such sinister prognostications were not enough, there was also an established ritual of Twelve Candle Night.

Children were dispatched to pull a clump of plump fat rushes from the rain-saturated fields. Long strips of the rush’s outer hard shell were peeled to reveal their soft spongy pith while one narrow strip of green was left to provide stability. The dry absorbent pith of each rush was dipped in melted tallow or lard and left to dry.

Ashes were then taken from the hearth and mixed with some cow dung to make a cake that was set on a board. Twelve rush lights, each representing the 12 apostles, were lit and set into the soft cake, each family member carefully noting which one they put in place. It was a solemn enough occasion as they knelt to say the rosary, all the while keeping a close eye on their individual rush.

Whoever’s rush burnt out first would be the first to die while those whose burnt the longest would live the longest. When all the rushes burned down, the cake of dung and ashes used to be put up into the rafters of the cowhouse for good luck.

Twelve rushlights were set burning on 'Twelve Candle Night' to mark the end of the Christmas rituals.

This night was known as Nollaig Bheag ‘Little Christmas’ or Nollaig na mBan ‘The Women’s Christmas’ when the women who had toiled, cooking and baking and looking after all the festive chores over the 12 days took a well-deserved break for themselves.

Sometimes ‘Women’s Little Christmas’ has been mischievously re-conflated to ‘Little Women’s Christmas’ but such a jibe does little to quell the enthusiasm of those set on enjoying themselves. In the past, the bulk of the plum pudding was often held back, or some made a small pudding especially for the night.

This along with all manner of baked dainties, slices of fruit cake, pastries and iced biscuits became the fare of the women’s day of celebration. Grannies, sisters, aunts and neighbours would congregate. Over cups of tea or a few glasses of punch or madeira sherry, a night of unbridled fun unfolded.

On 6 January the day of Christ’s first miracle when he changed water into wine at the marriage feast at Cana, is also celebrated.

There was a widely held belief that at midnight the water from the well used to turn to wine, but it was considered very bad luck to go the well at that time and it was customary to bring in an extra bucket of water from the well the evening before.

Frightening accounts

There is the account of the young girl who was sent to the well for water around midnight one Little Christmas Eve when a ‘gamble night’ of a gang playing the card game, 110, was in full flight. When she came back with the bucket the water had turned to wine, red and intoxicating, and the card-players invigorated by the magical intoxicant immediately sent her out for more.

Off she went into the dark night but never returned. In the morning, they found her lying dead beside the well, white as stone and her bucket beside her full of blood.

Such frightening accounts were told, designed to encourage everyone to stay home safe in their beds and to put a stop to their wild abandon and the carnivalesque intemperance and frolic of the 12 days of Christmas.

SHARING OPTIONS