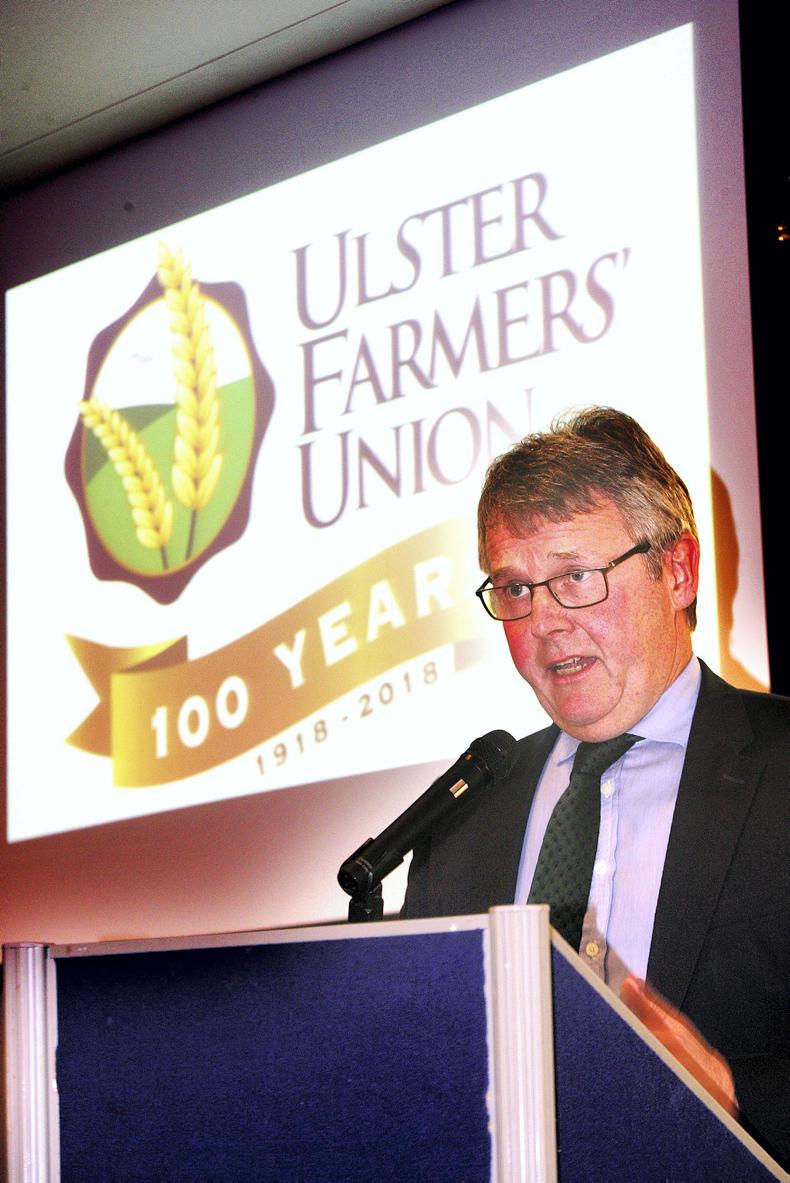

With Defra Secretary of State Michael Gove outlining last week how post-Brexit agricultural policy in England will be aimed at delivering environmental goods, Ulster Farmers’ Union (UFU) president Barclay Bell has warned that food production cannot be left out of future farm support in NI.

“The main thrust of any future agricultural policy must be sustainable food production. We are farmers, not park keepers. We cannot have an imbalance in the support equation away from food production in favour of the environment,” Bell said at the first UFU roadshow event in Enniskillen on Monday evening.

The first in the annual series of UFU roadshow meetings being held this month took place in Co Fermanagh.

The theme of the six roadshows being held across NI this month is “farming and the environment” and the UFU has invited representatives from environmental lobby groups to speak to its members about their views on future agricultural policy.

That probably is a recognition, in part, that these groups are in an increasingly strong lobbying position, especially when set against the backdrop of the promise from Michael Gove for a “green Brexit”. But while there are some competing interests, there is also some significant common ground.

“Farmers need to be profitable, otherwise environmental aspirations go out the window,” commented Barclay Bell.

It was a point reiterated by both RSPB NI director Joanne Sherwood and Ulster Wildlife Trust chief executive Jennifer Fulton. “We need farmers to stay on the land. We do not want land abandonment,” Sherwood said.

Both made the point that marginal land, in particular, needs to be actively farmed to keep it in good environmental condition, and as an important habitat for wildlife.

Listen to an interview with Jennifer Fulton in our podcast below:

Public goods

In his speech at the Oxford Farming Conference last week, Defra Secretary Michael Gove said that future support would be based around “public money for public goods”. A focus of the discussion in Enniskillen was on what actually constitutes a “public good”.

The definition given by Jennifer Fulton was that a “public good is a service or commodity that is provided, without profit, to all members of society”. Examples were given of clean water and air, storage of carbon in soils and trees, and management of protected habitats.

Fulton suggested that food alone is not a public good as it is produced for profit, and under World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, agricultural policy can be challenged if it is seen by another country as unfairly subsidising food production.

However, she said that the process of farming and food production delivers public goods through environmental management. “You provide more than just food as a farmer, you provide multiple benefits to society and, if you can provide more of those, that will help underpin your role and your payments,” Fulton said.

Profit

But that still leaves a question mark over whether farmers will be expected to deliver these public goods within the same framework that currently governs the Environmental Farming Scheme (EFS), where payments only cover costs incurred and income foregone. Without a clear financial incentive, uptake of the wider level EFS has been below target.

In response, Fulton suggested that government money paid for public goods that ends up as farm business profit will not be acceptable to tax payers, although she acknowledged that there will need to be some level of additional incentivisation to encourage farmer uptake.

“Ulster Wildlife are not lobbying for all of the money (existing CAP funds) to go into providing environmental goods. We recognise that there needs to be a viable industry,” she added.

Devolved

Although future agricultural policy in NI will come under a broad UK framework, Barclay Bell reminded UFU members that policy will be a devolved matter for NI.

“We don’t have a Northern Ireland executive at present, but hopefully we will by 2022. I think we can come up with an agricultural policy that is suitable for here,” the UFU president said.

Tax reform opportunities with Brexit

Aside from significant changes to agricultural policy, Jeremy Moody from the Central Association of Agricultural Valuers (CAAV) told UFU members on Monday that Brexit also presents an opportunity to reform taxes relevant to farming in the UK.

The main change that CAAV is pressing for is income tax breaks for landowners who lease land in longer-term tenancy agreements. This is to encourage landowners away from short-term conacre arrangements, with similar tax breaks proving successful in the Republic of Ireland. “Conacre is insecure and does not allow investment in the land,” Moody said.

He said template tenancy agreements are available from CAAV, and agreements can be designed specifically for the landowner and farmer’s needs. He also highlighted that land in a longer-term lease is eligible for the same agricultural property relief (APR) from inheritance tax as conacre.

Treasury study

On the particular issue of APR, Moody said it was not something CAAV are lobbying government to change.

“A recent research study by the Treasury on APR came back with a clean bill of health. It said people are using it because they want to protect their family assets and avoid farms being split up at death. It is not being used, as it is sometimes reported, by people to shield themselves from inheritance tax by buying up farmland,” Moody said.

Farmers need practical regulations

While future Government policy seems to be focused on farmers delivering more environmental goods, there is also the raft of regulation already in place, and the threat of tighter rules to come.

“We cannot be strangled with environmental regulation which could fossilise the industry. We accept regulation, regulation is here to stay, but it must be proportionate, and it must be practical,” UFU president Barclay Bell told members at the meeting in Enniskillen.

His point was reinforced by deputy president Ivor Ferguson, who said that farmers had been treated unfairly by the NI Environment Agency (NIEA) on the issue of ammonia emissions.

He maintained that farmers have been given no recognition for steps already taken to reduce emissions, such as a 1% reduction in crude protein levels in rations which have led to a 10% reduction in ammonia. Also, hot water heating in broiler houses, which has reduced emissions by 40%.

On the current closed period for spreading slurry, the message from the UFU leadership team is that farmers must aim to stay within the rules.

“The arrangements that we have in current time might be as good as it gets. This year, farmers have shown that they can be responsible if they are up against it and allowed to use the reasonable excuse clause,” commented Barclay Bell.

UFU lays down red line on TB

The UFU will not agree to proceed with any other measures from the ongoing DAERA consultation on TB eradication until issues with the TB reservoir in wildlife are addressed. “Until we see meaningful intervention with wildlife, we cannot proceed with anything else,” UFU president Barclay Bell told members in Enniskillen.

The most contentious of the DAERA proposals for farmers include paying for a TB herd test each year and a cap on compensation for reactor animals. Despite being heavily critical of these measures, deputy president Victor Chestnutt did acknowledge that concessions will have to be made eventually. “We cannot say no, no, no the whole way. We will have to accept a bit of pain at some point,” he said.

When asked about the credibility of the skin test in tackling TB, UFU policy officer Geoff Thompson pointed out that the test eradicated TB in Australia and reduced incidence rates from 9% to 3% in the Republic of Ireland. “The skin test is a good enough test provided it is supported with the right policy measures,” he said.

SHARING OPTIONS