LOYALTY CODE:

The paper code cannot be redeemed when browsing in private/incognito mode. Please go to a normal browser window and enter the code there

LOYALTY CODE:

The paper code cannot be redeemed when browsing in private/incognito mode. Please go to a normal browser window and enter the code there

This content is copyright protected!

However, if you would like to share the information in this article, you may use the headline, summary and link below:

Title: Market for forestry land flourishes

Regarded as a solid investment, the growing interest from investors in securing forests and land suitable for afforestation has generated a thriving market for marginal land across the country.

https://www.farmersjournal.ie/market-for-forestry-land-flourishes-255514

ENTER YOUR LOYALTY CODE:

The reader loyalty code gives you full access to the site from when you enter it until the following Wednesday at 9pm. Find your unique code on the back page of Irish Country Living every week.

CODE ACCEPTED

You have full access to farmersjournal.ie on this browser until 9pm next Wednesday. Thank you for buying the paper and using the code.

CODE NOT VALID

Please try again or contact us.

For assistance, call 01 4199525

or email subs@farmersjournal.ie

Sign in

Incorrect details

Please try again or reset password

If would like to speak to a member of

our team, please call us on 01-4199525

Reset

password

Please enter your email address and we

will send you a link to reset your password

If would like to speak to a member of

our team, please call us on 01-4199525

Link sent to

your email

address

![]()

We have sent an email to your address.

Please click on the link in this email to reset

your password. If you can't find it in your inbox,

please check your spam folder. If you can't

find the email, please call us on 01-4199525.

![]()

Email address

not recognised

There is no subscription associated with this email

address. To read our subscriber-only content.

please subscribe or use the reader loyalty code.

If would like to speak to a member of

our team, please call us on 01-4199525

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

Update Success !

Investor interest in forestry has fluctuated widely in Ireland over the past four decades since the advent of the first State-aided forestry programme in the mid 1980s. Sales of forests and suitable land for afforestation have been small and as a result forest valuation has relied on expectation rather than transaction value until relatively recently.

The initial afforestation programmes created a climate for private investment but this decreased in the 1990s, mainly because premiums for private investors were less than a fifth of farm forestry rates when annual payments and their time scale (20 years for farmers and 12 years for private investors) were included.

In addition, the State, which had a large-scale afforestation programme for most of the 20th century, ceased land purchase by the mid 1990s. Coillte reduced its annual afforestation programme from 7,855ha in 1991 to 317ha in 2001 mainly because the company failed to qualify for annual premium payments.

As Coillte and private investment contracted, so too did the sale of bare land suitable for afforestation. Essentially, forestry development became almost exclusively a farm enterprise as private investors failed to make an economic case for forestry when land purchase, negligible premiums and the time scale of the investment were factored in.

“Farmers accounted for 83% of private lands afforested between 1980 and 2015,” maintains the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine report Ireland’s Forests – Annual Statistics 2015.

However, investors are returning to forestry and there has been a gradual increase in sales of forests to the private sector since 2010. This has further increased since 2015 due to the following two developments:

The removal of the differentiation between farmer and non-farmer premium payments “has seen the participation of non-farmers increase to 15% of the area afforested in 2015, which is the highest level since 1995,” maintains the department report.

Other factors make forestry an attractive proposition for investors. For example, commercial woodlands are exempt from capital gains tax on the growing timber.

Return on investment

While these are attractive incentives, the decision to invest in forestry is ultimately determined by the rate of return on investment. Forestry companies such as Green Belt Ltd and Forestry Services Ltd (FSL) estimate an annual rate of return on investment of 5-7% and 5-10% respectively, while the Government strategic forestry plan Growing for the Future estimates 4%. “Forestry investment is recognised as a relatively low-risk investment which provides a competitive return,” maintains Paddy Bruton, managing director of FSL.

The FSL return is based on planting bare land, but Green Belt maintains that the returns are better for investors wishing to purchase semi-mature plantations. A 20-year-old plantation would provide “at least 6% per annum compounded”, Green Belt maintains, while the Irish Forest Unit Trust (IForUT) estimates an annual return of between 6.1% and 7.4%. Brendan Lacy, chief executive IForUT regards forestry as “a valuable low-risk core holding in protecting pension fund value and returns”.

Timber prices have been traditionally strong in Ireland as sawmills pay considerably more than their UK counterparts for logs. Long-term market forecasts for timber are positive, especially in Ireland where there is overcapacity in the timber processing industry and likely to be increased demand in the wood energy market.

While Ireland will continue to rely on the UK as a major export market, wood, unlike food, has few fears in a post-Brexit marketplace. Trade tariffs are expected to be zero between EU and non-EU countries which is the case currently in the sawn timber market.

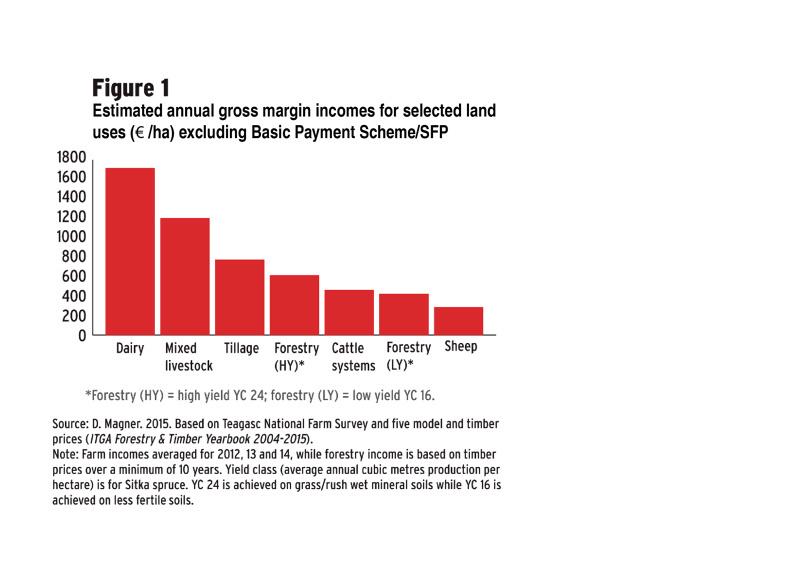

Farmers who invest in forestry are more likely to be influenced by its performance in comparison with other land uses. While income from forestry falls well short of dairy and mixed livestock farming on better-quality land, it performs extremely well when compared with cattle and sheep systems, especially in high yield class (YC) forests (see Figure 1).

The Teagasc National Farm Survey shows that income from YC 24 (m3/ha/annum) forests provide 41% greater revenue than predominantly suckler farm production and 24% higher than systems where cattle fattening is the dominant enterprise.

Income from lower-yield forests – averaging YC16 – is 3% below suckler cattle systems and 14% below predominantly cattle-fattening systems. High-yielding forests provide an annual income of €602, up to 57% higher than sheep farming.

The term forestry land refers to:

Sale of bare land: Forestry companies, auctioneers and estate agents contacted by the Irish Farmers Journal report increased activity in bare land sale. Paul Lafferty, the forestry specialist with James Cleary & Sons, Castlerea, said there has been a marked increase in queries “for sites suitable for planting, in particular wet grass rush land”. His clients include farmers, professional people and investment companies who see forestry as providing a better return than banks or government bonds.

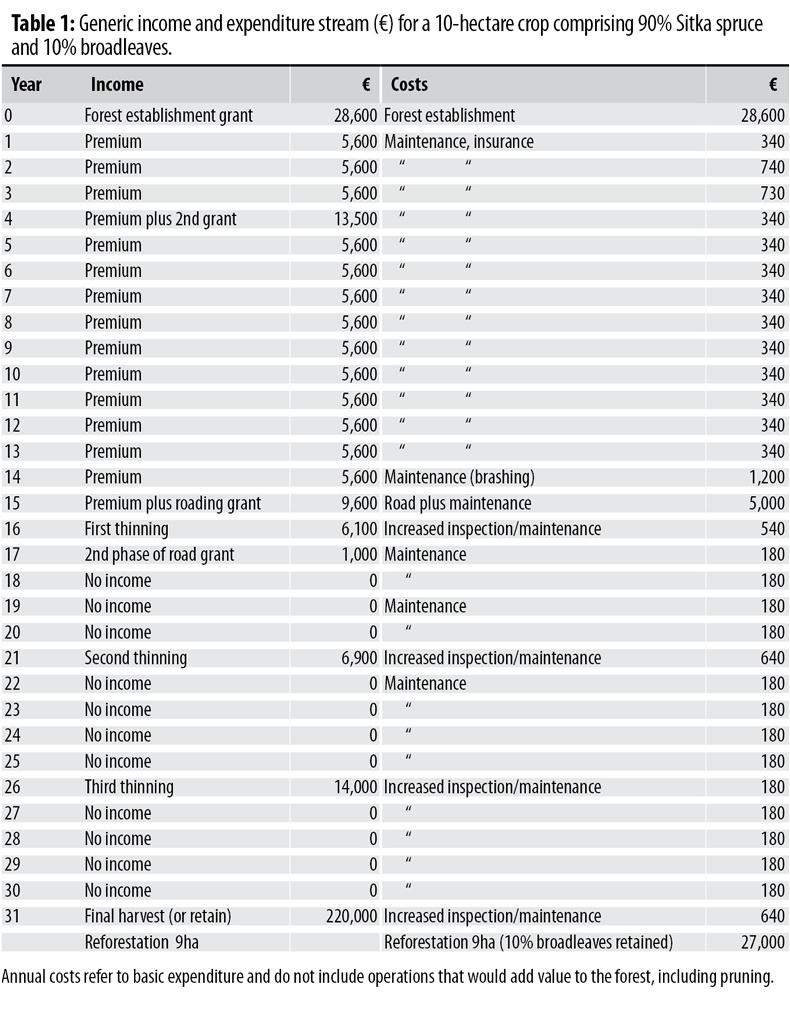

“We have forestry land on our books throughout Ireland, unsuitable for agriculture but capable of producing high yielding forests, which is selling for up to €5,000 an acre (€12,000/ha),” he said. “Banks look favourably on loan applications for forestry due to the 100% grant for establishing a forest and the 15-year tax-free premiums which will bring the forest to the production phase,” according to Paddy Bruton. The continuous income stream from forestry (Table 1) is a deciding factor in banks providing loans. “Forestry is now a liquid asset which is easier to trade and both private investors and farmers see it as a safe, solid and secure investment.”

Sale of forests: The number of forest sales has also increased in Ireland although transactions are still small in number. As a result, comprehensive information on forest valuation is difficult to determine. However, Paddy Bruton and Paul Lafferty agree that a picture is emerging from increased sales that prices are now based on transaction, rather than expected value.

“Investors now factor in yield, timber prices, rotation lengths, location and other information in reaching a scientific forest valuation,” said Paddy Bruton. “We find that they are only interested in high-yielding well-stocked quality crops, usually with spruce or other saleable conifers,” he said. “However, we also have clients who are interested in slow-growing broadleaved forests provided the quality is good.”

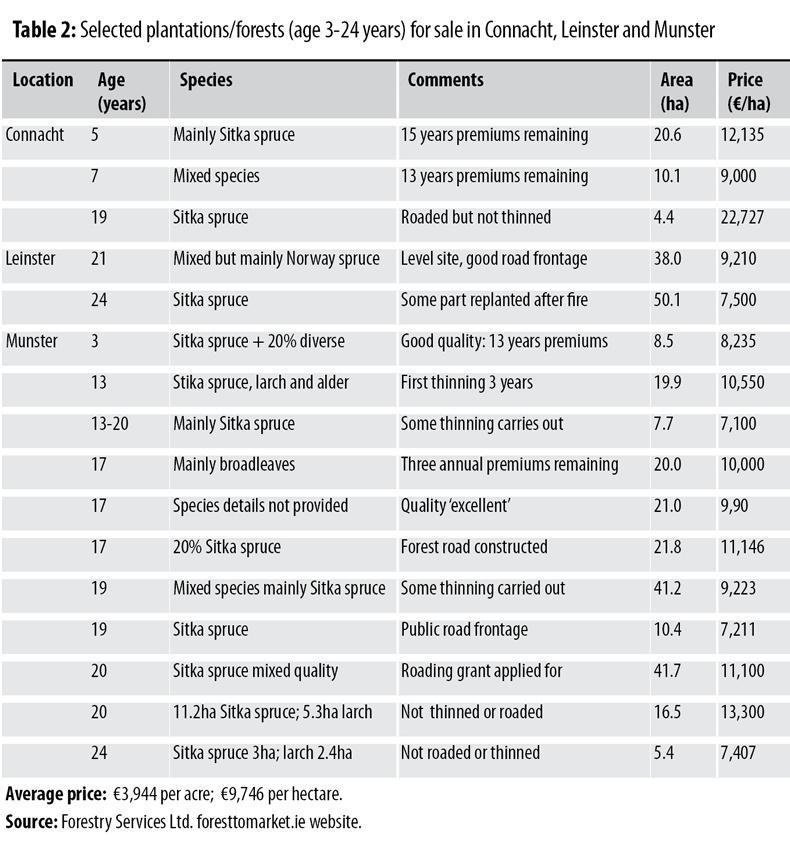

In 2016, FSL launched the website foresttomarket.ie, which is a dedicated platform for investors to source existing forests and land suitable for forestry for sale by auctioneers in Ireland. The small cross section of sites (Table 2) provides a snapshot of expected prices for lots in Connaught, Leinster and Munster.

These sites varied from recently established plantations to 24-year-old forests. The average price reserve is €9,746/ha (€3,944/ac). This is close to forest land prices provided in the 2016 study The Irish Forestry Land Market carried out by the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland (SCSI).

The study reported that the average price paid for forests in 2015 was €9,838/ha, which was marginally higher than 2011, when €9,697/ha was achieved but well up on the €7,991/ha average for 2012.

Future prospects

Further investment by the private sector is likely over the coming years. This is evidenced in the recent interest by investment and pension funds in forestry. The arrival of the pan-European investment fund Dasos is likely to stimulate forest sales throughout Ireland. The fund plans to invest in 18,000ha of forests using an €83.5m fund comprising €55m from the Ireland Strategic Investment Fund (ISIF) and €28.5m from the European Investment Bank (EIB).

The Dasos arrival has received a mixed reception. Pat Collins, chair of the IFA farm forestry group, maintains that funding should be provided for farmers and producer groups to support and grow an indigenous forestry sector. Padraig Egan, general manager of SWS Forestry, one of the companies sourcing forests for Dasos Capital in Ireland, believes the Finnish fund management company “will provide a welcome boost to the semi-mature forestry land market”.

“While the vast majority of private forest owners in Ireland are farmers, there is growing demand for forestry land from other non-farmer individuals and institutions (private equity funds),” according to the Land Market Review and Outlook 2016, compiled by Teagasc and the Society of Chartered Surveyors. The review notes that “demand is especially strong from mature investors and high net worth individuals that already have knowledge/understanding of the forestry sector and are looking to diversify their existing investment portfolio with long-term pension planning in mind”.

Despite major interest from private investors, farmers are best positioned to maximise the return from forestry. The obvious advantage is that farmers don’t have to purchase forestry land which is likely to increase in value.

Current prices of €12,000/ha (€4,800/ac) and over for good-quality forestry land are high but given an average annual income of €600/ha, it still represents a good investment in comparison to good agricultural land valued between €25,000 to €30,000/ha (circa €10,000 to €12,000/ac).

SHARING OPTIONS: