Foaling in the mare is typically a rapid event, with an average time of only 20 minutes from the rupture of the membranes (waters breaking) to the foal being delivered. Every 10 minutes of a delay beyond 30 minutes has been reported to reduce foal survival by 10%. With that in mind, here are a few points to keep in mind if assisting with a foaling.

During late pregnancy the foal lies upside down in the mare’s uterus, with its spine facing the mare’s belly. Foaling is well underway before the foal rolls over, faces the mare’s tail and straightens out its front legs, ready to be born.

The mare typically gets uneasy, walks, paws, and sweats up during stage one of labour. As it progresses, she may get down and roll. These movements help the foal turn over, so the mare should be left alone as much as possible, unless she seems to be in a lot of pain or abruptly stops showing any signs of progressing. Knowing the mare’s typical behaviour during previous births is extremely helpful, so detailed foaling records are always valuable – and make sure they are readily accessible in the middle of the night.

Recording the time

It is really important to try and make a note of exactly what time the waters break at, as all subsequent events should be monitored from this point. It’s so easy to spend 15-30 valuable minutes trying to correct a malpositioned foal, when that time would be much better spent getting expert help, or dispatching the mare to an equine hospital for an assisted delivery under general anaesthesia.

Stages of foaling

Stage one: Uterine contractions begin, foal turnsover,this stage ends when the waters break.

Stage two: The passage of thefoal through the birth canal to deliver it.

Stage three: Expulsion of the afterbirth (‘cleaning’).

Typical timing of key events

Amnionic (white) membrane appears at the vulva: 10 minutes after waters breaking.

Foal’s feet appear at the vulva: 15 minutes after waters breaking.

Birth of the foal: 20 minutes after waters breaking.

Passing of the afterbirth: Within two hours of foaling.

Hygiene

A clean, short-sleeved and ideally waterproof foaling gown or top should be worn. Thoroughly wash and dry your hands and forearms. A rectal glove will protect the mare’s tract – wearing a short disposable glove on top of the rectal sleeve can help to keep the sleeve in place and make it easier to feel what is going on. Apply some obstetrical gel to the back of your hand and arm for lubrication.

When handling the mare, make as few in-and-out movements with your arm through the birth canal as possible, to reduce the risk of tissue damage, bleeding and tears. Take care to avoid dragging any tail hairs with you, as they can cause irritation and introduce bacteria.

Foal position

Once the waters have broken, the foal’s position in the birth canal can be checked. A tail wrap will help keep long hairs and dirt safely out of the way. Pass a hand into the mare’s vulva and locate the feet – run your fingers along them to feel the knees (carpal joint) to confirm that they are indeed a pair of front feet. One foot should be in front of the other to help the shoulders fit through the pelvis. The foal’s head usually rests on its forearms with the nose slightly to one side. If everything is in place let the mare go again, as she may get up and down a few more times before finally lying down to push strongly and deliver her foal.

Complications

If a problem develops during a foaling call your vet straight away. Delays are never helpful and even if the foal happens to arrive before the vet, it is still important to have both the mare and foal checked over. Treatment may be needed to minimise the impact of a slow or complicated delivery.

Foot over the head

This is a relatively common cause of foaling injuries. To avoid a hoof tearing the mare’s vagina and rectum, the foal needs to be pushed back into the uterus. Get the mare up if possible: an assistant can encourage her to stand or walk in circles to reduce her tendency to strain as the foal is pushed back.

Repelling the foal into the uterus should allow enough space for the feet to be correctly repositioned under the head. Then ‘walk’ the shoulders through the pelvis by pulling on one foot at a time and alternating them. Pull the foal’s feet towards the mare’s hocks as it is delivered, as this facilitates the natural direction of travel of the shoulders and hips through the pelvis.

Standing delivery

Young and/or anxious mares may refuse to lie down to foal. Assistance is likely to be needed to help deliver the foal against the pull of gravity. If possible, catch the foal as it is born and lower it to the ground to reduce the risk of injury. A newborn foal is heavy, floppy and extremely slippery, so having two or more attendants is really helpful in this case.

Failure to push

A sick, injured or exhausted mare may be simply unable to push. A tear in the diaphragm (the sheet of muscle dividing the chest from the abdomen) is another rare cause – the mare needs to be able to hold her breath and contract her abdominal muscles to create the necessary force.

Any mare that is unable to generate regular, forceful muscle contractions once the foal’s front feet and head enter the birth canal is likely to need an assisted delivery.

Stuck at the hips

Given that the shoulders are the widest part of the foal, getting stuck at the hips is rare in horses. If it does occur, it is typically due to the foal’s stifles getting caught on the pelvis. It needs to be corrected quickly, as the umbilical cord may be caught and crushed between the foal’s abdomen and the pelvis, depriving the foal of oxygen.

Sometimes just changing the direction of a pull on the front limbs is enough to free the foal. If not, you need to try and rotate the hips. Grasp the foal around the body behind its ribs and try to twist its hips while lifting the torso off the ground. This is difficult and requires strength. If this fails you can grasp the foal firmly by the front leg, closest to the ground. Use both hands and pull the foal’s foot directly upwards, towards the ceiling. The aim is to help one stifle pop up over the pelvis. Pulling the front foot is easier than twisting the foal’s hips, but it risks damage to the ribs.

There is on average only 20 minutes from waters breaking to the birth of the foal.

Things to avoid:

• Any delay in seeking assistance if things appear to be going wrong.

• More than two adults pulling on the foal’s limbs at once.

• Continuous, unrelenting traction – try and work with the mare: pull when she strains and release the tension to just hold the foal where it is between efforts.

• Using a calving jack (as the mare’s reproductive tract is much more prone to damage than is the case for cattle).

• Spending more than five minutes trying to unsuccessfully correct a malpositioned foal if any other option to successfully manage the case exists.

• It is strongly recommended that a discussion is held between the mare owner, the vet and the foaling attendants (if applicable) well before the expected foaling date. This allows a plan to be made to manage any emergencies should they arise, and greatly reduces the risk of a complication turning into a complete disaster.

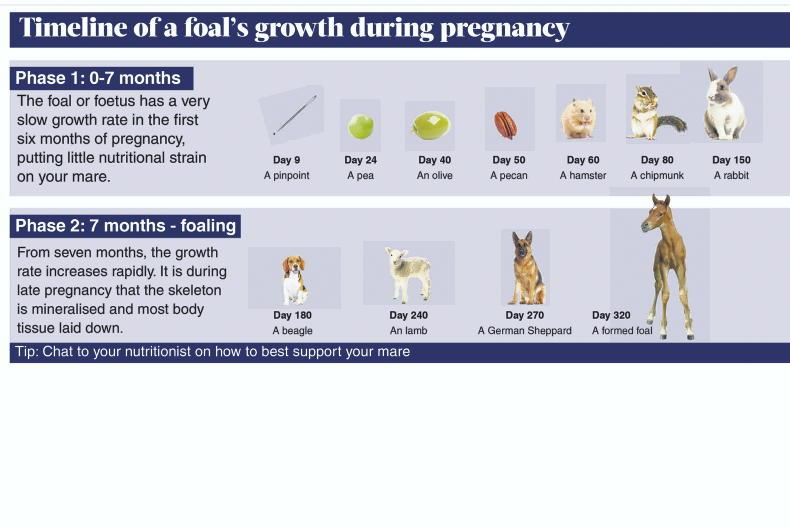

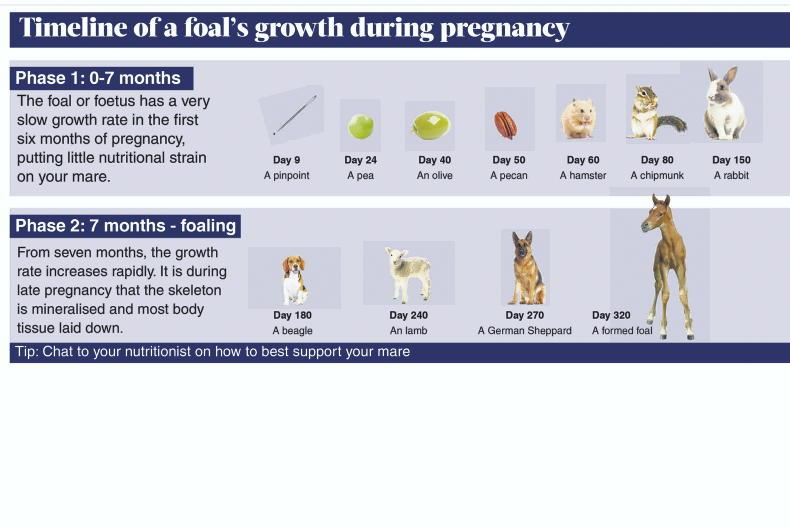

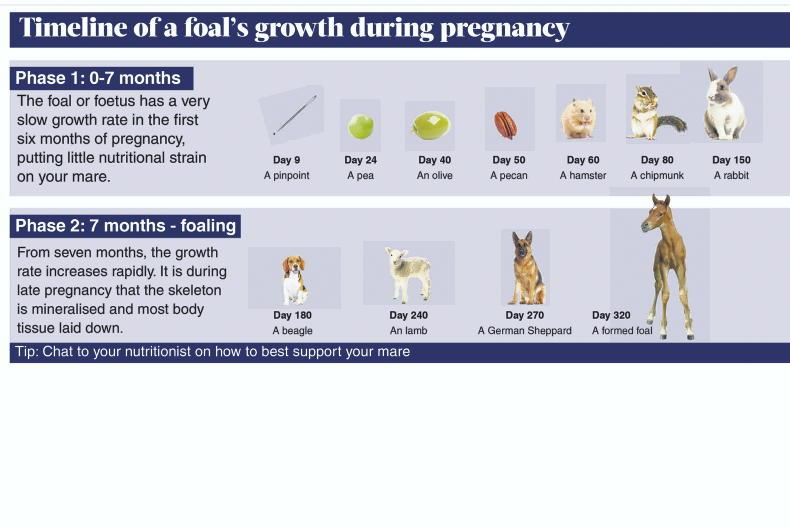

Timeline chart.

Foaling in the mare is typically a rapid event, with an average time of only 20 minutes from the rupture of the membranes (waters breaking) to the foal being delivered. Every 10 minutes of a delay beyond 30 minutes has been reported to reduce foal survival by 10%. With that in mind, here are a few points to keep in mind if assisting with a foaling.

During late pregnancy the foal lies upside down in the mare’s uterus, with its spine facing the mare’s belly. Foaling is well underway before the foal rolls over, faces the mare’s tail and straightens out its front legs, ready to be born.

The mare typically gets uneasy, walks, paws, and sweats up during stage one of labour. As it progresses, she may get down and roll. These movements help the foal turn over, so the mare should be left alone as much as possible, unless she seems to be in a lot of pain or abruptly stops showing any signs of progressing. Knowing the mare’s typical behaviour during previous births is extremely helpful, so detailed foaling records are always valuable – and make sure they are readily accessible in the middle of the night.

Recording the time

It is really important to try and make a note of exactly what time the waters break at, as all subsequent events should be monitored from this point. It’s so easy to spend 15-30 valuable minutes trying to correct a malpositioned foal, when that time would be much better spent getting expert help, or dispatching the mare to an equine hospital for an assisted delivery under general anaesthesia.

Stages of foaling

Stage one: Uterine contractions begin, foal turnsover,this stage ends when the waters break.

Stage two: The passage of thefoal through the birth canal to deliver it.

Stage three: Expulsion of the afterbirth (‘cleaning’).

Typical timing of key events

Amnionic (white) membrane appears at the vulva: 10 minutes after waters breaking.

Foal’s feet appear at the vulva: 15 minutes after waters breaking.

Birth of the foal: 20 minutes after waters breaking.

Passing of the afterbirth: Within two hours of foaling.

Hygiene

A clean, short-sleeved and ideally waterproof foaling gown or top should be worn. Thoroughly wash and dry your hands and forearms. A rectal glove will protect the mare’s tract – wearing a short disposable glove on top of the rectal sleeve can help to keep the sleeve in place and make it easier to feel what is going on. Apply some obstetrical gel to the back of your hand and arm for lubrication.

When handling the mare, make as few in-and-out movements with your arm through the birth canal as possible, to reduce the risk of tissue damage, bleeding and tears. Take care to avoid dragging any tail hairs with you, as they can cause irritation and introduce bacteria.

Foal position

Once the waters have broken, the foal’s position in the birth canal can be checked. A tail wrap will help keep long hairs and dirt safely out of the way. Pass a hand into the mare’s vulva and locate the feet – run your fingers along them to feel the knees (carpal joint) to confirm that they are indeed a pair of front feet. One foot should be in front of the other to help the shoulders fit through the pelvis. The foal’s head usually rests on its forearms with the nose slightly to one side. If everything is in place let the mare go again, as she may get up and down a few more times before finally lying down to push strongly and deliver her foal.

Complications

If a problem develops during a foaling call your vet straight away. Delays are never helpful and even if the foal happens to arrive before the vet, it is still important to have both the mare and foal checked over. Treatment may be needed to minimise the impact of a slow or complicated delivery.

Foot over the head

This is a relatively common cause of foaling injuries. To avoid a hoof tearing the mare’s vagina and rectum, the foal needs to be pushed back into the uterus. Get the mare up if possible: an assistant can encourage her to stand or walk in circles to reduce her tendency to strain as the foal is pushed back.

Repelling the foal into the uterus should allow enough space for the feet to be correctly repositioned under the head. Then ‘walk’ the shoulders through the pelvis by pulling on one foot at a time and alternating them. Pull the foal’s feet towards the mare’s hocks as it is delivered, as this facilitates the natural direction of travel of the shoulders and hips through the pelvis.

Standing delivery

Young and/or anxious mares may refuse to lie down to foal. Assistance is likely to be needed to help deliver the foal against the pull of gravity. If possible, catch the foal as it is born and lower it to the ground to reduce the risk of injury. A newborn foal is heavy, floppy and extremely slippery, so having two or more attendants is really helpful in this case.

Failure to push

A sick, injured or exhausted mare may be simply unable to push. A tear in the diaphragm (the sheet of muscle dividing the chest from the abdomen) is another rare cause – the mare needs to be able to hold her breath and contract her abdominal muscles to create the necessary force.

Any mare that is unable to generate regular, forceful muscle contractions once the foal’s front feet and head enter the birth canal is likely to need an assisted delivery.

Stuck at the hips

Given that the shoulders are the widest part of the foal, getting stuck at the hips is rare in horses. If it does occur, it is typically due to the foal’s stifles getting caught on the pelvis. It needs to be corrected quickly, as the umbilical cord may be caught and crushed between the foal’s abdomen and the pelvis, depriving the foal of oxygen.

Sometimes just changing the direction of a pull on the front limbs is enough to free the foal. If not, you need to try and rotate the hips. Grasp the foal around the body behind its ribs and try to twist its hips while lifting the torso off the ground. This is difficult and requires strength. If this fails you can grasp the foal firmly by the front leg, closest to the ground. Use both hands and pull the foal’s foot directly upwards, towards the ceiling. The aim is to help one stifle pop up over the pelvis. Pulling the front foot is easier than twisting the foal’s hips, but it risks damage to the ribs.

There is on average only 20 minutes from waters breaking to the birth of the foal.

Things to avoid:

• Any delay in seeking assistance if things appear to be going wrong.

• More than two adults pulling on the foal’s limbs at once.

• Continuous, unrelenting traction – try and work with the mare: pull when she strains and release the tension to just hold the foal where it is between efforts.

• Using a calving jack (as the mare’s reproductive tract is much more prone to damage than is the case for cattle).

• Spending more than five minutes trying to unsuccessfully correct a malpositioned foal if any other option to successfully manage the case exists.

• It is strongly recommended that a discussion is held between the mare owner, the vet and the foaling attendants (if applicable) well before the expected foaling date. This allows a plan to be made to manage any emergencies should they arise, and greatly reduces the risk of a complication turning into a complete disaster.

Timeline chart.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: