As the temperatures increase, we are once more heading into the worm season on farms. Stomach and gut worms, as well as lungworms, need warmth and moisture to complete their lifecycles and over the summer period this can take as little as three to four weeks.

A small worm burden can become a large problem leading to scour and ill-thrift within weeks when environmental conditions are good.

While it is tempting to just treat animals on a regular basis or as often as possible to get rid of any worms, over the longer term, this can bring other issues such as resistance to wormers.

Cattle also need to be exposed to a small number of worms to develop a natural immunity but not so many as to become clinically ill from the worm infection, which is a difficult balance to strike.

With blanket treatments using long-acting wormers that prevent any exposure, the calves do not have the opportunity to develop this immunity and may remain at high risk into their second grazing season.

Monitoring animals with faecal egg counts is one way to try to determine the best times to treat in the season. If there are no worm eggs in the dung, treatments can possibly be delayed by a few weeks.

Usually, there are much fewer eggs on pastures early in the season and worm treatment is not needed until a number of weeks into the warmer season.

If there are scour problems in calves early at grazing, coccidia parasites may also be a cause and a dung sample can help to distinguish this from a worm problem, as they require different treatments.

While stomach and gut worm burdens predictably increase over the grazing season, lungworm outbreaks remain unpredictable.

Faecal eggs counts are also not helpful for detecting lungworm outbreaks.

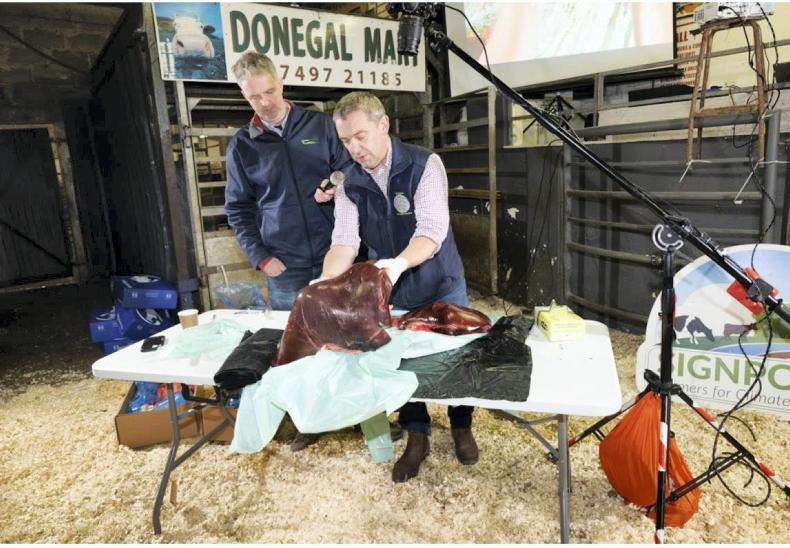

The TASAH aims to facilitate parasite control planning tailored to your farm. \ Philip Doyle

Animals should rather be closely monitored, particularly first-season grazers, for any signs of coughing and the group treated as soon as possible if lungworm is suspected.

Rather than dosing often, what else can be done to prevent worm problems?

Risk management

Parasite control is based on risk management and one of the most effective ways to manage the worm burden on the farm is with pasture management.

Evaluate which pastures are likely to have the heaviest contamination of worm eggs and larvae. For example, pastures that have been grazed by calves in the previous season, particularly in autumn, are likely to be more heavily contaminated.

These pastures should then be avoided for grazing by the animals most at risk of developing clinical signs – first-season grazing calves, specifically spring-born dairy calves and autumn-born dairy and beef calves.

Suckler calves that are unweaned and with their dams are at much lower risk and usually don’t need dosing until the autumn when their grass uptake increases.

Grazing adult animals or mixed-species grazing can help reduce the contamination of pasture after calves have grazed. Adults have usually developed immunity to stomach and gut worms and sheep are not affected by many of the cattle gut worms. It is rare for adult cattle to show any clinical signs of stomach or gut worms, although lungworm can still be a concern if they are exposed to very contaminated pastures or have not developed a good immunity to lungworm.

Make parasite planning part of the herd health plan

A comprehensive parasite control plan can help to prevent production losses due to worms before obvious clinical signs are seen. Controlling parasites is a complex problem.

It requires planning and evaluating the risks tailored to a farm.

There is a parasite control targeted advisory service on animal health (TASAH) available

A parasite control plan should consider parasite factors, weather, testing, grazing and farm management and should be adapted as the weather changes, for example, in very dry summers.

There is a parasite control targeted advisory service on animal health (TASAH) available, which funds a free veterinary visit on parasite control to address some of these difficulties. This fully funded service is voluntary and open to all cattle and sheep farmers in Ireland.

The TASAH includes two faecal egg counts to test the number of worm eggs in a dung sample and the efficacy of any treatments given.

TASAH consult

A newly developed parasite control targeted advisory service on animal health (TASAH) is available for 2022. This voluntary programme can assist farmers by funding a free veterinary farm visit and two faecal egg counts and is open to all cattle and sheep farms in Ireland.

Farmers must register and nominate their trained vet to participate. The programme aims to facilitate parasite control planning tailored to the farm and slow the development of anthelmintic resistance.

More information on the programme and how to register is available on the AHI website or by contacting your vet.

Monitor any stock bulls for lameness, ill health or infertility, so that performance is not affected.Use heat detection systems and top up tail paint to catch the remaining cycling cows.Summer mastitis – focus on dry cow therapy and fly control to prevent problems, particularly for autumn-calving cows.Blowfly strike in sheep – minimise soiling through good worm control and managing fleeces and wounds, along with fly treatments. Start monitoring for stomach and gut worms with faecal egg counts to optimise the timing of wormer treatments. With animals back on pasture, it is important to effectively clean the sheds to prevent a buildup of infection for the next season – note that if there were coccidiosis problems, a disinfectant that is active against coccidial oocysts is needed.Redwater fever can still be a problem in cattle at this time of year. Seek treatment quickly for animals with fever, diarrhoea, dark red urine or weakness, especially if there is a history of the disease on farm.

As the temperatures increase, we are once more heading into the worm season on farms. Stomach and gut worms, as well as lungworms, need warmth and moisture to complete their lifecycles and over the summer period this can take as little as three to four weeks.

A small worm burden can become a large problem leading to scour and ill-thrift within weeks when environmental conditions are good.

While it is tempting to just treat animals on a regular basis or as often as possible to get rid of any worms, over the longer term, this can bring other issues such as resistance to wormers.

Cattle also need to be exposed to a small number of worms to develop a natural immunity but not so many as to become clinically ill from the worm infection, which is a difficult balance to strike.

With blanket treatments using long-acting wormers that prevent any exposure, the calves do not have the opportunity to develop this immunity and may remain at high risk into their second grazing season.

Monitoring animals with faecal egg counts is one way to try to determine the best times to treat in the season. If there are no worm eggs in the dung, treatments can possibly be delayed by a few weeks.

Usually, there are much fewer eggs on pastures early in the season and worm treatment is not needed until a number of weeks into the warmer season.

If there are scour problems in calves early at grazing, coccidia parasites may also be a cause and a dung sample can help to distinguish this from a worm problem, as they require different treatments.

While stomach and gut worm burdens predictably increase over the grazing season, lungworm outbreaks remain unpredictable.

Faecal eggs counts are also not helpful for detecting lungworm outbreaks.

The TASAH aims to facilitate parasite control planning tailored to your farm. \ Philip Doyle

Animals should rather be closely monitored, particularly first-season grazers, for any signs of coughing and the group treated as soon as possible if lungworm is suspected.

Rather than dosing often, what else can be done to prevent worm problems?

Risk management

Parasite control is based on risk management and one of the most effective ways to manage the worm burden on the farm is with pasture management.

Evaluate which pastures are likely to have the heaviest contamination of worm eggs and larvae. For example, pastures that have been grazed by calves in the previous season, particularly in autumn, are likely to be more heavily contaminated.

These pastures should then be avoided for grazing by the animals most at risk of developing clinical signs – first-season grazing calves, specifically spring-born dairy calves and autumn-born dairy and beef calves.

Suckler calves that are unweaned and with their dams are at much lower risk and usually don’t need dosing until the autumn when their grass uptake increases.

Grazing adult animals or mixed-species grazing can help reduce the contamination of pasture after calves have grazed. Adults have usually developed immunity to stomach and gut worms and sheep are not affected by many of the cattle gut worms. It is rare for adult cattle to show any clinical signs of stomach or gut worms, although lungworm can still be a concern if they are exposed to very contaminated pastures or have not developed a good immunity to lungworm.

Make parasite planning part of the herd health plan

A comprehensive parasite control plan can help to prevent production losses due to worms before obvious clinical signs are seen. Controlling parasites is a complex problem.

It requires planning and evaluating the risks tailored to a farm.

There is a parasite control targeted advisory service on animal health (TASAH) available

A parasite control plan should consider parasite factors, weather, testing, grazing and farm management and should be adapted as the weather changes, for example, in very dry summers.

There is a parasite control targeted advisory service on animal health (TASAH) available, which funds a free veterinary visit on parasite control to address some of these difficulties. This fully funded service is voluntary and open to all cattle and sheep farmers in Ireland.

The TASAH includes two faecal egg counts to test the number of worm eggs in a dung sample and the efficacy of any treatments given.

TASAH consult

A newly developed parasite control targeted advisory service on animal health (TASAH) is available for 2022. This voluntary programme can assist farmers by funding a free veterinary farm visit and two faecal egg counts and is open to all cattle and sheep farms in Ireland.

Farmers must register and nominate their trained vet to participate. The programme aims to facilitate parasite control planning tailored to the farm and slow the development of anthelmintic resistance.

More information on the programme and how to register is available on the AHI website or by contacting your vet.

Monitor any stock bulls for lameness, ill health or infertility, so that performance is not affected.Use heat detection systems and top up tail paint to catch the remaining cycling cows.Summer mastitis – focus on dry cow therapy and fly control to prevent problems, particularly for autumn-calving cows.Blowfly strike in sheep – minimise soiling through good worm control and managing fleeces and wounds, along with fly treatments. Start monitoring for stomach and gut worms with faecal egg counts to optimise the timing of wormer treatments. With animals back on pasture, it is important to effectively clean the sheds to prevent a buildup of infection for the next season – note that if there were coccidiosis problems, a disinfectant that is active against coccidial oocysts is needed.Redwater fever can still be a problem in cattle at this time of year. Seek treatment quickly for animals with fever, diarrhoea, dark red urine or weakness, especially if there is a history of the disease on farm.

SHARING OPTIONS