LOYALTY CODE:

The paper code cannot be redeemed when browsing in private/incognito mode. Please go to a normal browser window and enter the code there

LOYALTY CODE:

The paper code cannot be redeemed when browsing in private/incognito mode. Please go to a normal browser window and enter the code there

This content is copyright protected!

However, if you would like to share the information in this article, you may use the headline, summary and link below:

Title: 'Every mother wants their child to be remembered. And their grief acknowledged'

When Anne Devine’s son Seán died suddenly at just 18 months old, it was too painful to process. Now 35 years on, she’s reclaiming Seán’s space for herself.

https://www.farmersjournal.ie/every-mother-wants-their-child-to-be-remembered-and-their-grief-acknowledged-785455

ENTER YOUR LOYALTY CODE:

The reader loyalty code gives you full access to the site from when you enter it until the following Wednesday at 9pm. Find your unique code on the back page of Irish Country Living every week.

CODE ACCEPTED

You have full access to farmersjournal.ie on this browser until 9pm next Wednesday. Thank you for buying the paper and using the code.

CODE NOT VALID

Please try again or contact us.

For assistance, call 01 4199525

or email subs@farmersjournal.ie

Sign in

Incorrect details

Please try again or reset password

If would like to speak to a member of

our team, please call us on 01-4199525

Reset

password

Please enter your email address and we

will send you a link to reset your password

If would like to speak to a member of

our team, please call us on 01-4199525

Link sent to

your email

address

![]()

We have sent an email to your address.

Please click on the link in this email to reset

your password. If you can't find it in your inbox,

please check your spam folder. If you can't

find the email, please call us on 01-4199525.

![]()

Email address

not recognised

There is no subscription associated with this email

address. To read our subscriber-only content.

please subscribe or use the reader loyalty code.

If would like to speak to a member of

our team, please call us on 01-4199525

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

Update Success !

On the night of 20 September 1988- like so many nights before – Anne Devine laid her two sons down to sleep.

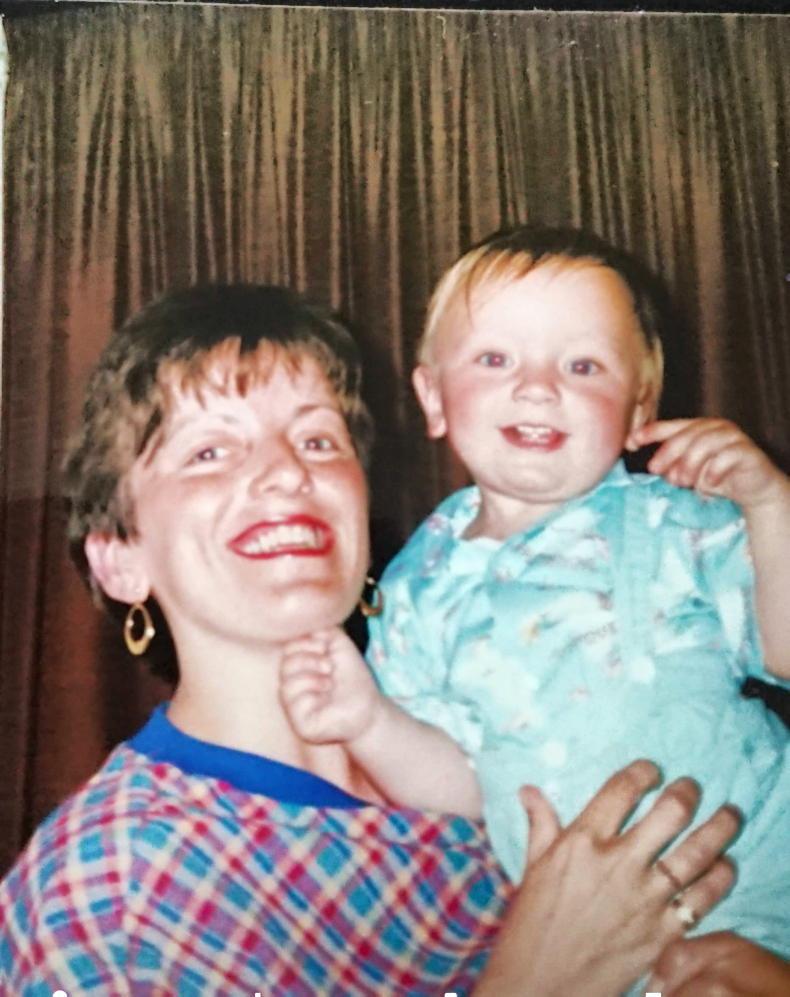

Baby Daniel, just four weeks young, and his blue-eyed, blonde-haired brother, Seán, 18 months old.

“And what I always remember about the night was that I had made a cup of tea,” recalls Anne.

“Do you know the way when you’re a young mum and you think, ‘I’ll grab that moment for me?’ I had made a cup of tea, I laid it up beside the kitchen sink and I thought, ‘I’ll just run upstairs and I’ll check on them’.

“Ran into Daniel’s room, fine. Ran into Seán’s room and I knew instantly, the minute I opened the door, there’s something wrong in the room. There was some stillness. And he had actually died in his cot.”

A blur

Much of what followed is now a blur. Anne remembers calling her husband, Billy; a doctor and a priest arriving; the house filling with loved ones as the awful news travelled.

But?

“What I really remember is, hours later in the kitchen, I picked up my cup of tea and I put my hand on it; and it was still warm. That was the shocking thing to me,” says Anne quietly.

“That my life had changed, utterly, from the time I ran upstairs to the time that I came back down.”

Irish Country Living is speaking to Anne to coincide with Pregnancy and Infant Loss Awareness Day, which falls on 15 October.

The date of our interview, however, is 22 September 2023: 35 years and two days after that night that Anne has just re-lived; and just two days after Seán 35th anniversary. We ask how it feels to be talking about her son in this public sense, given the significance of this week.

She considers the question carefully.

“I think that, speaking myself as a parent, the one thing you do want to do is you want to talk about your child that died, because I think the great fear you have is that nobody will remember him or that he lived,” she responds.

“And I think every mother carries that in their heart, that wanting for them to be remembered. And I couldn’t talk about Seán when he died. It was too painful. And I think I represent a lot of women in the ‘80s.”

Sudden and unexplained

Anne Devine and her husband Billy live on a suckler and sheep farm in the shelter of the Knockmealdowns, close to Lismore, Co Waterford. Anne herself spent most of her career as a teacher and later, principal, of Cappoquin primary school until retiring in 2015.

Reflecting now, she believes that it was this decision that allowed her to revisit- and in turn, reframe- the impact of Seán’s loss, but also, his life, on her own.

Anne was just 27 when her first son was born on 1 March, 1987. She remembers looking at the daffodils out the window, their sunshine faces smiling in welcome for the new arrival.

“I remember a nurse coming in and saying, ‘Oh, it’s the feast of St David!’” recalls Anne.

“And she may have been saying, ‘Are you thinking of David [as his name]?’ and I said, ‘No, he’s Seán. Seán William.’ I just felt he was Seán from the first day, on the first of March.”

Described as “an easy-going child from day one,” Anne says that even strangers would be drawn to peep into Seán’s buggy, such was his sunny nature.

“He had a lovely smile and a really warm personality,” she says. “And seemed to be very happy with simple things.”

The arrival of Seán’s younger brother, Daniel, on 17 August, 1988 brought more joy to the young family; only to be hit by the lightening strike that was Seán’s sudden, unexpected and unexplained death a month later due to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), referred to as cot death at that time.

“It’s best described as you put an apparently healthy baby to bed; and they just die in their sleep,” says Anne so simply, yet so devastatingly. “SIDS is that nature of suddenness.”

Grief fog

Seán passed away on a Tuesday and was buried on a Thursday. Despite the grief fog, Anne does recall particular moments, such as the “strange silence” that descended, almost deafeningly, on the house after the funeral.

“It was like the noise in the house was gone with Seán gone,” she remembers, “and the dinkies [cars] all over the place.”

She also recalls bringing Daniel for his six week check-up; and not being able to even verbalise the horror of what had happened.

“It was that sense of my voice was gone,” she says. “My head was so mixed-up, such was the trauma.”

Looking back now, Anne believes that the only way she survived that period was by a process of disassociation.

She remembers one day, almost a year afterwards, spotting a blonde boy on the beach in Clonea and walking towards him, convinced that it was Seán until the painful truth dawned once again; another time, going into a baby boutique to buy an outfit for him.

“And the lady at the shop said, ‘Is that for your child?’ And I looked at it and I thought, ‘Why am I buying an outfit for a child who is dead?’ It’s like your mind is going back and forth. Are they gone? Are they really gone?” she explains.

“And I ran out of that shop. It takes a long time to realise that they’re not coming back.”

Compounding the situation was the fact that Anne admits that she felt guilty for many years as she was the person who put Seán to bed that night.

“And I couldn’t save him,” she explains, heartbreakingly. “I think that was hard as a mother to feel.”

Societal response

Looking for any answer, Anne did connect with the Irish Sudden Infant Death Association (now FirstLight) and discovered that she was not alone in how she felt.

“I went to ISIDA for answers at the time and the answer is very clear: there really is no warning. And people find it hard to get their heads around it,” she says.

“It can happen to anyone, but from my point of view, the question in the early years was, ‘But why did it have to happen to me?’ And you eventually in time come to terms with that question.”

Anne also sought counselling and was fortunate to have supportive family and friends, but says that the “most common societal response at that time” was to distract or deflect from the grief.

“The prevailing societal thing was, ‘Get on with it, move on with it, don’t think about it too much, aren’t you lucky you have another child,’” she lists.

Whatever little support was there for mothers, however, Anne feels strongly that fathers were certainly forgotten.

“All the men who are out there whose children died, how many people have ever asked them, ‘How are you? How did you feel?’ Because most likely what they were asked is, ‘How is your wife doing?’” says Anne.

“There was a denial for men that they were allowed to feel anything.”

Reclaiming space

Life must – and did – continue. In 1995, Anne and Billy welcomed the arrival of their daughter Kate into the family. Those were busy, enjoyable, child-rearing years- Daniel loving hurling, Kate horses – every year running into the next.

Anne continued to advance in her career; though looking back, she sees that working so hard may have been something of “a crutch.”

“As I was coming up on choosing retirement, I began asking myself the question, ‘What was I really distracting myself from?’” she reflects. “And I probably was distracting myself from facing the reality of Seán’s death and how I had coped with it.”

One of the first things that Anne did in retirement was complete The Artist’s Way: a 12-week course designed as a means to unlock creativity. As part of this process, Anne began to journal daily, which in turn inspired her to write her book “Encourage Yourself, Encourage Others”: a pocket-sized companion imparting life lessons on themes including friendship, resilience, healing and gratitude.

Anne dedicated this book to Seán; but it was while giving talks to groups on the back of the publication that she began to speak about her loss publicly. And she soon found that there were many women who also felt silenced, for so long.

“That’s the way it was back then. And it shouldn’t have been that way,” says Anne, who feels that talking about her son today is almost like “bringing Seán to life”.

“But you’re also helping people of my age to see that it’s ok to talk about a child who died 35 years ago,” she continues. “It’s more than ok. It’s lovely to do so.”

For anybody struggling with the loss of a child- be it recently or decades ago- Anne acknowledges that it does take “courage to ask for help.”

But?

“If you can just be brave enough to say, ‘It’s our son’s anniversary this week, I’m kind of finding myself a bit anxious and a bit lonely around it,’ there will be somebody there who will understand that and will help you through it,” says Anne.

Irish Country Living could talk to Anne for hours; but as we come to the end of the interview, we ask her how she is feeling now, having re-lived the greatest loss in her life. We know it’s not easy.

“I feel like I’m reclaiming a space for Seán,” she responds. “And it’s important to say that the space never went away. It’s just that I’m understanding now the importance of talking about it.”

Yet the truth is that, even if a single word was never uttered again, Seán Devine lives in his mother’s thoughts, in her heart, in her words and in her work: every single day.

“‘Seán lived,’” smiles Anne. “His life mattered.”

Readers can follow Anne on Instagram @encouragementbyanne or by visiting https://www.encouragementbyanne.ie/

SHARING OPTIONS: