A few generations back, the most exciting part of Christmas was invariably the arrival of the mummers and their rollicking play. Mumming can be understood as a variation of rhyming and/or miming and refers to a very old, once-widespread, tradition of localised folk drama.

Throughout the country, merry bands of actors – mummers – dressed in fantastic regalia, went from house to house, entertaining and thrilling the audiences who witnessed their performances.

Each group would have a captain at their head, and he would lead and guide the group around a hinterland, stopping into each house to perform their set of rehearsed rhymes.

In the rural areas, the much-anticipated arrival of the mummers would be announced by the blowing of a horn, which would set all the dogs in the area barking. Later when horns were hard to come by, an old bottle with its bottom knocked out could make the same bellowing sound.

The captain would knock on the door with his staff and ask to gain entry with

his opening rhyme:

Room, room gallant friends,

Give us room to rhyme,

We’ve come to show activity,

At this Christmas time.

The various other characters were then called in, one by one. Most were dressed in the typical straw costume with tall conical hats that preserved their anonymity.

Their different identities were distinguished by a few choice props. A popular character such as the ‘Butcher’ would wear a striped or bloodied apron and carry a small wooden knife.

Beelzebub or ‘Divily Doubt’ would carry a frying pan which was flung about with abandon, much to everyone’s amusement.

Hero-fight play

Two of the mumming characters, St Finbarr and Oliver Cromwell making peace with each other.

The core of the midwinter performance focused on what is known as the hero-fight play. Here, two of the central characters who are sworn enemies, usually Prince George and the Turkish Champion or St Patrick and Oliver Cromwell, began boasting about their various attributes and got on each other’s nerves.

They went at each other with their wooden swords and after a scuffle, one of them was killed.

Oliver Cromwell, distinguished by a big copper nose was the regular character to be killed, but if loyalties were different, it was the saint who met his end.

Their death led to a certain amount of panic, and this was the cue for the entrance of the doctor wearing his distinctive top hat and carrying his medical bag. The doctor could revive the dead hero with a fanciful concoction, the make-up of which was always very comical.

The wit of a weasel, the wool of a frog,

15 ounces of last November’s fog.

The brains of a hatchet,

The juice of a lime burner’s whiskers.

All mixed together and well stirred,

With a hen’s tooth and a cat’s feather.

From a little bottle, the doctor poured the magical liquid into the dead hero’s ear, and he immediately came back to life.

Such a dramatic presentation of a miraculous resurrection may well be the key to understanding the untold focus of the mumming plays which took place around the midwinter turning point of the year.

This is the dormant stasis in the cycle of natural and agricultural fertility and the playing out of death followed by new life is a knowing folk technique in marking and understanding this point of change and the positive increase that is to follow.

Amongst the many characters was the all-important female figure, ‘Biddy Funny’ who carried a broom and a bag.

Her rhyme ran:

Here comes I Little Miss Funny,

With me big long bag to carry the money,

It’s money I want and money I crave,

If you don’t give me money,

I’ll sweep you into the grave,

All silver and no brass,

If you don’t give me money,

I’ll steal your ass!

‘All silver and no brass’ will remind many of the parish priest’s appeal for a ‘silent collection’ at Mass. Any monies collected might be the source of a dance or gathering held on or before the end of the 12 days of Christmas, on 6 January.

Regardless of any monies collected, the function of the mummers was to mark the start of the new cycle of the year and to bestow on everyone that they visited, prosperity and good fortune.

Along with those sentiments, in addition, I would like to wish all our readers continued health and happiness for the year ahead.

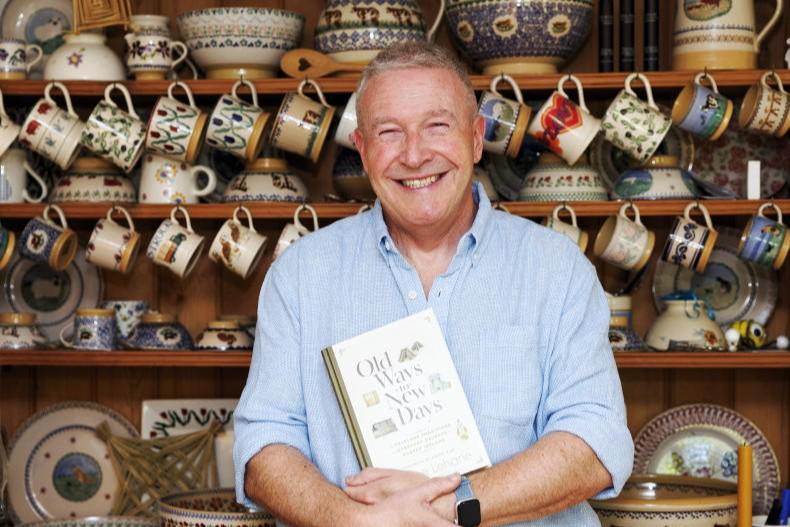

Shane Lehane is a folklorist who works in UCC and Cork College of FET, Tramore Road Campus. Contact: slehane@ucc.ie

A few generations back, the most exciting part of Christmas was invariably the arrival of the mummers and their rollicking play. Mumming can be understood as a variation of rhyming and/or miming and refers to a very old, once-widespread, tradition of localised folk drama.

Throughout the country, merry bands of actors – mummers – dressed in fantastic regalia, went from house to house, entertaining and thrilling the audiences who witnessed their performances.

Each group would have a captain at their head, and he would lead and guide the group around a hinterland, stopping into each house to perform their set of rehearsed rhymes.

In the rural areas, the much-anticipated arrival of the mummers would be announced by the blowing of a horn, which would set all the dogs in the area barking. Later when horns were hard to come by, an old bottle with its bottom knocked out could make the same bellowing sound.

The captain would knock on the door with his staff and ask to gain entry with

his opening rhyme:

Room, room gallant friends,

Give us room to rhyme,

We’ve come to show activity,

At this Christmas time.

The various other characters were then called in, one by one. Most were dressed in the typical straw costume with tall conical hats that preserved their anonymity.

Their different identities were distinguished by a few choice props. A popular character such as the ‘Butcher’ would wear a striped or bloodied apron and carry a small wooden knife.

Beelzebub or ‘Divily Doubt’ would carry a frying pan which was flung about with abandon, much to everyone’s amusement.

Hero-fight play

Two of the mumming characters, St Finbarr and Oliver Cromwell making peace with each other.

The core of the midwinter performance focused on what is known as the hero-fight play. Here, two of the central characters who are sworn enemies, usually Prince George and the Turkish Champion or St Patrick and Oliver Cromwell, began boasting about their various attributes and got on each other’s nerves.

They went at each other with their wooden swords and after a scuffle, one of them was killed.

Oliver Cromwell, distinguished by a big copper nose was the regular character to be killed, but if loyalties were different, it was the saint who met his end.

Their death led to a certain amount of panic, and this was the cue for the entrance of the doctor wearing his distinctive top hat and carrying his medical bag. The doctor could revive the dead hero with a fanciful concoction, the make-up of which was always very comical.

The wit of a weasel, the wool of a frog,

15 ounces of last November’s fog.

The brains of a hatchet,

The juice of a lime burner’s whiskers.

All mixed together and well stirred,

With a hen’s tooth and a cat’s feather.

From a little bottle, the doctor poured the magical liquid into the dead hero’s ear, and he immediately came back to life.

Such a dramatic presentation of a miraculous resurrection may well be the key to understanding the untold focus of the mumming plays which took place around the midwinter turning point of the year.

This is the dormant stasis in the cycle of natural and agricultural fertility and the playing out of death followed by new life is a knowing folk technique in marking and understanding this point of change and the positive increase that is to follow.

Amongst the many characters was the all-important female figure, ‘Biddy Funny’ who carried a broom and a bag.

Her rhyme ran:

Here comes I Little Miss Funny,

With me big long bag to carry the money,

It’s money I want and money I crave,

If you don’t give me money,

I’ll sweep you into the grave,

All silver and no brass,

If you don’t give me money,

I’ll steal your ass!

‘All silver and no brass’ will remind many of the parish priest’s appeal for a ‘silent collection’ at Mass. Any monies collected might be the source of a dance or gathering held on or before the end of the 12 days of Christmas, on 6 January.

Regardless of any monies collected, the function of the mummers was to mark the start of the new cycle of the year and to bestow on everyone that they visited, prosperity and good fortune.

Along with those sentiments, in addition, I would like to wish all our readers continued health and happiness for the year ahead.

Shane Lehane is a folklorist who works in UCC and Cork College of FET, Tramore Road Campus. Contact: slehane@ucc.ie

SHARING OPTIONS