As a child, Ellen Ryan could never “really relate” to the female characters in Irish myths and legends.

Or rather, how they had been re-written.

“Niamh was this temptress who lured Oisín away and that didn’t serve him. Medb was a greedy, cow-snatching villain. Gráinne… she’s just a damsel in distress,” she despairs.

But as the author of Girls Who Slay Monsters: Daring Tales of Ireland’s Forgotten Goddesses” which was recently named Children’s Book of the Year at the An Post Book Awards- Ellen is hoping to change the well-trodden narrative; and empower young readers in the process.

While familiar with traditional tales of Tír na nÓg or The Salmon of Knowledge from school, Ellen explains that it was her grandmother, Carmel Wood, who first introduced her to ancient texts like the Táin. This inspired her in more ways than one.

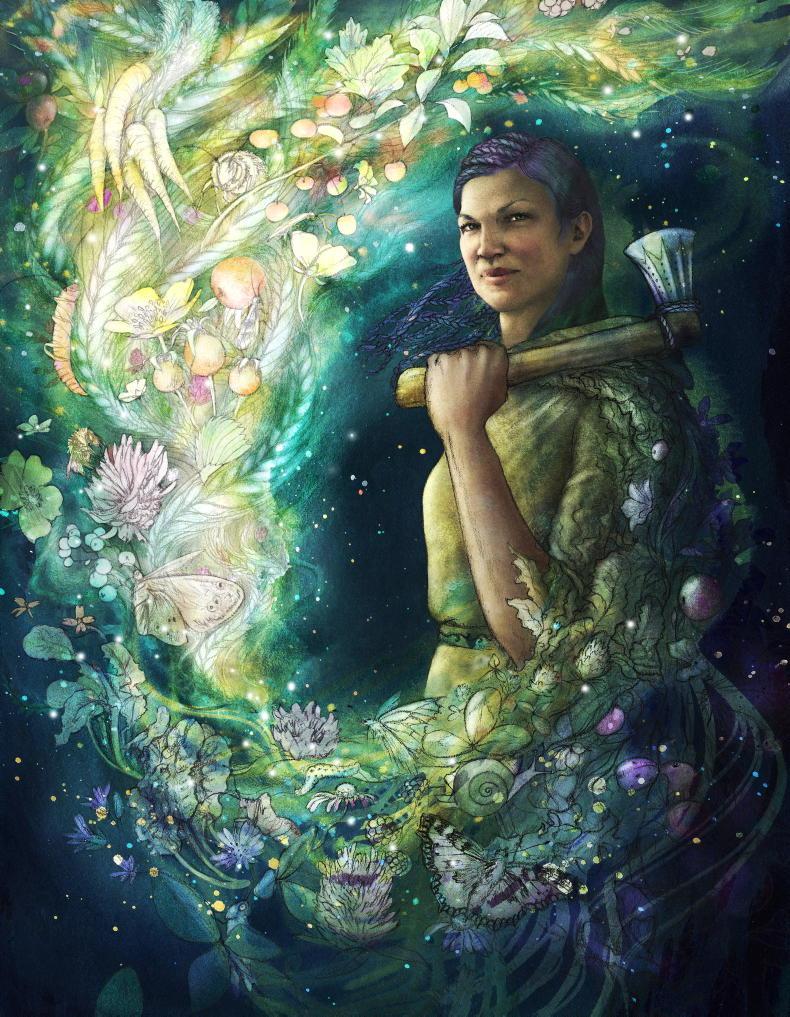

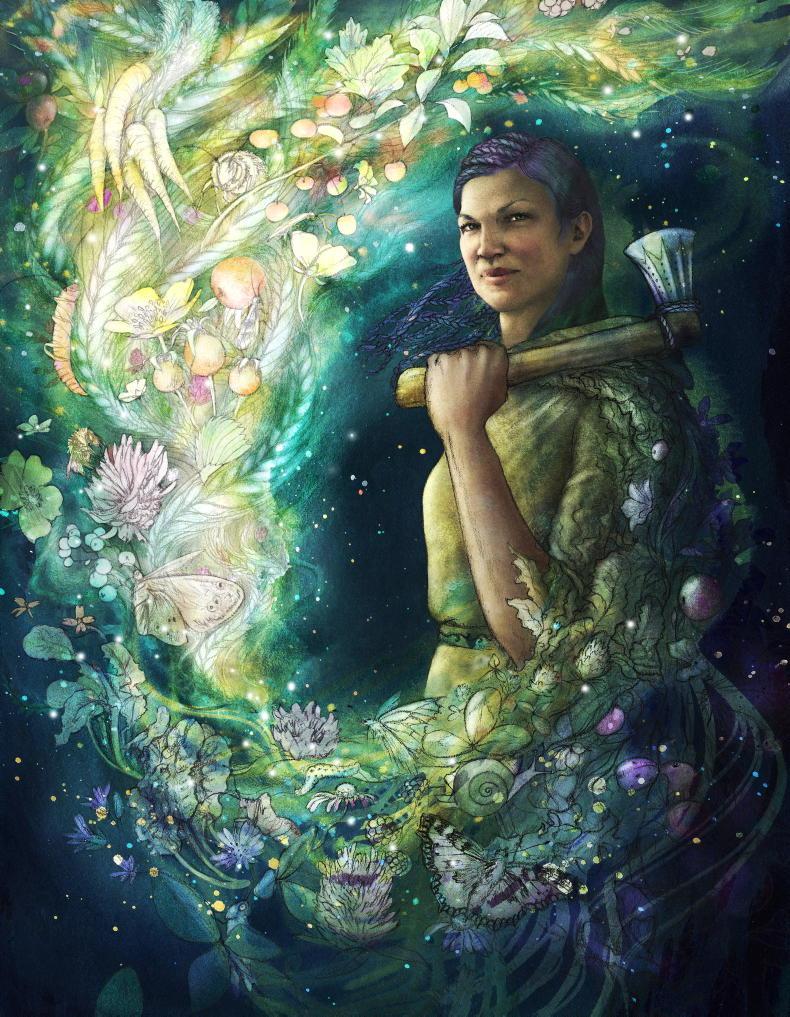

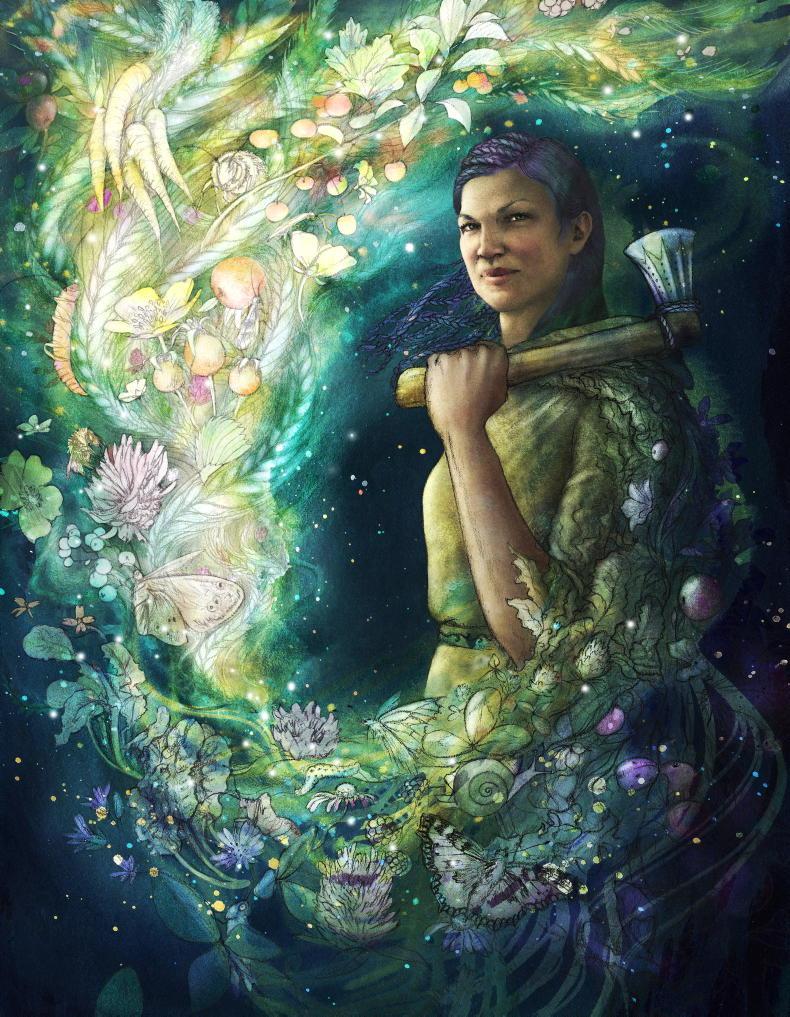

Tailtiu was the first farmer depicted in Irish mythology. \ Shona Shirley Macdonald

“She raised five children before getting her Leaving Cert and then going to college to study the classics,” explains Ellen.

“She would describe [The Táin etc] to me and tell me how these books were the equivalent of the Irish Iliad or The Odyssey, but they were so underrated in the public eye… that bothered her.”

It bothered Ellen, too, as it turned out. While working in journalism and communications after college, she started “to dig” a bit deeper into Irish mythology and uncovered the stories of Irish goddesses that had been, essentially, written out of modern re-tellings.

But why did this happen?

“A lot of our stories have been sanitised,” Ellen responds. “I do think there was this reticence to teach Irish children about ancient Gods, which is contradictory, because actually the stories were written down by Christian scribes.”

Furthermore, she adds, in the Celtic revival of the early 1900s, the likes of Finn mac Cumhaill or Cú Chulainn were chosen as “mascots for Irish nationalism”, while the female characters were cherry-picked often for qualities such as their renowned beauty or as passive love interests.

“Goddesses that embodied other qualities – be they death prophets or warriors – just weren’t seen as obviously suitable for the time,” says Ellen. “And that’s just permeated down through the years.”

Medb and menstruation

The more that she researched and read, however, the more convinced she was that she had to “bring these goddesses to light”.

“I immediately found them very relatable and I could see parallels to contemporary issues for women,” says Ellen of her idea to retell the stories for younger readers.

The goddess Bé Binn represents the importance of body confidence for Ellen Ryan. \ Shona Shirley Macdonald

Ellen drew a lot on the Táin, but also from Acallam na Senórach (Tales of the Elders of Ireland) and translations of ancient texts in the UCC CELT project. She also visited archaeological sites associated with Irish goddesseses, like Rathcroghan in Co Roscommon, which is said to have been home to Queen Medb and where Oweynagat, the Cave of the Cats, has a strong link to The Morigan.

As referenced earlier, Medb has often been depicted as “greedy”, given her relentless and bloody pursuit of the brown bull of Cooley in order to match her husband’s assets. Ellen, however, argues that there was more to this story than meets the eye.

“The Brehon Laws were active at that time and in the Brehon Laws, if a woman has equal wealth to her husband, she also has equal rights, she has autonomy and independence. So, it was far more than, ‘I need to have this bull,’” she explains.

“As a queen ruling her people, she needed to have autonomy from her husband.”

Another aspect of the story that struck a chord with Ellen is that in the original telling of the Táin Bó Cúailnge, Medb is recorded as getting her period mid-battle and tells Fergus, her army general, that she has to take care of it.

Ellen Ryan says there is more to Queen Medb's story than meets the eye. \ Shona Shirley Macdonald

“And she’s told by Fergus: ‘This is not a good time,’” continues Ellen. “And – this is in this ancient text – she tells him: ‘I don’t choose when it comes’, educating them on how periods work, this is part of her body’s natural cycle and when it comes, she defers to it, and she gave it priority in battle and that was really powerful for me.”

Indeed, Ellen felt that it was essential to include this in her book, given that her audience is mostly nine to 12-year-old girls on the cusp of puberty.

“I wanted them to associate a period with a woman, a goddess and with a woman in battle, a woman leading men; and a woman who wasn’t afraid to speak about it to men,” says Ellen.

Tailtiu and tillage

But while many people will have heard of Medb, most of the goddesses in Girls Who Slay Monsters will be new to readers. This includes Tailtiu, who was the first farmer depicted in Irish mythology and was said to have created the field system. Indeed, The Tailteann Games (like an ancient Irish Olympics) were named in her honour.

In her story, Tailtiu leaves her homeland of Spain to come to Ireland to teach the tribes how to till the land and grow crops, and thus avoid struggle, starvation and warfare.

To Ellen, this goddess represents the importance of farming and food production in bringing peace and harmony to society.

Author Ellen Ryan, pictured at the An Post Irish Book Awards. \ Ger Holland

“They [the tribes] were able to reap the crops at certain seasons, share the food and live in a way that they didn’t have to fight anymore. So farming made their society work, it made their society sustainable and I thought that was so beautiful; that farming could unify people,” says Ellen.

“She was a hero. She gave them civilisation, she gave them unity and peace in showing them how to farm and I think that’s so incredible.”

Bé Binn and body confidence

Another goddess who Ellen believes has as much relevance today as in ancient times – and the one she most personally connects with – is Bé Binn.

A giant and a fashionista who is brimming with confidence at the beginning of the story, Bé Binn starts to doubt herself after being bullied about her appearance. But when she realises her own worth again, she is able to harness her powers and stand up for herself.

“It’s a great coming-of-age story, because she has to find that confidence in herself again, she has to believe in herself without validation,” says Ellen.

“And it’s just such an important thing that everyone – boys as well – everyone has to do at times in their life. We have to dig deep and find our own self-worth without it being handed to us by others, because otherwise we become so reliant on other people’s approval and obviously that is so relevant to today’s culture with social media as well.”

Bríg and reinvention

Given the upcoming bank holiday weekend in honour of St Brigid, Ellen also shares the story of the goddess, Bríg, along with some details that might surprise readers.

“Bríg was a goddess of invention; she not only created the whistle, but she created the ancient healing art form of keening, which comes from caoineadh, which is crying,” says Ellen, explaining that according to mythology, Bríg initiated this ancient lament for the dead after her son was killed in battle.

Though Ellen argues that not only should Bríg be seen as a goddess of invention, but also reinvention: the original multitasker, if you will.

“She’s a really contemporary goddess in that way,” she says. “She had children, but she also went to battle. She was constantly inventing and being of use to her people and was obviously so revered that she was brought into the new religion.”

Human and flawed

It is important to Ellen, however, that not all of the goddesses were always “good” in the traditional fairy tale sense, and that they have been presented as complex characters.

“They’re goddesses, but they’re very flawed,” she says, “and ironically, they’re very human.”

As part of the promotion of the book, Ellen has been giving talks at schools nationwide. She is also currently working on a sequel, which this time will look at some of male mythological characters who go against the grain.

But ultimately, she believes that the stories of the goddesses are for all of us mere mortals.

“It’s not just about female empowerment,” she concludes. “It’s about empowerment for all of us.”

Girls Who Slay Monsters by Ellen Ryan and illustrated by Shona Shirley Macdonald is published by HarperCollins Ireland, RRP €23.

Read more

Memoir series: what’s your story?

'I was so lucky to survive... I just knew I had to write this book.'

As a child, Ellen Ryan could never “really relate” to the female characters in Irish myths and legends.

Or rather, how they had been re-written.

“Niamh was this temptress who lured Oisín away and that didn’t serve him. Medb was a greedy, cow-snatching villain. Gráinne… she’s just a damsel in distress,” she despairs.

But as the author of Girls Who Slay Monsters: Daring Tales of Ireland’s Forgotten Goddesses” which was recently named Children’s Book of the Year at the An Post Book Awards- Ellen is hoping to change the well-trodden narrative; and empower young readers in the process.

While familiar with traditional tales of Tír na nÓg or The Salmon of Knowledge from school, Ellen explains that it was her grandmother, Carmel Wood, who first introduced her to ancient texts like the Táin. This inspired her in more ways than one.

Tailtiu was the first farmer depicted in Irish mythology. \ Shona Shirley Macdonald

“She raised five children before getting her Leaving Cert and then going to college to study the classics,” explains Ellen.

“She would describe [The Táin etc] to me and tell me how these books were the equivalent of the Irish Iliad or The Odyssey, but they were so underrated in the public eye… that bothered her.”

It bothered Ellen, too, as it turned out. While working in journalism and communications after college, she started “to dig” a bit deeper into Irish mythology and uncovered the stories of Irish goddesses that had been, essentially, written out of modern re-tellings.

But why did this happen?

“A lot of our stories have been sanitised,” Ellen responds. “I do think there was this reticence to teach Irish children about ancient Gods, which is contradictory, because actually the stories were written down by Christian scribes.”

Furthermore, she adds, in the Celtic revival of the early 1900s, the likes of Finn mac Cumhaill or Cú Chulainn were chosen as “mascots for Irish nationalism”, while the female characters were cherry-picked often for qualities such as their renowned beauty or as passive love interests.

“Goddesses that embodied other qualities – be they death prophets or warriors – just weren’t seen as obviously suitable for the time,” says Ellen. “And that’s just permeated down through the years.”

Medb and menstruation

The more that she researched and read, however, the more convinced she was that she had to “bring these goddesses to light”.

“I immediately found them very relatable and I could see parallels to contemporary issues for women,” says Ellen of her idea to retell the stories for younger readers.

The goddess Bé Binn represents the importance of body confidence for Ellen Ryan. \ Shona Shirley Macdonald

Ellen drew a lot on the Táin, but also from Acallam na Senórach (Tales of the Elders of Ireland) and translations of ancient texts in the UCC CELT project. She also visited archaeological sites associated with Irish goddesseses, like Rathcroghan in Co Roscommon, which is said to have been home to Queen Medb and where Oweynagat, the Cave of the Cats, has a strong link to The Morigan.

As referenced earlier, Medb has often been depicted as “greedy”, given her relentless and bloody pursuit of the brown bull of Cooley in order to match her husband’s assets. Ellen, however, argues that there was more to this story than meets the eye.

“The Brehon Laws were active at that time and in the Brehon Laws, if a woman has equal wealth to her husband, she also has equal rights, she has autonomy and independence. So, it was far more than, ‘I need to have this bull,’” she explains.

“As a queen ruling her people, she needed to have autonomy from her husband.”

Another aspect of the story that struck a chord with Ellen is that in the original telling of the Táin Bó Cúailnge, Medb is recorded as getting her period mid-battle and tells Fergus, her army general, that she has to take care of it.

Ellen Ryan says there is more to Queen Medb's story than meets the eye. \ Shona Shirley Macdonald

“And she’s told by Fergus: ‘This is not a good time,’” continues Ellen. “And – this is in this ancient text – she tells him: ‘I don’t choose when it comes’, educating them on how periods work, this is part of her body’s natural cycle and when it comes, she defers to it, and she gave it priority in battle and that was really powerful for me.”

Indeed, Ellen felt that it was essential to include this in her book, given that her audience is mostly nine to 12-year-old girls on the cusp of puberty.

“I wanted them to associate a period with a woman, a goddess and with a woman in battle, a woman leading men; and a woman who wasn’t afraid to speak about it to men,” says Ellen.

Tailtiu and tillage

But while many people will have heard of Medb, most of the goddesses in Girls Who Slay Monsters will be new to readers. This includes Tailtiu, who was the first farmer depicted in Irish mythology and was said to have created the field system. Indeed, The Tailteann Games (like an ancient Irish Olympics) were named in her honour.

In her story, Tailtiu leaves her homeland of Spain to come to Ireland to teach the tribes how to till the land and grow crops, and thus avoid struggle, starvation and warfare.

To Ellen, this goddess represents the importance of farming and food production in bringing peace and harmony to society.

Author Ellen Ryan, pictured at the An Post Irish Book Awards. \ Ger Holland

“They [the tribes] were able to reap the crops at certain seasons, share the food and live in a way that they didn’t have to fight anymore. So farming made their society work, it made their society sustainable and I thought that was so beautiful; that farming could unify people,” says Ellen.

“She was a hero. She gave them civilisation, she gave them unity and peace in showing them how to farm and I think that’s so incredible.”

Bé Binn and body confidence

Another goddess who Ellen believes has as much relevance today as in ancient times – and the one she most personally connects with – is Bé Binn.

A giant and a fashionista who is brimming with confidence at the beginning of the story, Bé Binn starts to doubt herself after being bullied about her appearance. But when she realises her own worth again, she is able to harness her powers and stand up for herself.

“It’s a great coming-of-age story, because she has to find that confidence in herself again, she has to believe in herself without validation,” says Ellen.

“And it’s just such an important thing that everyone – boys as well – everyone has to do at times in their life. We have to dig deep and find our own self-worth without it being handed to us by others, because otherwise we become so reliant on other people’s approval and obviously that is so relevant to today’s culture with social media as well.”

Bríg and reinvention

Given the upcoming bank holiday weekend in honour of St Brigid, Ellen also shares the story of the goddess, Bríg, along with some details that might surprise readers.

“Bríg was a goddess of invention; she not only created the whistle, but she created the ancient healing art form of keening, which comes from caoineadh, which is crying,” says Ellen, explaining that according to mythology, Bríg initiated this ancient lament for the dead after her son was killed in battle.

Though Ellen argues that not only should Bríg be seen as a goddess of invention, but also reinvention: the original multitasker, if you will.

“She’s a really contemporary goddess in that way,” she says. “She had children, but she also went to battle. She was constantly inventing and being of use to her people and was obviously so revered that she was brought into the new religion.”

Human and flawed

It is important to Ellen, however, that not all of the goddesses were always “good” in the traditional fairy tale sense, and that they have been presented as complex characters.

“They’re goddesses, but they’re very flawed,” she says, “and ironically, they’re very human.”

As part of the promotion of the book, Ellen has been giving talks at schools nationwide. She is also currently working on a sequel, which this time will look at some of male mythological characters who go against the grain.

But ultimately, she believes that the stories of the goddesses are for all of us mere mortals.

“It’s not just about female empowerment,” she concludes. “It’s about empowerment for all of us.”

Girls Who Slay Monsters by Ellen Ryan and illustrated by Shona Shirley Macdonald is published by HarperCollins Ireland, RRP €23.

Read more

Memoir series: what’s your story?

'I was so lucky to survive... I just knew I had to write this book.'

SHARING OPTIONS