Recent analysis presented at last week’s Teagasc Let’s Talk Sheep webinar showed the huge effect that liver fluke infection is having on the sector, with costs estimated at €1.2m/annum.

Dr Orla Keane, researcher in the Teagasc Animal and Bioscience Department, said these losses cumulate from several areas.

These include reduced performance and loss of body condition, lower litter size, a wider lambing spread, poor thrive and food conversion efficiency in lambs, a loss in the value of livers to the processing sector and higher mortality.

Orla outlined that the risk of liver fluke varies from year-to-year and is also farm-specific. The threat is generally greatest in damp, poorly drained conditions and where weather provides the ideal environment for the liver fluke parasite to complete its life cycle.

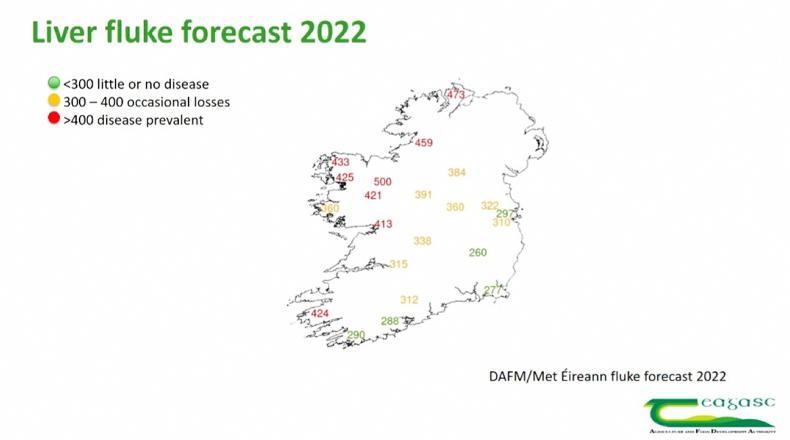

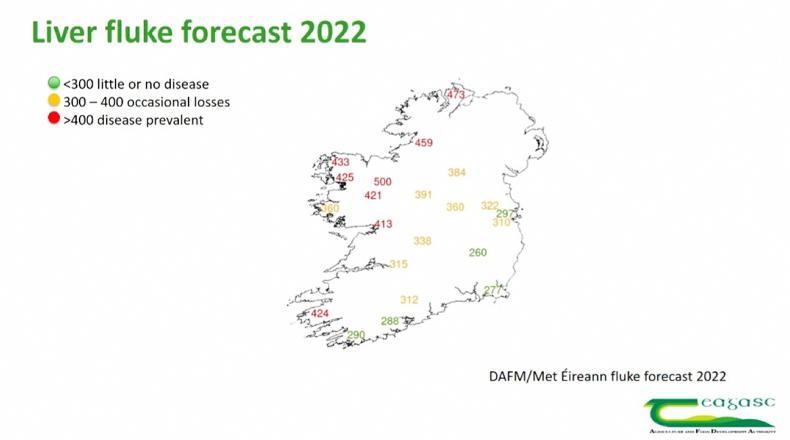

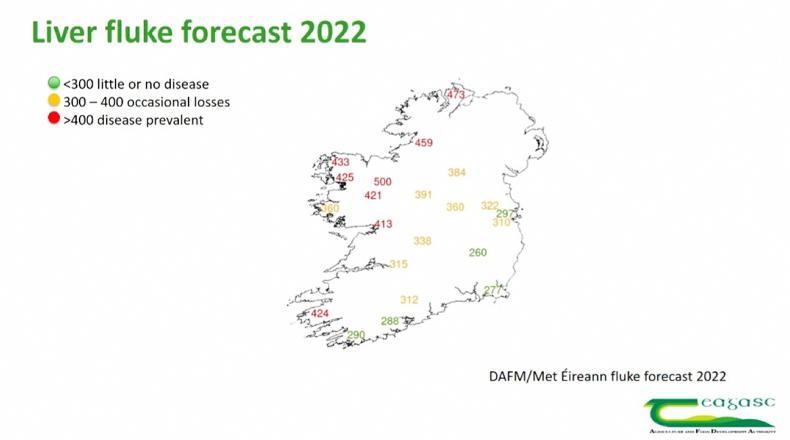

The Department of Agriculture’s liver fluke forecast was highlighted as a useful tool in determining the threat. This year’s forecast has predicted a high risk of losses due to liver fluke in the northwest, with a high risk right along the western coast.

Diagnostic tools

In addition to the liver fluke forecast, Orla outlined a number of important diagnostic tools which farmers should make use of.

The farm history is the first port of call as previous experience will shed light on the grazing areas of the farm posing the greatest risk.

Post-mortem examination of livers will give an immediate indication on the health of livers and presence of active liver fluke.

On a similar level, any sudden deaths should be investigated.

There are three tests that can also play a role. Faecal egg counts (FECs) can be useful to identify if liver fluke parasites are present. There are limitations, however, with FECs in that they work by identifying liver fluke eggs.

It takes 10 to 12 weeks for the liver fluke parasite to reach adult or mature stage and prior to this huge damage could be done to the liver depending on the level of infection. Therefore, FECs are seen as part of an overall control programme to identify fluke at certain times of the year and to check that active ingredients are effective.

Figure 1: The liver fluke forecast shows the highest risk of infection in the northwest and other parts of the western coast.

A coproantigen test is another laboratory method that can be used to identify the presence of fluke at an earlier stage but the test is not readily used. Serum antibody tests are blood tests that are used by the Department of Agriculture as part of their screening process. These tests will also identify the stage of fluke quite early, but a limitation is that they will be influenced by historic disease for three to four weeks after fluke have been killed and therefore cannot distinguish between active or historic disease.

Control programme

Orla advised that a fluke control programme should take into account risk factors across the year and not just at the high-risk periods.

A spring treatment will prevent snails becoming infected while the main focus in summer months is on reducing the snail population, of which weather has the greatest effect.

In autumn, the aim is to prevent animals from grazing high-risk areas to avoid acute liver fluke, while also preventing immature migration and development. The focus in winter is treatment of high-risk animals, killing adult and immature fluke stages and preventing liver fluke damage and ill-thrift due to chronic infection.

Treatment

The most important factor when treating sheep is that you select an active ingredient that kills the target stage of the liver fluke parasite and that practices such as dosing to the correct weight and ensuring the correct volume is administered (calibration of the dosing gun) are followed.

Table 1 outlines the active ingredients available and the optimum timing for their use. Orla cautioned farmers to be careful when using closantel and rafoxanide products as these are very closely related and switching between using these ingredients is not the same as using different active ingredients to slow down the rate at which resistance develops.

The threat of liver fluke is high this season in the northwest.Farmers should avail of all information available in determining the need to treat animals. FECs can play a role in a fluke control programme but beware of their limitations.Select the appropriate active ingredient for the time of year and target stage of the liver fluke parasite. There was keen interest on the evening and some of the main questions and answers are summarised below

Would the recent heavy frost reduce the risk of liver fluke infestations by killing off larvae on pasture?

The liver fluke parasites are pretty resilient and can withstand extremes in weather. I wouldn’t be confident the frost [we experienced recently] would kill them off.

Have you seen much rumen fluke this year?

We have seen it mainly in the northwest. The regional veterinary lab in Sligo has recorded some cases but it is important to remember that problems are often farm-specific and there needs to be a demonstrated need to treat animals.

Are we in trouble the fact that Trodax is no longer available?

It leaves us with fewer options which is not good in terms of guarding against resistance. Moves are afoot to bring in other nitroxynil-based products to Ireland.

Where can liver fluke samples be sent to carry out a faecal egg count to determine the need to dose?

The Department of Agriculture website lists laboratories which are approved for testing for the presence of liver fluke eggs.

Are there any updates on the development of a liver fluke vaccine?

We are actively working on a vaccine with collaborators in Galway. There is no licensed vaccine on the market but work is continuing to develop such a vaccine.

Do fluke infections build up over time?

The liver fluke parasite can live a long time in animals so, over time, there can be a buildup of infection. When the level of infection reaches a certain threshold, it will start to become obvious and this is the case with chronic fluke, in particular, with characteristic signs such as sheep losing body condition, displaying signs of anaemia and the typical ‘bottle jaw’ symptom.

Is it safe to use liver fluke products in late pregnancy?

As with all veterinary medicines it is important to consult product guidelines. We generally tend to avoid dosing heavily pregnant ewes in the final four weeks pre-lambing as the aim is to keep handling to a minimum and target any treatments before this window.

Is it a good idea to treat individual animals displaying signs of liver fluke similar to the practice of not treating healthy sheep for worms?

With liver fluke, it is probably better to carry out treatment on a flock or batch level. This way you can be sure that you are targeting any underlying issues as sheep do not develop a natural immunity and in a group, if some are affected, it is likely that the group will be. You will also reduce the level of larvae being shed on to pasture too.

Recent analysis presented at last week’s Teagasc Let’s Talk Sheep webinar showed the huge effect that liver fluke infection is having on the sector, with costs estimated at €1.2m/annum.

Dr Orla Keane, researcher in the Teagasc Animal and Bioscience Department, said these losses cumulate from several areas.

These include reduced performance and loss of body condition, lower litter size, a wider lambing spread, poor thrive and food conversion efficiency in lambs, a loss in the value of livers to the processing sector and higher mortality.

Orla outlined that the risk of liver fluke varies from year-to-year and is also farm-specific. The threat is generally greatest in damp, poorly drained conditions and where weather provides the ideal environment for the liver fluke parasite to complete its life cycle.

The Department of Agriculture’s liver fluke forecast was highlighted as a useful tool in determining the threat. This year’s forecast has predicted a high risk of losses due to liver fluke in the northwest, with a high risk right along the western coast.

Diagnostic tools

In addition to the liver fluke forecast, Orla outlined a number of important diagnostic tools which farmers should make use of.

The farm history is the first port of call as previous experience will shed light on the grazing areas of the farm posing the greatest risk.

Post-mortem examination of livers will give an immediate indication on the health of livers and presence of active liver fluke.

On a similar level, any sudden deaths should be investigated.

There are three tests that can also play a role. Faecal egg counts (FECs) can be useful to identify if liver fluke parasites are present. There are limitations, however, with FECs in that they work by identifying liver fluke eggs.

It takes 10 to 12 weeks for the liver fluke parasite to reach adult or mature stage and prior to this huge damage could be done to the liver depending on the level of infection. Therefore, FECs are seen as part of an overall control programme to identify fluke at certain times of the year and to check that active ingredients are effective.

Figure 1: The liver fluke forecast shows the highest risk of infection in the northwest and other parts of the western coast.

A coproantigen test is another laboratory method that can be used to identify the presence of fluke at an earlier stage but the test is not readily used. Serum antibody tests are blood tests that are used by the Department of Agriculture as part of their screening process. These tests will also identify the stage of fluke quite early, but a limitation is that they will be influenced by historic disease for three to four weeks after fluke have been killed and therefore cannot distinguish between active or historic disease.

Control programme

Orla advised that a fluke control programme should take into account risk factors across the year and not just at the high-risk periods.

A spring treatment will prevent snails becoming infected while the main focus in summer months is on reducing the snail population, of which weather has the greatest effect.

In autumn, the aim is to prevent animals from grazing high-risk areas to avoid acute liver fluke, while also preventing immature migration and development. The focus in winter is treatment of high-risk animals, killing adult and immature fluke stages and preventing liver fluke damage and ill-thrift due to chronic infection.

Treatment

The most important factor when treating sheep is that you select an active ingredient that kills the target stage of the liver fluke parasite and that practices such as dosing to the correct weight and ensuring the correct volume is administered (calibration of the dosing gun) are followed.

Table 1 outlines the active ingredients available and the optimum timing for their use. Orla cautioned farmers to be careful when using closantel and rafoxanide products as these are very closely related and switching between using these ingredients is not the same as using different active ingredients to slow down the rate at which resistance develops.

The threat of liver fluke is high this season in the northwest.Farmers should avail of all information available in determining the need to treat animals. FECs can play a role in a fluke control programme but beware of their limitations.Select the appropriate active ingredient for the time of year and target stage of the liver fluke parasite. There was keen interest on the evening and some of the main questions and answers are summarised below

Would the recent heavy frost reduce the risk of liver fluke infestations by killing off larvae on pasture?

The liver fluke parasites are pretty resilient and can withstand extremes in weather. I wouldn’t be confident the frost [we experienced recently] would kill them off.

Have you seen much rumen fluke this year?

We have seen it mainly in the northwest. The regional veterinary lab in Sligo has recorded some cases but it is important to remember that problems are often farm-specific and there needs to be a demonstrated need to treat animals.

Are we in trouble the fact that Trodax is no longer available?

It leaves us with fewer options which is not good in terms of guarding against resistance. Moves are afoot to bring in other nitroxynil-based products to Ireland.

Where can liver fluke samples be sent to carry out a faecal egg count to determine the need to dose?

The Department of Agriculture website lists laboratories which are approved for testing for the presence of liver fluke eggs.

Are there any updates on the development of a liver fluke vaccine?

We are actively working on a vaccine with collaborators in Galway. There is no licensed vaccine on the market but work is continuing to develop such a vaccine.

Do fluke infections build up over time?

The liver fluke parasite can live a long time in animals so, over time, there can be a buildup of infection. When the level of infection reaches a certain threshold, it will start to become obvious and this is the case with chronic fluke, in particular, with characteristic signs such as sheep losing body condition, displaying signs of anaemia and the typical ‘bottle jaw’ symptom.

Is it safe to use liver fluke products in late pregnancy?

As with all veterinary medicines it is important to consult product guidelines. We generally tend to avoid dosing heavily pregnant ewes in the final four weeks pre-lambing as the aim is to keep handling to a minimum and target any treatments before this window.

Is it a good idea to treat individual animals displaying signs of liver fluke similar to the practice of not treating healthy sheep for worms?

With liver fluke, it is probably better to carry out treatment on a flock or batch level. This way you can be sure that you are targeting any underlying issues as sheep do not develop a natural immunity and in a group, if some are affected, it is likely that the group will be. You will also reduce the level of larvae being shed on to pasture too.

SHARING OPTIONS