Pierre Henri Hamon runs the largest contracting business in France. Only 36 years of age, he took over the business from his family just nine years ago, but has grown it sixfold in almost as many years. Based in Brittany in western France, he runs 65 tractors, 30 combines and 12 foragers and caters for over 1,000 farmer clients.

Background

While studying agricultural science in college, Pierre spent his summers working abroad. These experiences included a season working with contractors in England, a summer learning about the sugar cane industry in Brazil and a season in Sweden learning about the biomass industry. He later spent time in Germany learning about precision farming, which morphed its way into a full-time role with John Deere as dealer support for precision farming equipment.

“I spent five years with John Deere, saw a lot and learnt a lot. There was a great opportunity for progression but I’d reached the point where I wanted to return home and farm. In 2013, at the age of 27, I returned home full-time. Two weeks later a farmer called and offered me an opportunity to buy 50ha of land and rent a further 50ha. I took him up on the opportunity. It cost in the region of €4,000-5,000/ha and I still farm this land today. This provided me with a good start.

Hamon runs 110 self-propelled machines and around 200 trailed implements.

“My grandfather and father were agricultural contractors and farmers. My grandfather started contracting in 1947 while farming 5ha of land. By 1978 the contracting business had expanded to eight combines with 10-15 staff. At the same time CUMA (group machine ownership) was becoming very popular and left contractors struggling to find work.

He decided get out of contracting and focus on farming at which point he had 70ha of land and kept 70 cows. “Nine years later in 1987 my father decided to re-enter contracting, having discovered the renewed demand among local farmers given the increase in farm sizes.

Pierre Henri Hamon.

“When I returned home to the business, we had 12 tractors, six combines and three foragers. I worked as an employee for two years to make sure it really was something I wanted to do, and so it was. But, in order for there to be a future I felt I needed to take it to the next level.”

Growing the business

In 2015, Pierre bought out another contractor. The owner, who was 52, had enough of the business and wanted to retire. This was the start of the expansion. In 2017, 2018, 2020 and 2021 Pierre bought four more contracting businesses. He explained that he didn’t necessarily go looking to buy out these businesses, but that the opportunities arose for him.

Hamon runs six McHale Fusion balers and loves them.

“Each business was unique. I estimate that client retention from taking over another contractor was around 50-70%. I often see those customers who left return after two or three years. One thing I don’t do is get new customers based on price. Because these type of clients will leave you again for the next cheapest contractor.

“With the takeover of the other businesses, it became large enough to put management staff in place. We now are working out of six depots with a manager in each who essentially runs that smaller business.

“It's hard to quantify how much work we do each year. I estimate we are doing some jobs on 42,000ha".

“I have two staff who oversee three depots each. They are heavily involved in planning and logistics. They gather data and push data and technology on to farmers such as yield mapping and NIR systems.

“We have weather stations scattered all over the areas we work in. Weather data and rainfall are checked every morning before staff head off in the tractors, so we know we won’t be stopped up. We work in a 100km radius from our main yard and travel around 30km from each site for work, but sometimes we often go further. Annual rainfall within this radius can vary from 700mm to 1,100mm.

Customers

“We have 1,000 farmer customers on the books. Around 80% of our turnover is through 20% of our customers. The average customer farm size is 150ha but we have customers with holdings ranging from 1ha right up to 1,500ha, so we deal with all. The average field size we work is less than 3ha. Some 98-99% of our customers never change contractor – there is a great loyalty with most customers. Our average customer would cut 50ha of maize annually. The average farm in this region is around 150ha.

“It’s hard to quantify how much work we do each year. I estimate we are doing some jobs on 42,000ha. We combine around 10,000ha, plant and harvest 5,000ha of maize, spread 3,000ha of fertiliser and make 45,000 bales. I’m not sure how much grass we harvest as the foragers and the wagons are charged out on an hourly basis.

Staff

“We employ 61 full-time staff all of whom are French. This includes six office staff, six managers, two in planning and logistics and two mechanics, and 45 drivers. I also employ 10 part-time drivers. The majority of staff have been with me for years. I’d guess that over half the team have been with the business for over 10 years. I try to pay my staff well to keep them, I’d like to think I’m the best-paying contractor in the region.

“All staff are paid on an hourly basis. We use time sheets where everyone clocks in and clocks out. We will be moving to an app system shortly though.”

Machinery

Historically, the family has always operated John Deere tractors, but Fendt has made inroads in recent years. Pierre’s first experience with Fendt was through a contracting business he purchased. At the moment there are 110 self-propelled machines and around 200 trailed implements. In terms of tractors, there are 45 John Deeres and 20 Fendts. These range from 120hp up to 500hp including Fendt’s flagship 1050 Vario.

“We employ 61 full time staff.This includes six office staff, six managers, two in planning and logistics and two mechanics, and 45 drivers".

“Last year, we bought 14 new tractors, – 10 John Deeres and four Fendts. We try to keep the same drivers on the same tractor, but this isn’t always possible.

“We run all John Deere foragers, but I’m open to changing brands. I quite like the Krone. If I do change, I will probably buy four or five of that particular It’s important for me to have a stock of spare parts on the shelf. So, the more similarity in machines, the better. At the moment the fleet comprises eight 8000 series, one 9900i and three older 7000 series machines that are used for grass silage and as backup machines.”

In addition, the fleet is made up of 30 combines, six McHale Fusion balers, two self-propelled sprayers, one self-propelled beet harvester, 12 slurry tankers, 15 muck spreaders, 15 mowers (five butterflies, 10 trailed), 15 drills and three forage wagons.

Hamon estimates that he has €200,000 to €300,000 worth of parts in stock at any one time, and uses €1.5 million worth of parts annually.

“As the business has expanded so much each year, we don’t have a set policy of changing machines. We’ve had to keep most machines and just buy more. In the near future, I would like to see it getting to a stage where we change the tractors after five to seven years, and keep machines within warranty. Typically, our tractors would be doing 1,500 hours/year. This year we will replace a minimum number of machines due to rising costs and instead wait and see what happens next year.

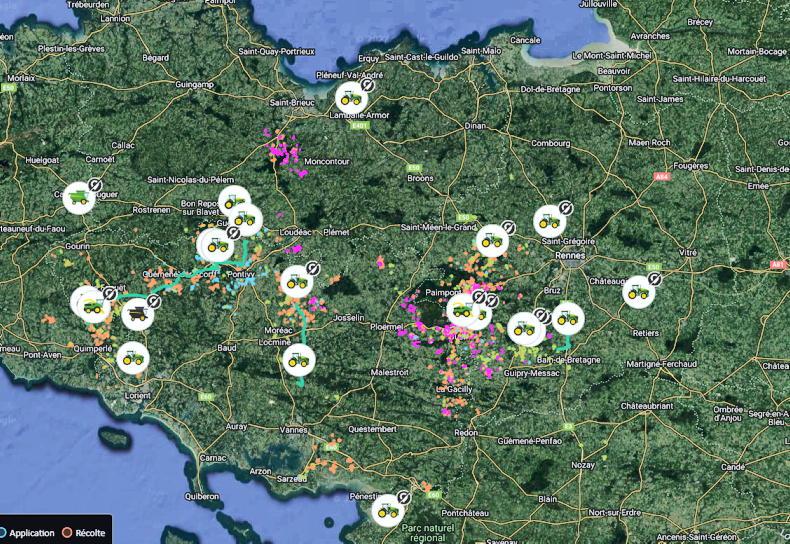

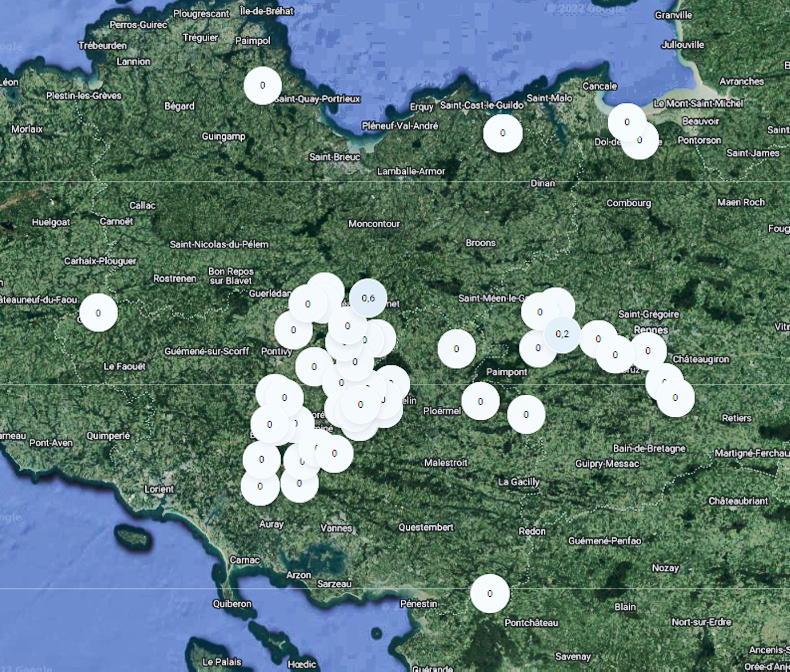

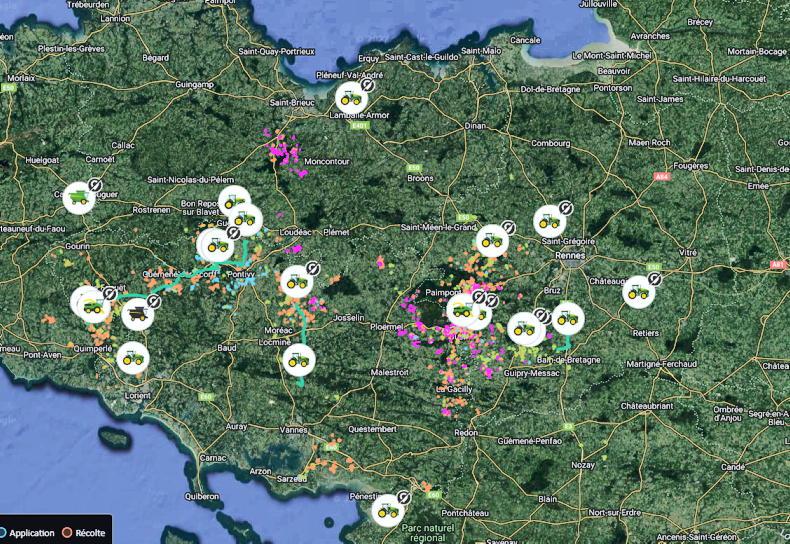

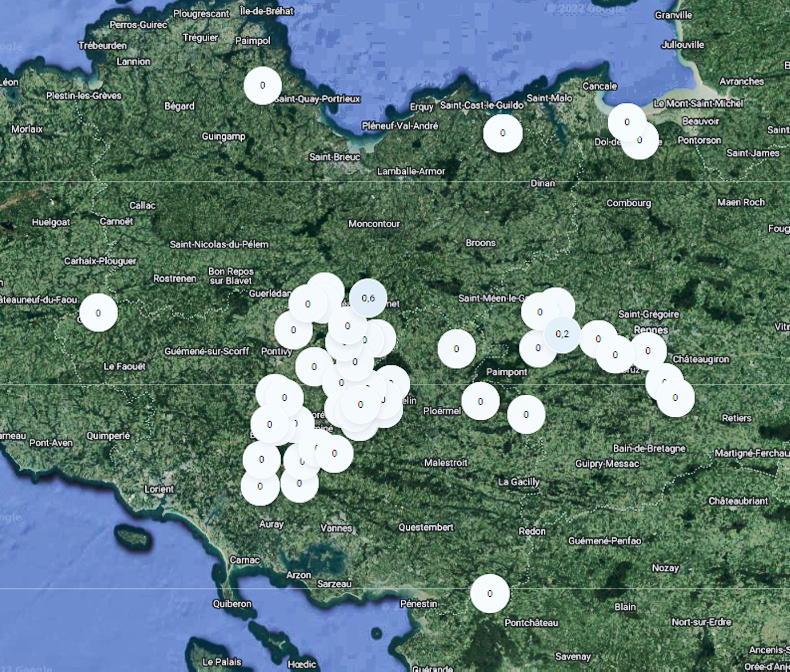

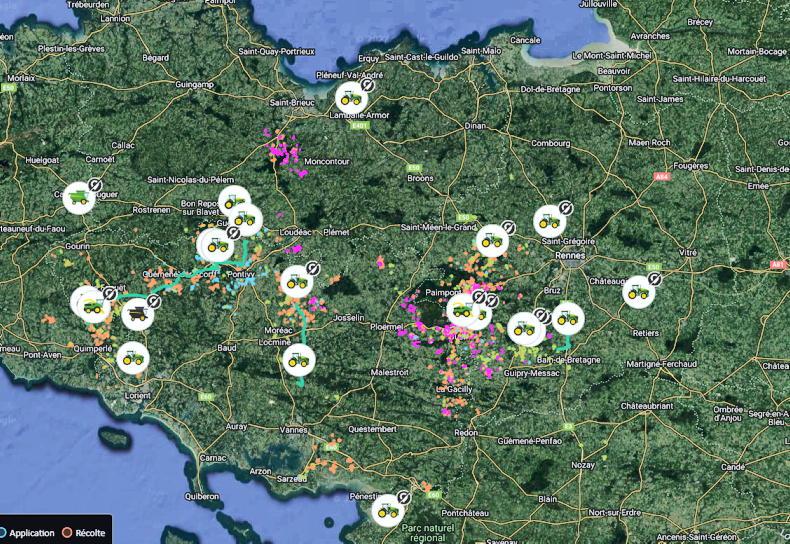

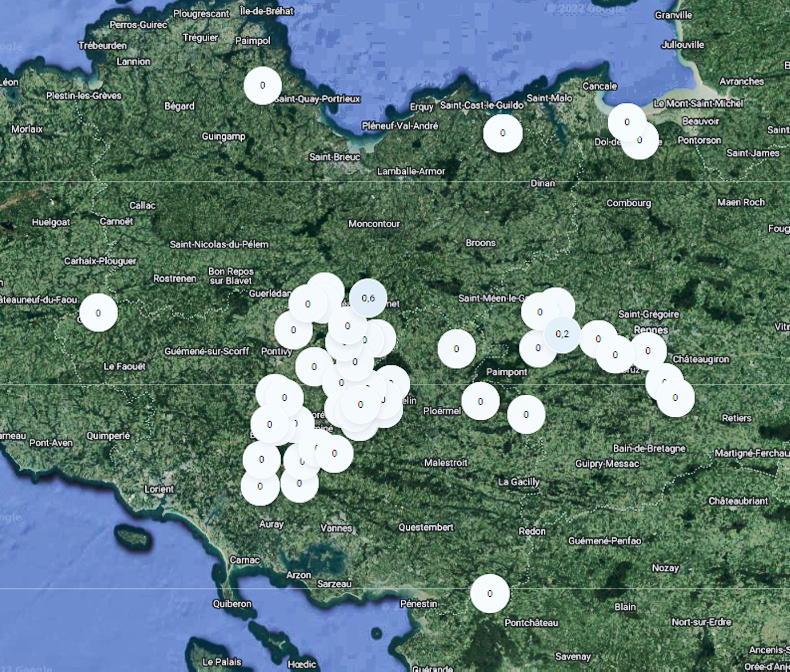

Pierre uses the 'My John Deere' app - the picture shows where his JD machines were working at the time of our visit.

“When it comes to buying and upgrading machinery, it involves a conversation with the managers on what they need and what they want. We then negotiate the price with the dealer and go from there.”

Parts

Pierre has a very impressive stock of parts at his home base, and carries some stock of parts at his other depots. He estimates that he has €200,000 to €300,000 worth of parts in stock at any one time, and uses €1.5m worth of parts annually.

He tries to carry all major wearing parts in stock, along with having his own mechanics.

When it comes to repairs, he said a mechanic would typically cost €100 for a callout fee, and €80/hour thereafter, rising to €100/hour at the weekend. “We carry out 80% of the mechanical work ourselves, while diagnostic work is done by the dealers. In general, for buying parts, we work through a national buying group of contractors.”

Rates and invoicing

Like in New Zealand, mowers, rakes, wagons and foragers are all charged out on an hourly basis. Mowing with butterflies would cost you €220/hour, while a tri-axle wagon would cost €90/hour and then €104/load thereafter.

The roof of his most recently built machinery storage shed was fitted with solar panels.

Pushing up silage is all carried out with tractors, and not wheel loaders like is commonplace in Ireland. A tractor on the pit would cost up to €100/hour, depending on its size. Meanwhile, baling and wrapping with a fusion would cost you €16/bale. Slurry application through a Vervaet self-propelled tanker with a disc injector is priced at €210/hour.

Hamon has two full-time mechanics and carries out 80% of the mechanical work in-house.

“Invoices are sent out to customers at the end of every month. Some farmers will pay monthly but more will pay once a year. I honestly feel that my business is less profitable than a typical smaller contracting business. But I am looking to the future.”

Contracting in France

In France, the term agricultural contractor is pretty much unrecognised. It is instead given the name entrepreneur travel agriculture (ETA).

Hamon has weather stations scattered all over the areas he works.

“Through my previous role with John Deere I’ve visited many contractors all over Europe. No matter where you go, contracting is the same all over the world. Farmers want to know you; they want to have your mobile number and they want the best service possible at the lowest price. The average contractor in France would employ two to three drivers – in this area they are a little larger – they might employ 10 staff. In my area, you would have a CUMA group and two contractors typically within a 5km radius.

Staff training.

“The big downfall I see with contracting is that it’s a race to the bottom – who will be the last to die kind of a thing. When I decided to come home and take over the business, I wanted to set a new strategy, take a new approach.

“I set out a meeting with other large contractors in the region who I knew I could work with. I proposed that we change how we do business, we hire agronomists, we push precision agriculture and soil health.

The fleet includes 12 large slurry tankers and 15 muck spreaders.

“We wanted to be a step above the rest, and offer more to the farmers. So, we came together and set up a company.

“This has proved very successful. Our company is made up of 16/17 very good contractors, and between us we employ 450 drivers. We all continue to run our own businesses separately, but the company employs two full-time agronomists who offer advice to our farmers. The company also acts as a buyer group for parts and plastic, and has started carrying out tests for chemical company Bayer.

“CUMA, rather than another contractor, is my biggest competition, but I feel it's becoming less and less popular in this area".

“All of the contractors work in defined areas, which means we work hand in hand and help each other out when we are stuck.”

CUMA

Just down the road from Pierre’s yard is a large CUMA group. This particular CUMA group has its own workshop, several large machinery storage sheds and a serious fleet of kit – probably as much kit as you would spot in any Irish contractor’s yard.

"Our average customer would cut 50ha of maize annually. The average farm in this region is around 150ha”.

“CUMA, rather than another contractor, is my biggest competition, but I feel it’s becoming less and less popular in this area. The bigger farmers want a good professional service.

“I’ve found that some of the farmers who are involved in CUMA, generally don’t want to use a contractor anyway – there’s a lot of politics in it.”

GPS theft

Machinery theft is a problem everywhere, especially when it comes to GPS Pierre has endured a very difficult time with thieves stopping in on several occasions to steal John Deere GPS guidance systems, including both screens and receivers.

“We have 1,000 farmer customers on the books. Around 80% of our turnover is through 20% of our customers. The average customer farm size is 30ha-40ha".

“On the first occasion, thieves came into my yard at night and stole 15 John Deere guidance systems. They came a second time and stole eight more. In total this has cost me €100,000.

“The only way we can keep the systems safe is by taking them off every tractor every night, there’s no other solution at the moment.”

Brittany region

Brittany is region in the west of France. Pierre described it as having a Celtic culture.

France is eight times the size of Ireland, but to put it into perspective, Brittany is almost the size of Connacht and Leinster combined.

Brittany has a high concentration of livestock farming. For example, 55% of France’s cows and 60% of France’s pig farmers are in the Brittany region.

"We work in a 100km radius from our main yard and travel around 30km from each site for work, but sometimes we often go further"

The knock-on effect of this is that 72% of French contractors are also situated in the region, roughly totalling 1,500 contractors. The average price of land in the Brittany region is €15,000/ha.

The professionalism of the contracting business was really interesting. It was operated as a proper business. The way contracting businesses are bought and sold, with echoes of what we’ve previously reported from New Zealand, was also interesting.

The roof of Pierre’s most recently built machinery storage shed was fitted from top to bottom with solar panels. The power being generated is being sold back to the grid at 9.5c/unit, and is locked into a 20-year agreement.

While travelling through France, Peter Thomas Keaveney and Gary Abbott visited Hamon et Fils, Frances largest contractor who operates 65 tractors across six depots.

One thing that caught our attention when we visited was how some farmers approach the contractor. For example, Pierre was approached from a large farmer through LinkedIn while we were chatting to him – not something you’d see in Ireland. He didn’t blink as eyelid, and fully expected to be working for him next year following the approach.

Slurry application through a Vervaet self-propelled tanker with a disc injector in the region is priced at €210/hour.

Pierre Henri Hamon runs the largest contracting business in France. Only 36 years of age, he took over the business from his family just nine years ago, but has grown it sixfold in almost as many years. Based in Brittany in western France, he runs 65 tractors, 30 combines and 12 foragers and caters for over 1,000 farmer clients.

Background

While studying agricultural science in college, Pierre spent his summers working abroad. These experiences included a season working with contractors in England, a summer learning about the sugar cane industry in Brazil and a season in Sweden learning about the biomass industry. He later spent time in Germany learning about precision farming, which morphed its way into a full-time role with John Deere as dealer support for precision farming equipment.

“I spent five years with John Deere, saw a lot and learnt a lot. There was a great opportunity for progression but I’d reached the point where I wanted to return home and farm. In 2013, at the age of 27, I returned home full-time. Two weeks later a farmer called and offered me an opportunity to buy 50ha of land and rent a further 50ha. I took him up on the opportunity. It cost in the region of €4,000-5,000/ha and I still farm this land today. This provided me with a good start.

Hamon runs 110 self-propelled machines and around 200 trailed implements.

“My grandfather and father were agricultural contractors and farmers. My grandfather started contracting in 1947 while farming 5ha of land. By 1978 the contracting business had expanded to eight combines with 10-15 staff. At the same time CUMA (group machine ownership) was becoming very popular and left contractors struggling to find work.

He decided get out of contracting and focus on farming at which point he had 70ha of land and kept 70 cows. “Nine years later in 1987 my father decided to re-enter contracting, having discovered the renewed demand among local farmers given the increase in farm sizes.

Pierre Henri Hamon.

“When I returned home to the business, we had 12 tractors, six combines and three foragers. I worked as an employee for two years to make sure it really was something I wanted to do, and so it was. But, in order for there to be a future I felt I needed to take it to the next level.”

Growing the business

In 2015, Pierre bought out another contractor. The owner, who was 52, had enough of the business and wanted to retire. This was the start of the expansion. In 2017, 2018, 2020 and 2021 Pierre bought four more contracting businesses. He explained that he didn’t necessarily go looking to buy out these businesses, but that the opportunities arose for him.

Hamon runs six McHale Fusion balers and loves them.

“Each business was unique. I estimate that client retention from taking over another contractor was around 50-70%. I often see those customers who left return after two or three years. One thing I don’t do is get new customers based on price. Because these type of clients will leave you again for the next cheapest contractor.

“With the takeover of the other businesses, it became large enough to put management staff in place. We now are working out of six depots with a manager in each who essentially runs that smaller business.

“It's hard to quantify how much work we do each year. I estimate we are doing some jobs on 42,000ha".

“I have two staff who oversee three depots each. They are heavily involved in planning and logistics. They gather data and push data and technology on to farmers such as yield mapping and NIR systems.

“We have weather stations scattered all over the areas we work in. Weather data and rainfall are checked every morning before staff head off in the tractors, so we know we won’t be stopped up. We work in a 100km radius from our main yard and travel around 30km from each site for work, but sometimes we often go further. Annual rainfall within this radius can vary from 700mm to 1,100mm.

Customers

“We have 1,000 farmer customers on the books. Around 80% of our turnover is through 20% of our customers. The average customer farm size is 150ha but we have customers with holdings ranging from 1ha right up to 1,500ha, so we deal with all. The average field size we work is less than 3ha. Some 98-99% of our customers never change contractor – there is a great loyalty with most customers. Our average customer would cut 50ha of maize annually. The average farm in this region is around 150ha.

“It’s hard to quantify how much work we do each year. I estimate we are doing some jobs on 42,000ha. We combine around 10,000ha, plant and harvest 5,000ha of maize, spread 3,000ha of fertiliser and make 45,000 bales. I’m not sure how much grass we harvest as the foragers and the wagons are charged out on an hourly basis.

Staff

“We employ 61 full-time staff all of whom are French. This includes six office staff, six managers, two in planning and logistics and two mechanics, and 45 drivers. I also employ 10 part-time drivers. The majority of staff have been with me for years. I’d guess that over half the team have been with the business for over 10 years. I try to pay my staff well to keep them, I’d like to think I’m the best-paying contractor in the region.

“All staff are paid on an hourly basis. We use time sheets where everyone clocks in and clocks out. We will be moving to an app system shortly though.”

Machinery

Historically, the family has always operated John Deere tractors, but Fendt has made inroads in recent years. Pierre’s first experience with Fendt was through a contracting business he purchased. At the moment there are 110 self-propelled machines and around 200 trailed implements. In terms of tractors, there are 45 John Deeres and 20 Fendts. These range from 120hp up to 500hp including Fendt’s flagship 1050 Vario.

“We employ 61 full time staff.This includes six office staff, six managers, two in planning and logistics and two mechanics, and 45 drivers".

“Last year, we bought 14 new tractors, – 10 John Deeres and four Fendts. We try to keep the same drivers on the same tractor, but this isn’t always possible.

“We run all John Deere foragers, but I’m open to changing brands. I quite like the Krone. If I do change, I will probably buy four or five of that particular It’s important for me to have a stock of spare parts on the shelf. So, the more similarity in machines, the better. At the moment the fleet comprises eight 8000 series, one 9900i and three older 7000 series machines that are used for grass silage and as backup machines.”

In addition, the fleet is made up of 30 combines, six McHale Fusion balers, two self-propelled sprayers, one self-propelled beet harvester, 12 slurry tankers, 15 muck spreaders, 15 mowers (five butterflies, 10 trailed), 15 drills and three forage wagons.

Hamon estimates that he has €200,000 to €300,000 worth of parts in stock at any one time, and uses €1.5 million worth of parts annually.

“As the business has expanded so much each year, we don’t have a set policy of changing machines. We’ve had to keep most machines and just buy more. In the near future, I would like to see it getting to a stage where we change the tractors after five to seven years, and keep machines within warranty. Typically, our tractors would be doing 1,500 hours/year. This year we will replace a minimum number of machines due to rising costs and instead wait and see what happens next year.

Pierre uses the 'My John Deere' app - the picture shows where his JD machines were working at the time of our visit.

“When it comes to buying and upgrading machinery, it involves a conversation with the managers on what they need and what they want. We then negotiate the price with the dealer and go from there.”

Parts

Pierre has a very impressive stock of parts at his home base, and carries some stock of parts at his other depots. He estimates that he has €200,000 to €300,000 worth of parts in stock at any one time, and uses €1.5m worth of parts annually.

He tries to carry all major wearing parts in stock, along with having his own mechanics.

When it comes to repairs, he said a mechanic would typically cost €100 for a callout fee, and €80/hour thereafter, rising to €100/hour at the weekend. “We carry out 80% of the mechanical work ourselves, while diagnostic work is done by the dealers. In general, for buying parts, we work through a national buying group of contractors.”

Rates and invoicing

Like in New Zealand, mowers, rakes, wagons and foragers are all charged out on an hourly basis. Mowing with butterflies would cost you €220/hour, while a tri-axle wagon would cost €90/hour and then €104/load thereafter.

The roof of his most recently built machinery storage shed was fitted with solar panels.

Pushing up silage is all carried out with tractors, and not wheel loaders like is commonplace in Ireland. A tractor on the pit would cost up to €100/hour, depending on its size. Meanwhile, baling and wrapping with a fusion would cost you €16/bale. Slurry application through a Vervaet self-propelled tanker with a disc injector is priced at €210/hour.

Hamon has two full-time mechanics and carries out 80% of the mechanical work in-house.

“Invoices are sent out to customers at the end of every month. Some farmers will pay monthly but more will pay once a year. I honestly feel that my business is less profitable than a typical smaller contracting business. But I am looking to the future.”

Contracting in France

In France, the term agricultural contractor is pretty much unrecognised. It is instead given the name entrepreneur travel agriculture (ETA).

Hamon has weather stations scattered all over the areas he works.

“Through my previous role with John Deere I’ve visited many contractors all over Europe. No matter where you go, contracting is the same all over the world. Farmers want to know you; they want to have your mobile number and they want the best service possible at the lowest price. The average contractor in France would employ two to three drivers – in this area they are a little larger – they might employ 10 staff. In my area, you would have a CUMA group and two contractors typically within a 5km radius.

Staff training.

“The big downfall I see with contracting is that it’s a race to the bottom – who will be the last to die kind of a thing. When I decided to come home and take over the business, I wanted to set a new strategy, take a new approach.

“I set out a meeting with other large contractors in the region who I knew I could work with. I proposed that we change how we do business, we hire agronomists, we push precision agriculture and soil health.

The fleet includes 12 large slurry tankers and 15 muck spreaders.

“We wanted to be a step above the rest, and offer more to the farmers. So, we came together and set up a company.

“This has proved very successful. Our company is made up of 16/17 very good contractors, and between us we employ 450 drivers. We all continue to run our own businesses separately, but the company employs two full-time agronomists who offer advice to our farmers. The company also acts as a buyer group for parts and plastic, and has started carrying out tests for chemical company Bayer.

“CUMA, rather than another contractor, is my biggest competition, but I feel it's becoming less and less popular in this area".

“All of the contractors work in defined areas, which means we work hand in hand and help each other out when we are stuck.”

CUMA

Just down the road from Pierre’s yard is a large CUMA group. This particular CUMA group has its own workshop, several large machinery storage sheds and a serious fleet of kit – probably as much kit as you would spot in any Irish contractor’s yard.

"Our average customer would cut 50ha of maize annually. The average farm in this region is around 150ha”.

“CUMA, rather than another contractor, is my biggest competition, but I feel it’s becoming less and less popular in this area. The bigger farmers want a good professional service.

“I’ve found that some of the farmers who are involved in CUMA, generally don’t want to use a contractor anyway – there’s a lot of politics in it.”

GPS theft

Machinery theft is a problem everywhere, especially when it comes to GPS Pierre has endured a very difficult time with thieves stopping in on several occasions to steal John Deere GPS guidance systems, including both screens and receivers.

“We have 1,000 farmer customers on the books. Around 80% of our turnover is through 20% of our customers. The average customer farm size is 30ha-40ha".

“On the first occasion, thieves came into my yard at night and stole 15 John Deere guidance systems. They came a second time and stole eight more. In total this has cost me €100,000.

“The only way we can keep the systems safe is by taking them off every tractor every night, there’s no other solution at the moment.”

Brittany region

Brittany is region in the west of France. Pierre described it as having a Celtic culture.

France is eight times the size of Ireland, but to put it into perspective, Brittany is almost the size of Connacht and Leinster combined.

Brittany has a high concentration of livestock farming. For example, 55% of France’s cows and 60% of France’s pig farmers are in the Brittany region.

"We work in a 100km radius from our main yard and travel around 30km from each site for work, but sometimes we often go further"

The knock-on effect of this is that 72% of French contractors are also situated in the region, roughly totalling 1,500 contractors. The average price of land in the Brittany region is €15,000/ha.

The professionalism of the contracting business was really interesting. It was operated as a proper business. The way contracting businesses are bought and sold, with echoes of what we’ve previously reported from New Zealand, was also interesting.

The roof of Pierre’s most recently built machinery storage shed was fitted from top to bottom with solar panels. The power being generated is being sold back to the grid at 9.5c/unit, and is locked into a 20-year agreement.

While travelling through France, Peter Thomas Keaveney and Gary Abbott visited Hamon et Fils, Frances largest contractor who operates 65 tractors across six depots.

One thing that caught our attention when we visited was how some farmers approach the contractor. For example, Pierre was approached from a large farmer through LinkedIn while we were chatting to him – not something you’d see in Ireland. He didn’t blink as eyelid, and fully expected to be working for him next year following the approach.

Slurry application through a Vervaet self-propelled tanker with a disc injector in the region is priced at €210/hour.

SHARING OPTIONS