In 2006, Billy Lee established an ash plantation in part of his farm in the townland of Curraghgorm, a few miles west of Mitchelstown. The family farm was spread over a number of lots and ash was ideally suited for this section of the farm.

“I was a suckler farmer and as my farm was disjointed, I looked at ways to supplement my earnings and opted to plant some of my land with ash,” he says.

“For me, it was an investment but I also like trees. I make furniture from ash and alder as a hobby, as they are ideal species for woodwork.”

With this in mind, he planted 11.86ha of ash and broadleaves with approximately 15% retained for biodiversity such as hedgerows and streams.

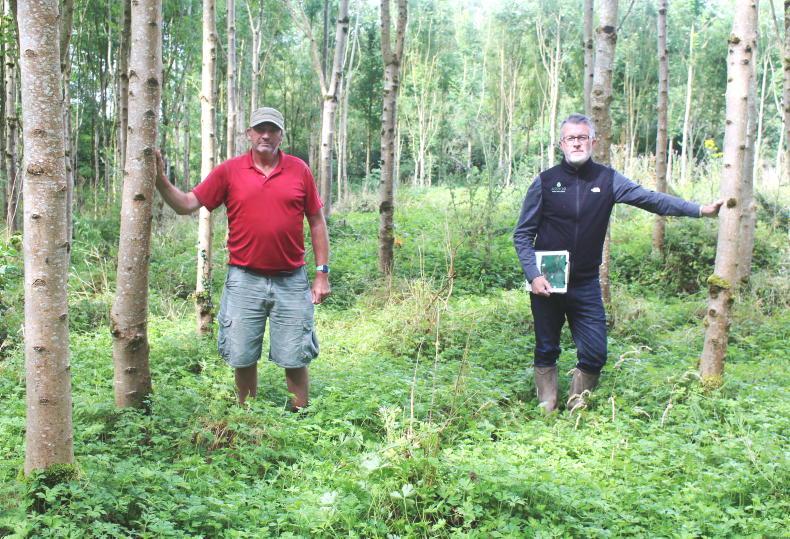

Now, 15 years later, surrounded by straight well-formed trees, his decision to plant ash seems like an ideal species selection, at first glance. Everywhere you look, the crop is extremely well-managed, with trees that appear healthy and within a few years of producing quality hurley ash.

But, when you look up, the unmistakable signs of ash dieback are everywhere. They are depressingly obvious as skeletal branches replace the once verdant canopy.

Despite the healthy looking lesion-free tree trunks, this carefully nurtured plantation is dying as a result of the deadly disease caused by the fungal pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus.

Billy Lee knew his woodland and his pension fund were first at risk in 2012, when ash dieback was detected in Ireland. He hoped that its spread would be slow, to give him time to cash in on at least some of his investment but the first signs of the disease were apparent a few years ago.

Now, he has no option but to remove all the ash and replant as soon as possible under the ash Reconstitution and Underplanting Scheme (RUS).

The RUS is totally inadequate for his needs as no compensation is provided, which rankles him because “the Department should bear responsibility for introducing the disease to Ireland,” he says.

“I would have liked to go back with broadleaves but there is no real alternative to ash so I have no choice but to opt for a commercial conifer crop.”

After discussions with John Roche, forester with Arbor Forest Management, they agreed to remove the ash and replant when the RUS was announced last year. The replacement crop will comprise 70% Sitka spruce, along with a mixture of broadleaves and open biodiverse unplanted areas. Any existing trees, other than ash, will be left in place.

Arbor applied for technical approval, on 31 July last year, to begin the reconstitution process. What happened next astounds Lee. “I was under the impression that the Department would help in every way possible just as their officials did in the past during an outbreak of TB in this area.”

He has had no offer of help from the Department inspectorate, but every possible obstacle has been placed in his and Arbor’s way in trying to salvage the ash and re-establish a crop that would provide some income in 15 to 20 years’ time.

Arbor waited six months before the Department even acknowledged its RUS application. Arbor submitted a detailed harvest plan in reply to a request last February and the Department outlined in May that “planning permission may be required” in addition to a felling licence as replacing “broadleaves with conifers is not ‘exempted development’”.

Although Arbor applied for 9.9ha under RUS, as only the ash needs to be removed, the Department said the site “exceeds 10ha” and the following would be required: “An “Environment Impact Statement (EIS) from the proposer and an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) undertaken by the local planning authority. Planning permission or a section 5 letter from the local planning authority is also required.”

Roche believes this area should be screened out for appropriate assessment (AA) as the site is level with a free-draining brown earth soil, so there is no danger of water runoff and no risk to the nearest hydrological link which is the River Blackwater SAC.

“This is 10.5km away and when plotted on iFORIS the actual hydrological distance is over 28km,” he says.

“As the treated area is under 10ha, a species change as envisaged should not require planning permission or an EIS which could cost the owner at least €10,000.”

Billy Lee and many other farmers planted ash which was strongly promoted by the Forest Service throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

The first major broadleaf afforestation programmes began in 2003, with ash the predominant species. Farmers bought into the scheme in hundreds as they understood ash as an important hedgerow and woodland species.

The sale of hurley ash butts between the ages of 25 to 35 years would have yielded an income of at least €620,000 for Billy Lee, based on 1,350 hurley butts per ha averaging €46 each.

Further income would be achieved for firewood and quality commercial furniture lengths before the crop reached its full rotation estimated at 60 years.

John Roche supported ash afforestation and would have encouraged clients to plant the species on suitable sites. He feels responsible now to help owners salvage their sites but says the Department has abdicated its responsibility by introducing an inadequate RUS and also referring environmentally sound reconstitution projects to local authorities for planning permission.

“Now, the Department plans to further penalise growers like Billy to produce an EIS when a felling and planting licence should be granted by Forest Service inspectors,” he says. “This example demonstrates that the Department has absolutely no empathy with the forester or the grower.”

Foresters criticise Department for abdicating its responsibility to ash growers

Foresters and ash woodland owners have heavily criticised the performance of the Department since ash dieback was detected in Ireland.

The Irish Farmers Journal contacted six foresters – three with forestry companies and three forestry consultants – all who have clients with ash dieback. They were all scathing, not only of the ash RUS but also of the way the Department and its inspectors were processing applications. Only one forester had received RUS approval.

In many instances, applications were being referred to county councils whose staff are asking why the Department can’t deal with this issue.

Silvicultural

Local authorities have neither foresters nor ecologists to adjudicate on what are essentially silvicultural issues.

This is not unique to the ash scheme but is bedevilling all aspects of the forestry programme. It highlights the need for a total revision of the regulatory system to allow forestry “move away from a licensing model to a regulatory model that does not require a fresh licence for every activity,” as proposed by Forest Industries Ireland (FII).

The current licensing system is unnecessary and is not replicated in other countries. Irish forestry needs a more sensible approach that can be both rigorous and efficient as FII have repeatedly pointed out.

The Department needs to accept the need for reform and begin the process of regulatory change.

It also needs to scrap the existing RUS and provide a new grant scheme, along with premium payments that reflect the huge financial losses incurred by ash growers who played no part in the introduction of the disease to Ireland.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: