It is just two years since I sent my first piece to the Irish Farmers Journal.

It was prompted by my concerns about the projected sea level rises associated with global warming and how the adoption of carbon farming could slow down the impending coastal and river flooding and moderate expected climate change.

It was then an outlier topic and fair play to the editors for publishing it. In the intervening two years, climate change has become a more mainstream issue and events have left a diminishing number of deniers on very shaky ground. We have just seen temperature records broken in four of the last six months, flooding events surpassing historical records and alarmingly high temperatures in the Arctic. It is no longer doomsday talk, it is our present and our future.

ASA Conference

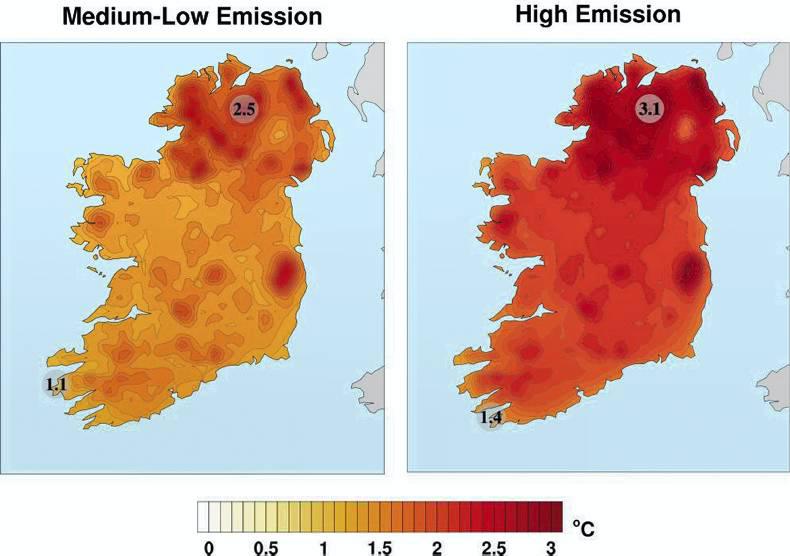

Last week I attended an ASA (Agricultural Science Association) conference on the effects of climate change on Irish farming. The most dramatic information came from Dr Paul Nolan, a climate scientist from the Irish Centre for High-End Computing. He ran a video illustrating how things will be over the next 30 years.

Two scenarios were presented. The first (low emissions) broadly aligns with a future where the decisions of last month’s COP21 Paris agreement to keep warming below 1.5°C/2°C actually succeeds.

The second (high emissions) aligns to a scenario where we keep on with business as usual, just tinkering around the edges. (An overview of his research can be found

In planning ahead, the prudent option is to hope that COP21 succeeds, but to assume that it won’t. We need to work with the worst-case scenario in mind. It is almost certain that by 2050 we will see average summer temperature increases of 2°C to 3°C, a 50% reduction in frost days, increasingly severe storms, less rain in spring and summer and more extreme rainfall events in autumn and winter.

Adapting will present challenges, however. I personally believe that our biggest challenges are likely to come from the sea. Rising sea levels of up to half a metre along with high-energy storm events will breach coastal defences and erode coastal lands, which along with the knock-on effects on streams and rivers, will result in the loss of thousands of hectares of Irish farmland.

The role of ruminants

As outlined in my piece of two years ago, carbon farming is a tried and tested concept to delay and moderate the oncoming effects. Sequestering the existing excess of atmospheric carbon is just as urgent as controlling future emissions.

There must be a twin-track approach.

At the ASA conference, one speaker, in explaining emissions, equated a cow with two family cars, ignoring the old knowledge that soil organic matter cannot be increased without ruminants and that increasing soil organic matter is a highly effective method of sequestering carbon.

Putting two cars on a ha of grass will never sequester one gramme of carbon, whereas putting two cows on a ha of grass will increase soil organic matter by 1% per annum, thus sequestering significant amounts of carbon. We should stop allowing cows to be equated with cars. It is nonsense.

Policy, advice and the market supports

In conclusion, carbon can be quickly sequestered on our farms by carbon farming.

This simply involves building up soil organic matter using ruminants and growing more woody perennial shrubs and trees. Farmers know how to build organic matter but require cattle and sheep and policy and market support for grass-fed meat to do it.

Farmers can maintain more trees and shrubs on farms but need the Department of Agriculture and local councils to stop forcing their removal and adopt policy that supports Agroforestry. Farmers can and will adapt, but policy, advice and external support has a great deal of catching up to do.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: