What is now the Irish Farmers Journal was founded in 1948 as a monthly magazine called the Young Farmers Journal. Produced by Macra na Feirme and with Macra founder Stephen Cullinan as editor, the first eight-page edition was published on 1 July 1948, costing 2p. The content focused on educational articles on practical ways to improve your farm.

By January 1950, the magazine was thriving and being sold to farmers across Ireland and internationally. Now renamed the Irish Farmers Journal, the publication moved to a weekly print run but struggled financially. It was sold by Macra to the Fleet Printing Company, which cut it back to fortnightly editions.

In 1951, as chair of Macra na Feirme, John Mooney brought a proposal to PaddyO’Keeffe to purchase the Irish Farmers Journal.

Enter John Mooney, Macra chair, who joined forces with Paddy O’Keeffe and Michael Dillon, to buy back the paper from the Fleet Printing Company for £2,000.

Mooney invested £10,000, all of which was lost in the first year. But by 1952, the ship had been turned and by 1954, 18,000 copies a week were being sold.

The National Farmers’ Association, later the Irish Farmers Association, was founded on 6 January 1955, with close links to the paper.

Meanwhile, rural electrification changed farms and farmhouses across Ireland, bringing with it milking machines, water pumps and other labour-saving devices.

TK Whitaker’s 1958 economic report led to the Programme for Economic Expansion, with £14m allocated for agriculture across five years.

The same year An Foras Talúntais, later Teagasc, was established for agricultural research.

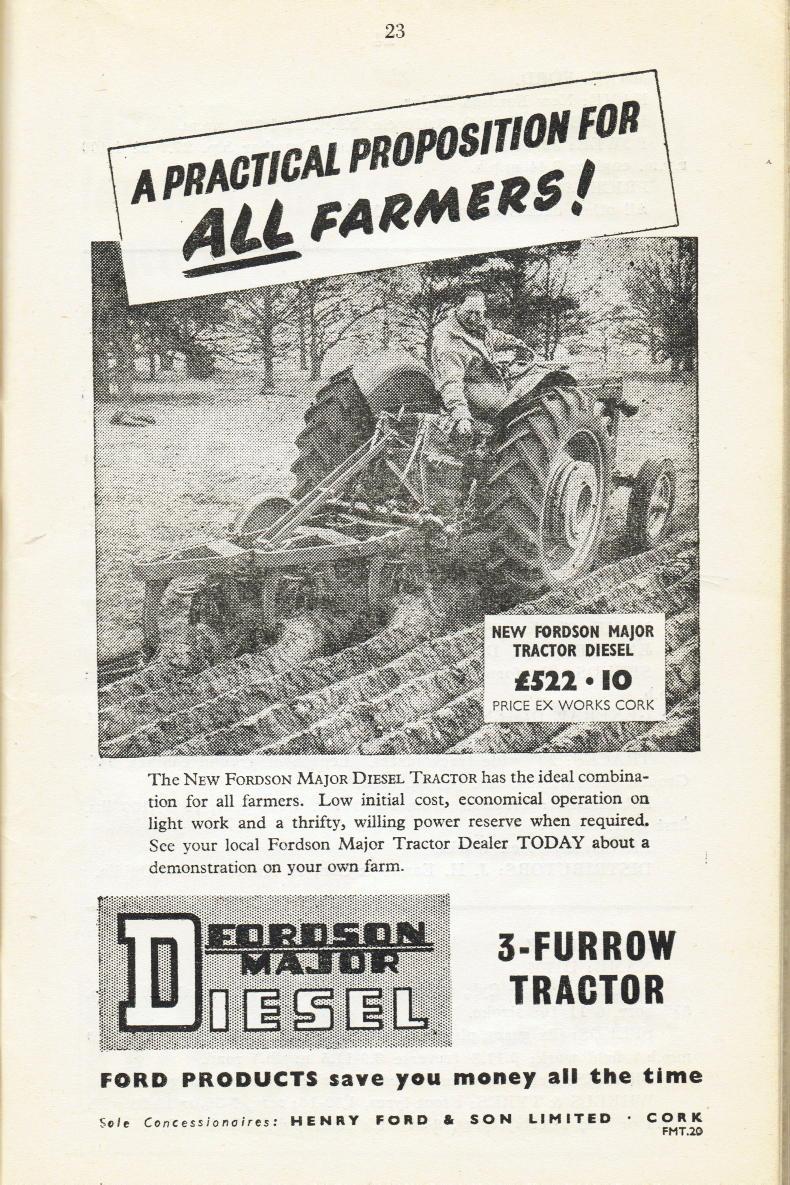

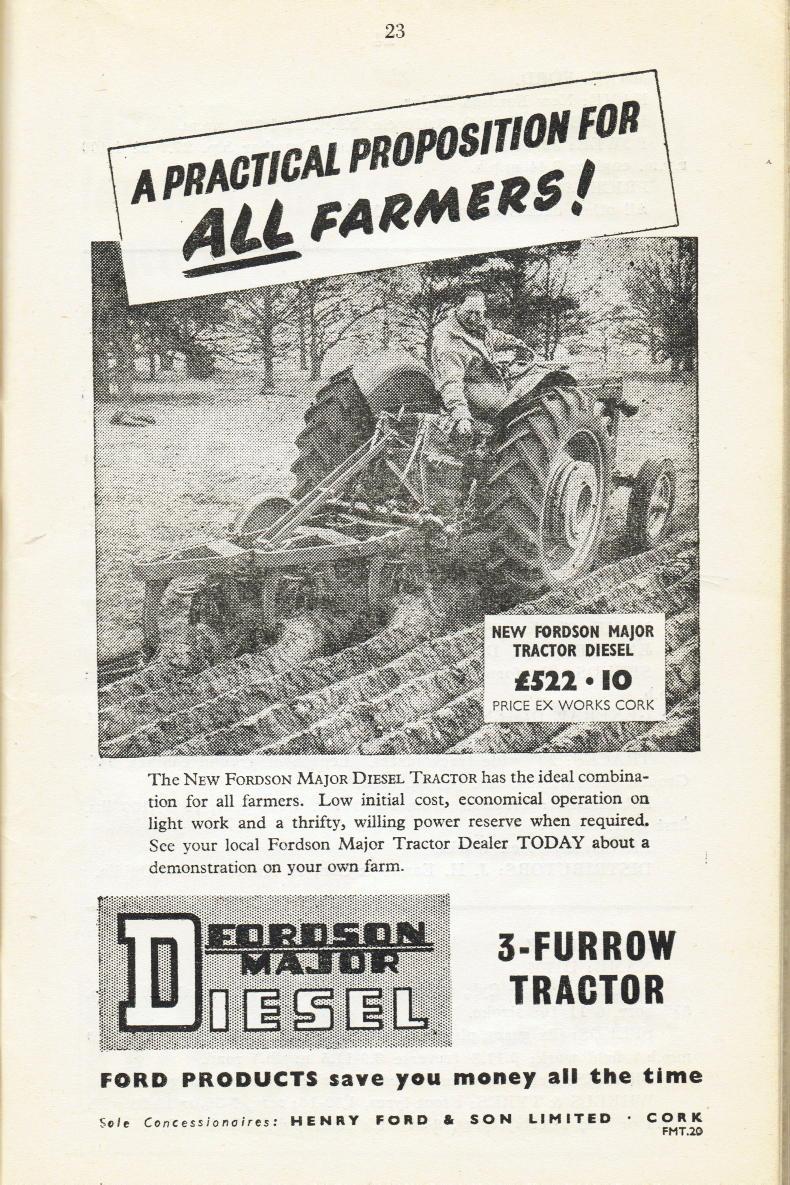

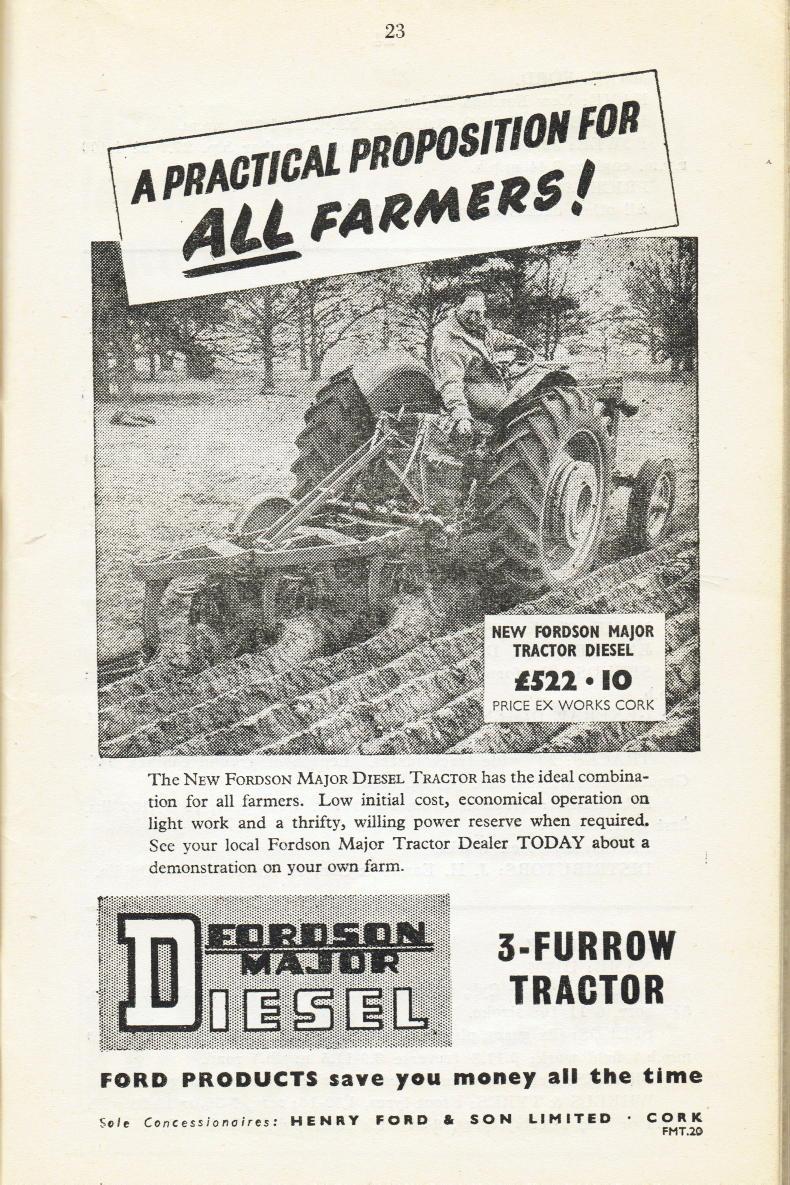

This shows a Fordson Major advert from the Farm Machinery Guide 1954, where Ford was selling the tractor as a three-furrow tractor and price was competitive at £522.10.

In the early 1960s, foreign cattle breeds – Charolais and Herefords – were imported for trials to improve Irish beef. They were followed 10 years later by the first Holsteins from Canada.

During the 1960s, writers in the Journal included poet and novelist Patrick Kavanagh and playwright John B Keane.

It was during this time that John Mooney was offered £100,000 to sell the paper to Thompson Group, publishers of the London Times. He turned the offer down and set up the Agricultural Trust in 1965, which still owns the Journal and its sister publications today.

All profits earned by the Journal would be reinvested, through the trust, into editorial content and other agricultural initiatives.

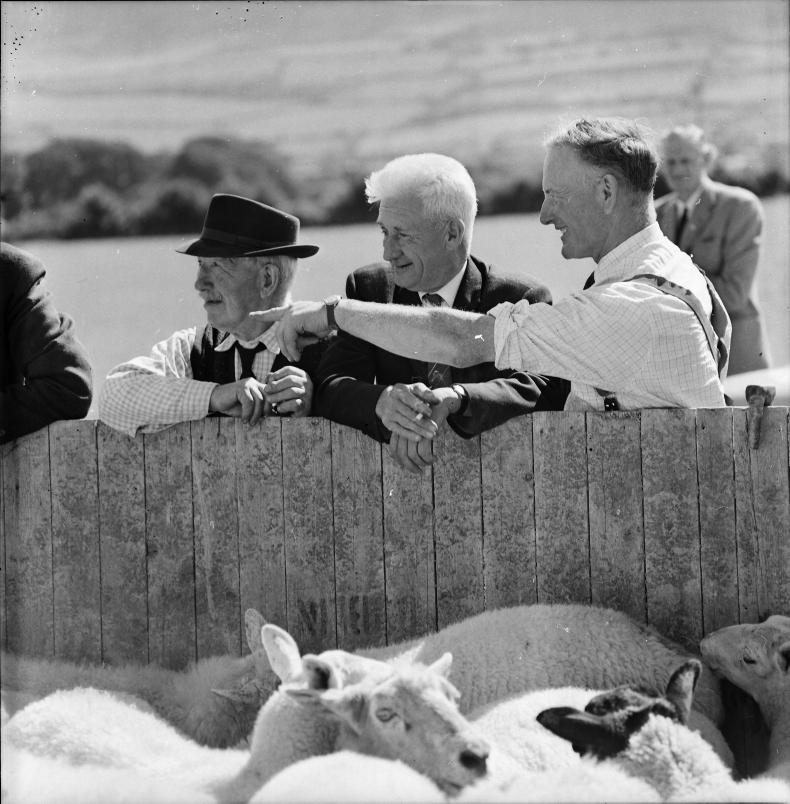

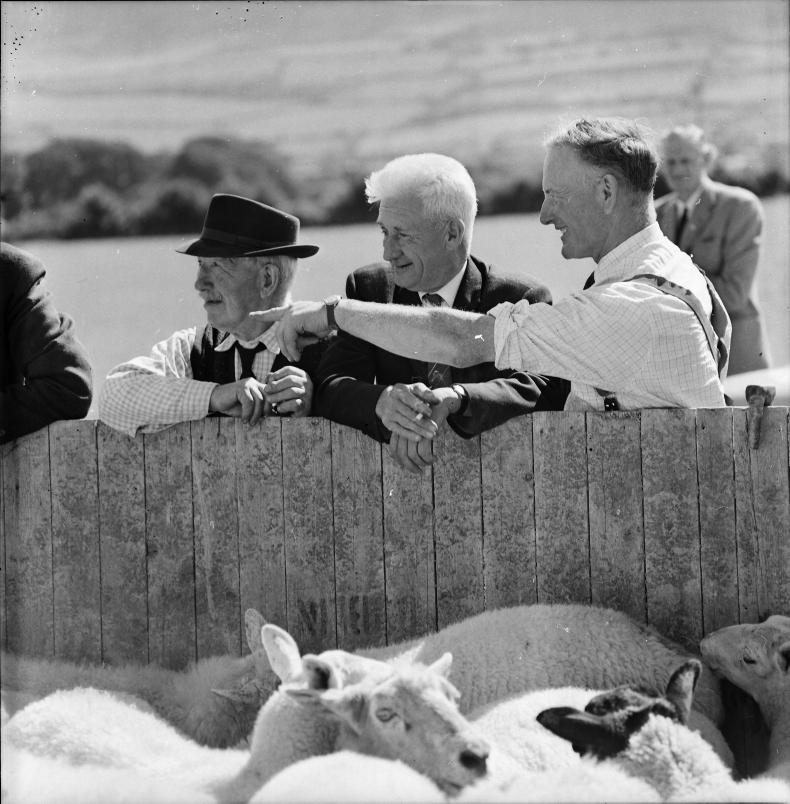

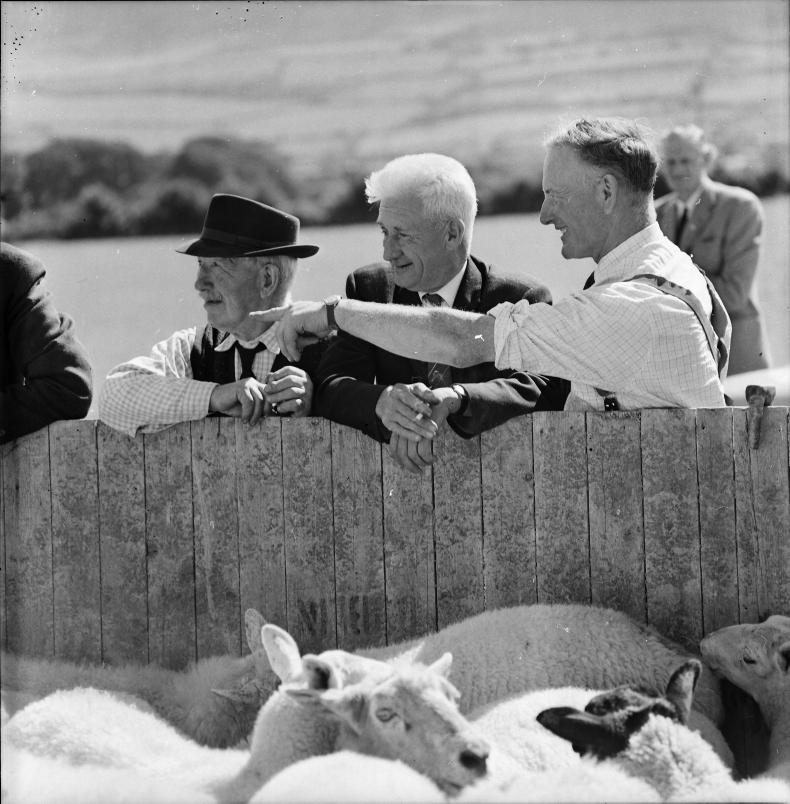

Farmers at the Macra field day, Tallaght, Co Dublin, on 30 August 1964. \ IFJ Archive

The Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement was signed in 1965, allowing unrestricted access for Irish agricultural produce to the British market.

The October 1966 Farmers Rights protest march over income supports saw Rickard Deasy lead farmers from Bantry to Dublin and into a 21-day sit-in at Government buildings. By March 1967, more than 60 farmers had been jailed in the bitter row. They were released from Mountjoy on condition they would end illegal activities such as road blocking and non-payment of rates.

The 1970s began with a coming together of the NFA with other sectoral farm organisations, including those representing beet and horticulture growers and regional milk producers to form a new organisation: the Irish Farmers Association.

The move was welcomed in the Journal as one that would bring strength from unity.

The NFA and the Journal were instrumental in setting up Farm Business Developments (FBD) in 1970, providing farmers with insurance.

Construction of the Irish Farm Centre in Bluebell, Dublin 12, began in 1970, and the building was officially opened by Taoiseach Jack Lynch in 1972.

The Irish Farm Centre on the Naas road was officially opened in 1972. \ Irish Farmers Journal archive

Circulation of the Journal exceeded 70,000 copies per week.

Joining the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973 gave Irish farmers access to the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) and decades of important supports.

One of these, the Farm Modernisation Scheme provided grants for improving buildings, equipment and more.

It also opened the door to headage payments for livestock from 1975, followed by drainage schemes, ewe and suckler cow premia, afforestation grants and more in the years that followed. Farm output and farm incomes rose.

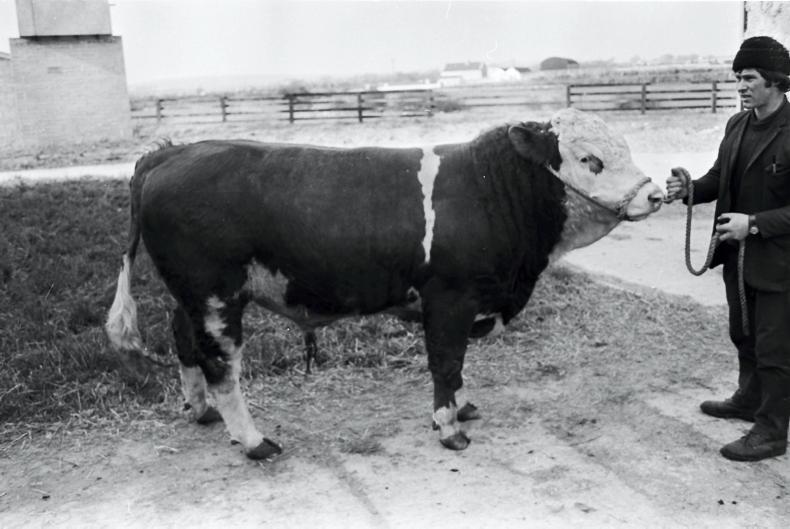

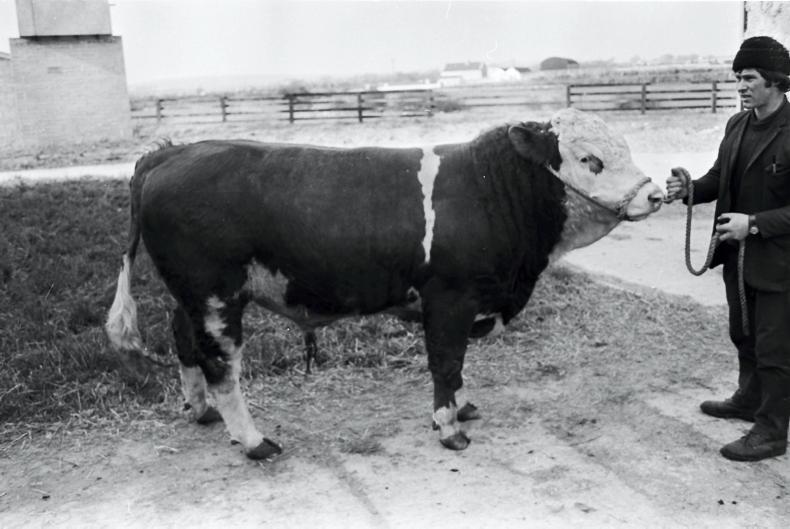

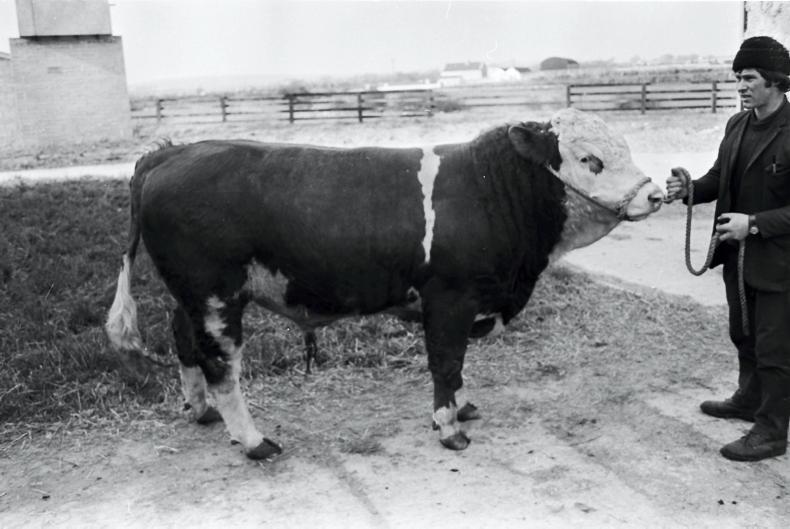

A bull at stud in Tully, 1976. \ John Shirley, Irish Farmers Journal archive

Taoiseach Charlie Haughey’s made his infamously ironic declaration that “we are living way beyond our means” in January 1980 and the following decade was one of massive unemployment and emigration.

On farms, incomes fell below the 1960s

Over 400,000 people emigrated, many from farms, with grim austerity for those who remained.

On farms, incomes fell below the 1960s. In 1985, the average family farm income was £94 per week. Mass farmer protests were held in Limerick and Dublin.

Intervention prices for farm produce since joining the EEC saw overproduction of commodities grow into what became known as butter and beef mountains, and milk lakes.

April 1984 saw a milk superlevy introduced, whereby each country was allocated a milk quota and any milk above this levy would be penalised financially.

Inside the Irish Farmers Journal, the Farm Home pullout segment aimed to appeal to the wider farm family and featured favourites such as columnist Liz Kavanagh and the still-running ‘Getting in Touch’ column. In 1986, this was relaunched as the magazine

Paddy O’Keeffe retired in 1988 after 37 years as editor, to be succeeded by Matt Dempsey.

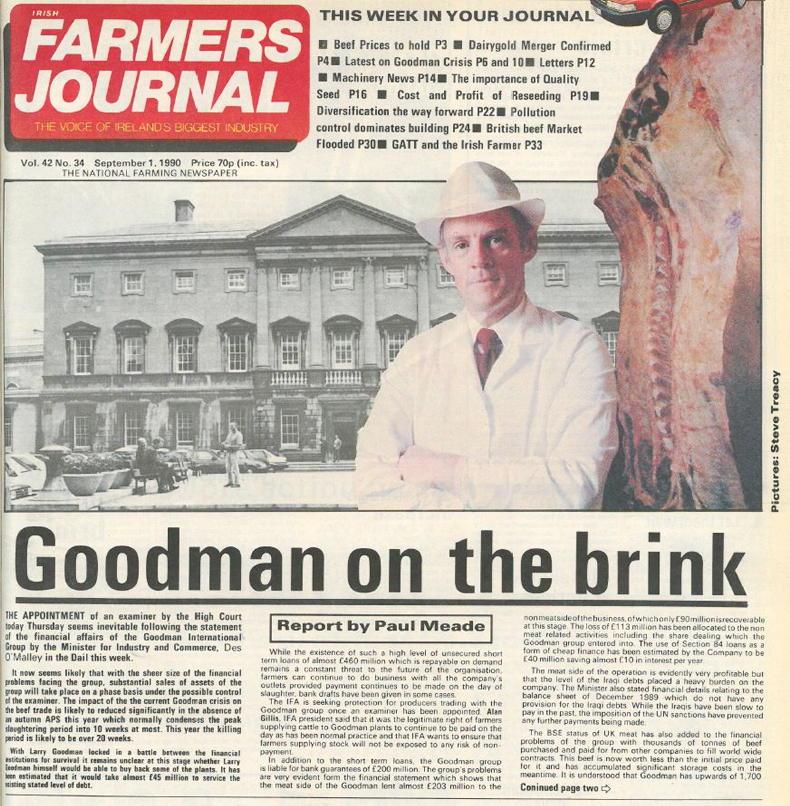

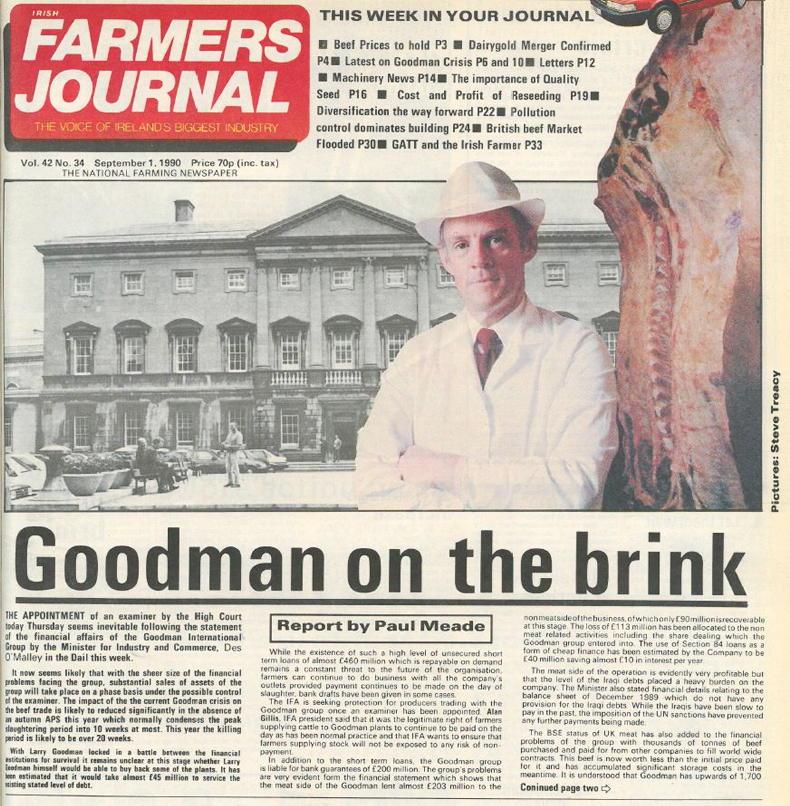

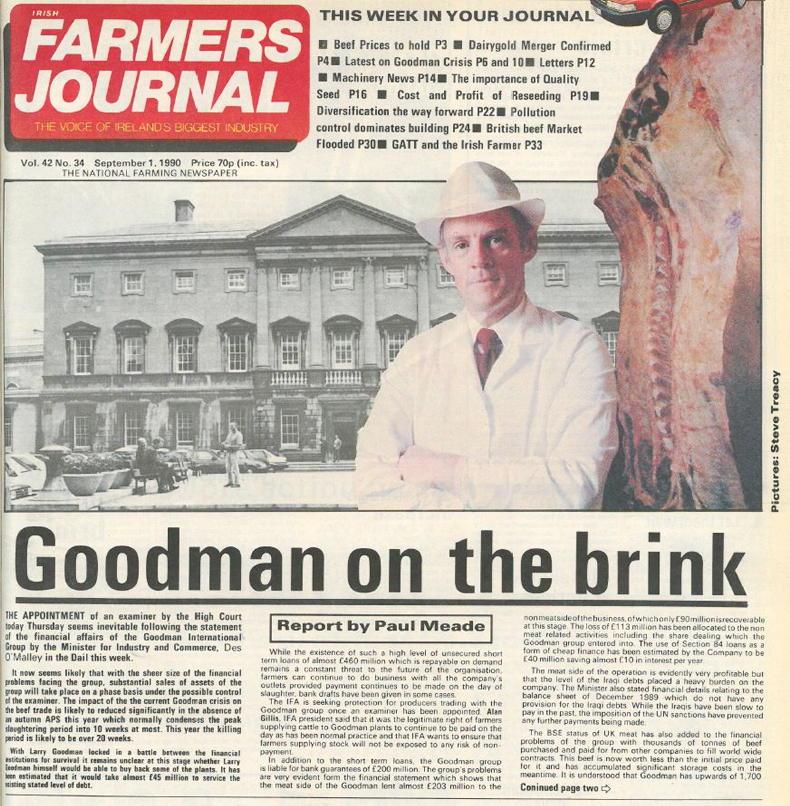

“Goodman on the brink” declared the Irish Farmers Journal’s front page in September 1990.

The Government rushed through emergency legislation to allow the Goodman International Group enter examinership. Larry Goodman, the biggest processor and exporter of beef in Europe, was owed £170m by Saddam Hussein’s government when Iraq invaded Kuwait and was subject to UN sanctions.

The Irish Farmers Journal’s front page on 1 September 1990 as Larry Goodman’s companies went into examinership.

The Beef Tribunal in 1991 was set up to investigate allegations of illegal activities, fraud and malpractice in beef processing after claims made in a BBC World in Action documentary of serious irregularities in Larry Goodman’s empire.

The tribunal confirmed that tax evasion had occurred and also revealed close links between Goodman and government figures.

Ray MacSharry’s Agenda 2000 reform of the CAP saw agricultural policy move away from food market supports and guaranteed prices

Goodman later managed to buy back his business.

Ray MacSharry’s Agenda 2000 reform of the CAP saw agricultural policy move away from food market supports and guaranteed prices, and towards direct payments to farmers to compensate for the resulting fall in produce prices.

Suckler cow payments, two-stage special beef premia for male cattle over 10 and 22 months of age and slaughter premia were introduced.

So too were ewe premia, area aid payments for tillage crops and compulsory set-aside areas. The bureaucracy required of Irish farming increased massively with the arrival of the “cheque in the post”.

BSE scare

On 23 March 1996, the BSE scare erupted when British authorities linked the bovine neurological disorder bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) or “mad cow disease” to the deadly human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Meat and bone meal fed to cattle was the cause, and demand for beef collapsed as consumers switched to other meats.

The Irish factory kill in one week fell from 30,000 to 10,000 animals.

Outside the farm gate, Ireland’s economy began to boom, as funding from Europe and multinational investment drove the jobs market and incomes.

The agricultural sector began to play a lesser role in the overall national economy and the availability of better paid off-farm work saw part-time farming increase. In 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was signed and the Celtic Tiger had begun to roar.

New technologies

A 1996 Agricultural Trust meeting noted that the “new technologies such as fax, internet and email would impact significantly on how commercial farmers could have and might want instant information” and a wider appeal would be needed to maintain circulation.

In 1998, in its 50th year, the Irish Farmers Journal launched its website, noting that its aim was “to make the Journal’s electronic edition the source of agricultural and rural information on the Internet which means that the information will be updated weekly”.

The 21st century opened for farmers with the dramatic resignation of the entire leadership of the IFA.

A seven-day IFA blockade of meat factories had seen meat processors secure an injunction against the organisation to end the blockade or face a £500,000/day penalty.

The resignation of the IFA top brass, led by Tom Parlon, meant they could not be held legally responsible for any further action taken as individual farmers.

Parlon went on to enter politics with the Progressive Democrats but, in 2007, having failed to win re-election he turned down a Seanad seat to become director general of the Construction Industry Federation (CIF).

Between 2000 and 2007, economic growth in Ireland was the highest of any EU member state

It wasn’t the only way in which property and farming crossed paths in the 2000s.

Between 2000 and 2007, economic growth in Ireland was the highest of any EU member state.

Property became the focus of the economy, with farmers with land on the outskirts of towns being wooed by property developers with colossal sums far in excess of its agricultural value.

Part-time farming increased as more farmers needed to secure additional income above what their farm output could provide.

Some left farming completely. By 2010, there were 139,829 farms in Ireland, down from 171,000 in 1991.

Inside the Irish Farmers Journal, two major issues dominated the pages for many months.

On 22 March 2001, foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) was confirmed in the Republic of Ireland for the first time in 60 years.

FMD had earlier been confirmed in Britain on 20 February and the first case in Co Louth was linked back to sheep imported to Northern Ireland and for slaughter in Athleague, Co Roscommon.

Severe restrictions on all farm movements were imposed, livestock on and surrounding the Jenkinstown, Co Louth, farm were culled.

The St Patrick’s Day Festival in Dublin was cancelled and Six Nations rugby and racing were cancelled north and south as part of an all-island effort to prevent FMD spreading. Across the water in Britain, over 6m animals were culled.

Eighteen years on, Irish farmers are still wary of Brazilian imports into the EU, with environmental standards the major point of difference.

Brazilian beef was the other major farming issue dominating pages.

In 2006, Irish Farmers Journal livestock editor Justin McCarthy and the IFA’s Kevin Kinsella and John Bryan travelled to Brazil to document its beef production systems.

Armed with photos and accounts that showed blatant discrepancies between the regulatory demands that EU farmers were required to meet and the standards of Brazilian production, they succeeded in getting EU-wide beef importation regulations fundamentally changed.

The collapse of the Celtic Tiger saw Ireland surrender its economic sovereignty to the infamous Troika of the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and the European Commission. While much of the economy remained in the doldrums for years, the agricultural industry powered on.

In 2013, Ireland – and subsequently all of Europe – was rocked by the discovery by the Food Safety Authority of Ireland, of equine DNA in what should have been beef burgers.

The discovery of horsemeat in beef burgers uncovered a Europe-wide food fraud problem.

Investigations revealed international food fraud on a massive scale, in which blocks of meat purporting to be beef but containing cheaper horsemeat and more, were traded between companies and countries.

Multiple meat traders were jailed in the following years, while Ireland’s food safety standards were subsequently recognised as some of the best in the world.

Milk quotas

The lifting of milk quotas in 2015 saw the production shackles removed from farmers all over Ireland.

Parties were held in pubs, sheds and milking parlours as the opportunity to increase cow numbers and therefore farm incomes was realised.

Milk processors planned for the surge in milk supplies as many beef and tillage farms converted to dairy as the wave of ‘new entrant’ farmers grew.

Later the same year, the IFA was rocked by scandal of its own when the pay of its top executive Pat Smith was revealed.

Both Smith and then-IFA president Eddie Downey resigned, with Smith later taking the IFA to court and being awarded €1.9m plus legal fees. Joe Healy was elected as IFA president in early 2016, and widely regarded as the “new broom” the organisation needed following the crisis.

Brexit

A year later, the Brexit referendum on 23 June 2016 saw editorial staff in all publications including the Irish Farmers Journal scrambling to assess the impact of Britain leaving the European Union.

Britain’s exit from the European Union had huge implications for the island of Ireland.

The detachment of Britain, Ireland’s biggest beef customer, from the EU, and Northern Ireland’s unique political and geographical situation made Brexit a real live problem for farmers all across the island.

Beef factory protests again hit the headlines in 2019, prompted this time by a fledgling farmer group called the Beef Plan Movement. Weeks of acrimony over beef prices and factory gate protests saw cattle and sheep processing severely restricted nationwide and eventually led to meat processors issuing High Court injunctions against individual farmers.

The IFA stepped in to defend the farmers in court, and last-ditch talks saw a beef forum established to resolve some of the issues angering farmers.

2020-2023: Covid-19 years

First reported in Wuhan, China, a few months earlier, COVID-19 arrived in Ireland in early 2020.

The novel coronavirus caused the death of almost 7m people worldwide and over 9,000 people in Ireland.

COVID-19 moved marts online and changed farming dramatically.

People were plunged into national and regional lockdowns aimed at reducing the spread and “flattening the curve” of the disease.

The toll on mental health for people and families affected is still being counted.

In a farming context, the pandemic rules turned everything upside down.

Even today the news pages of the publication are digitally delivered from Belmullet, Co Mayo

While farmers were considered essential workers and so less restricted than most, all farming business and social outlets were changed.

Marts moved online, co-ops switched to click and collect, pubs closed, and GAA matches and almost everything else was cancelled in lockdown.

Inside the Irish Farmers Journal, remote working became the norm overnight and even today the news pages of the publication are digitally delivered to the printers from Belmullet, Co Mayo, rather than the Irish Farm Centre in Dublin.

What is now the Irish Farmers Journal was founded in 1948 as a monthly magazine called the Young Farmers Journal. Produced by Macra na Feirme and with Macra founder Stephen Cullinan as editor, the first eight-page edition was published on 1 July 1948, costing 2p. The content focused on educational articles on practical ways to improve your farm.

By January 1950, the magazine was thriving and being sold to farmers across Ireland and internationally. Now renamed the Irish Farmers Journal, the publication moved to a weekly print run but struggled financially. It was sold by Macra to the Fleet Printing Company, which cut it back to fortnightly editions.

In 1951, as chair of Macra na Feirme, John Mooney brought a proposal to PaddyO’Keeffe to purchase the Irish Farmers Journal.

Enter John Mooney, Macra chair, who joined forces with Paddy O’Keeffe and Michael Dillon, to buy back the paper from the Fleet Printing Company for £2,000.

Mooney invested £10,000, all of which was lost in the first year. But by 1952, the ship had been turned and by 1954, 18,000 copies a week were being sold.

The National Farmers’ Association, later the Irish Farmers Association, was founded on 6 January 1955, with close links to the paper.

Meanwhile, rural electrification changed farms and farmhouses across Ireland, bringing with it milking machines, water pumps and other labour-saving devices.

TK Whitaker’s 1958 economic report led to the Programme for Economic Expansion, with £14m allocated for agriculture across five years.

The same year An Foras Talúntais, later Teagasc, was established for agricultural research.

This shows a Fordson Major advert from the Farm Machinery Guide 1954, where Ford was selling the tractor as a three-furrow tractor and price was competitive at £522.10.

In the early 1960s, foreign cattle breeds – Charolais and Herefords – were imported for trials to improve Irish beef. They were followed 10 years later by the first Holsteins from Canada.

During the 1960s, writers in the Journal included poet and novelist Patrick Kavanagh and playwright John B Keane.

It was during this time that John Mooney was offered £100,000 to sell the paper to Thompson Group, publishers of the London Times. He turned the offer down and set up the Agricultural Trust in 1965, which still owns the Journal and its sister publications today.

All profits earned by the Journal would be reinvested, through the trust, into editorial content and other agricultural initiatives.

Farmers at the Macra field day, Tallaght, Co Dublin, on 30 August 1964. \ IFJ Archive

The Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement was signed in 1965, allowing unrestricted access for Irish agricultural produce to the British market.

The October 1966 Farmers Rights protest march over income supports saw Rickard Deasy lead farmers from Bantry to Dublin and into a 21-day sit-in at Government buildings. By March 1967, more than 60 farmers had been jailed in the bitter row. They were released from Mountjoy on condition they would end illegal activities such as road blocking and non-payment of rates.

The 1970s began with a coming together of the NFA with other sectoral farm organisations, including those representing beet and horticulture growers and regional milk producers to form a new organisation: the Irish Farmers Association.

The move was welcomed in the Journal as one that would bring strength from unity.

The NFA and the Journal were instrumental in setting up Farm Business Developments (FBD) in 1970, providing farmers with insurance.

Construction of the Irish Farm Centre in Bluebell, Dublin 12, began in 1970, and the building was officially opened by Taoiseach Jack Lynch in 1972.

The Irish Farm Centre on the Naas road was officially opened in 1972. \ Irish Farmers Journal archive

Circulation of the Journal exceeded 70,000 copies per week.

Joining the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973 gave Irish farmers access to the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) and decades of important supports.

One of these, the Farm Modernisation Scheme provided grants for improving buildings, equipment and more.

It also opened the door to headage payments for livestock from 1975, followed by drainage schemes, ewe and suckler cow premia, afforestation grants and more in the years that followed. Farm output and farm incomes rose.

A bull at stud in Tully, 1976. \ John Shirley, Irish Farmers Journal archive

Taoiseach Charlie Haughey’s made his infamously ironic declaration that “we are living way beyond our means” in January 1980 and the following decade was one of massive unemployment and emigration.

On farms, incomes fell below the 1960s

Over 400,000 people emigrated, many from farms, with grim austerity for those who remained.

On farms, incomes fell below the 1960s. In 1985, the average family farm income was £94 per week. Mass farmer protests were held in Limerick and Dublin.

Intervention prices for farm produce since joining the EEC saw overproduction of commodities grow into what became known as butter and beef mountains, and milk lakes.

April 1984 saw a milk superlevy introduced, whereby each country was allocated a milk quota and any milk above this levy would be penalised financially.

Inside the Irish Farmers Journal, the Farm Home pullout segment aimed to appeal to the wider farm family and featured favourites such as columnist Liz Kavanagh and the still-running ‘Getting in Touch’ column. In 1986, this was relaunched as the magazine

Paddy O’Keeffe retired in 1988 after 37 years as editor, to be succeeded by Matt Dempsey.

“Goodman on the brink” declared the Irish Farmers Journal’s front page in September 1990.

The Government rushed through emergency legislation to allow the Goodman International Group enter examinership. Larry Goodman, the biggest processor and exporter of beef in Europe, was owed £170m by Saddam Hussein’s government when Iraq invaded Kuwait and was subject to UN sanctions.

The Irish Farmers Journal’s front page on 1 September 1990 as Larry Goodman’s companies went into examinership.

The Beef Tribunal in 1991 was set up to investigate allegations of illegal activities, fraud and malpractice in beef processing after claims made in a BBC World in Action documentary of serious irregularities in Larry Goodman’s empire.

The tribunal confirmed that tax evasion had occurred and also revealed close links between Goodman and government figures.

Ray MacSharry’s Agenda 2000 reform of the CAP saw agricultural policy move away from food market supports and guaranteed prices

Goodman later managed to buy back his business.

Ray MacSharry’s Agenda 2000 reform of the CAP saw agricultural policy move away from food market supports and guaranteed prices, and towards direct payments to farmers to compensate for the resulting fall in produce prices.

Suckler cow payments, two-stage special beef premia for male cattle over 10 and 22 months of age and slaughter premia were introduced.

So too were ewe premia, area aid payments for tillage crops and compulsory set-aside areas. The bureaucracy required of Irish farming increased massively with the arrival of the “cheque in the post”.

BSE scare

On 23 March 1996, the BSE scare erupted when British authorities linked the bovine neurological disorder bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) or “mad cow disease” to the deadly human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Meat and bone meal fed to cattle was the cause, and demand for beef collapsed as consumers switched to other meats.

The Irish factory kill in one week fell from 30,000 to 10,000 animals.

Outside the farm gate, Ireland’s economy began to boom, as funding from Europe and multinational investment drove the jobs market and incomes.

The agricultural sector began to play a lesser role in the overall national economy and the availability of better paid off-farm work saw part-time farming increase. In 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was signed and the Celtic Tiger had begun to roar.

New technologies

A 1996 Agricultural Trust meeting noted that the “new technologies such as fax, internet and email would impact significantly on how commercial farmers could have and might want instant information” and a wider appeal would be needed to maintain circulation.

In 1998, in its 50th year, the Irish Farmers Journal launched its website, noting that its aim was “to make the Journal’s electronic edition the source of agricultural and rural information on the Internet which means that the information will be updated weekly”.

The 21st century opened for farmers with the dramatic resignation of the entire leadership of the IFA.

A seven-day IFA blockade of meat factories had seen meat processors secure an injunction against the organisation to end the blockade or face a £500,000/day penalty.

The resignation of the IFA top brass, led by Tom Parlon, meant they could not be held legally responsible for any further action taken as individual farmers.

Parlon went on to enter politics with the Progressive Democrats but, in 2007, having failed to win re-election he turned down a Seanad seat to become director general of the Construction Industry Federation (CIF).

Between 2000 and 2007, economic growth in Ireland was the highest of any EU member state

It wasn’t the only way in which property and farming crossed paths in the 2000s.

Between 2000 and 2007, economic growth in Ireland was the highest of any EU member state.

Property became the focus of the economy, with farmers with land on the outskirts of towns being wooed by property developers with colossal sums far in excess of its agricultural value.

Part-time farming increased as more farmers needed to secure additional income above what their farm output could provide.

Some left farming completely. By 2010, there were 139,829 farms in Ireland, down from 171,000 in 1991.

Inside the Irish Farmers Journal, two major issues dominated the pages for many months.

On 22 March 2001, foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) was confirmed in the Republic of Ireland for the first time in 60 years.

FMD had earlier been confirmed in Britain on 20 February and the first case in Co Louth was linked back to sheep imported to Northern Ireland and for slaughter in Athleague, Co Roscommon.

Severe restrictions on all farm movements were imposed, livestock on and surrounding the Jenkinstown, Co Louth, farm were culled.

The St Patrick’s Day Festival in Dublin was cancelled and Six Nations rugby and racing were cancelled north and south as part of an all-island effort to prevent FMD spreading. Across the water in Britain, over 6m animals were culled.

Eighteen years on, Irish farmers are still wary of Brazilian imports into the EU, with environmental standards the major point of difference.

Brazilian beef was the other major farming issue dominating pages.

In 2006, Irish Farmers Journal livestock editor Justin McCarthy and the IFA’s Kevin Kinsella and John Bryan travelled to Brazil to document its beef production systems.

Armed with photos and accounts that showed blatant discrepancies between the regulatory demands that EU farmers were required to meet and the standards of Brazilian production, they succeeded in getting EU-wide beef importation regulations fundamentally changed.

The collapse of the Celtic Tiger saw Ireland surrender its economic sovereignty to the infamous Troika of the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and the European Commission. While much of the economy remained in the doldrums for years, the agricultural industry powered on.

In 2013, Ireland – and subsequently all of Europe – was rocked by the discovery by the Food Safety Authority of Ireland, of equine DNA in what should have been beef burgers.

The discovery of horsemeat in beef burgers uncovered a Europe-wide food fraud problem.

Investigations revealed international food fraud on a massive scale, in which blocks of meat purporting to be beef but containing cheaper horsemeat and more, were traded between companies and countries.

Multiple meat traders were jailed in the following years, while Ireland’s food safety standards were subsequently recognised as some of the best in the world.

Milk quotas

The lifting of milk quotas in 2015 saw the production shackles removed from farmers all over Ireland.

Parties were held in pubs, sheds and milking parlours as the opportunity to increase cow numbers and therefore farm incomes was realised.

Milk processors planned for the surge in milk supplies as many beef and tillage farms converted to dairy as the wave of ‘new entrant’ farmers grew.

Later the same year, the IFA was rocked by scandal of its own when the pay of its top executive Pat Smith was revealed.

Both Smith and then-IFA president Eddie Downey resigned, with Smith later taking the IFA to court and being awarded €1.9m plus legal fees. Joe Healy was elected as IFA president in early 2016, and widely regarded as the “new broom” the organisation needed following the crisis.

Brexit

A year later, the Brexit referendum on 23 June 2016 saw editorial staff in all publications including the Irish Farmers Journal scrambling to assess the impact of Britain leaving the European Union.

Britain’s exit from the European Union had huge implications for the island of Ireland.

The detachment of Britain, Ireland’s biggest beef customer, from the EU, and Northern Ireland’s unique political and geographical situation made Brexit a real live problem for farmers all across the island.

Beef factory protests again hit the headlines in 2019, prompted this time by a fledgling farmer group called the Beef Plan Movement. Weeks of acrimony over beef prices and factory gate protests saw cattle and sheep processing severely restricted nationwide and eventually led to meat processors issuing High Court injunctions against individual farmers.

The IFA stepped in to defend the farmers in court, and last-ditch talks saw a beef forum established to resolve some of the issues angering farmers.

2020-2023: Covid-19 years

First reported in Wuhan, China, a few months earlier, COVID-19 arrived in Ireland in early 2020.

The novel coronavirus caused the death of almost 7m people worldwide and over 9,000 people in Ireland.

COVID-19 moved marts online and changed farming dramatically.

People were plunged into national and regional lockdowns aimed at reducing the spread and “flattening the curve” of the disease.

The toll on mental health for people and families affected is still being counted.

In a farming context, the pandemic rules turned everything upside down.

Even today the news pages of the publication are digitally delivered from Belmullet, Co Mayo

While farmers were considered essential workers and so less restricted than most, all farming business and social outlets were changed.

Marts moved online, co-ops switched to click and collect, pubs closed, and GAA matches and almost everything else was cancelled in lockdown.

Inside the Irish Farmers Journal, remote working became the norm overnight and even today the news pages of the publication are digitally delivered to the printers from Belmullet, Co Mayo, rather than the Irish Farm Centre in Dublin.

SHARING OPTIONS