For a few hours on Monday, it looked like a deal was arrived at between the EU and UK on the issue of the Irish border. This was the third precondition for the EU, along with citizens rights and Brexit bill, that had to be resolved before negotiations could proceed to the second phase that would discuss a future trading relationship between the UK and EU after the UK’s departure.

The proposed deal was endorsed by the Irish Government, but it emerged while the the Prime Minister was in Brussels to sign it off, that it was not satisfactory to Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist party (DUP).

Their 10 MPs have a confidence and supply arrangement with the governing Conservative party in Westminster, and following a call to the Prime Minster in Brussels, the deal was off.

The DUP position was blunt – they would not accept Northern Ireland leaving the EU on different terms from the rest of the UK. It is understood the proposed deal made provision for “regulatory alignment” between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland in the event that a wider deal wasn’t reached in the negotiations between the UK and EU.

What would this deal have meant?

A deal that takes care of north-south trade is fine for farmers exporting pigs north for processing in the Karro factory in Cookstown. It would also benefit cattle coming out of marts in the west of Ireland for further feeding and processing in the north as well as carcase beef from abattoirs that is processed in the north.

It would have worked for the 400,000-plus lambs, almost half of Northern Ireland’s production, that go south for processing and onward trade to Britain and the continent and would have facilitated the trade in milk that is collected from Northern Ireland farms for creameries in the south. This is over a third of all milk that is produced in the north.

Would it have solved the Brexit problem?

The short answer is no – the most important trade for agricultural produce for both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland is with Britain. Therefore, as well as the well-reported political difficulties for the DUP in accepting an Irish Sea border, it equally didn’t work for trade.

If Northern Ireland had a different arrangement with the EU than the rest of the UK, it would be frustrating the 75% of their trade in agri food that is conducted with the rest of the UK. In addition, trade with Northern Ireland is a very small part of agri-food exports from the Republic of Ireland. Irish beef exports to Britain account for half of all production, approximately 250,000t annually.

Similarly, with cheddar cheese, 80,000t, two-thirds of production, is exported to Britain from the Republic of Ireland. Therefore, the entire island of Ireland benefits more from east-west trade than it does from north-south.

As an industry spokesman said last week, the industry doesn’t want any of these borders.

What is the best outcome for farmers?

It was notable when it looked like a deal might be in place making a special regulatory arrangement for the Irish border, that Scotland, Wales and the city of London quickly wanted the same.

That suggests that there may be a mood in the wider UK that would see a customs alignment with the EU as a feasible option that would facilitate trade with the EU post-Brexit. The trade-off would be some curtailment of the UK’s ability to do separate trade deals, at least on any product category that was covered by “regulatory alignment”.

If this outcome was agreed, it would solve the north-south and east-west trading arrangement post-Brexit and maintain trade in whatever goods were covered by the arrangement between Britain and the rest of the EU as well.

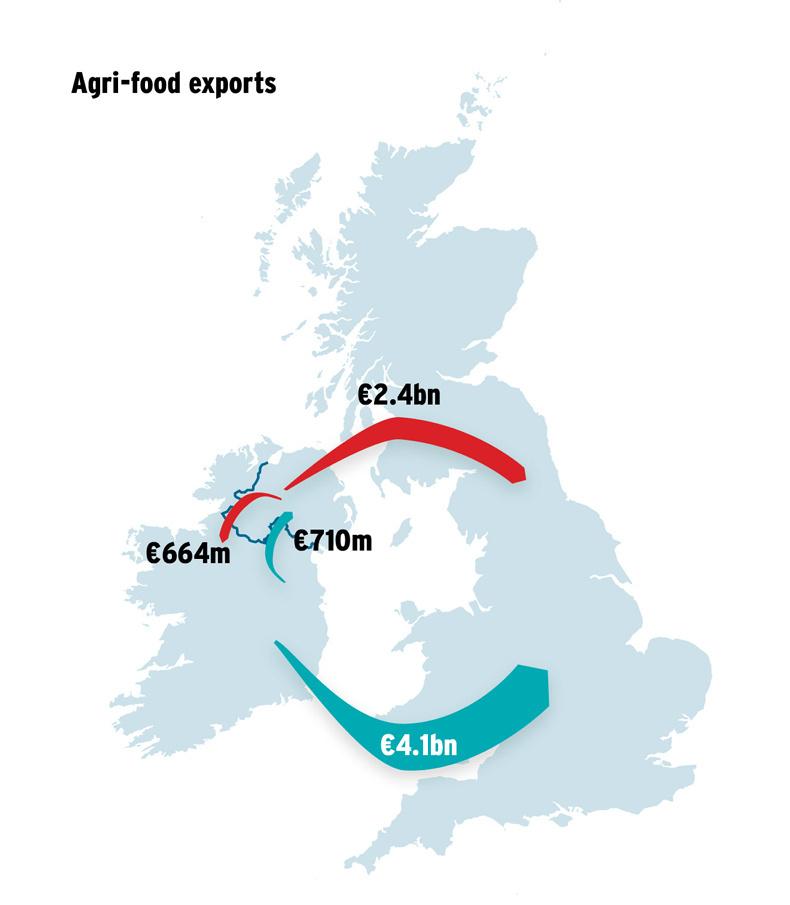

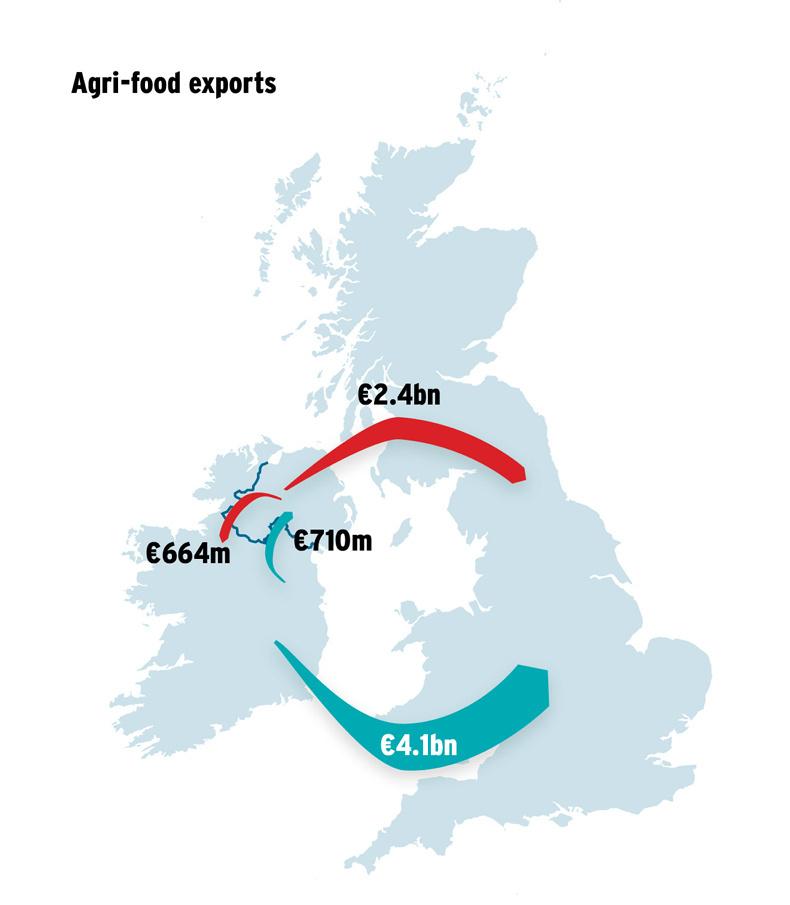

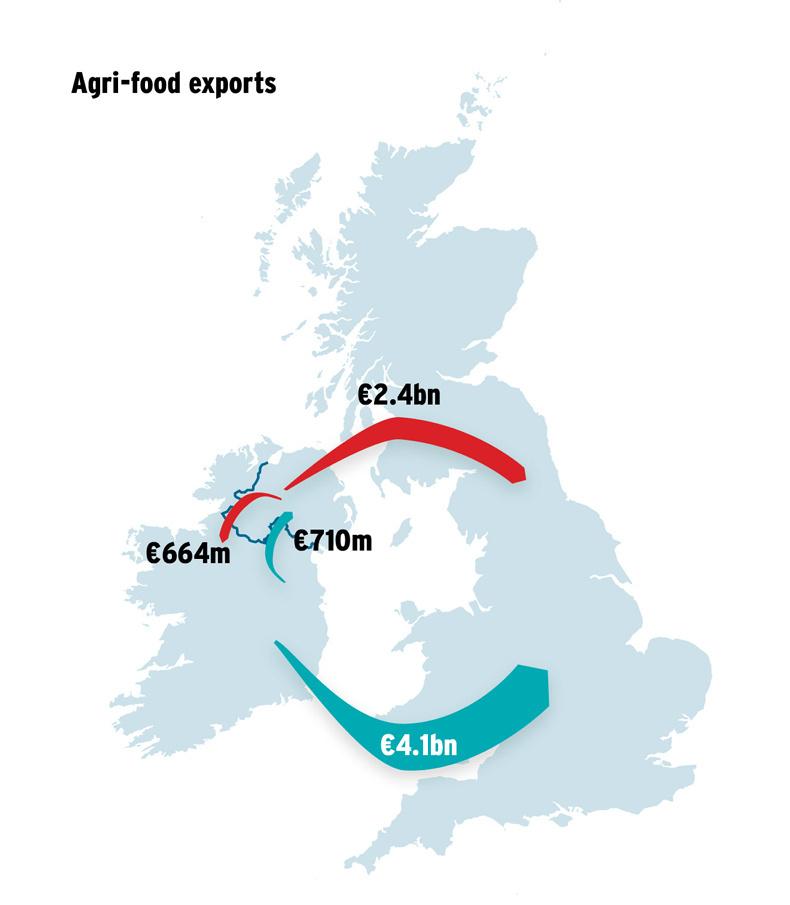

Agri food exports 2016 – Republic of Ireland to Britain – €4.1bn (£3.6bn).Republic of Ireland to Northern Ireland – €664m (£584m).(DAFM / CSO)

2015 Northern Ireland to Britain – €2.4bn (£2.1bn).Northern Ireland to Republic of Ireland – €710m (£625m).(DEARA)

For a few hours on Monday, it looked like a deal was arrived at between the EU and UK on the issue of the Irish border. This was the third precondition for the EU, along with citizens rights and Brexit bill, that had to be resolved before negotiations could proceed to the second phase that would discuss a future trading relationship between the UK and EU after the UK’s departure.

The proposed deal was endorsed by the Irish Government, but it emerged while the the Prime Minister was in Brussels to sign it off, that it was not satisfactory to Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist party (DUP).

Their 10 MPs have a confidence and supply arrangement with the governing Conservative party in Westminster, and following a call to the Prime Minster in Brussels, the deal was off.

The DUP position was blunt – they would not accept Northern Ireland leaving the EU on different terms from the rest of the UK. It is understood the proposed deal made provision for “regulatory alignment” between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland in the event that a wider deal wasn’t reached in the negotiations between the UK and EU.

What would this deal have meant?

A deal that takes care of north-south trade is fine for farmers exporting pigs north for processing in the Karro factory in Cookstown. It would also benefit cattle coming out of marts in the west of Ireland for further feeding and processing in the north as well as carcase beef from abattoirs that is processed in the north.

It would have worked for the 400,000-plus lambs, almost half of Northern Ireland’s production, that go south for processing and onward trade to Britain and the continent and would have facilitated the trade in milk that is collected from Northern Ireland farms for creameries in the south. This is over a third of all milk that is produced in the north.

Would it have solved the Brexit problem?

The short answer is no – the most important trade for agricultural produce for both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland is with Britain. Therefore, as well as the well-reported political difficulties for the DUP in accepting an Irish Sea border, it equally didn’t work for trade.

If Northern Ireland had a different arrangement with the EU than the rest of the UK, it would be frustrating the 75% of their trade in agri food that is conducted with the rest of the UK. In addition, trade with Northern Ireland is a very small part of agri-food exports from the Republic of Ireland. Irish beef exports to Britain account for half of all production, approximately 250,000t annually.

Similarly, with cheddar cheese, 80,000t, two-thirds of production, is exported to Britain from the Republic of Ireland. Therefore, the entire island of Ireland benefits more from east-west trade than it does from north-south.

As an industry spokesman said last week, the industry doesn’t want any of these borders.

What is the best outcome for farmers?

It was notable when it looked like a deal might be in place making a special regulatory arrangement for the Irish border, that Scotland, Wales and the city of London quickly wanted the same.

That suggests that there may be a mood in the wider UK that would see a customs alignment with the EU as a feasible option that would facilitate trade with the EU post-Brexit. The trade-off would be some curtailment of the UK’s ability to do separate trade deals, at least on any product category that was covered by “regulatory alignment”.

If this outcome was agreed, it would solve the north-south and east-west trading arrangement post-Brexit and maintain trade in whatever goods were covered by the arrangement between Britain and the rest of the EU as well.

Agri food exports 2016 – Republic of Ireland to Britain – €4.1bn (£3.6bn).Republic of Ireland to Northern Ireland – €664m (£584m).(DAFM / CSO)

2015 Northern Ireland to Britain – €2.4bn (£2.1bn).Northern Ireland to Republic of Ireland – €710m (£625m).(DEARA)

SHARING OPTIONS