Ireland will face enormous fines from the European Union as early as 2030 if it fails to meet targets for cutting carbon emissions.

According to the Climate Change Advisory Council’s report released on 18 October, the figure will be in the order of €8bn. This arises from the EU’s Effort Sharing Regulation, designed to cut EU emissions by 40% from the 2005 figure.

The EU has allocated non-uniform emissions reduction targets to each member state, with more demanding targets for states deemed more prosperous, and the states have translated the national targets into sector-by-sector figures. This has implied a demanding target for Ireland which is unlikely to be attained.

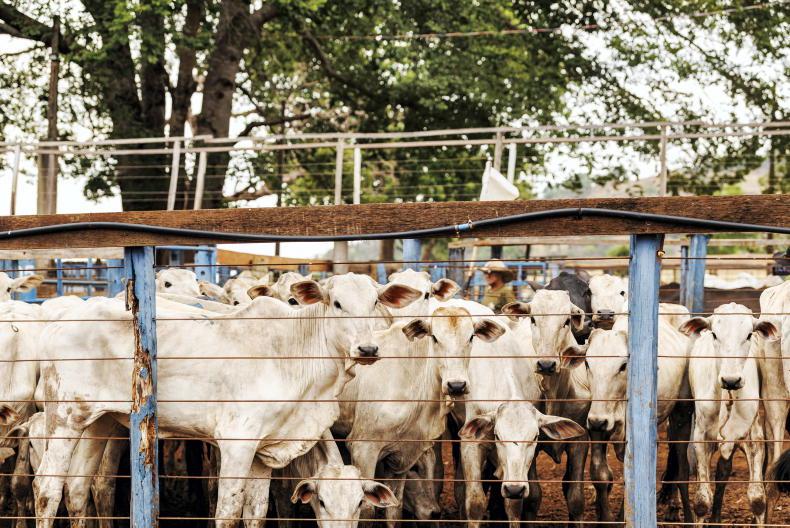

A high emissions figure is attributed to agriculture and implies a challenging target for reduction.

Emissions are measured partly on a production basis rather than on consumption and Ireland is a large net exporter of food products, including beef and dairy.

Countries which exceed the EU target can notionally purchase the missing carbon reductions from any members which over-achieve, so there would be a cheque issued from the national treasury destined for the coffers of another member state, or several.

Since governments do not provide for contingent liabilities in their budget accounts, a country in deficit, as Ireland is almost certain to be, would have to announce tax increases as 2030 approaches, and the beneficiary countries would be able to declare corresponding reductions.

This is hardly a formula for European solidarity and a potentially serious issue for Ireland given the amounts involved, not far short of the Apple corporation tax bonanza. A fair share of the Apple loot is spoken for if the EU fines ever materialise.

Whether they materialise as envisaged in the Effort Sharing Regulation is not written in stone.

Environmental agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Ireland take comfort from the EU policy ostensibly in place, referring to the various carbon reduction targets as “legally binding”.

Public spending

Indeed they contend that greater public spending should be undertaken to encourage reduced emissions in the here and now, since €8bn or some similar figure will have to be spent anyway a few years hence.

On this reasoning, a few billion upfront on schemes like home insulation looks like a bargain if a greater fine to the EU can thereby be avoided.

It all depends on whether you really believe that the 2030 targets will be met, and that the EU will follow through and impose the fines if they are not.

The Brussels-based thinktank Transport and Environment has been keeping the score and its most recent assessment for the EU’s 27 members is as follows:

Meeting 2030 target on current plans: six.Uncertain – might miss: nine.Likely to come up short: 12.Almost half of the member states will miss the target and it could be more. The aggregate shortfall is large enough to trigger the penalties in the regulation but the snag is that the countries likely to come up short include EU members which, on past form, will call the shots when it comes to real-world consequences.

Readers may recall that, prior to the 2008 financial crisis, there were EU rules about avoiding budget deficits.

One of the countries in breach happened to be Germany and the rules were quietly ignored, only to be remembered when less pivotal countries breached the limit.

One of the beneficiary countries, if Ireland has fines to pay, would be Spain, likely to undershoot its targets according to the calculations by Transport and Environment

These fiscal rules may not have made perfect sense but neither does the emissions regulation – Europe has done more already than either China or the US, the biggest absolute and relative contributors to excess planetary carbon emissions.

Moreover, one of the countries likely to be above target is Germany, and France too will struggle.

When push comes to shove, there are reasons to expect that the bill for penalties to which Ireland is exposed will never be presented.

The narrative that money may as well be spent now, since it will be forfeit to the EU in any event, does not provide a credible basis for throwing money at containing emissions. Each measure needs to be evaluated on its merits and some may be poor value in terms of reductions actually attainable.

National targets

The same concern applies to the national targets agreed at EU level and the sector-by-sector targets in each member state.

Are these the lowest-cost solution, accepting that European countries must play their part, if they result in arbitrary re-allocations of economic activity, for example from low- to high-cost producers of dairy products?

One of the beneficiary countries, if Ireland has fines to pay, would be Spain, likely to undershoot its targets according to the calculations by Transport and Environment.

If the system of emissions measurement by production, plus the prospective financial penalties, shifts dairy production away from its more natural locations, should Irish policymakers be supporting the direction of EU policy?

Ireland will face enormous fines from the European Union as early as 2030 if it fails to meet targets for cutting carbon emissions.

According to the Climate Change Advisory Council’s report released on 18 October, the figure will be in the order of €8bn. This arises from the EU’s Effort Sharing Regulation, designed to cut EU emissions by 40% from the 2005 figure.

The EU has allocated non-uniform emissions reduction targets to each member state, with more demanding targets for states deemed more prosperous, and the states have translated the national targets into sector-by-sector figures. This has implied a demanding target for Ireland which is unlikely to be attained.

A high emissions figure is attributed to agriculture and implies a challenging target for reduction.

Emissions are measured partly on a production basis rather than on consumption and Ireland is a large net exporter of food products, including beef and dairy.

Countries which exceed the EU target can notionally purchase the missing carbon reductions from any members which over-achieve, so there would be a cheque issued from the national treasury destined for the coffers of another member state, or several.

Since governments do not provide for contingent liabilities in their budget accounts, a country in deficit, as Ireland is almost certain to be, would have to announce tax increases as 2030 approaches, and the beneficiary countries would be able to declare corresponding reductions.

This is hardly a formula for European solidarity and a potentially serious issue for Ireland given the amounts involved, not far short of the Apple corporation tax bonanza. A fair share of the Apple loot is spoken for if the EU fines ever materialise.

Whether they materialise as envisaged in the Effort Sharing Regulation is not written in stone.

Environmental agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Ireland take comfort from the EU policy ostensibly in place, referring to the various carbon reduction targets as “legally binding”.

Public spending

Indeed they contend that greater public spending should be undertaken to encourage reduced emissions in the here and now, since €8bn or some similar figure will have to be spent anyway a few years hence.

On this reasoning, a few billion upfront on schemes like home insulation looks like a bargain if a greater fine to the EU can thereby be avoided.

It all depends on whether you really believe that the 2030 targets will be met, and that the EU will follow through and impose the fines if they are not.

The Brussels-based thinktank Transport and Environment has been keeping the score and its most recent assessment for the EU’s 27 members is as follows:

Meeting 2030 target on current plans: six.Uncertain – might miss: nine.Likely to come up short: 12.Almost half of the member states will miss the target and it could be more. The aggregate shortfall is large enough to trigger the penalties in the regulation but the snag is that the countries likely to come up short include EU members which, on past form, will call the shots when it comes to real-world consequences.

Readers may recall that, prior to the 2008 financial crisis, there were EU rules about avoiding budget deficits.

One of the countries in breach happened to be Germany and the rules were quietly ignored, only to be remembered when less pivotal countries breached the limit.

One of the beneficiary countries, if Ireland has fines to pay, would be Spain, likely to undershoot its targets according to the calculations by Transport and Environment

These fiscal rules may not have made perfect sense but neither does the emissions regulation – Europe has done more already than either China or the US, the biggest absolute and relative contributors to excess planetary carbon emissions.

Moreover, one of the countries likely to be above target is Germany, and France too will struggle.

When push comes to shove, there are reasons to expect that the bill for penalties to which Ireland is exposed will never be presented.

The narrative that money may as well be spent now, since it will be forfeit to the EU in any event, does not provide a credible basis for throwing money at containing emissions. Each measure needs to be evaluated on its merits and some may be poor value in terms of reductions actually attainable.

National targets

The same concern applies to the national targets agreed at EU level and the sector-by-sector targets in each member state.

Are these the lowest-cost solution, accepting that European countries must play their part, if they result in arbitrary re-allocations of economic activity, for example from low- to high-cost producers of dairy products?

One of the beneficiary countries, if Ireland has fines to pay, would be Spain, likely to undershoot its targets according to the calculations by Transport and Environment.

If the system of emissions measurement by production, plus the prospective financial penalties, shifts dairy production away from its more natural locations, should Irish policymakers be supporting the direction of EU policy?

SHARING OPTIONS