The gravity of the blackgrass resistance challenge in the UK can sometimes go under the radar here in Ireland. On recent trips to various trade shows and conferences in England , this was one topic which was hard to get away from.

You would be forgiven for thinking that nearly every facet of crop planning and husbandry revolves around the management and eradication of the weed.

Blackgrass was always present in the UK and used to be a manageable weed. In 1989, blackgrass was rated the eight most frequent weed.

Through a combination of factors, including increased winter cereal production, narrower rotations, earlier planting, a move away from plough based systems and over-reliance on chemical control, the evolution of herbicide resistance was rapid.

This has now allowed the weed to claim top place as the UK tillage industry’s number one weed. It doesn’t get its nickname ‘the farm killer’ for nothing.

While conventional methods of weed control may, for now, be effective against many weed groups, blackgrass is different.

The weed is particularly prone to the development of resistance, explains Paul Neve of Rothamsted Research.

Herbicide resistance is inherited and occurs through selection of plants that survive herbicide treatment.

With repeated selection, resistant plants multiply to dominate the population. With blackgrass capable of producing up to 6,000 viable seeds per plant, it’s easy to see how resistant strains can multiply.

Understanding the evolution of this resistance, and devising ways in which it could have been prevented, or at least delayed, seems easy with hindsight.

The questions is: can lessons be learned from the evolution of blackgrass resistance to help prevent resistance development in other herbicide groups, such as glyphosate?

Blackgrass Resistance Initiative

The distribution and abundance of resistant blackgrass continues to spread in the UK, namely England.

This was explained by Paul as he presented the findings of a four-year Blackgrass Resistance Initiative (BGRI) at the recent AHDB agronomy conference.

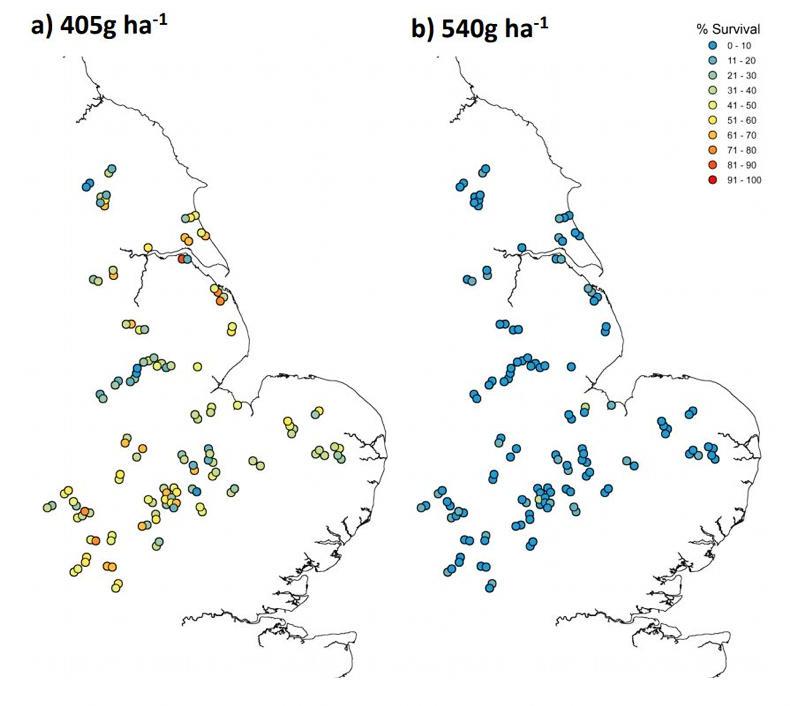

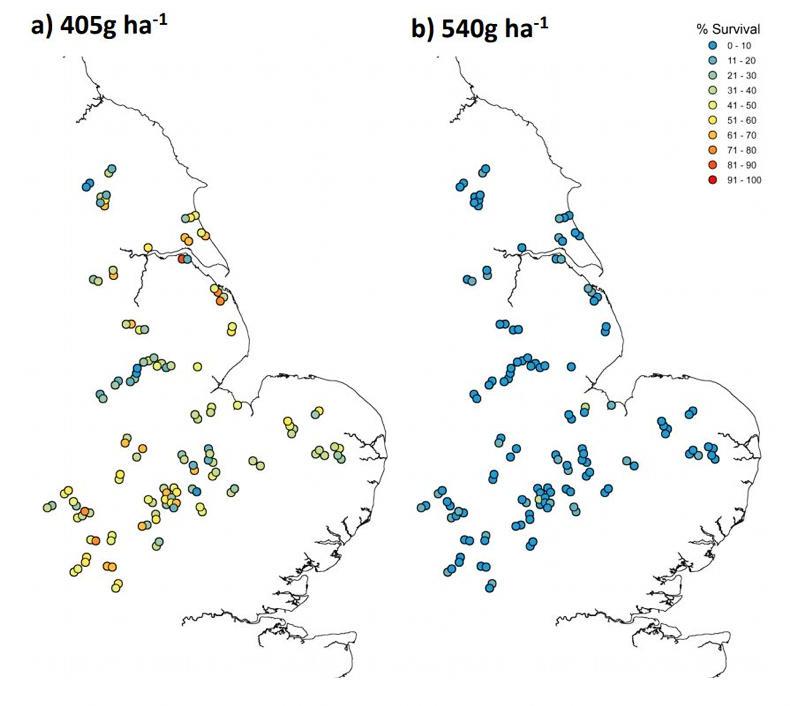

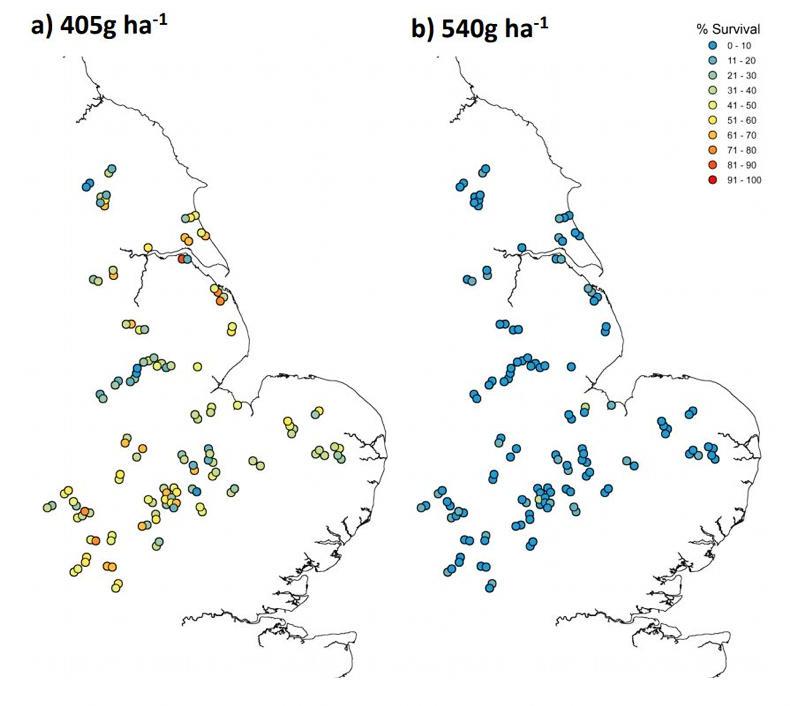

Through developing a network of 71 farms across the UK, they were able to monitor blackgrass populations throughout the four years, track their abundance and spread and monitor population resistance.

A graph showing the current glyphosate sensitivity of Blackgrass populations at full rate vs three quarter rate.

The project also focused on growers’ historical management over the previous 10 years to help identify management practices that appeared to lead to the evolution of resistance across these farms.

Over the course of the four years, around 30,000 plants were tested for resistance against full rates of three common post emergent herbicides.

He explains that, on average, the test populations were 75% resistant to Atlantis (mesosulfuron/iodosulfuron), 90% resistant to Cheetah (fenoxaprop) and 56% resistant to Laser (cycloxydim).

Drivers of resistance

Paul explains how the main driver of resistance on those 71 farms appeared to be linked to the extent of historical use of those herbicides.

In other words, the farms which had used specific herbicides over the past 10 years were more likely to have plant populations which were resistant to those herbicides.

In addition to this, historical management data showed that mixing modes of action did little to slow the build-up of resistance on those farms.

He explained that there are essentially two main types of resistance.

Target site resistance (TSR) involves single mutations or changes in the genes that the herbicides target in the weed.

TSR is a major mechanism of resistance but, based on the analysis of their populations, it alone did not fully account for the level of resistance observed.

This indicated that a second mode of resistance was present.

This second mode was non-target-site resistance (NTSR), also known as metabolic resistance. Where this occurs, weeds develop the ability to rapidly metabolise or break down the herbicide before it can cause a significant affect on the weed.

Based on their analysis of the farms where plant populations displayed TSR only, mixing of herbicide groups was shown to help prevent development of resistance.

However, where mixed herbicide groups were used to create a diversity of actives, this appears to have led to higher levels of NTSR.

So it seems that mixed herbicide groups facilitated the development of resistance to the herbicides used.

Overall, based on their findings, Paul explained that herbicide diversity alone does not appear to slow evolution of resistance in blackgrass due to the prominence of NTSR.

Pre-emptive resistance management: glyphosate

Now that we know the causes of blackgrass resistance, can we use this information to prevent the development of resistance to the most widely used herbicide in Ireland and the UK?

Yes is the answer, according to Paul and his findings say that this is essential.

At three quarter field rates, only 50-60% blackgrass control was achieved using glyphosate.

Since 1990 there has been an eight-fold increase in the use of glyphosate globally.

There are around 45 known species of weeds which have developed resistance to glyphosate but none are present in Ireland or the UK.

From samples collected on the monitor farms, the researchers conducted a number of dose response experiments on blackgrass populations to determine their sensitivity to glyphosate.

At 1.5 l/ha (360 g/l product ) they got very good control.

However, at 1.125 l/ha they only achieved 50-60% control in many of the samples tested (see graph).

The management history of the fields showed that reduced sensitivity occurred where glyphosate was used more frequently over the past 10 years.

This also showed that reduced sensitivity did not occur in fields where glyphosate was used less frequently.

Paul concluded by saying that it is possible for blackgrass populations to develop further reduced sensitivity to glyphosate if its use is not managed correctly.

If this applies to blackgrass, then it is possible that the same principle can apply to other grassweed species.

Proactive approach

For this reason it is important to take a proactive approach when dealing with weeds. While there are no known cases of outright resistance to glyphosate in major weed groups in Irish and UK fields, this may not stay this way for ever.

The tight densely packed head of Blackgrass can produce up to 6,000 weeds.

The need to develop an integrated weed management approach was one of Paul’s concluding remarks.

This means that one single method of weed control alone will never be the answer.

For example, in Table 1 the various methods of non-chemical control of blackgrass are listed, as is their average control levels.

This work was carried out by the AHDB in 2013. Take ploughing for example, the average level of control is 69%.

But look at the variation in control, it ranges from -82% to 96%. That means that on one of the AHDB trial sites, ploughing made the problem 82% worse.

There’s no one silver bullet and effective control encompasses a combination of cultural and chemical means.

We in Ireland must learn from the blackgrass resistance situation in the UK. While glyphosate remains effective for now, nature has a habit of evolving.

Read more

Watch: farmers protest over low vegetable prices in Dublin

Listen: sugar beet co-op plan draws in tillage growers

The gravity of the blackgrass resistance challenge in the UK can sometimes go under the radar here in Ireland. On recent trips to various trade shows and conferences in England , this was one topic which was hard to get away from.

You would be forgiven for thinking that nearly every facet of crop planning and husbandry revolves around the management and eradication of the weed.

Blackgrass was always present in the UK and used to be a manageable weed. In 1989, blackgrass was rated the eight most frequent weed.

Through a combination of factors, including increased winter cereal production, narrower rotations, earlier planting, a move away from plough based systems and over-reliance on chemical control, the evolution of herbicide resistance was rapid.

This has now allowed the weed to claim top place as the UK tillage industry’s number one weed. It doesn’t get its nickname ‘the farm killer’ for nothing.

While conventional methods of weed control may, for now, be effective against many weed groups, blackgrass is different.

The weed is particularly prone to the development of resistance, explains Paul Neve of Rothamsted Research.

Herbicide resistance is inherited and occurs through selection of plants that survive herbicide treatment.

With repeated selection, resistant plants multiply to dominate the population. With blackgrass capable of producing up to 6,000 viable seeds per plant, it’s easy to see how resistant strains can multiply.

Understanding the evolution of this resistance, and devising ways in which it could have been prevented, or at least delayed, seems easy with hindsight.

The questions is: can lessons be learned from the evolution of blackgrass resistance to help prevent resistance development in other herbicide groups, such as glyphosate?

Blackgrass Resistance Initiative

The distribution and abundance of resistant blackgrass continues to spread in the UK, namely England.

This was explained by Paul as he presented the findings of a four-year Blackgrass Resistance Initiative (BGRI) at the recent AHDB agronomy conference.

Through developing a network of 71 farms across the UK, they were able to monitor blackgrass populations throughout the four years, track their abundance and spread and monitor population resistance.

A graph showing the current glyphosate sensitivity of Blackgrass populations at full rate vs three quarter rate.

The project also focused on growers’ historical management over the previous 10 years to help identify management practices that appeared to lead to the evolution of resistance across these farms.

Over the course of the four years, around 30,000 plants were tested for resistance against full rates of three common post emergent herbicides.

He explains that, on average, the test populations were 75% resistant to Atlantis (mesosulfuron/iodosulfuron), 90% resistant to Cheetah (fenoxaprop) and 56% resistant to Laser (cycloxydim).

Drivers of resistance

Paul explains how the main driver of resistance on those 71 farms appeared to be linked to the extent of historical use of those herbicides.

In other words, the farms which had used specific herbicides over the past 10 years were more likely to have plant populations which were resistant to those herbicides.

In addition to this, historical management data showed that mixing modes of action did little to slow the build-up of resistance on those farms.

He explained that there are essentially two main types of resistance.

Target site resistance (TSR) involves single mutations or changes in the genes that the herbicides target in the weed.

TSR is a major mechanism of resistance but, based on the analysis of their populations, it alone did not fully account for the level of resistance observed.

This indicated that a second mode of resistance was present.

This second mode was non-target-site resistance (NTSR), also known as metabolic resistance. Where this occurs, weeds develop the ability to rapidly metabolise or break down the herbicide before it can cause a significant affect on the weed.

Based on their analysis of the farms where plant populations displayed TSR only, mixing of herbicide groups was shown to help prevent development of resistance.

However, where mixed herbicide groups were used to create a diversity of actives, this appears to have led to higher levels of NTSR.

So it seems that mixed herbicide groups facilitated the development of resistance to the herbicides used.

Overall, based on their findings, Paul explained that herbicide diversity alone does not appear to slow evolution of resistance in blackgrass due to the prominence of NTSR.

Pre-emptive resistance management: glyphosate

Now that we know the causes of blackgrass resistance, can we use this information to prevent the development of resistance to the most widely used herbicide in Ireland and the UK?

Yes is the answer, according to Paul and his findings say that this is essential.

At three quarter field rates, only 50-60% blackgrass control was achieved using glyphosate.

Since 1990 there has been an eight-fold increase in the use of glyphosate globally.

There are around 45 known species of weeds which have developed resistance to glyphosate but none are present in Ireland or the UK.

From samples collected on the monitor farms, the researchers conducted a number of dose response experiments on blackgrass populations to determine their sensitivity to glyphosate.

At 1.5 l/ha (360 g/l product ) they got very good control.

However, at 1.125 l/ha they only achieved 50-60% control in many of the samples tested (see graph).

The management history of the fields showed that reduced sensitivity occurred where glyphosate was used more frequently over the past 10 years.

This also showed that reduced sensitivity did not occur in fields where glyphosate was used less frequently.

Paul concluded by saying that it is possible for blackgrass populations to develop further reduced sensitivity to glyphosate if its use is not managed correctly.

If this applies to blackgrass, then it is possible that the same principle can apply to other grassweed species.

Proactive approach

For this reason it is important to take a proactive approach when dealing with weeds. While there are no known cases of outright resistance to glyphosate in major weed groups in Irish and UK fields, this may not stay this way for ever.

The tight densely packed head of Blackgrass can produce up to 6,000 weeds.

The need to develop an integrated weed management approach was one of Paul’s concluding remarks.

This means that one single method of weed control alone will never be the answer.

For example, in Table 1 the various methods of non-chemical control of blackgrass are listed, as is their average control levels.

This work was carried out by the AHDB in 2013. Take ploughing for example, the average level of control is 69%.

But look at the variation in control, it ranges from -82% to 96%. That means that on one of the AHDB trial sites, ploughing made the problem 82% worse.

There’s no one silver bullet and effective control encompasses a combination of cultural and chemical means.

We in Ireland must learn from the blackgrass resistance situation in the UK. While glyphosate remains effective for now, nature has a habit of evolving.

Read more

Watch: farmers protest over low vegetable prices in Dublin

Listen: sugar beet co-op plan draws in tillage growers

SHARING OPTIONS